CE13 – The Johnstown Flood: A Most Avoidable Tragedy

View of the South Fork dam after repairs by the South Fork Fishing & Hunting Club, prior to 1889 dam breach.

The Johnstown Flood occurred on May 31, 1889, after the failure of the South Fork Dam, which is located on the south fork of the Little Conemaugh River, 14 miles upstream of the town of Johnstown, Pennsylvania. The dam, constructed to provide a recreational resource in part to support The South Fork Fishing and Hunting Club, broke after several days of extremely heavy rainfall that liquified the dam and blew out the earthen structure, resulting in a torrent of water that killed some 2,200 people.

In this episode of Third Pod from the Sun, Neil Coleman, a professional geologist who resides just outside of Johnstown and teaches geophysics part time at the University of Pittsburgh at Johnstown, describes how a confluence of greed, poor engineering decisions, and hydrology led to one of the most catastrophic disasters in American history.

Coleman also delves into the formal investigation of the event by American Society of Civil Engineers that was subsequently buried, the cast of characters – including the leading steel and rail industrialists of the era – who were involved, the lack of accountability for the victims – save for a re-coop on the loss of a few barrels of whiskey, and the impact on the region that echoes to this day. He also provides insight into how the flood serves as a case study for current day hydrologists and engineers hoping to prevent, respond to, and investigate current and future flooding events.

Transcript

Shane Hanlon: Hi Nancy.

Nanci Bompey: Hey Shane. So today’s episode-

Shane Hanlon: Ooo…this is different.

Nanci Bompey: … is going to be about mistakes and sort of learning or maybe not learning from your mistakes, which I’m sure we all have examples of this, but I’m sure you have a good one to tell us.

Shane Hanlon: Yeah. When I was in college, my car got stolen. It’s this old piece of junk, Buick Century, like 1989, as old as I was. And so it’s stolen from wherever it was parked and I locked it and all of that but like nothing you can do, it’s gone. Six months later I get a call from my dad saying, hey, we found the car. And it turns out it was just in some neighborhood collecting parking tickets and some guy got into it and got his information. So we took the car home, it wasn’t that much damage to it, but he fixed it up and he installed like a kill switch on it, where it was like you have to flip this switch to turn the car on, like it disconnected a fuse. And so he’s like make sure every single time you like get out of the car, you flip this fricking switch. And I did, like religiously-

Nanci Bompey: I can see where this is going, maybe.

Shane Hanlon: … flip this switch every single time. A few months after I got it back, the car got stolen again and we found it the next day because they broke the window and it went home and it never came back to Pittsburgh, that’s where I was living. It’s fool me once, fool me twice…

Nanci Bompey: Wait, but had you flipped the switch?

Shane Hanlon: To this day I thought-

Nanci Bompey: You can’t tell that you flipped the switch.

Shane Hanlon: … that I flipped the switch but I actually don’t know that I did.

Nanci Bompey: Right. You’ll never know.

Shane Hanlon: Welcome to the American Geophysical Unions podcast about the scientists and the methods behind the science. These are the stories you won’t read in a manuscript or hear in a lecture. I’m Shane Hanlon.

Nanci Bompey: And I’m Nanci Bompey.

Shane Hanlon: And this is Third Pod from the Sun, Centennial edition.

Nanci Bompey: So talking about mistakes, did you actually learn from this mistake, Shane?

Shane Hanlon: I don’t know. We’ll never know.

Nanci Bompey: We will never know. Unless, you get a car with a switch.

Shane Hanlon: Right, right. I’ll let you know if I get another piece of junk car. But probably not.

Nanci Bompey: Probably but unlikely. But today’s story actually is about learning from actual mistakes or scientists learning from mistakes that occurred.

Yeah. Yeah. And so for this story, we’re going to bring in our co-producer, Josh Speiser. Hi Josh.

Josh Speiser: Hi guys.

Shane Hanlon: So what do you got for us today?

Josh Speiser: I have the story of the Johnstown flood.

Shane Hanlon: Woooh. I’m from the Johnstown area.

Nanci Bompey: You know of this flood?

Shane Hanlon: I do. It’s in rural Pennsylvania. Have you Nanci?

Nanci Bompey: I feel like I’ve heard about it in songs or something like that, but I don’t know the details.

Shane Hanlon: Yeah. Well Josh, tell us about it.

