22-Storied careers: Ocean sensors and dog scenters

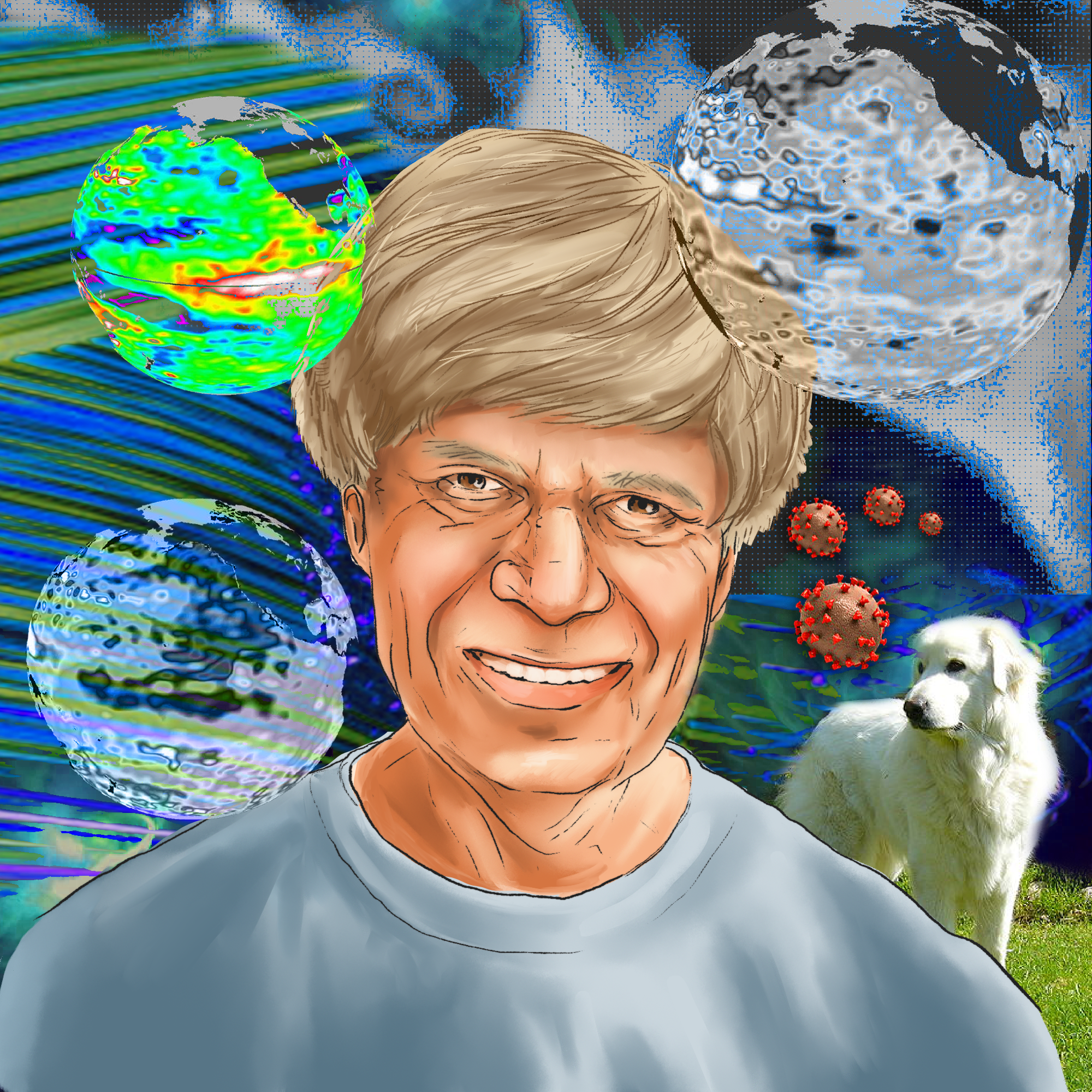

Tommy Dickey is an emeritus oceanographer from U.C. Santa Barbara and Naval Operations Chair in Ocean Sciences. His modeling and observational research yielded ocean monitoring technologies and tools. For retirement, Tommy trains and deploys Great Pyrenees as therapy dogs, while studying scent dogs’ capacity to detect COVID-19. We talked with Tommy about his path from a rural childhood to a career dedicated to oceans.

