What’s It Like Pretending to Live on Mars?

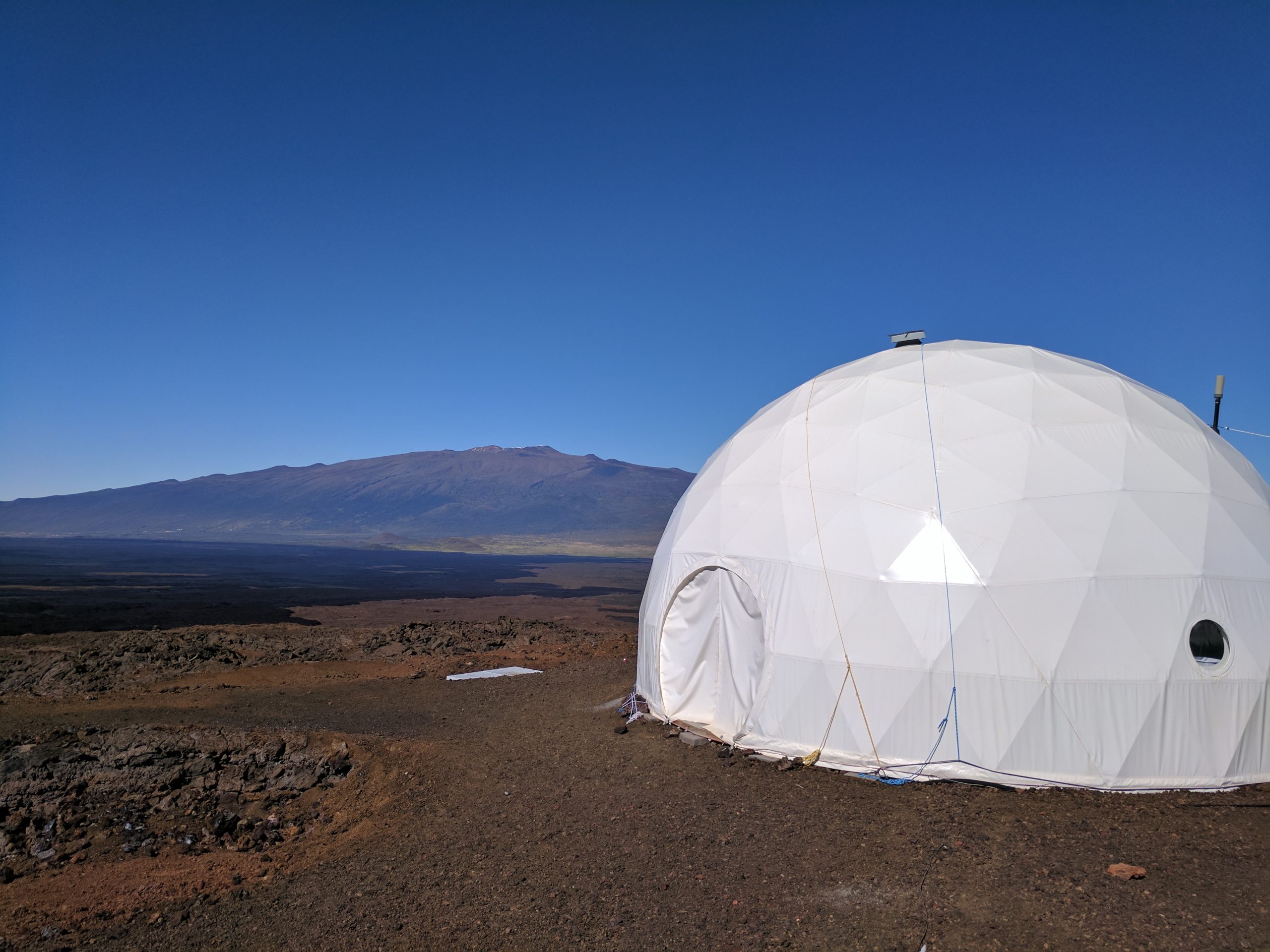

Biosphere dome at HI-SEAS. Credit: University of Hawai’i News, CC BY-NC-ND 2.0

If someone offered you the chance to drop everything, fly to Hawaii, and spend four months trapped in a dome with seven strangers in the name of science, would you do it? For writer Kate Greene, the answer to that question was a resounding “yes.” Greene was one of eight people selected to crew the very first HI-SEAS Mars analogue mission in 2013. In her recent book Once Upon a Time I Lived on Mars, she looked back on that time and what it taught her about the psychological challenges of long-haul space travel.