Josh Speiser: Sure, well here’s the cliff notes version. So we spoke with Neil Coleman, Neil Coleman is a hydrologist who has studied the Johnstown flood. And it’s an epically tragic event that happened on May 31st, 1889 in which there was a dam above a rich hunting lodge that failed and a whole torrent of water came down the Conemaugh Valley, and it washed away several towns, and killed over 2,000 people. And it’s really the story of things that went wrong, and since then hydrologists have been looking to it as an example. And it’s also the story of greed, so it takes in a lot of different areas that are of interest.

Neil Coleman: My name is Neil Coleman. I am a professional geologist here in Pennsylvania and I teach geophysics part-time at the university of Pittsburgh at Johnstown.

Josh Speiser: And just to situate us, how far are we from Johnstown right now?

Neil Coleman: It’s about one hour drive from here.

Josh Speiser: So the Johnstown flood, it really was a human made disaster. It was the result of a group of wealthy folks who had a hunting lodge, which was above what’s essentially was an earthen dyke. And in an effort to kind of cut corners, they remodeled the dyke and when a massive rainstorm came, it overflowed and liquified the entire dyke, which we’ll learn about, which is a crazy process. And unfortunately the communities that were beneath the dam and the dyke suffered and there was a huge loss of life, huge loss of life.

Shane Hanlon: Yeah, it’s wild. I’m from that area. I grew up, Oh geez, like 20 minutes from Johnstown in a small little rural town. But we would go, like Johnstown is our town that we go to that has the mall. And so you go by, like the Johnstown floods is not actually where it happened, it’s like up the valley from there. But you go by where the dam used to be. There’s a big hole in the side of the mountain and there’s a museum there and I was actually museum a few years ago, I took my partner there one of the times we went home. And it’s so funny because it’s just something we learned about in school and all of that.

Josh Speiser: Exactly.

Shane Hanlon: And we like literally take field trips to the museum. And there was this very iconic photo that you can see depending on where you’re getting this, but go to the website, you’ll see this photo of a tree sticking out of a building at a 90 degree angle and that’s replicated in the museum.

Josh Speiser: It’s crazy. Yeah.

Shane Hanlon: Like it’s so wild. It’s interesting, now that I can talk about this.

Josh Speiser: Yeah. I think that’s exactly the point. I’m not from there, but even as you go to that location, you realize that while this event happened over a hundred years ago, it still looms large in people’s imagination. They still say, when they’re referring to geographic areas, they’ll, turn here where you know the flood happened in this area. It’s still very much omnipresent in people’s memory, which tells you a lot about how devastating this incident was and how we need to continue to learn from these types of events.

Josh Speiser: For our listeners who may not know, if you could give us kind of a… If you would transport us back to 1889, what led up to the tragedy?

Neil Coleman: I grew through the history of the dam at South Fork and how it played a role in the Pennsylvania canal system. They’re actually two dams, the one at South Fork, which is East of Johnstown, and then the one at Hollidaysburg, which most people don’t know about anymore. That dam is still there, but you’ve never heard of the flood of Hollidaysburg because that dam was intentionally breached at a low flow time. These dams had an important role in the canal system in that the canals to the East of Hollidaysburg would not have enough flow in summertime to allow the canal boats to travel. Same thing was true on the Western side of the Allegheny mountains, needed additional flow to supply water to the canal basin in Johnstown.

In between those dams was the imposing topographic barrier of the Allegheny mountains. And a series of inclined planes were used to transport goods over those mountains from the canal system to the East, to the canal system on the West. But not long after the dams were built and serving their functions, the railroads developed new routes, especially the one West of Altoona involving the famous horseshoe curve. You could now transport goods directly over the mountains by rail without transferring everything to and from canal boats. The canal system fell into disrepair, it was really no longer needed. In fact, the State sold it at a bargain price to the Pennsylvania Railroad. And so the Pennsylvania Railroad came in possession of the two dams, the Hollidaysburg dam and the South Fork Dam.

One of the Railroad employees who became a Congressman, John Reilly, purchased the property around the South Fork Dam. Now while it was in possession of the Railroad, there was a partial breach of that dam in 1862. A small flood occurred but most people in Johnstown didn’t know that could happen and it was left in that state. In fact, John Reilly, when he bought the dam, it was in that state, there was no large lake there. He eventually sold the property to the group that formed the South Fork Fishing and Hunting Club.

Josh Speiser: Tell us a little bit about the club.