Tommy Dickey is an emeritus oceanographer from U.C. Santa Barbara and Naval Operations Chair in Ocean Sciences. His modeling and observational research yielded ocean monitoring technologies and tools. For retirement, Tommy trains and deploys Great Pyrenees as therapy dogs, while studying scent dogs’ capacity to detect COVID-19. We talked with Tommy about his path from a rural childhood to a career dedicated to oceans.

This episode was produced by Devin Reese and mixed by Collin Warren. Illustration by Jace Steiner.

Transcript

Shane Hanlon: 00:00 Hi Vicky.

Vicky Thompson: 00:01 Hi Shane.

Shane Hanlon: 00:02 What are some of the weirdest jobs you’ve ever had that have nothing to do with where you are today, like doing what you do at AGU, or even on this podcast?

Vicky Thompson: 00:10 Okay, I have a list.

Shane Hanlon: 00:13 Is this a chronological list? What was your first job?

Vicky Thompson: 00:17 Yeah. My first job I ran a snack bar and I planned and ran roller skating birthday parties for children.

Shane Hanlon: 00:26 Okay. Okay.

Vicky Thompson: 00:26 Yeah.

Shane Hanlon: 00:28 Sorry. Okay. Then what’s your list?

Vicky Thompson: 00:29 Okay, so my list, so that. So those things. I was a travel planner for Rider, and I think I actually ghosted that job, which is terrible.

Shane Hanlon: 00:41 Oh, I see.

Vicky Thompson: 00:41 I was a telemarketer.

Shane Hanlon: 00:42 You arranged their travel.

Vicky Thompson: 00:43 Yeah. I arranged-

Shane Hanlon: 00:43 You were a telemarketer?

Vicky Thompson: 00:45 I was a telemarketer.

Shane Hanlon: 00:46 Can you say for whom? You shouldn’t say for whom. Disregard. Keep going.

Vicky Thompson: 00:49 Oh, for all sorts of people. I mean, it’s like contracts-

Shane Hanlon: 00:51 Oh, okay. You were just a telemarketing company-

Vicky Thompson: 00:53 Oh, yeah. I would just go into the little telemarketing office and they’d feed me my script, and I would dial phones and try to get people to stay on the phone and take surveys-

Shane Hanlon: 01:03 Oh my goodness, Vicky.

Vicky Thompson: 01:03 … and listen to me talk about things. I guess that’s kind of related to this.

Shane Hanlon: 01:07 I was going to say, you are describing my nightmare. Just talking on the phone. I hate talking on the phone.

Vicky Thompson: 01:13 Oh, I love it.

Shane Hanlon: 01:13 Oh my goodness.

Vicky Thompson: 01:13 I’m so curious about everybody. I was a nanny.

Shane Hanlon: 01:17 Okay.

Vicky Thompson: 01:20 I guess I could say I was a bus driver for a short time in college.

Shane Hanlon: 01:24 What’s the, “I guess” part of that?

Vicky Thompson: 01:26 Well, so I drove volunteers around in a very, very, very large band, and I had to make my little stop and get them to where they were going.

Shane Hanlon: 01:34 Did it have a bus door?

Vicky Thompson: 01:34 No, no. It was a van. I did get pulled over by the cops once, in my van. But anyway, so-

Shane Hanlon: 01:44 All right.

Vicky Thompson: 01:44 Let’s not talk about that.

Shane Hanlon: 01:45 No, no, no. We won’t. We don’t have to incriminate you. That’s quite the background.

Vicky Thompson: 01:53 I had one that I wanted to do, but I think they never took my job application seriously. I applied to be a Zamboni driver.

Shane Hanlon: 02:01 Oh my gosh.

Vicky Thompson: 02:02 Yeah.

Shane Hanlon: 02:03 That would be so amazing. I would’ve absolutely loved that.

