Special Release: Deviations from the Norm

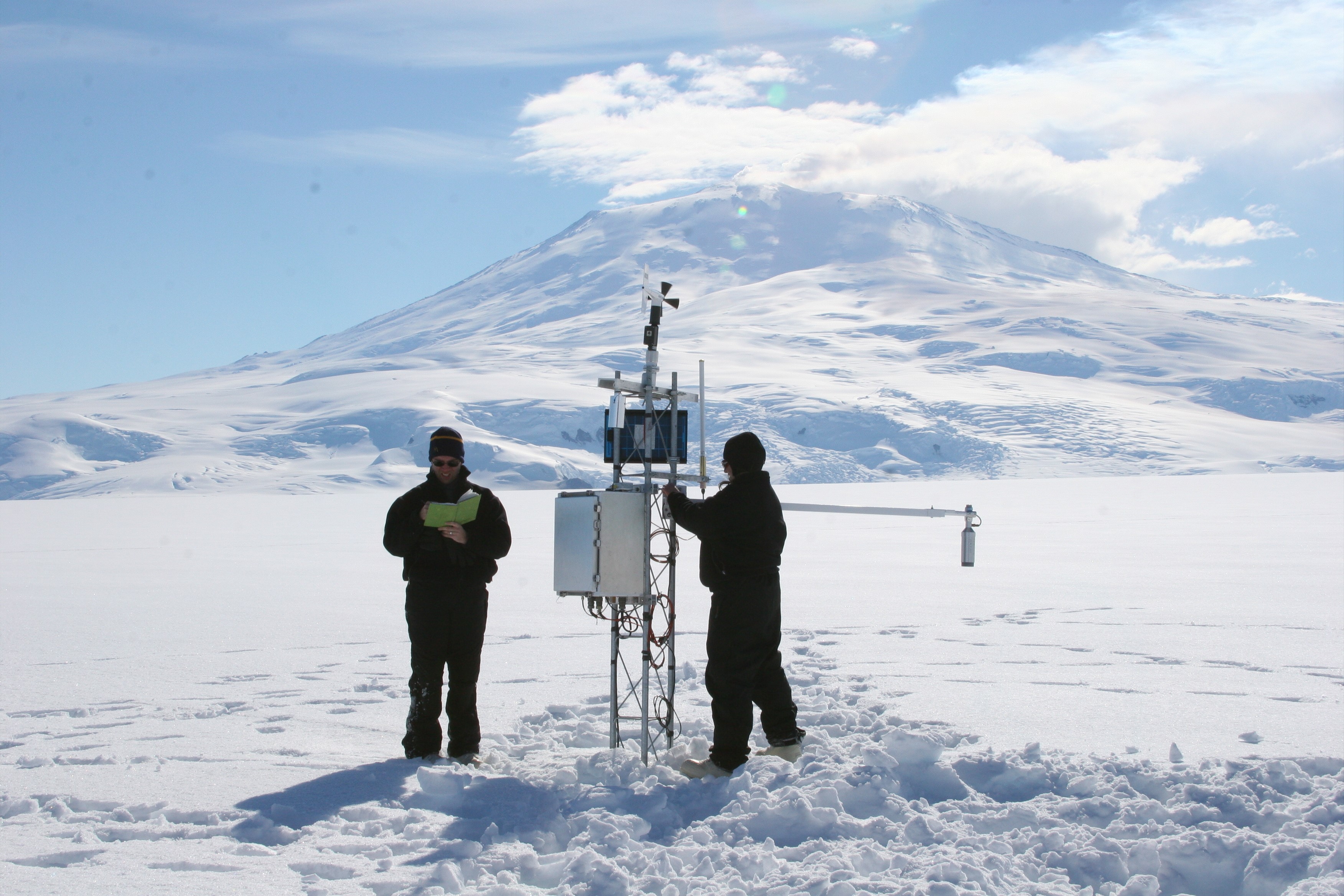

Ryan Fogt (left) and colleague Shelley Knuth (right) installing a new sensor on a weather tower on the Ross Ice Shelf, near McMurdo Station Antarctica. Photo credit: Ryan Fogt

One of the most alluring parts of Earth and space science is that much of the key research takes place in the field, in some of the most incredible – and inhospitable – environments on the planet: on treacherous polar ice sheets, aboard sea tossed ships, at the mouths of active volcanoes, beneath turbid ocean waters, and atop the highest windswept peaks. Under these often less than ideal conditions, instruments often fail, the weather can become uncooperative, and the best made scientific plans are undone.