Neil Coleman: The South Fork Fishing and Hunting Club was mainly wealthy industrial Pittsburghers. Some of the most famous of whom were Andrew Carnegie, Henry Clay Frick, and it’s not well known that Andrew Carnegie’s brother Thomas was also a member of that club. It’s an interesting who’s who of Pittsburghers at that time. Also, Robert Pitcairn, who was the superintendent of the Western division of the Pennsylvania Railroad. Very powerful railroad executive and a lifelong friend of Andrew Carnegie. They were runners in a telegraph office together as young boys. Both were immigrants from Scotland.

Josh Speiser: It’s really a who’s who of the elite at that time in that area.

Neil Coleman: Yes, and quite a few of the members of the South Fork Fishing and Hunting Club were also members of the elite Duquesne Club, which still exists today in Pittsburgh.

Josh Speiser: You were talking about the Hunting and Fishing Club, they purchased the area and then what happened?

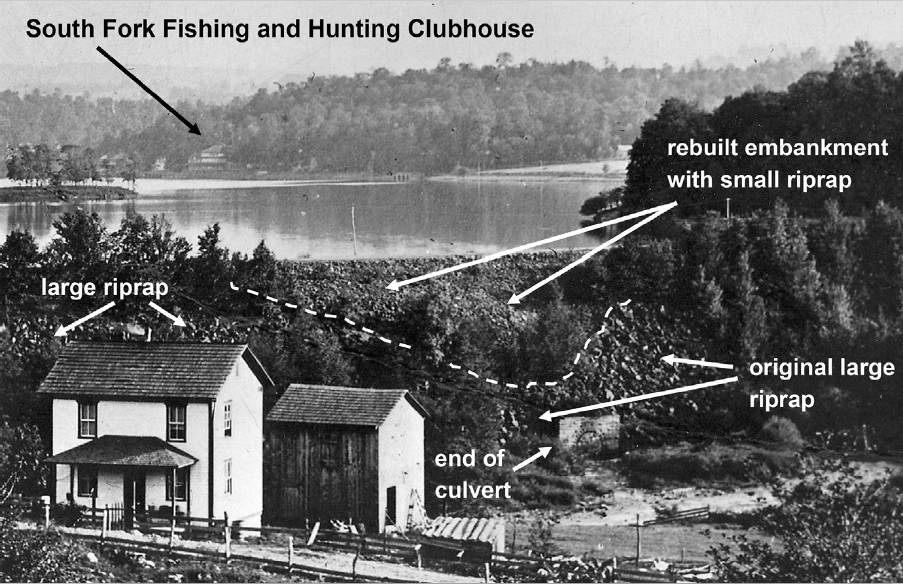

Neil Coleman: The club had to do repairs on the dam before the lake could be reformed. And the five large drainage pipes that had been at the base of the dam, this is what was used to supply water to the river system and to the canal in Johnstown, those pipes were removed. In the research that we did, we’ve come to the conclusion that it was actually club people that removed them before the property was transferred from John Reilly to the club.

Josh Speiser: Not engineers, club people?

Neil Coleman: Well, it was laborers that were hired. I’ve found the original newspaper ad for the 50 laborers that were to begin the work of repairing the South Fork Dam. But they began this work five months before the property was transferred to the club itself. And story is that John Reilly wanted the scrap iron from those to be sold to make up for the, he didn’t make any profit on selling this property to the Club. However, he would have made significant money on the 70 tons of cast iron that came out of those pipes. Removal of those pipes was a very unfortunate thing for the future though because once the dam was repaired, there was no longer a way to lower the water level to do any necessary repairs

But the single worst thing that happened was the Club did not involve any qualified engineers. What they really needed was a damn engineer, a hydraulic engineer to come in and tell them that they should not lower the dam. They lowered the top of the dam, the part that was not damaged, they lowered it at least a meter. This dramatically reduced the amount of water that could safely pass through the spillway of the dam. And the designer of the dam, a Pennsylvania engineer had provided for an emergency spillway on the Western side of the dam. By lowering the crest of the dam that emergency spillway no longer functioned. So the net result of lowering the dam was it could safely pass only half as much water. Once that happened, the South Fork Dam was doomed as were the towns below it in the little Conemaugh Valley. It’s simply a matter of time until a sufficient rain storm came along that the flow into the reservoir exceeded what the spillways could carry and there were no longer the discharge pipes to help with that

Shane Hanlon: This, on a much larger scale of course, this reminds me or makes me think about having bad contractors at your house, your residence. I’ve always rented, but have either… You ever had like bad experiences with contractors or know someone-

Nanci Bompey: I’ve heard so many horror stories, like people that just stop halfway through the job, you know what I mean? Or like you paid them and they never show up or they just like leave for months at a time. But I mean it’s not like that happens because like if they get a bigger job and your job is only not that big, they’re like peace.