Vicky Thompson: 02:06 I just walked into the ice skating rink and I was like, “I saw your sign. That sounds cool.”

Shane Hanlon: 02:10 Oh my gosh.

Vicky Thompson: 02:11 And they … No.

Shane Hanlon: 02:13 Oh, if only. Your life could be so different now, Vicky.

Vicky Thompson: 02:15 I know. I could have been a Zamboni driver.

Shane Hanlon: 02:22 Oh, man.

Vicky Thompson: 02:22 What about you?

Shane Hanlon: 02:22 This is going to be quick because I haven’t had nearly that many jobs.

Vicky Thompson: 02:25 Oh.

Shane Hanlon: 02:25 Mainly because … So I did. Sike. I worked as a caterer for a little bit. It was a real party down atmosphere and I worked-

Vicky Thompson: 02:33 Did you have a vest?

Shane Hanlon: 02:35 No. This is in real Pennsylvania. We did not dress up.

Vicky Thompson: 02:38 Okay.

Shane Hanlon: 02:38 I worked in a pizza shop for a while. At one point, I could actually make a pretty mean pizza. I can’t anymore. It was a long time ago. But the thing I did for the longest was I grew up in a country and I worked on a ranch as, essentially, the groundskeeper from before I probably should have until halfway through college.

Vicky Thompson: 03:02 You were a child?

Shane Hanlon: 03:02 Yeah.

Vicky Thompson: 03:03 So what were some of your roles as a groundskeeper?

Shane Hanlon: 03:07 I did a lot of mowing and weed whacking, if I’m being honest.

Vicky Thompson: 03:10 Weed whacking is fun.

Shane Hanlon: 03:11 It really is.

Vicky Thompson: 03:12 Yes.

Shane Hanlon: 03:12 I was just responsible for fixing stuff that broke down, mending fences. I didn’t take care of the horses at all, actually. It’s funny, it was a horse farm. It was a ranch.

Vicky Thompson: 03:21 Mending fences.

Shane Hanlon: 03:22 I didn’t touch the horses. I didn’t even like the horses. They were not my friends. But yeah, I had all three of my brothers, too, had this job. It was friends of the family, before me. Yeah. I was the second most liked of the four brothers throughout the process.

Vicky Thompson: 03:39 But you were still like a legacy hire.

Shane Hanlon: 03:42 I was the legacy hire. I was the last of four.

Vicky Thompson: 03:46 I guess we got to let him do it, too.

Shane Hanlon: 03:47 Yeah. Yeah. So the good old days of working on a ranch in rural Pennsylvania.

Vicky Thompson: 03:53 Oh, that sounds fun.

Shane Hanlon: 03:59 Science is fascinating, but don’t just take my word for it. Join us as we hear stories from scientists for everyone. I’m Shane Hanlon.

Vicky Thompson: 04:08 And I’m Vicky Thompson.

Shane Hanlon: 04:10 And is this Third Pod from the Sun. So Vicky, you never know where your professional path might lead.

Vicky Thompson: 04:23 Yeah, I guess, or where it doesn’t.

Shane Hanlon: 04:23 Oh my gosh. Okay. We didn’t have time for this, and we do this all the time. So there’ll be time for this later. But someday I will talk about my, I have to say former, hatred of plants. And this comes about from a professional setting. But today, because we have no time for that, we’re going to talk about, or excuse me, we’re going to chat with someone who grew up in Indiana and first dreamed of being a farmer, but ultimately became an oceanographer.

Vicky Thompson: 04:53 Wow. That’s like someone who grows up in Alaska and becomes a tropical forest biologist.

Shane Hanlon: 04:58 I know. It’s pretty wild. I was wondering, how does someone living in landlocked Indiana get interested in ocean science? And so to answer that, I’m going to bring in producer Devin Reese. Hi, Devin.

Devin Reese: 05:11 Hey, Shane. I’m pleased to be here to delve into that very question.

Vicky Thompson: 05:17 So Devin, why is Shane musing about career trajectories today?

