Exhuming a Buried Piece of American History

Carter Clinton (left) and Fatimah Jackson (right) of the W. Montague Cobb Research Laboratory at Howard University. The Cobb lab houses the largest collection of African American skeletal and dental remains in the world. Clinton is Assistant Curator and Jackson is Director of the lab. Credit: Lauren Lipuma.

In 1991, the United States government unearthed a staggering archaeological find during construction of a federal office building in lower Manhattan. While digging the building’s foundations, construction crews stumbled upon skeletal remains from the “Negroes Burial Ground,” the largest and oldest burial site of free and enslaved Africans in what would become the United States.

Historians knew the burial ground to be a 6.6-acre cemetery of more than 15,000 Africans and their descendants who lived in New York during the 17th and 18th centuries. Africans were not allowed to bury their dead in church cemeteries in colonial New York, so colonists gave them a swath of undesirable land outside the original city walls in which to bury their dead.

The burial ground was filled in and covered over in the early 19th century, and it lay mostly forgotten under 30 feet of earth until construction of that office tower in 1991.

Rediscovery of the burial ground changed anthropologists’ understanding of slavery in New York City, according to Michael Blakey, an anthropologist who analyzed the individuals’ remains.

Skeletal remains and burial artifacts of more than 400 individuals were exhumed upon discovery of the burial site, which was renamed the New York African Burial Ground. Thanks to a concerted effort by then-New York Mayor David Dinkins and the local African American community, in 1993 the excavated remains were brought to Howard University in Washington, D.C., the country’s leading African American research university.

Blakey, then director of Howard’s W. Montague Cobb Research Lab, led efforts to analyze the skeletal remains and reconstruct the lives of the individuals interred in the cemetery.

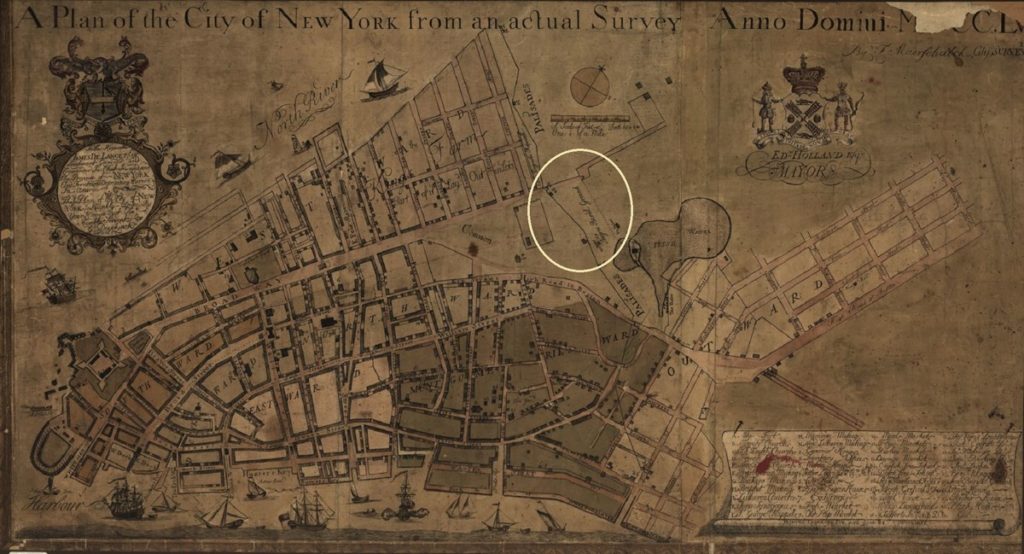

This historic map of the City of New York from 1754 shows the New York African Burial Ground and its surrounding neighborhood. Credit: Library of Congress.

The remains and burial artifacts provided remarkable insight into the lives of Africans in colonial New York. Bones and teeth showed evidence that the enslaved Africans often performed hard manual labor, suffered from malnutrition, and had short lifespans. Artifacts showed anthropologists evidence of the African cultures and tribes from which the individuals came. The burial ground site was designated as a national historic monument in 1993 and the remains were ceremoniously reburied in 2003.