Shane Hanlon: Right. Well, I mean imagine that except the consequences are like you don’t get your siding or your new door or whatever. I don’t know. But think of that except like lives, that’s the Johnstown flood.

Nanci Bompey: Right. Right.

Josh Speiser: Exactly.

Josh Speiser: It was an extraordinary rain event. Take us back to that day.

Neil Coleman: It was, there was a young engineer named John Parke who had training at the University of Pennsylvania, although he never earned a degree there. He went to work for the Pennsylvania Railroad and apparently through his contacts got a job to install a sewer system at the clubhouse. The club membership had grown and they were having so many members, let’s just say that outhouses were not sufficient to handle the number of people that were coming. So he came up there to install a sewer system with a team of laborers. And it was his observations that give us the most information about what happened at the lake that day. He went to bed around nine o’clock the night before, this was the evening of May 30th and there had been a little bit of rain, but there was no rain when he went to bed. He woke up early the next morning and the lake had risen rather dramatically overnight. There was a heavy downpour, which it’s estimated approximately eight inches of rain fell over the watershed.

Josh Speiser: Can you give us a sense, was it an earthen dam or how was it constructed?

Neil Coleman: The South Fork Dam was an earthen dam and the original construction by the State was really quite good. The Lake side half of the dam, if you were to look at it in cross-section, used what was called a puddled clay method where they rolled layers of clay. This was to prevent water from penetrating into the interior of the dam and it was an old technique and it actually worked quite well. But when the partial breach of 1862 happened, and as I say, that was not a catastrophic thing, most people weren’t aware it even happened, it left a breach in the center of the dam. When the club began filling that in, they did not use the stratified rolled clay method at all, they simply randomly put material in, earthen material, rocks, whatever they could find locally.

The net result was, on the day of the flood when you had this really high stand at the lake that reached overtopping levels, the spillways couldn’t handle the flow. Water was able to penetrate the dam and saturate it. And so when the final break in the dam happened, the whole center of the dam moved away. It was what we call a liquefaction failure. It turned from a solid into a semi liquid and simply moved away. That’s the expression that was used by one of the witnesses.

Josh Speiser: What physically happens when a substance, for example, the earthen dam liquefies, then what happens with the water?

Neil Coleman: Since the repair to the dam that was done by the Club did not use the rolled clay method, there was no longer a way to prevent water from deeply penetrating the dam, and there were a number of leaks that they reported and repaired over time. This was happening because they didn’t use this method of trying to make the lake side of the dam profile of low permeability. That’s what the clay does, it keeps water from deeply penetrating. But by just randomly dumping material into the breach and filling it, water could easily penetrate it. Now this kind of dam, an earthen dam, it’s also called a gravity dam because it’s simply the weight of the material that you’ve piled up that keeps it in place. Very different from a concrete dam or a dam with a steel barrier in the center of it.

So, when a very high lake stand was reached, you had large fraction of the void, the empty space inside the dam filling with water, and at some point the pressure on the lake side of the dam becomes so great. What really happened, initial overtopping happened and a small notch appeared and it was just enough that the center of the dam had a great weakness in it, and then the fact that water had penetrated the whole center section of the dam, the whole center just abruptly moved away. This was a tremendous wave of water that traveled down the valley of the South Fork of little Conemaugh to the first town that it came to which is actually the village of South Fork and that’s where the railroad ran. It struck the hillside there. And actually water flowed downstream and upstream. The volume of water was so great it forced flow backwards upstream up the little Conemaugh-

Josh Speiser: Quite literally defying gravity.

Neil Coleman: When you have that depth of a flow striking the hillside there, that’s what dominates the river flow. Now it didn’t last too long, eventually the backwash came back. Curiously, the train station, which was located down by the little Conemaugh river was caught in that backflow and actually floated off its foundation and floated upstream some distance. Then as the backwash proceeded, it floated back down to approximately where it was. This is how we know the time of the dam breach because there was a station clock at the South Fork Rail Station.

Josh Speiser: So there was this clock that was quite literally part of the building, which was washed away that gave us a time as when this-

Neil Coleman: The building was not destroyed it’s simply floated for a time like a boat. It went upstream slightly and settled back almost where it had been. It was actually the telegraph wires stretched across that stopped it and deposited it near its original location. But the clock had been knocked out of plumb, so it stopped at that moment. The water spread out, the flow then proceeded down the little Conemaugh river toward the famous viaduct bridge, a beautiful single arch stone bridge, magnificent construction built by a Scottish stone mason named John Durno. He and his team had built this. At that point there’s a huge meander bend in the river, but the flow was so deep in the little Conemaugh river it actually flowed over a sort of a gooseneck of terrain, flowed down the other side where the foundation of the viaduct bridge was located. Water continued around this gooseneck meander bend, debris clawed the single arch bridge, the viaduct bridge until the flood water rose all the way to the top of the bridge.