For decades, NASA has been running simulations on Earth to prepare astronauts for their time in space. But the six HI-SEAS missions taking place between 2013 and 2018 represented a shift in thinking towards the logistics of journeying to the red planet. The very first mission focused on something we all spend a lot of time thinking about: food. Greene’s crew spent four months in a habitat on the side of Hawaii’s Mauna Loa Volcano, tasked with chronicling their relationship to food over time to better understand a phenomenon called “menu fatigue.” They noted down what they craved, what they grew bored with, and what might keep them interested in their meals. Later missions lasted even longer, and focused on team cohesion, communication, and cooperation.

These simulated missions highlight the inherent contradiction in what NASA looks for in long-haul astronaut candidates, says Greene. They need someone who doesn’t bore easily, who gets along well with others, who is averse to drama and risk-taking yet willing to jet off to another planet.

Greene knew going in that she’d be living in cramped quarters with people she barely knew. She knew that she’d be limited to a small selection of shelf-stable and rehydrated “instant” meals. But the mission also affected Greene in ways she didn’t expect, forcing her to challenge her own preconceived notions about herself.

In this episode of AGU’s podcast Third Pod from the Sun, AGU chatted with Greene about the qualities NASA might look for in a Mars-bound astronaut, what she packed for Mars, what she missed during her time in the dome, and how her experience compared to the isolation of our pandemic year.

This episode was produced by Rachel Fritts (@rachel_fritts) and mixed by Kayla Surrey.

Transcript

Shane Hanlon: 00:00 Hi, Nanci.

Nanci Bompey: 00:01 Hi, Shane.

Shane Hanlon: 00:02 How are you?

Nanci Bompey: 00:02 I’m good. How are you?

Shane Hanlon: 00:05 I’m good. So, today I wanted to ask you, has there ever been a situation where you’ve been cut off, cut off from contact with folks, cut off from civilization? Something like that?

Nanci Bompey: 00:15 Well, I had this scary situation actually happened to me. Yeah. I was home alone in my mom’s house, I think it was after graduate school. I was living at her house for a little while.

Shane Hanlon: 00:30 Okay.

Nanci Bompey: 00:30 And she was away for the weekend and I went into the bathroom … Did I tell you this story already? I don’t know.

Shane Hanlon: 00:30 No.

Nanci Bompey: 00:36 I went into the bathroom and on the first floor, which is like a powder room. No windows. Okay?

Shane Hanlon: 00:36 Okay.

Nanci Bompey: 00:43 With no phone, no nothing, closed-

Shane Hanlon: 00:46 Who has a phone in their bathroom?

Nanci Bompey: 00:46 No, no, like I didn’t bring my cell phone in. I didn’t bring my cellphone in.

Shane Hanlon: 00:46 Okay.

Nanci Bompey: 00:50 It’s just a toilet and the sink.

Shane Hanlon: 00:53 Sure.

Nanci Bompey: 00:53 Close the door. Okay. I don’t know why I did that because I was home alone. Whatever.

Shane Hanlon: 00:57 Habit.

Nanci Bompey: 00:57 Anyway, closed the door and I was locked in the bathroom.

Shane Hanlon: 01:02 No. How?

Nanci Bompey: 01:02 It was so scary.

Shane Hanlon: 01:06 How does that happen?

Nanci Bompey: 01:07 Because my mom neglected to tell me that the lock was broken.

Shane Hanlon: 01:12 Oh.

Nanci Bompey: 01:13 So, I was like banging my body against the door, trying to get out. Hours. Luckily they were coming home that day.

Shane Hanlon: 01:20 Hours?

Nanci Bompey: 01:21 They came home that day and they actually had to take the door off the hinges to get me out. I was like [crosstalk 00:01:27].