Although the remains were reburied, samples of grave soil from the burial ground remained at the Cobb Lab. In 2015, Carter Clinton, then a graduate student at Howard, began analyzing the soil samples to see if they could tell him more about the lives and deaths of the individuals interred in the burial ground.

Carter’s work, some of which was recently published in Nature Scientific Reports, sheds more light on the diet of enslaved Africans in New York and some of the infectious diseases they suffered from.

In this podcast episode, Carter recounts the history of the New York African Burial Ground and describes what he has learned about the lives of Africans in colonial New York from the grave soil samples. Carter discusses how his work helps shape the narrative of slavery in New York and how it fills in a piece of American history long forgotten.

This episode was produced by Lauren Lipuma and mixed by Collin Warren.

Transcript

Shane Hanlon: Hello, Nanci.

Nanci Bompey: Hi, Shane. It’s a gray day here in Washington, D.C. Our level is subdued.

Shane Hanlon: You’re not excited about this?

Nanci Bompey: I’m very excited.

Shane Hanlon: Be excited. All right. So my question for you today, if you could take one thing with you into the afterlife, let’s say be buried with something, I don’t know if you want to talk about… Nancy’s shaking her head. She does not like this line of questioning.

Nanci Bompey: I want to be cremated.

Shane Hanlon: Okay. What’s one thing that we drop into your urn? Maybe not take it into the afterlife, but what’s a thing that you’d like to take with you to the grave?

Nanci Bompey: That’s a good question.

Shane Hanlon: It’s serious.

Nanci Bompey: My diary.

Shane Hanlon: You have a diary?

Nanci Bompey: I have a journal.

Shane Hanlon: Oh, I want to read. It’s so fascinating.

Nanci Bompey: I do it so infrequently that it goes back so many years that it’s ridiculous.

Shane Hanlon: Oh, see, that’s even better. Is it like a big notebook?

Nanci Bompey: It’s just a little notebook, yeah.

Shane Hanlon: You had a notebook for all these years?

Nanci Bompey: Yeah, so it’s kind of funny.

Shane Hanlon: How far back are we talking here?

Nanci Bompey: Since I graduated from college, which is like 20 years ago. So it’s kind of funny. Yeah.

Shane Hanlon: That’s amazing.

Nanci Bompey: That would be good. Because I don’t want anyone to read it. So I would be buried with it.

Shane Hanlon: Welcome to the American Geophysical Union’s Podcast about the scientists and the methods behind the science. These are the stories you won’t read in the manuscript or hear in a lecture. I’m Shane Hanlon.

Nanci Bompey: And I’m Nanci Bompey.

Shane Hanlon: And this is Third Pod From The Sun. All right, so there is a reason why I was asking Nanci about things to take with you, but to explain this in a way that’s probably much more eloquently than I can do it, we’re going to bring in Lauren Lipuma, who actually did the interview. So, hello, Lauren.

Lauren Lipuma: Hi Shane.

Shane Hanlon: Okay, so can you explain what we’re talking about today?

Lauren Lipuma: Yeah, so a couple of months ago, I interviewed Carter Clinton, who is a researcher at Howard University here in D.C., and Carter was telling me this fascinating story about a cemetery that was discovered back in 1991, along with some remains and some artifacts that were buried with the individuals inside.

Carter Clinton: So, my name is Carter Clinton. I am a PhD candidate at Howard University, and the assistant curator of the W Montague Cobb Research Laboratory.

Lauren Lipuma: So, the Cobb lab was started almost a hundred years ago by William Montague Cobb. He was a pioneering anthropologist in the 20th century here in D.C., and he started a collection of skeletal remains of African-Americans from individuals who lived in the D.C. area and who had donated their bodies to science for one reason or another. And his goal was really to study race. He wanted to show the impact of race on human health. This was a big issue in the 20th century. And he also wanted to provide scientific evidence that African Americans were not physically or mentally inferior, as some people had thought around that time.