At this point, the pressure was so great that finally the stone bridge collapsed. And then a renewed flood wave went coursing down the valley.

Josh Speiser: Were people living on both sides of the bridge? Tell us the community in Johnstown.

Neil Coleman: There was almost no one living near the bridge and I’ve never read an account, personal account of it. People heard it collapse, but there was no one actually living there and no one living there today that I know of inside of it. Now the flood wave continued down the little Conemaugh Valley reaching Mineral Point causing destruction, there was a small village. And of course severe damage to the rail lines and the telegraph powers along the way. Finally reaching East Conemaugh and there were passenger trains pulled up there, and I mentioned earlier that the report produced by the ASCE investigators criticized people that ran for their lives from the trains in East Conemaugh and that they should have stayed put. It’s true that passengers that stayed in one of the trains got very wet, but they did survive. But the passengers in the train that was closest to the river who had the farthest distance to run to safety all lived because they had gotten early word from their conductor who’d been to the telegraph power and he said, it is expected that the dam will go and we should be prepared to run.

Now, the reason they didn’t run right away is it was raining outside at that time. But these people who included a group of thespians from Johnstown, they were on their way to another performance to the East. They had their coats on and they had their handbags in hand and the conductor apparently heard the flood coming. He said, “It looks like it’s coming.” They all ran, all lived, they had the furthest to go. So the ASCE investigation report contains a lie. This came out in the testimonies that people gave to the Pennsylvania Railroad that in fact if they had had some sufficient warning, they could have all escaped, those that were physically able to escape.

Josh Speiser: Are you saying that by your literal placement on the train, that dictated whether or not you survived cause you had more distance to run?

Neil Coleman: No. The people that had advanced notice that there was a dam that was getting ready to breach and it could go at any time, that had been given this information. It was claimed later that railroad employees and train passengers all had been informed about this. That is not true. And that came out in the testimonies. So some of that dialogue that was put in the investigation report, the engineering investigation is simply not correct. It was put in there as a protection against liability suits, and shows that there were influences on the preparation of that report outside the four investigators. The damage is actually very much what you would see in a large tsunami. In fact, many of the witnesses didn’t see water for quite some time. They saw buildings being destroyed, in some cases lifted up.

When you look at tsunami damage we now have on YouTube, you can look at movies taken in Japan, in Indonesia of tsunami. These are short films taken by survivors who were photographing this, I can just imagine what was going through their heads, wondering if they themselves would survive, showing how the destruction happened. And you can also get a rolling motion where debris crashes down on victims themselves. Swimming is not how you survive. You’re survive by sheer luck if you’re able to grab hold of the largest debris that doesn’t get thrown under.

Nanci Bompey: So when I think of a dam, which to be honest, it’s not that often.

Shane Hanlon: No, it’s not like part of you’re-

Nanci Bompey: I mean, come on, I’ve lived in several different lake cities my whole life. There are dams.

Shane Hanlon: Yeah. Where do you think like water comes from, like you’re own drinking water? Most of the time… Doesn’t matter. Go ahead.

Nanci Bompey: Okay. But I have been across like these big, big dams.

Shane Hanlon: Sure.

Nanci Bompey: They’re like these big concrete things, more like beaver dams.

Shane Hanlon: Yeah. Made of wood. Right? That’s what’s wild about this. It’s the idea of like an earthen dam. And again, I think even in my mind, I always think of it as being like this wooden thing, even knowing that it’s not, but I can imagine being in like the path basically. Yeah. Like he said, it literally just dissolves. And then you have all of this mud, this earth and then it’s like a very terrifying mudslide, but that’s like a river, isn’t that right, Josh?

Josh Speiser: Yeah.

Shane Hanlon: You’re basically just consuming everything in the path.

Josh Speiser: Not just the water, it’s the debris, it’s trees and worse this case it was actually even part of a railroad and it’s all coming down at this incredible speed and rate with this volume of water. And I mean if you’re actually in the way of this entire field, you have very little chance to survive, if you do survive, you’re quite lucky.

Nanci Bompey: Like a tsunami.

Josh Speiser: Like a tsunami.