In this special episode of Third Pod from the Sun, five scientists share their stories of “deviations from the norm” – when their fieldwork went awry on the account of everything from uncooperative arctic mollusks, inaccessible food supplies buried in snows of Greenland, overfilled stoves and flammable tents, wayward Turkish donkeys, and inoperative rifles in polar bear country. Mishaps, however, can sometimes lead to some surprising and unexpected insights.

This episode was produced by Joshua Speiser and mixed by Kayla Surrey.

Transcript

Shane Hanlon: Hi, Nanci.

Nanci Bompey: Hey, Shane. So you were just out in the field.

Shane Hanlon: I was. I was just out in the field. I was teaching in the field.

Nanci Bompey: Teaching in the field. So that leads us to the question.

Shane Hanlon: The question.

Nanci Bompey: I’m not going to call them failures, but when things didn’t go quite right for you in the field, how many of those have you encountered over your career as a scientist?

Shane Hanlon: Like when I was a researcher?

Nanci Bompey: Yes.

Shane Hanlon: I don’t think that that ever actually happened.

Nanci Bompey: Oh, oh. I guess you’re perfect.

Shane Hanlon: No, no. Let’s say I was incredibly fortunate that I reached low, and it was a-

Nanci Bompey: That’s a good way. That’s good.

Josh Speiser: Aim low.

Nanci Bompey: That’s also good.

Shane Hanlon: Yeah, yeah, so it worked out fine. What about you? You used to be a scientist.

Nanci Bompey: I had lots of failures. Perhaps that’s why I became a journalist.

Shane Hanlon: Right.

Nanci Bompey: Yeah.

Shane Hanlon: Anything exciting, or-

Nanci Bompey: I feel like this isn’t really a failure. I feel like we just didn’t know what we were doing when we were undergraduates in the lab.

Shane Hanlon: That sounds right.

Nanci Bompey: Yeah.

Shane Hanlon: I feel like that’s most undergrads, I guess.

Nanci Bompey: That’s probably most undergrads.

Shane Hanlon: That’s how I was.

Nanci Bompey: I’m sure there were times when I feel like there was actual mercury not contained somewhere in the lab-

Shane Hanlon: Oh.

Nanci Bompey: … and we didn’t know what to do and just put it down a drain or something.

Shane Hanlon: That is not good.

Nanci Bompey: No.

Shane Hanlon: Not good at all.

Nanci Bompey: No, no.

Shane Hanlon: So we’re talking about this because it’s that time of year where folks are out in the field or in the lab or whatever it is, and I guess we’re going to hear from some folks who will tell us about times when things didn’t quite go according to plan.

Shane Hanlon: Welcome to the American Geophysical Union’s podcast about the scientists and the methods behind the science. These are the stories you won’t read in the manuscript or hear in a lecture. I’m Shane Hanlon.

Nanci Bompey: I’m Nanci Bompey.

Shane Hanlon: This is a special edition of Third Pod from the Sun.

Shane Hanlon: All right. So we’re actually going to bring in one of our co-producers, Josh Speiser. Hi, Josh.

Josh Speiser: Hello, Shane.

Shane Hanlon: Do you want to explain what this all … What this all … What is this all about?

Josh Speiser: What is this all about? So we did some outreach to the AGU scientist community and basically asked folks for their stories about some of their mishaps or trials and travails in the field. We got a number of stories that were sent to us, and then we recorded those stories which you are now going to experience now.

Shane Hanlon: Great. All right. Well, who do we have first?

Josh Speiser: First, our first fail … Well, our first mishap comes from Christine Bassett, a PhD candidate at the University of Alabama.

Christine Bassett: My name is Christine Bassett, and I’m a PhD candidate at the University of Alabama. I use the chemistry of seashells to tell me about the environment that they were living in, what the salinity of the water was, the temperature of the water, and sometimes even the nutrient flux. In order to be able to use seashells to tell us about the past, we have to study modern species of seashells or modern species of mollusks to tell us a little bit about the relationship between the chemistry in their shells and the chemistry and the temperature of the water that they’re growing in.