Devin Reese: 05:22 Well, maybe he’s having a midlife crisis.

Vicky Thompson: 05:24 Oh.

Devin Reese: 05:25 No, I think it’s because we’re going to talk with an oceanographer today who has this fascinating background and who I discovered when I interviewed him that even in retirement, he’s still got that research mind. He’s still asking questions and doing research.

Shane Hanlon: 05:44 I mean, midlife crisis aside, that’s something we can all aspire to, right?

Devin Reese: 05:50 Yep. I agree. It was really inspiring to talk with the oceanographer. His name is Tommy Dickey, and basically thanks to some mentors along the way and his own personality, a real stick-to-it personality, he went from that small farming town to become a PhD researcher. He’s in Ocean Sciences at the University of California, Santa Barbara.

Shane Hanlon: 06:13 Great. Let’s hear it.

Tommy Dickey: 06:18 Good morning. First of all, thanks for inviting me to do this podcast for you. As a way of introduction, I am a distinguished Professor Emeritus and a Secretary of the Navy, Chief of Naval Operations Chair in Ocean Sciences at the University of California, Santa Barbara.

Devin Reese: 06:41 That’s a long title. Could you explain this designation as the Chief of Naval Operations Chair in Ocean Sciences? What does that mean?

Tommy Dickey: 06:51 I was named a Navy chair in 2008, making me one of 12 distinguished Navy chairs. And the program began in 1984 with some of the original recipients of this award being Bob Ballard of Titanic fame, and Walter Munk, possibly likely the most important oceanographer of the 20th century. So I was really, really fortunate to receive this honor, and I was the first one outside of strict physical oceanography to receive this honor, and I received it primarily because of my interdisciplinary work and my work in developing the field of bio-optics.

Devin Reese: 07:42 In reading about you, I really noticed the emphasis on the interdisciplinary aspects of your work.

Tommy Dickey: 07:50 Oceanography is pretty much done interdisciplinary for the early years, the challenger back in the 1880s, but then I guess I would say around 1950 or so, it became a very disciplinary science. And so physical oceanographers looked down on biological oceanographers and chemical oceanographers, and they didn’t really cooperate or collaborate that much. And I had always had interest in looking at the edges of things. And in this case, I was interested in the biophysical, bio-optical, bio-geochemical aspects. Well, I wasn’t trained in any of this, but I started doing experiments and talking to people. And from that, we developed programs which were interdisciplinary.

Devin Reese: 08:41 So where did your interest in looking at the edges of things by doing experiments start? I mean, didn’t you grow up on a farm?

Tommy Dickey: 08:50 To clarify a little bit, I didn’t really live on the farm, but I lived across the street, if you like, or adjacent to farms my entire life. So as a little boy, you always want to play with different kinds of things. So farm toys were a big deal to me, and the farmers who lived right next to my house, basically really, really nice guys. So I’m sure that the fact that they really enjoyed the kids, and one of them made kites for us. In fact, he became famous as The Kite Man. You can imagine this was back in probably in 1950s. And so I was endeared to these people, to tell you the truth. They were fantastic. So that inspired me to want to become a farmer like them, because I thought they were really cool.

Devin Reese: 09:56 So when did you start thinking about other options for yourself besides becoming a farmer?

Tommy Dickey: 10:02 We lived in this little town called Farmland, and then we moved to a little bit larger town. It was called Union City, and it was also small. And there, the fourth grade was a very important year of school for me in that I had a teacher who really took me under wings, and moving to a new town, and it wasn’t easy shifting, as you know, going from one school to another and a different population of students and a little bullying action going on there. So this teacher took me under her wing and she thought I had a lot of potential.

Tommy Dickey: 10:43 During that year, my father, who was working in a local factory and a nighttime sports writer, decided that he wanted me to go to one of the basketball games he was reporting on. So I went, and he said, “Okay, now how about instead of me writing the column, you write the column.” This is at 10 years old. So I said, “Well, okay. I know I’m going to need some help here.” He said, “Oh, I’ll help you.” We wrote the article and it got published in the local newspaper. My picture got in, which was very cool.