Shane Hanlon: Yeah.

Josh Speiser: Exactly.

Nanci Bompey: Yeah.

Shane Hanlon: I remember reading a book, I forget who the author was, but it’s, it’s Johnstown flood book, and they have like firsthand accounts from it and it’s just, Oh man, it’s, yeah, it’s terrifying.

Josh Speiser: Yeah.

Josh Speiser: And how many people perished, do we know?

Neil Coleman: No one knows how many people actually died? The official number had long been 2,209, but one of the people who was thought to have perished named Leroy Temple came back in the year 1900 to visit his old friends in Johnstown and let them know that he was a lively Yankee yet. He was from Beverly, Massachusetts and he had been living in Johnstown, he was married to a lady named Viola. She had children from a previous marriage. He was caught in the debris, carried all the way down to the stone bridge, which is where this enormous field of debris collected. He was close enough to the bridge that there was a an earthen embankment on the North side of the bridge. It was washing out. The bridge itself and the debris caused a huge lake, a terrible, very dismal lake. Some survivors on the top of it, many victims in the debris field.

But Leroy Temple made it all the way down to the railroad embankment and in fact the embankment had washed away and rails and tires were hanging in the air. Leroy Temple reached up and grabbed a suspended rail, pulled himself out of the debris. He was badly injured but he recovered enough in several weeks and train travel was reestablished. He and his family left. So the official death toll should be 2,208 because Leroy Temple did survive.

John Parke wrote a letter, which was sent… See right after the flood, the American Society of Civil Engineers put together a team of investigators to send, and that really is what my book was about because very little has been said about that formal investigation. And it was only the second dam breach investigation that the ASCE had done. ASCE had been founded in the 1850s. They put together, just really a few days after the flood, a team of four engineers, and as soon as railroad transport was possible to the Johnstown area they went and did their own fieldwork, did their own surveys of the dam remnants, interviewed local people. And the apparent leader of this team was an internationally renowned hydraulic engineer named James Bicheno Francis from Lowell, Massachusetts. He was the, shall we say, the architect of the industrial revolution, the ultimate use of water power, not water power for generating electricity, but actually using the motive power of water to drive industrial engines.

He was the apparent leader of this investigation. There were two other hydraulic engineers, William Worthen of New York and Alphonse Fteley, an immigrant from Paris who was actually a protege of Worthen’s. These three gentlemen were premier hydraulic engineers. They’re the kind of people you wanted in this sort of study. The fourth member was the present president of ASCE in 1889 and he was a railroad engineer named Max Becker.

Josh Speiser: This is the day following the dam breach.

Neil Coleman: The group of investigators was chosen less than a week after the flood. They visited in the middle of the month, that is about two weeks after the flood, so that would be mid-June 1889. I haven’t been able to find details of who marshaled the total report that they put together. It is a state-of-the-art investigation report for the time filled with the imagery, tables of calculations, appendices, a detailed history of the dam, but as my research details, there were very substantial problems with this report. Some things that were incorrect and I don’t know if they were done incorrectly to make things look more favorable for the club.

Their purpose was to go study why the dam breached, why did the failure happen. And it contains oversights that were simply not plausible by engineers of this caliber when I know for certainty that they did the surveys of the dam remnants themselves. I’ve read a description of them carrying the survey instruments over the dam remnants. They reported their measurements to very high accuracy, down to better than an inch in terms of elevation profiles. Yet, there is no mention at all of the emergency spillway on the Western end of the dam. It is that which would have saved the dam had it never been lowered by a meter. Their calculations did not include the emergency spillway, no mention of it. I believe this report was edited in a way very favorable to the club.

And it contained things that had nothing to do with the dam breach, comments on train passengers in East Conemaugh far downstream. And some of the things are things that I find very irritating when I see a suggestion that people died because they ran for their lives, had they stayed in the trains where they were put, they’d have survived. This was put in by someone with an eye toward liability of the railroad and liability of the club members themselves.

Now Max Becker who was then president of ASCE, he was a railroad engineer, not a hydraulic engineer, it turned out, although it appeared that James Francis, the internationally known engineer was leading the investigation, Max Becker decided what happened to it. And in fact they completed the report, they started working on it in June of 1889, they completed it by January of 1890, it was turned in and sealed. The new president of ASCE was William Shinn, who had been a managing partner with Andrew Carnegie. He was not a member of the South Fork Fishing and Hunting Club, but he was a member of the Duquesne Club in Pittsburgh with Carnegie and others. He handed the report to Becker and said, release it when you feel the time is right.