Lauren Lipuma: So, the Cobb Lab, over the years, has grown, and now has several different collections of human remains and burial artifacts from African-Americans who lived over the past 400 years from various places. And one of the collections that we’re going to talk about today that Carter studies is a collection of soil samples from the New York African Burial Ground.

Lauren Lipuma: And this was a cemetery for enslaved Africans and then African Americans that lived during the colonial period in New York, during the 17th and 18th centuries. And what Carter has been doing has, is analyzing those soil samples to see if he can reconstruct the lives of these individuals and how they lived and how they died. And interestingly, the burial ground was discovered in 1991 during construction of a federal building in lower Manhattan.

Carter Clinton: So, in 1991, the government went to build this federal building in lower Manhattan, literally at the corner of Broadway and Chambers, Broadway being one of the most famous streets in the country, or maybe the world. And all of these bones just started to come out.

Carter Clinton: So, the thing is, this building was much taller than all the other buildings in the area. So, it was intended to be around 30 stories tall, so they had to dig 30 feet deep. And so, at this depth, that’s when skeletal remains, bones, artifacts started to be unearthed. And so now is a question of what have we just discovered and what do we do next?

Carter Clinton: So, of course they still want to build the federal building at this point. It’s a multimillion dollar project. But the local community actually steps in and says, “Hey, we have to figure this out. If this is the remains of some living descendants, then they’re owed the opportunity to have some voice in what happens with these remains.” And that was mainly the assumed descendant or African American community in New York at the time. It also helped that New York had an African American mayor, David Dinkins, at the time, who was very instrumental in getting this work done.

Carter Clinton: So, they discovered the remains, they halted the excavation. In 2006, they reburied the remains. So, at that location, now stands the federal building that they first intended to build, a memorial to the New York African Burial Ground population, and a visitor center where people can come and learn more about the population.

Lauren Lipuma: At what point during the excavation process, when they discovered all the bones and artifacts, did they realize what it was? That this was an African burial ground?

Carter Clinton: Right, so they went back to historical maps, and the assumption was that either it was sterile land that they were trying to erect this federal building on, or they were not building deep enough to disturb the remains. But the maps clearly show that in this area was the Negros burial ground. So, that’s how it was labeled on maps. And I can’t remember the name of the surveyors. Obviously, before a construction project, you have surveyors who look at the soil profile and the locations to make sure everything is okay. And they’re the ones who actually pointed it out, that was the New York African burial ground.

Carter Clinton: We don’t know the exact year or the origin. It’s assumed that it’s around the 1640s. So, in the New Amsterdam colony, there were 11 slaves who were enslaved to the Dutch West India Company. They actually petitioned for their freedom and were granted a half freedom. So, basically, they were free, but their offspring were not free. And if the company needed them at any point, it would be mandatory for them to fulfill whatever work the company needed.

Carter Clinton: But with their half freedom, they were actually allotted a plot of land just outside of the colony. So, this is just North of where the New Amsterdam colony existed in the 1600s, and then they had to pay taxes every year for that land, to live on that land. And then the hypothesis is, if we’re living outside of the colony, we need a place nearby to bury our dead. We’re not going to carry our loved ones somewhere that’s very difficult to get without transportation.

Carter Clinton: And so this burial ground is hypothesized that it’s adjacent to the Negro frontier. So, that’s the community that was developed by these free Africans. We hypothesize that they started to use this land as a burial site because nobody else wanted it. Right? It was undesirable land. It was marshy. Nobody wanted to build on it. It wouldn’t be disturbed. They didn’t have anything to worry about.

Lauren Lipuma: And so, how many individuals’ remains were in the burial ground? Or how many were excavated? And then do they know how many are there total?

Carter Clinton: So there’s an estimated 15,000 individuals there. It spans about 6.6 acres on the island of Manhattan today. And at excavation, there were 404 individuals, I believe, that were brought to Howard University for analyses.

Lauren Lipuma: And so, then, when the remains were brought to Howard, what did they first discover about the individuals?