Shane Hanlon: 01:27 So, what? Like three hours? What are we talking here?

Nanci Bompey: 01:29 Hours. A few hours.

Shane Hanlon: 01:31 Oh, that’s wild.

Nanci Bompey: 01:31 Yeah. I was banging my body at the door trying to get it open. But then I was like, well, I have water.

Shane Hanlon: 01:38 And you have a toilet.

Nanci Bompey: 01:38 I have a toilet.

Shane Hanlon: 01:40 Right. I mean, if you have to get stuck anywhere.

Nanci Bompey: 01:43 I’m not going to die, I guess.

Shane Hanlon: 01:44 Right. Oh my gosh.

Nanci Bompey: 01:45 Oh my God-

Shane Hanlon: 01:45 That is-

Nanci Bompey: 01:47 I don’t know if that counts as this isolation story, but I was cut off.

Shane Hanlon: 01:50 You were definitely cut off.

Nanci Bompey: 01:51 It was scary and now I don’t fully shut the doors on bathrooms anymore. I was just traumatized.

Shane Hanlon: 02:00 Oh my gosh, that such an interesting tidbit. I’ll have to remember that after we can actually see each other in person and hang out in person again. Next time you come over to my house, just to have a wide berth for the bathroom because [crosstalk 00:02:14] a little sliver of light.

Nanci Bompey: 02:15 Right.

Shane Hanlon: 02:18 Welcome to the American Geophysical Union’s podcast about the scientists and the methods behind the science. These are the stories you won’t read in the manuscript or hear in a lecture. I’m Shane Hanlon …

Nanci Bompey: 02:27 And I’m Nanci Bompey.

Shane Hanlon: 02:29 And this is Third Pod from the Sun. Okay, Nanci, so as usual, I didn’t just ask you something to learn more about you, which I do enjoy, but there is some tie into our episode today, right?

Nanci Bompey: 02:48 Yes. This story is all about isolation. So, we’re going to bring in our producer, Rachel. Hi, Rachel.

Rachel Fritts: 02:55 Hi, Nanci.

Nanci Bompey: 02:56 Yeah. Tell us a little bit about who we’re going to hear from today.

Rachel Fritts: 03:00 Yeah. So, NASA does these things called Mars Analog Missions where they’re really trying to simulate these long haul missions. So, what they’re trying to understand with these things is really the psychological impact of isolation and of really feeling cut off from Earth. So, what they do is they put groups of people for an extended period of time, for months at a time in this geodesic dome on the side of a volcano, on the Island of Hawaii. And they monitor how these people respond to being in this really isolated environment. And so, I was actually able to speak to a crew member on one of these missions.

Kate Greene: 04:03 My name is Kate Greene. I’m the author of Once Upon a Time I Lived on Mars. In 2013, I was a crew writer and second in command for NASA’s HI-SEAS mission, a simulated Mars mission designed to study the psychological, sociological effects of isolation as it might be on a Mars mission. An Analog Mission is a simulation of a space mission and these have been around for a while. When astronauts do space walks on the space station, for repairs or whatever, those are actually simulated before the astronaut even gets to space, in a giant pool of water and in Houston.

Kim Binsted: 04:58 The great big pool that we use to train the astronauts on how to do spacewalks. We’ll actually put them inside spacesuits and put them down in the water and the benefit of the water is it gives them the ability to be neutrally buoyant and allow them to kind of practice what it’s like actually being in space and without in a microgravity environment.

Kate Greene: 05:19 And so in a way that is an Analog Mission, you’re simulating a component of the space mission that you’re going on and it’s underwater because that simulates low gravity. So when scientists and engineers think about sending people on longer missions, further away from earth, like to the moon or Mars, they start to ask more questions about what that’s actually going to be like.

And so within the past decade or so, although it stretches back much longer, but it’s really picked up in the past decade, this idea of long duration simulated missions has become more popular, more interesting, and maybe more pressing because more people are talking about going to Mars. HI-SEAS and other long duration missions are looking at how groups of people work together to complete their mission far away from earth in an isolated environment. And so, Kim Binsted, the founder of HI-SEAS has said that if the human component, the psychological component of a space mission fails, it could be as disastrous as if a rocket explodes.