We collect live specimens of different species of mollusks so we can do a chemical analysis of those shells. In my work in the Aleutian Islands, that has involved scuba diving and digging into the sediments to be able to find where those shells are. That might sound a little bit easy, but if you’ve ever gone clamming before on the beach, it’s not easy on land and it’s even harder underwater.

So my dive buddy and I, who works for Alaska Sea Grant, we devised a method where we would rig up this PVC pipe to a scuba tank. We were going to run it in reverse like you do with your vacuum cleaner, but it was going to suck out the sediments. That way, we can quickly dig down into the sand to find the clams and put them in our bag.

We thought that was a fantastic idea, but what had happened … You would think scuba divers would know this, but what had happened was it sucked up all the sediment like we wanted it to, but then the sediment just fell right back down on top of us. We couldn’t see anything. We were diving in basically zero visibility and decided that that was not a good idea. Let’s call the dive and try again.

That was a massive fail, and we were pretty disappointed because we spent months planning out how to rig this thing up to the scuba tank. There you are in the middle of the Aleutian Islands, and there’s only so much troubleshooting you can do because there’s not a Home Depot right down the road to help you out. They do have some shipping supply stores and some basic supplies.

So we ended up and buying just a hand rake for a garden and a hand shovel. We took that and tied it to a neon yellow line so we wouldn’t lose it and tied it to our scuba suits, and we went and started raking away at the sediments to try and find them then.

We did find them. We were somewhat successful. If you’ve ever scuba dived underwater, the way that you can find mollusks, especially the kind that like to

burrow, is by seeing their little siphons sticking out of the sediments. We would look for these siphons, and we’d find them, and we’d grab it and then hold onto the siphon while we dig away with the hand rake. But these things burrow really quickly and ferociously, so what happened is their little siphons would just pop off. It was sad for both the clam and for us as well. That was also less successful because we were not fast enough at raking away the sediments as they were burrowing.

What we ultimately ended up doing is just using the ecology around us to help us figure out where they were. It turns out that there’s a type of sea star called a pycnopodia sea star. They’re those massive purple sea stars that have … I think it’s 16 legs. I’m not a biologist. Don’t quote me on that. But 16 legs, and what they do is they extend their stomachs to eat these clams. They’re really efficient at digging down into the sediments and finding them and pulling them out. When they extend their stomachs to eat those clams, they bulge up in a way that’s pretty easy to notice.

So at the end of the day, our most successful strategy was looking for all of the pycnopodia sea stars we could find that were bulging up, flipping them over to see what they were eating, and if they had the clam we were looking for, we’d steal their dinner and put it away in our bag, and turn them back over and send them on their way.

Nanci Bompey: Oh, so they looked for the sea stars to find the clams.

Shane Hanlon: They did. I know.

Nanci Bompey: That’s pretty smart.

Shane Hanlon: That’s pretty good ingenuity. I appreciate that as an ecologist.

Shane Hanlon: All right. Our next story comes from Ryan Fogt, an associate professor in the department of geography at Ohio University.

Ryan Fogt: Yeah, I’m Ryan Fogt. I’m an associate professor here in the department of geography at Ohio University. I teach meteorology classes here at Ohio University, and then I also do research on Antarctic climate variability.

You go through a survival training class where you camp out overnight on the Ross Ice Shelf. You build a little igloo and learn how to make blocks and protect yourself from weather, how to put a stove together and make fires, and pitch a tent, collect waste because waste is collected on the continent. It’s not left on the continent.

Yeah, you go through this exercise where you try to do a rescue for a comrade who’s lost in the snow storm. It’s a fun exercise where you put these white buckets on over your head. You’re in a snow-blindness scenario where you can’t

see because of this blowing snow or just whatever, and you have one colleague that you’re trying to find. You have to develop a strategy with your team to find that lost colleague. I think it’d be fun to be that person. I’ve never actually been the person that’s lost because you can see the whole team trying to find you with buckets on their head.

Ultimately, our team on my day did not find the colleague. I think we would have if we were given more time, but they cut us off after a bit of time, probably because we were doing the wrong thing or going in the wrong direction. But then we debriefed about what we did wrong and what the ultimate strategy is to find people so that you can learn from this in case a situation would happen when you’re out in the field.

We were trying to take a rope and do concentric circles from a fixed point out from that rope.