Carter Clinton: Well, they were really interested in confirming that these were Africans, African-descended people, and they were also interested in anthropometrics. So, basically, whether it was a male, a female, age, looking at juveniles. Obviously, at that time, there were a lot of infant and juvenile mortalities. And I believe maybe the oldest individual was around 60 years old, which obviously is not very old today.

Lauren Lipuma: So they didn’t have a long lifespan.

Carter Clinton: Right. And also they were very interested in their involvement in New York City’s history. So, we know that New York was built by enslaved Africans, but we don’t really have that narrative in America’s history. We don’t know very much about their role in building even Wall Street, the location of our nation’s, or the global, economy. Right? So they wanted to kind of elucidate all of these stories and this existence about this population.

Lauren Lipuma: Do you know a little bit about some of the analysis, that skeletal analysis that was done on the samples, when they were first excavated?

Carter Clinton: I think these were things that we already knew. So, even seeing lesions on the bone to where the muscle was almost being torn from the bone because of the strenuous labor, or lifting very heavy things. There was damage at the base of the skull for some individuals, and that’s from carrying very heavy items on the head. They also attempted to look at pathologies on the bone, so certain diseases, when they go untreated, you’re able to see lesions on the bone, like tuberculosis or syphilis. So they did explore the remains for those pathologies.

Lauren Lipuma: You were telling us about one particular individual that stood out to you last time we talked.

Carter Clinton: Yeah, so, that’s Burial 25. And so, this individual was a female. She was estimated to be between 25 and, I believe, either 35 and 40 years old. And she had a musket ball in her rib cage, meaning that she died with this bullet in her at the time of death, and she had a fractured skull from blunt force trauma. She had a broken arm, a fractured arm, which shows that there was some sort of struggle. There was either some situation where she fought back. She fought back. She didn’t just succumb to her situation, or this person who was attacking her. Right? And so, in that, I see strength, and that was monumental for me because this is an example of only one individual, but I can only guess the percentage of this population who felt that.

Carter Clinton: With her injuries, with the blunt force trauma and the fractured arm and the musket ball, specifically around the fractured arm, there was bone regeneration, which mean that she suffered these injuries, but she also lived for days afterwards.

Lauren Lipuma: So, the bone was healing.

Carter Clinton: Right.

Lauren Lipuma: Oh, wow. So you can tell that she didn’t die immediately. She suffered.

Carter Clinton: Right.

Lauren Lipuma: Wow.

Carter Clinton: Right. So, she must’ve been in some agony for days before she passed away.

Lauren Lipuma: Wow.

Carter Clinton: So, that just speaks to the strength of this individual in the 17th century, and her will to survive.

Carter Clinton: I started working with the remains in 2015, so unfortunately, well not unfortunately for the remains, they were ceremoniously reburied. But unfortunately for me as a researcher, they were reburied. So, I couldn’t do any analyses on the bones. But we did have the soil that was collected at the same time that the bones were collected. Being from New York and having visited when I was in elementary school, I was very, very interested in this project, in this population, in this location. I wanted to be involved with every part of this project that I could be.

Nanci Bompey: So, since Carter didn’t have access to the remains, because he just started his PhD not too many years ago, they were already reburied.

Lauren Lipuma: Right.

Nanci Bompey: So, he had to figure out what to do.

Lauren Lipuma: Right. So, he really wanted to work on these samples, but the skeletal remains were already be buried. But luckily they did still have soil samples. And so what Carter has been doing is taking the soil, which is basically decomposed human flesh.

Nanci Bompey: Oh wow.

Lauren Lipuma: Yeah, that’s crazy for over 400 years, this is what it has become. And he’s trying to see if, from those samples, if they can tell us anything about these individuals, more than the skeletal remains did. So, can they find out anything about how they lived, what they ate, how they died, and maybe what their lives might been like.

Carter Clinton: My dissertation is really a three-part project. The first is a soil chemistry analysis where we look at all trace metals in the soil. And so, from that, we’re actually making deductions about diets, lifestyles of these individuals, and even the soil profile of Lower Manhattan, where the samples were collected from.