Kim Binsted: 06:22 So, essentially how do crew work together and how do they maintain a high level of performance as they’re doing these exploration tasks? Because if the crews start to not get along, that performance is going to go down. So, we need to understand how they continue to work together and how they can improve their end performance.

Kate Greene: 06:40 So, we need to really understand what goes into that. And so of course, it becomes critical, who do you pick and what kind of personalities do those people have? They were looking for people with thick skin, a long fuse and an optimistic outlook. And if you put those kinds of people together, generally, you’re going to get a pretty boring group of people, but that’s actually what you want on a long space mission. You do not want drama. You don’t want something like Big Brother game show. You don’t want the Real World. You don’t want any of that because there are so many things that could possibly go wrong and you want to try to minimize that.

So, I mean, as much as a lot of people will think that this would be an exciting adventure, you’re probably best suited to get people who are really even keeled and aren’t looking for a lot of drama. Of course, the first NASA astronauts were test pilots and the personality of a test pilot is someone who is absolutely willing to strap into a rocket, strap themselves onto a missile essentially, and drive it. And so, that kind of personality, that’s somewhat adventure seeking. There’s a lot of ego involved in that, but I do truly believe that a long mission to Mars, it’s like what, two and a half years? In some scenarios it’s projected, it could be that long, requires a very different kind of personality.

Someone who can deal well with boredom and monotony, someone, like I said, who isn’t into drama, someone who doesn’t need excitement and adventure, although it seems kind of antithetical to be some of the first people to step foot on an alien planet and not be adventure seeking. So, what kind of person is that? Honestly, I don’t really know.

Shane Hanlon: 08:26 All right. Before we go further, I need to back up for a sec. How did Kate get here? How does this opportunity just arise for someone?

Rachel Fritts: 08:36 Yeah, so it’s an interesting story actually. She was just reading an NPR article that caught her eye about why astronauts love Tabasco sauce. And she was obviously interested in this and read to the very end of the article and at the end, there was actually a call for applications for the very first HI-SEAS mission. And Kate decided, well, she had this childhood dream of being an astronaut. She knew that she would never be a real astronaut, but she could at least kind of live out her dream by applying for this thing. And she totally did not think that she was going to get it. And then, of course, she found herself packing for Mars.

Nanci Bompey: 09:30 That is crazy. So what does one pack when they go into the Mars, Analog, whatever you want to call it, on the side of the mountain?

Kate Greene: 09:40 Yeah. The packing for Mars question. What did we pack? I like this question a lot, because what we packed is not at all what real astronauts would pack on a Mars mission. Some of us brought pretty heavy boxes of things. One of my crew mates had a room full of objects. I mean, just like comfort objects, like a lap desk or a big puffy comforter and lots of trinkets and pictures. And that just, that wouldn’t fly, literally, on a space mission. I also brought a cardboard box full of actual physical books, thinking that, if I’m in this environment, I want to have something tactile that I can hold. That I can feel its weight, that sort of thing. Because we didn’t simulate lived gravity. That’s not the thing.

And besides, when you’re on Mars, you have a third of Earth’s gravity anyway. So, you’re going to be dealing with some gravity. You’re going to be getting used to some sort of downward tug. So, we brought our individual items and we all had our rooms, which were about the size of large closets. So, rearranged those rooms, however you want. But then most of the space was communal space and a lot of the objects in those spaces were shared objects. I mean, there was a laboratory and I didn’t work in the lab. We had a chief scientist and so, that was basically her space. We all had work tables that we could sit at. The question of shared communal versus individual really became interesting though, as the mission wore on and mostly in terms of food.

Rachel Fritts: 11:10 And actually this whole mission was inspired by the question of food.

Kate Greene: 11:16 The thing that actually launched this first HI-SEAS mission was the question of menu fatigue and that relates to the Tabasco sauce question that I was reading about in the NPR article many years ago, when I first learned about HI-SEAS and the possibility to be an Analog astronaut. The problem with menu fatigue is, this is a documented issue with astronauts on the space station who are up there for like six months. And over the course of the six months, NASA knows that they tend to take in fewer calories. Well, that’s not great because that means that they’re more at risk for injury and illness. And so if you think about that, that’s just six months, but if you have a mission that, it takes you eight months to get to Mars and then you’re on Mars with gravity again, I mean a broken bone, or if somebody gets seriously ill because they’re just not eating enough, then that is something that NASA really doesn’t want to happen.