Nanci Bompey: Oh.

Ryan Fogt: Which I think is the right strategy because you won’t walk over your path more than once, essentially, but what was happening was that we were not walking uniformly. People were walking faster than other people, and so we ended up not doing concentric circles but more rather jagged paths that were crossing each other and colliding with each other somehow.

Even though we were all holding onto one rope, because we were disoriented so badly, we ended up going in the wrong direction. I remember falling down several times, actually. Just small little changes in the elevation of the snow would cause me to just trip and fall, and then I’d stand up and I wouldn’t be pointing in the right direction when I stood. I think the right strategy is these concentric circles from a fixed point so that you’re continually expanding your search area with keeping a bearing at a fixed location, but we were not successfully doing that.

I have so many fond memories of that snow school. Just the people, hanging out with them, just talking and getting to know other people and some of the failures that we had in what we were supposed to be doing that we didn’t do quite successfully.

Another one was lighting the stove. None of us had actually camped where we had a stove for whatever reason, and so our first experience with this was in Antarctica. We were filling the oil into the stove, and we spilled a bit of it. We thought, “Oh, it’ll just evaporate away. No problem.” We go to strike the match-

Nanci Bompey: Oh no.

Ryan Fogt: … to light the stove, and apparently, we had spilled a lot more than we had because the bottom of our tent immediately caught on fire. We’re all in a

panicked state of shock like, “Oh my gosh, the tent’s on fire. What do we do?” We’re all just watching it in disbelief that it’s on fire. What’s really funny is we had even a firefighter out with us, one of the [inaudible 00:10:58] firefighters doing the snow school with us, and he also was like, “Whoa.”

Yeah, and we tried to pour water on it. That was a mistake. We ended up getting it under control by blotting it, but just this idea that there’s this big fire all of a sudden that pitched in the bottom of our tent … Yeah, it was an adventure.

Shane Hanlon: When you first read snow school, it’s like, “Oh, I love winter. This sounds-“

Nanci Bompey: Oh, it sounds cool.

Shane Hanlon: I know. It sounds really exciting, and then you read or, I guess, hear the rest of this and it’s like, “Oh. There’s a lot that could go wrong.”

Nanci Bompey: Yeah, it’s hard. Snow school is hard.

Next up, we have Sandra Schumacher with the Federal Institute for Geosciences and Natural Resources in Germany, who proves that research mishaps are a universal phenomenon.

Sandra Schumacher: Well, my name is Sandra Schumacher. I work for the Federal Institute for Geosciences and Natural Resources in Germany, and right now, I do work in characterizing rocks for a potential nuclear repository. We put rocks into a triaxial apparatus, apply pressures and temperatures, and look how the rock behaves and when it fails to figure out what conditions we should avoid in a nuclear repository.

It was when I was doing my studies, and I did field work in Troy doing magnetic measurements for the archeologists there. Well, yeah, we were three students there, and we had an epic field work fail, at least from our point of view.

If you want to do magnetic measurements, you have a magnetometer in order to do the actual measurements, and you have a base station to record the diurnal variations of the magnetic field. In order to save weight and space for transport, we had a very fragile construction to mount the base station, just two meter long fiberglass poles, three ropes, and tent pegs in order to fix it.

Yeah, that worked pretty well. It always did in Germany. Then one day in Troy, we were standing there and saw a donkey coming along. We tried to shoo it away, but it didn’t work. Well, I don’t know if the donkey was just curious or wanted to scratch his back on the fiber pole, but end of story, the base station came crashing down.

We were horrified. You don’t want to crash your equipment from two meter high and down onto the ground. Yeah, it was just awful. It was awful because we were in the field. We couldn’t check if it was still working, and we were worried. Okay, if this base station is now broken the rest of the field campaign, then another two weeks of work will be futile because we don’t have the corrections we need.

Also, how do you explain this to your supervisor? “Well, the base station is broken, but it wasn’t us. It was the donkey.” Fortunately, we told him afterwards. In the evening, we checked our equipment and realized that the data were corrupt for that day but that with a little bit of fixing, we could repair the base station. Just the connections to the data log were a bit shaky. We could fix that, and we just lost one day of data but not the whole campaign. We were really, really relieved.