Carter Clinton: The second part is a bacterial DNA analysis of the burial ground soil. So, we wanted to look at all human-associated bacteria, basically just to see what’s there and if we could see evidence of human existence from 400 years ago.

Carter Clinton: And then the last component of the project is the geospatial analysis. So, basically, we take all the data from the first sub-project, the trace metals, all the data from the bacterial DNA analysis, and kind of map them into this 3D digital rendition of what the burial ground looked like. Or at least the excavated portion of the burial ground, because really it’s only a fraction of what existed at one point.

Carter Clinton: And I also have to clarify this. When I present, it’s not plot soil. It’s not from the burial plot. It’s soil compacted within the remains of the individuals. So, even at the time of excavation, when they were collected, they were labeled with the body region that they were collected from. So, for example, we could have Burial 300, and we could have three samples for that individual. So, Burial 300 Cranial Soil, Burial 300 Pelvic Soil, and then Burial 300 Tibial Soil. It was actually compacted inside of the bones and it had to be removed from the skeleton.

Lauren Lipuma: Tell us a little about the trace metal analysis, what that tells you about these individuals.

Carter Clinton: With the trace metal analysis, we were able to analyze up to about 19 elements per sample. But with our samples, we were able to confidently report on five. Those five were arsenic, zinc, copper, calcium and strontium. So, we saw extremely high, or seven fold, increase of strontium in our burial ground samples. And so, when we kind of looked at the scientific literature, when you look at ratios or calcium-strontium ratios, it indicates a vegetative diet.

Carter Clinton: And so, we know this is aligned with the historical narrative. These were enslaved Africans, they weren’t eating protein-rich or very robust diets. And so were eating root crops or leafy vegetable diets. And then also we know that they had to cultivate crops in order to pay the New Amsterdam colony, and so we know for sure that they were growing root crops and leafy crops. The assumption that’s obviously what they were consuming.

Carter Clinton: With the bacterial analysis, we were able to 100% see human evidence. Mainly, what we think is gut microbiota from each of these individual visuals. And interestingly enough, the certain disease pathogen, which only show up in specific burials.

Lauren Lipuma: Like what?

Carter Clinton: So, some individuals have strains of pneumonia, and so we think, obviously, that was their cause of death. We’re seeing evidence of possibly Legionnaire’s disease, possibly cholera, and I say possibly because we need additional analyses just to confirm. Because of the age of the samples, we are only able to distinguish down to the genus level, and so we just need additional analyses to kind of go back and look at specific strains of what we think we’re seeing.

Carter Clinton: But definitely salmonella, which kind of gives us some insight into their living conditions, like spoiled foods or not exactly all fresh foods.

Lauren Lipuma: Food borne illness.

Carter Clinton: Not the most ideal. Yeah. Evidence of dysentery, which was prevalent on slave ships, obviously, because this population was so tightly packed together, or anybody on these slave ships were just so tightly packed together that it just spread throughout the ship. And then they were obviously brought with them to the Americas. So, many different disease pathogens that we think are the causes of death for these individuals.

Carter Clinton: Also, I think that’s one of the very interesting parts of the project, that these bacterial pathogens still exist after 400 years. So we can see evidence of pneumonia, possibly pneumonia or Legionnaires’ disease or cholera in these burial samples.

Lauren Lipuma: Because those kinds of bacteria would not be present in soil normally, only if they had been associated with people.

Carter Clinton: Right. So, not only are we seeing evidence of human existence and 400 year old soil, we’re seeing the microbiomes of these individuals. We’re seeing decomposition evidence in these samples. We’re seeing disease pathogen that still exist in these samples, and then we very well may be able to identify these individuals’ ancestry by their microbiomes.

Lauren Lipuma: Oh, wow.

Carter Clinton: So not to an individual level, but kind of to a, “This reflects what modern African-descended population microbiome looks like today.”