It wants to understand better the question of astronaut appetite. So some of the issues that might be causing it are the fact that in low gravity, your fluids shift. And so, that means that maybe you have a clogged up nose, your sense of smell isn’t as good. And so, you just become less interested in food and that’s why Tabasco sauce or spicy things might be good and interesting because it’s some sort of culinary pow. You’re not getting it from the flavor itself, you’re getting it from the spice.

Speaker 6: 12:38 Eating in space is like eating with a head cold. You just can’t taste very much so because of this, a lot of our food tastes kind of bland. That’s why we like especially spicy food here, stuff that you might not normally eat on earth, like shrimp cocktail with horseradish sauce. That’s probably my all time favorite because it has a real bite and actually decongests your sinuses a little bit.

Kate Greene: 13:04 And so, maybe that’s why astronauts like Tabasco sauce. Could also be just generalized boredom, sort of this low level boredom they don’t really know about. And by the way, astronauts are loath to admit that they’re bored. Boredom is a big question for astronauts on long missions because the problems with being bored are that you’re less attuned to your environment. So, you might not notice something that’s actually dangerous or you might not realize how dangerous something is, if something’s going wrong. Something else that boredom can cause is a sort of sensation seeking behavior, which could lead to negative effects of maybe starting a fight. Just looking for drama. Just something, some sensation that you haven’t been getting because you’re bored. But really, the biggest problem with astronaut boredom is the fact that astronauts don’t admit that they’re bored and they may very well not be bored because it’s a very important job.

They take it seriously. They’re very good at what they do. That said, the environment that they’re in is extremely static. And even if you’re busy, you can still feel boredom when an environment doesn’t change very much. So, you have a changing routine, sure, but there’s still a sameness that can kind of creep in. Astronauts don’t talk about boredom because if they were to talk about boredom, then they would surely not be invited back to a mission afterwards.

So, one of the things that was interesting about our mission is that we talked about that a little bit more, but I have to say even halfway through the mission, we agreed, we weren’t bored. And I think we had assumed something of the astronaut attitude of, of course we’re not bored and this is all interesting and we’re doing this for NASA and this is great and wonderful. But for me … and I’ve always been a person who says that I’m not bored. I could sit in the most boring lecture that other people are so bored by and find anything interesting about it or do nothing for days on it and say, “No, I was thinking very interesting thoughts of course, I’m not bored,” but I did realize on HI-SEAS that I do have some sort of boredom threshold.

Nanci Bompey: 15:18 That’s so interesting that she felt like … I mean, really, I guess, it drove her to boredom on some level.

Shane Hanlon: 15:25 Yeah. And I imagine there’s all this interesting stuff going on in inside the dome and everything’s probably exciting, but I imagine there has to be stuff on the outside too, that she was missing.

Kate Greene: 15:39 Well, I definitely missed people. I missed behaviors and I’m finding this to be the case in quarantine. I miss being able to get on my bike and ride down the street and meet a friend at a beer garden. I miss drinking beer with friends. The thing that surprised me the most, that I didn’t realize I would miss as much, is swimming or just being submerged in water in some way or another. We had minimal showers, eight minutes of shower time a week that we all just kind of learned that we didn’t really even need. So we all took four minutes of shower time a week because limited water resources. You don’t want to use too much. Right? Because we were off grid. And I realized that I missed it, I missed swimming so much when I got an email from some swim instruction newsletter that I had signed up for years ago.

And it showed a picture of someone swimming, click on the link and you can watch this video. So, I was able to download this video at that time and watch this video of someone swimming and watching someone swim is almost the most boring thing that you can do. But I watched the whole thing and was riveted and just felt the feeling of swimming in water and I missed it so much. So, that was the thing that surprised me the most was how I could be riveted by a swimming video and really, truly miss swimming because at the time I was swimming quite a lot and I kind of quit cold turkey, but in the days after the mission ended, I definitely threw myself into the ocean and swam for as far as it could go and then turned around and came back. So, I was really happy that when the mission was over, I had Earth to come back to and not dry, rocky Mars.