It turns out the time would not be right until two years after the disaster. And this is terrible because there may have been other towns, other people, other infrastructure and businesses at great risk due to similar problems at the South Fork Dam and that report needed to get out so people would know these things. But in fact, Max Becker sat on the report, it was not released until the ASCE convention in Chattanooga, Tennessee in 1891. Chattanooga, far from Johnstown, simply sat on it.

And at some point aspects of the report were sanitized. It’s interesting that the report even includes a line that says, had the club not lowered the dam, the flood may have been even worse because it would have impounded more water. Well, that part of it is true, but in fact, if the dam had been higher, you’d have had two functioning spillways, never would have been overtopped based on all the information that’s available. But when I read things like that in an investigation report, it makes you want to dig deeper and that’s what we did, found so much there.

Thanks to the freedom of the press. Much of what we were able to learn comes from freedom of the press, from the Johnstown newspaper, from Pittsburgh newspapers, from Engineering News, which was the key trade journal at that time, but there were several others. This was critical for understanding what happened, reading stories and for example, James Francis told a reporter from the Johnstown Tribune that it was Max Becker who was sitting on the report, was delaying it, did not want the investigation committee and the ASCE to get involved in any court battles. But in fact, through an analysis of everything that happened in the history and reviewing the report itself and the way calculations were done, the way it was presented, the real reason I believe that this was kept under wraps for two years was they did not want to see eminent engineers like Francis, Worthen and Fteley, eminent hydraulic engineers go into a courtroom, put their hand on a Bible and swear to tell the truth as they saw it, of the South Fork Dam and the club that owned it.

Josh Speiser: Following the investigation you were talking about, were the members of the club or who was held responsible and was there any legal actions? And then I guess if you could talk a little bit about from hydrological perspective, what this taught future engineer, future hydrologists as they approached either analyzing a disaster or trying to figure out building to prevent such a disaster.

Neil Coleman: Let’s take the second part of that first. The big flood that happened in 1936… And by the way, anyone who visits Johnstown, if you go by City Hall, which is right downtown, the flood levels from 1889, 1936, 1977 these are all marked on the corner of the City Hall building of the original City Hall at the time of the flood. The building that served as city hall did not survive, but the new one that was built survived the 1936 and 1977 floods.

I will just mention, we’re seeing in many places in the country some areas that had never had catastrophic floods even in the Midwest now. This is the year 2019 and very catastrophic floods in the Midwest. There is a reassessment going on of where the true flood plains are now and to what extent climate change, global warming phenomenon are leading to this or accelerating it. Some of it is just a statistical matter over time, you eventually have these larger events. The biggest floods that don’t involve dam breaches are those where you still have a lot of snow and then you get catastrophic rains on them. So the flood discharge then involves this cold storage that is rapidly melted along with the rainfall event, those are particularly nasty. And we still have the phenomenon of the probable maximum precipitation, the theoretical upper limit on what can fall. This has been used to develop truly robust flood protection designs.

But there is a responsibility to city planners to carefully research not just what’s going on today, but historical research on where major floods have happened before they approve new developments with tens or even hundreds of millions of dollars of investment by people. I think it should be an important part of city planning, regional planning research. Where is there information about historic floods? Even if one has to go back to pioneer records to read. Great responsibility for these folks. The future lives, future property depend on that. Now the-

Josh Speiser: The legal question.

Neil Coleman: The legal question. There were a number of lawsuits that were filed after the Johnstown flood. No one with the club was ever found accountable. The club itself actually had a minimal monetary value and the dam was essentially gone at this point. The venue for the lawsuits had been moved to Pittsburgh. I guess it was felt there was no way to get a fair jury anywhere near Johnstown. That’s probably correct. But if you can imagine what a jury in Pittsburgh would look like, railroad men. It was all men in those days. Railroad men, steel workers, coal miners, folks working in the coke, you know, converting the coal to coke, which was needed for the steel industry. And these were all people that worked for the industrialists who were the club members. So imagine what it would be like to come out with a guilty verdict against these people. And quite often these were barely living wages that people received.

There was no legal liability ever found for the club members for the club. In fact, the one lawsuit that I’m aware of that was successful was against the railroad. Some barrels of whiskey were in the back of a rail car and they were stolen. The railroad was found liable for the loss of the whiskey. This is all thousands of people killed in this flood. The majority of whom, by the way, were women and children, but no legal liability for that. But barrels of whiskey missing, someone felt there had to be someone punished over that and they were.