Carter Clinton: The GIS analysis, I think, is the most important. It’s where it’s the comprehensive collection of all of this data. I want to make everything available for the public because I feel like it should be out there for people to know. And also, I would like for it to be incorporated into the monument. So, right now, they have just a 2D map of the burials, whether they were male or female. But if you would be able to have a digital map hanging up, it’s interactive, you can touch it, and you’d be like, “Oh, this is Burial 10.” And, “Oh, they died from cholera.” And, “Oh, they had high levels of strontium. So, we know they had a high vegetative diet.” Or something like that.

Carter Clinton: That’s the end goal, to look at all of these things on that 2D map, but also in a 3D rendition, to see where depth also plays a role. Because we have time periods assigned for these individuals, but nobody really knows for sure because they were unmarked graves. So, the time periods were assigned basically based on the artifacts that they were found with, or the shape of the coffins.

Lauren Lipuma: And so, how do the artifacts and the coffin shape tell you a little bit about the time?

Carter Clinton: So originally coffins were just four-sided boxes or just rectangles, and then, over time, they became octagonal, so kind of that Dracula coffin shape. I think that’s the best way I can convey that. So, we know that those were later coffins.

Carter Clinton: And then the artifacts reflect the pottery existence of the time, and then the rule of the time. So, New Amsterdam actually changed to New York from Dutch to British rule. So, there’s some evidence of when that change occurred, when these artifacts started to show up with British rule, so on and so forth.

Lauren Lipuma: What do you think all this means? All the things that you found?

Carter Clinton: It means a lot on many different levels. I think this is such a huge part of, not just African American history, but American history. For example, even when I go to conferences and I’m presenting the science, people take me all the way back to the beginning and they’re like, “Wait, there was slavery in New York?” It’s like, “Yes, there was slavery in New York, and it’s actually the place of the largest burial site in the country.” Mainly because, in the South, there were plantations and there wasn’t one place where all enslaved Africans were buried. So this was kind of a fortuitous, probably fortuitous is not though the word that I want to use. It was fortuitous for the construction to happen, but it was convenient for these Africans to use one location to bury their loved ones, to be able to do that. That was fortunate for us as researchers to learn something about an entire population.

Carter Clinton: And so this project gives you something to connect to, right? Looking at strictly the numbers, looking at the number of Africans who were trafficked to America and thinking that 15,000 are buried in this one location, then African Americans in the North East region may very well have an ancestor that came from the New York African Burial Ground.

Lauren Lipuma: And so, what does it mean for you personally to be involved in this project and to have done this work?

Carter Clinton: It’s a loaded question. It’s very important for me on so many levels. As a researcher, as a native of New York, I feel as though I have this duty, right? I had this opportunity, I had to take that opportunity, because it’s important for these stories to be told by the right voices. I just feel invested. I feel personally invested in this project. I don’t know. It gives me a sense of completion almost, even as a researcher, just to be able to do this work, have some autonomy, and then have the voice to convey this narrative to the public.

Lauren Lipuma: This was one of the most fascinating interviews I’ve ever done, and actually Carter was telling me he thinks he may even have some ancestors buried in the burial ground.

Shane Hanlon: Really?

Lauren Lipuma: Yeah. He may be one of their descendants.

Shane Hanlon: Oh man. I, for so many reasons, can’t even imagine what that must must be like. Because he’s here and he’s local, I’m excited. We’ll definitely have to keep in touch with him to figure out what he finds and what’s going on later.

Lauren Lipuma: Yeah, definitely.

Shane Hanlon: All right folks, that’s all from Third Pod From The Sun.

Nanci Bompey: Thanks so much to Lauren for bringing us this story, and to Carter for sharing his work with us.

Shane Hanlon: This episode was produced by Lauren and mixed by Colin Warren.

Nanci Bompey: We’d love to hear your thoughts on this podcast. Please rate and review us on Apple podcasts. Of course, listen to us wherever you get your podcasts and at thirdpodfromthesun.com.

Shane Hanlon: All right. Thanks all and we’ll see you next time.