Rachel Fritts: 17:37 Yeah. What were some of the other things you did when you got out? What were some of your priorities, as soon as you were out of the dome, off the volcano and kind of rejoining society?

Kate Greene: 17:54 Rejoining society looked a lot like drinking a beer and going to a party that celebrated the mission, which was really fun. Eating good, fresh food, and in particular vegetables and fruits that crunched in your mouth because the only vegetables and fruits that we had were dried fruits or rehydrated vegetables, and those are just necessarily mushy. So, we were always eating mushy vegetables. And it was an interesting thing that I’m remembering now is we would make these sandwich wraps that contained vegetables of some kind, and mayonnaise or whatever sauces or whatever you put on, condiments that you put on. But it was really important to us to put cashews or other nuts in these wraps so that we had just a different texture. So for me, I wanted more texture.

I wanted more sense experience in my food and that’s what you get when you crunch a carrot in your mouth or you eat a chunk of pineapple that has such a diversity of sensations in it. The fiber, the way the fibers pull apart and the very particular sweetness of fresh pineapple. Wow. Yeah. So, all of that was really great. That was like in the first few days. I was nervous about the sun because I’m a fairly pale person and Hawaii sun can be pretty strong. So I wore sunscreen, but I really … I got kind of pale over the four months and I think it didn’t look that great. There’s a pallor that wasn’t that good for me.

And I saw my crew mates gloriously tanning and so, I just was like, you know what, I’m just going to bite the bullet and I stood outside for 15 minutes and then got sunburned, and then that was over with. But yeah, missing the sun, even though it’s a little bit dangerous for me, I definitely missed that and was excited to experience that. That and ocean swimming and seeing people and having weird social interactions when people start going back to a more, I wouldn’t say normal, but whatever sort of social life they experienced before the pandemic era, I think that it’s kind of underappreciated that it’s going to be weird and people are going to be strange with each other, and strange with themselves.

Shane Hanlon: 20:18 The thing I’m thinking this entire time hearing this story is how it compares to our current situation. It’s isolation, isolation. And so, I am just stuck wondering, did her experience in the dome prepare her maybe uniquely for our current situation, where many of us are alone and isolated in a different way?

Kate Greene: 20:40 I mean, it’s hard to do a direct comparison, but there were some similarities in just that your world shrinks to a space, a smaller space and an environment where there isn’t a lot else going on. Your day-to-day starts to look the same over time. And so, I knew that was going to happen again for me, and I thought about what I wanted to do. I started with food, to be honest, I started late in February going on grocery runs. I live in New York City and so I couldn’t go for one big grocery run, but I started doing smaller grocery runs and getting shelf stable ingredients that I knew could last me through because we didn’t know what it would be like. I didn’t know how supply chains would withstand the shock. So, it was making sure that I could have enough food and water that could get me through right [inaudible 00:21:31].

I even got some of the same foods that I really appreciated while on Mars. I got some spam, for spam the soupy, and I got some other things that made … I got some powdered eggs just in case, so I could make these omelets that I discovered I really loved on Mars. And I found that to be a great comfort, honestly. So, I had some comfort foods from that experience that I could choose from because honestly the HI-SEAS mission was … I have great memories from it. And so, I kind of fell back into that. I also, I did things that weren’t there for me on the mission, but I anticipated, I would appreciate. And I mean, everyone talks about what their panic purchases were, but I panic purchased houseplants. I didn’t have a lot of houseplants before, but something about seeing these green plants and knowing that I was going to be stuck in a room with them, I live in a studio apartment, that I thought I need to have something, something to nurture and care for and watch grow.