Shane Hanlon: So there wasn’t really like, I mean the whiskey, which is of course like someone’s livelihood, but there wasn’t like accountability, right?

Josh Speiser: No, by Neil’s account, no one was really brought to justice, so to speak. And they got away, but the flood took so many lives and no one was left to clean it up and a lot of people were left starting over and moving forward in a brand new way.

Shane Hanlon: Yeah. So, I lived in Pittsburgh for a while and that’s where a lot of these folks were from. And there’s buildings, I mean like Carnegie and Frick and some of those were like part of this club and not just because of like the flood obviously, but there’s art institutions and universities and like all these places named after these people, and it’s a very well-known thing, they’re like these industrialists of the time, would then like use a lot of their money to do great things later, but probably because of they had a lot to make up for. Yeah. So besides just like buying stuff or throwing money, we did learn things scientifically, right?

Josh Speiser: Absolutely. Absolutely. I mean I think for hydrologists, this is a real good case study in maybe what not to do in many ways.

As we look back to Johnstown, as a person who might be studying hydrology contemporary times, how is it looked upon now and how is it used in a context?

Neil Coleman: Well, surprisingly almost no scientific or engineering work had been done since the time of the ASCE investigation of this. Books that had come out, articles that were written, many, many of them, some films even, they all focus on the macabre aspects, the terror and the death of these people, all very hardworking people in Johnstown and it was a key area of Cambria Iron, major producer of iron at that time. There wasn’t really a good example of an engineering or scientific analysis of what happened here. There is enough material here now to show sort of a blend of history, science and engineering and I’m starting to realize there aren’t very many works like this. Were it not for the ASCE report, there’d be a lot of information we wouldn’t have, so a lot of what they documented was very, very useful.

Josh Speiser: If you were to teach a masterclass on Johnstown, again being kind of the case study, what would be few of the major takeaway messages you would want your students to come away with?

Neil Coleman: Any calculations you do, don’t just check them once, check them twice, check them a third time, use alternative ways of getting to the answers. The same would apply to a development of flood plain maps, looking at safety of dams, look at what the precipitation trends are, our growing knowledge… What it is, is we have a more extended database of rainfall events over time, this directly translates to the hydrology of the streams and rivers. So never to be too comfortable with what one believes your calculations and your analysis have shown. And to also look at history, there are some records that are not formal meteorological records or formal hydrology and flood records, but older records that show what people experienced a century and a half, two centuries ago, and see what can be made of that. Use every bit of information available to get a good integrated picture. For human health and safety, one can do no less.

Shane Hanlon: Okay. It’s my, I guess, task as usual to ask you, Josh, what did we learn?

Josh Speiser: So I think, to you use an old axiom, what we learned was the past is prologue. And especially in a time when we’re seeing more floods because of climate change, we have to learn from past actions and this was a real failing and going forward we can hopefully not make the same mistakes that were made before and we can do better.

Shane Hanlon: That’s very deep.

Nanci Bompey: It is very deep. So this actually, you know, I mean take a little sideways term, but this actually wraps up our Centennial episodes.

Shane Hanlon: Oh, it does.

Nanci Bompey: Centennial is sadly ending in 2019 although the legend will live on and we’re continuing these historical stories, but just to look back over a year of these Centennial stories, like what did we learn?

Shane Hanlon: We learned so much? I learned about radioactive waste and-

Nanci Bompey: Lots of radioactivity I feel-

Shane Hanlon: Lots of radioactivity.

Nanci Bompey: … at Cold War. I feel like I got a lesson in the Cold War.

Shane Hanlon: We got a little lost in the Cold War.

Nanci Bompey: I got a lot of historical lessons in a lot of things.

Shane Hanlon: Yeah, well and so much so that we’re going to keep on doing these in some capacity.

Nanci Bompey: So we learned that it was a good thing.

Shane Hanlon: We learned it’s a good thing. We liked it. We hope that you all liked it and there will be more, we’ll say historical episodes to come next year and hopefully beyond that.

Nanci Bompey: Yes.

Shane Hanlon: So that’s all from Third Pod from the Sun.

Nanci Bompey: Thank you so much to Josh for bringing us this story and of course to Neil for sharing his work with us.

Shane Hanlon: This podcast was produced by Josh and mixed by Colin Warren.

Nanci Bompey: We would love to hear your thought on our podcast. Please rate and review us on Apple podcast. You can download us wherever you get your podcasts and of course always at thirdpodfromthesun.com.

Shane Hanlon: Thanks all and we’ll see you next time.