After some time, the donkey just left. We later learned that it’s pretty common to have free-roaming donkeys in Turkey. They can also show up on the street if you turn a corner or so. But yeah, we didn’t take this issue of free-roaming donkeys into account when we fixed our equipment and decided to have such a fragile construction.

I feel like free-ranging donkeys would be … I guess free-roaming … either, it doesn’t matter … would be a really great name for an indie band.

Nanci Bompey: Totally.

Shane Hanlon: I could just see that coming through my feed.

Nanci Bompey: Oh my God, fully.

Shane Hanlon: Free-Roaming Donkeys? Yeah.

Nanci Bompey: Would they be sort of … I don’t know.

Shane Hanlon: Electronica, maybe. Something a little whimsical.

Nanci Bompey: I love it.

Shane Hanlon: All right. Next up, we have Angela Marusiak. She is a graduate research assistant at the University of Maryland.

Angela Marusiak: My name is Angela Marusiak. I’m a graduate research assistant at the University of Maryland, and I study planetary seismology, including ocean worlds. Part of that research is going to really interesting and remote field sites.

One of the really exciting field opportunities I had was to go to the site in Northwest Greenland. Greenland is an analog for ocean worlds, which are these

icy bodies that are covered in ice and could have oceans underneath them, like Europa and Enceladus. The idea is that we can use places like Greenland that have really thick ice to test out equipment that could maybe fly on a future mission.

I was really excited to get to go out. I’d previously done some field work in Alaska on a similar project, and it went really, really well. My advisor and some of our other colleagues went out in late May and June to install our equipment, and their campaign was really successful. The installation went well. It wasn’t without hiccups, but in general, they nailed everything that they wanted to get done. They did so well, in fact, my advisor came back and said, “We got some really great data. It’d be really awesome if you could find time to do similar experiments and really hit it out of the park.” But basically, within a few days of us heading out into the field, things didn’t quite go so well.

The original plan was we could take a military plane from BWI in Baltimore right up to Thule Air Force base. Then from Thule, we would spend about two or three days there before heading into our field site to spend about two weeks there. We were going to fly out on a Wednesday, and on Monday, we got the notification that we couldn’t all fit on the military flight. We’d have to fly commercial. Okay. Cool. You have your brief moment of panic. All right, we’ve got to book new flights.

So instead of flying direct, which would have been maybe a six hour flight, we ended up having to fly to Reykjavik, Iceland, transfer airports, spend an overnight in a small village in Southwest Greenland, and then fly up to Thule the next day. Instead of six hours, it basically became a 48 hour ordeal.

We get to Thule, and we find out that odds were we weren’t going to be able to head out into the field the next day. We get to the field by flying on a helicopter. Helicopters tend to be limited by the weather more so than planes. They need to be able to see where they’re landing, and they can only fly so high, so we need to make sure that clouds are not an issue. That was one of the big limiting factors we had.

Originally, we were supposed to fly out on a Saturday, which was the 4th, and we didn’t fly out until nine days later. You can imagine if you were at an airport, and you keep hearing about your flight getting delayed an hour or two at a time. That’s the feeling you have to deal with.

Every morning, we would wake up and we’re like, “All right, today is going to be the day.” We’d go to the hanger. We would have our weather apps open, trying to figure out can we make it out today? Are we going to get stuck? Day after day, hearing, “Nope, it’s not going to happen.” You understand because it’s a safety issue. You don’t want to land if you can’t see how close you are to the ice, and safety is a priority. So we’re like, “All right, this is really annoying.” We understand, but the ninth day, we were going crazy.

It takes an emotional toll a little bit when you’re starting to get frustrated. Before we went into the field, we had an almost day to day plan. This was by no means our planner’s first experience. We had a field expert with us. But eventually, we got into the helicopter, and we’re flying out to the field site. Yay.

So three of our members had been to the site before, and then three of us were new. We were getting close to the field site, and I hear one of the [PAs 00:20:06] go, “We should be here.” We’re not seeing our equipment and arrays. We put flags in the ground, and eventually, they’re like, “Oh, well, there’s our flags. Where’s everything else?”

We land, and we realize that there was about a meter of snow accumulation. We had anticipated, all right, it’s the summer. We’re probably not going to get that much snow accumulation, if anything. We’re actually anticipating we might get a little bit of melt. That was not the case.