And I was really glad that I had that. There are so many people who were living with families and that’s such an experience and so different in so many ways. There are people who had to change their living situations throughout the pandemic. So, speaking from my experience, I also realized that being with five other people relieved a huge burden. There’s something really, really hard about being by yourself. So, like figuring out how to do … As the pandemic wore on, more social things like in-person and what was safe and all that, was actually super critical to me. But in the first couple months, that was a big question and I realized just being by yourself is a lot different than being isolated with five other people, and that I’m definitely a person who does quite well, better isolated with people than I am isolated by myself. So, that was something that I learned, that it was a huge difference between the Mars experience and this quarantine experience.

Nanci Bompey: 23:32 That’s so interesting, that her quarantine experience now is in some ways, I guess, more difficult than it was doing the HI-SEAS mission.

Rachel Fritts: 23:42 Yeah. That was really interesting to hear about from her very unique perspective.

Nanci Bompey: 23:49 Yeah. I mean, there’s only a few people who have that unique perspective on it. And I wonder, given her experience, if she’d actually go on … If there was the opportunity to go on a real mission to Mars.

Kate Greene: 24:01 I think that a mission to Mars would be extremely difficult, will be extremely difficult and very exciting, and really monumental for humanity. But I don’t know, I think that there just … In the mission itself, there will still be so many unanswered questions. So yeah, that’s what I think this mission, this simulated mission revealed to me, that you can ask as many questions as you want and think yourself into the tightest design that you can, but you’re not going to know everything. And you kind of have to make sure that there’s something built into the mission that can withstand that unknowability enough, so that there’s a hope that the whole thing succeeds.

Rachel Fritts: 24:01 Would you do it again if you had the chance?

Kate Greene: 25:10 Would I do a simulated Mars mission again? I don’t think I need to do a simulated Mars mission again.

Rachel Fritts: 25:18 Would you go to Mars if you were given the chance?

Kate Greene: 25:24 Well, I think it’s highly unlikely that I would ever go to Mars, that I would ever be chosen to go to Mars and participate in any sort of actual Mars mission. It would definitely depend on the context, the scenario. I think I would want to know a lot about what went into the mission and I would want to … and probably annoyingly, be an active participant in a lot of the design of the mission.

So, with all of that information out in the world, I don’t think that I would be one chosen to participate in a Mars mission. I wouldn’t mind at all going to the moon. I think that, that’s nice. It’s not so far. It would be extremely exciting. The moon is such a destination in so many people’s hearts and minds, I just feel like that would be a trip.

Shane Hanlon: 26:19 Okay. So, we’re not going to talk about going to Mars or going to the moon, but poll for the group, who among us would volunteer to do something like HI-SEAS, and being in the dome for X amount of time, cut off from people? I’m a no.

Nanci Bompey: 26:39 I’d do it. I’d totally do it.

Shane Hanlon: 26:40 What’s your time limit?

Nanci Bompey: 26:42 Wait, what’d she do, four months, Rachel?

Rachel Fritts: 26:45 Yep. Four months.

Nanci Bompey: 26:46 I could do that.

Shane Hanlon: 26:46 You’d do four months? All right.

Nanci Bompey: 26:46 Yeah.

Shane Hanlon: 26:48 All right. What about you, Rachel?

Nanci Bompey: 26:49 Rachel?

Rachel Fritts: 26:51 No.

Nanci Bompey: 26:51 It’s funny because, I mean, you guys know me. I’m an outgoing person, but I’m like yeah, I could hunker down there.

Shane Hanlon: 27:00 You’d be one of the experimental variables in it.

Nanci Bompey: 27:03 I could drive everyone crazy.

Shane Hanlon: 27:07 I know.

Nanci Bompey: 27:08 Yeah.

Shane Hanlon: 27:08 Oh man. All right. Well, that’s all from Third Pod from the Sun.

Nanci Bompey: 27:14 Thanks so much to Rachel for bringing us this episode and of course, to Kate for sharing her work with us.

Shane Hanlon: 27:20 This episode was produced by Rachel and thanks to our sound engineer, Kayla Surrey.

Nanci Bompey: 27:25 Hey, check us out on your favorite podcasting app.

Shane Hanlon: 27:29 Yes.

Nanci Bompey: 27:29 Please rate and review us on Apple Podcasts and you can always find us at thirdpodfromthesun.com.

Shane Hanlon: 27:35 Thanks all, and we’ll see you next time.