We landed at about 4 PM in the afternoon. Now we’re so far north that the sun doesn’t set, so thankfully, we don’t have to be worried about, “The sun’s going to set in an hour. We’ve got to get tents up.” But yeah, we landed, and the first thing we had to do was, all right, let’s find the shovels. So I think, yeah, we landed at 4. By 11 PM, I think we had our food tent up, our sleeping tents up, and the bathroom tent up. By I think maybe 2 or 3 AM, we finally decided to call it a night and go to sleep.

But yeah, that first night in the tent, we threw out the original plan. We’re like, “Clearly there’s not enough time to get things done that we want to.” Since it took nine days to get into the field, we knew it may not be so easy getting back out of the field. We can send them the weather reports and say, “Hey, no, the cloud base is actually much higher. You can land,” but if there’s fog, there’s fog. They can’t come.

This was later in the season, so by now, we’re at mid-August. We have students with us. We have to get back so they can attend classes. We have other obligations. We can’t stay out here indefinitely. Plus it’s Greenland. There’s not exactly a commercial flight every single day, so the longer you stay out there, you more risk you have of … I don’t want to say getting stuck in Thule, but being unable to leave Thule. So we know that pushing back our pull-out date is not really an option that we want to go with. It’s something that we considered, but again, it’s a safety issue.

So yeah, the first night, we had to sit down and be like, “All right, realistically, how long is it going to take us to dig out food caches? Dig out our instruments? Can we actually get the experiments done that we want to?” One of the things we were going to do was repeat an active source experiment with our small array of seismometers, but it turns out they got buried and their solar array stopped working. So we’re all like, “All right, I guess we’re not going to do that experiment because we don’t exactly have time to recharge them and get them turned back on.”

The biggest challenge was these bear barrels that were full of food. Instead of bringing out every single food item that we needed with us, the installation team left some behind. But these bear barrels, they’re not like the cute little one gallons that you can get at REI. These are probably three and a half, four feet tall because they came up to my shoulder, and you can’t physically wrap your arms completely around them. They’re maybe, I don’t know, two and a half feet in diameter. I have a photo of my advisor, who buried them, and when he buried them, the hole he dug was probably up to his head. You’ve got to imagine that the barrels are probably about almost two meters below the surface, and then there’s a meter of snow that just got buried.

So it took two full days to just get them unburied to the point where we can screw the top off and get our food out. The entire time we’re doing this, we’re thinking, “Just think of the butter. Just think of the Oreos that are there.” Yeah, we turned into a little bit of Paula Deen with our obsession with butter. Camp food is an entire different podcast, I’m sure, but that was our motivation is get to the hummus. Get to the cheese. Get to the chocolate. Once we got it unburied, it took all six of us to get these out of the ground.

The Ski-Doos were also a big issue. Some of our instruments were a kilometer away, and I’m not saying it’s impossible to walk it. It’s just not feasible, and then with the equipment, it’s just much [inaudible 00:24:29] with a Ski-Doo. But when they’re then buried a meter under the snow, you can’t just dig a vertical hole. You have to dig a ramp to then get the Ski-Doos up.

I forget what the original budget was for how much time it would take to dust off the equipment, which is what we were thinking because we thought it’d be at the surface, but it was seven total days of digging.

Nanci Bompey: Yeah, these guys had a lot of trials and tribulations, but I feel like that bad one, it was that delay. Just that, ugh, flight delay. Have you ever had a really bad flight delay?

Shane Hanlon: I’ve been fortunate enough that I really haven’t had really bad ones, but my worst one … It was an overnight type deal, but it was O’Hare. The only time in my life I’ve ever been to O’Hare, I got delayed and had to sleep outside of baggage claim behind a kiosk on top of my suitcases.

Nanci Bompey: Are you serious?

Shane Hanlon: I’ve never been back to O’Hare since.

Nanci Bompey: Gross.

Shane Hanlon: Not happening.

Nanci Bompey: Gross.

Shane Hanlon: So not quite this. Not as bad as Angela, but that definitely scarred me for life.

Nanci Bompey: Ugh. Ew.

We have one last story, who comes from Sarah Strand at the University Center in Svalbard, which is a Norwegian archipelago near the North Pole.

Sarah Strand: My name is Sarah Strand, and I’m a PhD candidate at the University Center in Svalbard. I live on Svalbard full-time, and I’m also working as the executive director of the International Permafrost Association. I study permafrost, not so surprisingly. I’m mainly focused on permafrost temperatures, what’s happening over the period of time that we have our data, which is about a 10 year series now, as well as the dynamics in terms of the seasons as the active layer, which sits on top of the permafrost, is freezing and thawing with the summer and winter.

Svalbard is an island that is halfway between Norway and the North Pole, and it is known to have more polar bears than people. We’re about 2,200 inhabitants here. I do live here year round, and there’s a lot of science that happens with people who don’t live here, but they come here for their field work. That’s really common. But there’s a core group of us, some at the Norwegian Polar Institute as well as some at the University Center here, that we actually live here full-time. In August, it will be five years, actually, that I’ve lived here full-time. I love it.

Any time you’re leaving the town limits in Longyearbyen and Svalbard, you need to have a rifle with you for polar bear protection. I would say it’s fairly hard to forget entirely the rifle, but it has happened to me before and definitely other colleagues where … There’s quite a lot of routines of how to safely have the rifles of Svalbard, so when you’re in town, the bolt, which actually is the action that fires the rifle, you store that separately from the weapon. It’s much safer that way, as well as the bullets, but of course that means that sometimes it is possible to actually end up with a rifle and perhaps not the bolt, or maybe you have the rifle and the bolts but not the bullets. Of course, you need all three pieces to have a functioning system.

I’ve never had any dangerous encounters. Actually, at this closer field site, I’ve never seen a polar bear. Polar bears do come into this valley, but very rarely, and I’ve never been out when one has been there. So I luckily have not had any dicey situations in that regard.

But there’s also been situations on Svalbard where the weapons can actually freeze sometimes. If snow maybe gets on the gun, and then it melts, and then it sits outside, then it can freeze. There’s actually been some accidents where people have encountered a polar bear, needed to shoot, but then had a frozen weapon. Yeah, but luckily, that has not ever happened to me.

I’m no polar bear biologist, but at least from what I’ve heard and learned over the years, I do agree that they might actually seek out people, but I think it requires very special circumstances. It needs to be the type of bear that’s maybe more interested versus more scared of humans as well as a time of year when they’re really short on food and very hungry. Then they might really seek out people more, definitely.

Longyearbyen people joke about cabin bears, meaning certain polar bears that have learned over time that breaking into people’s cabins is a good way and an easy way to find food, and then these mother bears actually will teach their cubs that cabins are something you should break into. Then these families are repeat offenders, breaking into cabins.

Josh Speiser: Shane, you are a biologist.

Shane Hanlon: I am.

Josh Speiser: Have you had any encounters with charismatic macrofauna that put your life in danger in any way?

Shane Hanlon: No, I dealt with mainly frogs, salamanders, and maybe a snapping turtle you’d have to be worried about once in a while, but nothing that you have to carry a gun with you for.

Josh Speiser: Not usually, unless they’re very large, too large turtles.

Shane Hanlon: Right.

Josh Speiser: The one story that we often hear is that the most interesting that you can hear in science is not eureka but, “That’s interesting,” the idea that sometimes the things that we encounter in the lab or in the field that we think are mishaps are indeed what teach us and lead us on the best direction and really help us attain the best conclusions. In many ways, these “field work mishaps or fails” are really learning experiences. So it was really fun to put them together and to hear these scientists give their stories.

Shane Hanlon: I want to bring Josh around with me all the time.

Nanci Bompey: It’s a real uplifting message.

Shane Hanlon: Yeah. He’ll just be like, “Shane, that wasn’t a failure. You did really well. It’s a learning moment.”

Josh Speiser: Yeah, I’m here for you guys.

Shane Hanlon: All right. Well, that’s all from Third Pod from the Sun.

Nanci Bompey: Thank you so much to Josh, and Lauren, and Olivia, and Katie for bringing us all of these great stories and producing this episode, and of course thanks to all of the scientists for sharing their work with us.

Shane Hanlon: And thanks to Kayla Surrey for producing this episode.

Nanci Bompey: AGU would love to hear your thoughts on our podcast. Please rate and review us, and you can always find new episodes wherever you get your podcast and at thirdpodfromthesun.com.

Shane Hanlon: All right. Thanks, all. We’ll see you next time.