Tommy Dickey: 11:18 So at that point, I really became motivated to do something really good in my life, I suppose you would have to say. So I really started working hard to get straight A’s, do the best I could at school. And fortunately, I had some good teachers. So that launched me to go to Ohio University. And there, I received scholarships, basically paying my way because of my academic credentials, I suppose you would say. And so I studied physics and math.

Devin Reese: 11:53 Wow. So I have a couple questions. First of all, you grew up across from a farm and you said your father worked in a factory. So how did your parents respond to the incredible fact that by the end of high school you were so highly motivated that you went to college in physics? What was that like for them?

Tommy Dickey: 12:16 Well, I think my parents were really, really nice people. I think that at some time later on in my career, I think they were a little bit awed by where I was and what I was doing, and honestly didn’t fully understand what I was doing. But they knew it was good. They really wanted me to go to college. That was the main thing. But yeah, it was sometimes hard to communicate with them what I was really trying to achieve, but they were unbelievably supportive.

Tommy Dickey: 12:50 My brother and I were the first to go to college, and both of our parents really wanted us to go to college because my father, who was this sensational basketball player, was not able to go to college because of a physical problem. So I was selected to go to Argonne National Laboratory, then under the Atomic Energy Commission, for a summer program. So in that summer program, I learned what research was about. And so the work that I did was in plasma physics. And just for viewers who are not too familiar with plasma physics, it’s basically ionized gases, which make up 99% of the universe. So the interesting part of this is that our project was to minimize the formation of plasmas in the Zero Gradient Synchrotron at Argonne.

Devin Reese: 13:44 That’s quite amazing, really. I mean, just to look at what you’re doing now and then hear this story of where you started in pretty much a landlocked place. I mean, I guess you had the great lake. But, I mean, you grew up in a landlocked place, so I imagine that you could never have predicted the path that your life was going to take from there?

Tommy Dickey: 14:05 Absolutely not. I didn’t even know what an ocean was. I didn’t see the ocean until I graduated from college. So this transition from wanting to be a farmer to becoming an oceanographer is quite an amazing story. So one of my friends and I, I guess our last year in college, we decided that needed to see the ocean. And so we drove to Florida and drove around, and I was in awe, for sure.

Tommy Dickey: 14:45 The Vietnam War was raging and I was about to be drafted into the Army or Marines, and I didn’t really want to do that. So I found the Coast Guard, which is a humanitarian service, and I like to describe it as the only service which trains people to save lives. So I was taken by what that was about, and so I enlisted. I couldn’t go in as an officer for various reasons. So I enlisted for four years into the Coast Guard. And during that time, I taught electronics for the first three years, and then in the last year, my fourth year, we had racial strife on our Coast Guard base, which was off the tip of Manhattan, a place called Governor’s Island.

Tommy Dickey: 15:40 So I guess I had a good rapport with my students, and the commanding officer of the training center decided that he wanted to send a group of four of us to a race relation school in Patrick Air Force Base, Cocoa Beach, Florida. So it was six weeks, I believe, six to eight weeks, and I became a race relation instructor. This is the way the military works. So we did that, and then I came back to the base and I worked with another individual, and we basically did what we call rap sessions, and we basically got coast guards together and just let them vent and talk about what was going on.

Devin Reese: 16:31 By the time you were finishing in the Coast Guard, had you fallen in love with the ocean? Was it already becoming clear to you that you were going to work on oceans and ocean science?

Tommy Dickey: 16:42 Yeah, really good question. So as I indicated earlier, I was really interested in plasma physics. Well, plasma physics has basically a fluid component to it. And on our base, besides electronics education, there were marine science technicians who were being trained. And so I met some of these marine science technicians, especially during the last year. And I got fascinated, and I decided, “This is pretty interesting. I like this ocean atmosphere thing.” And about that time, a little bit earlier, Princeton University made a partnership with the National Oceanic and Atmospheric Administration to place a lab for numerical modeling of the atmosphere and the ocean. And this was on the Forrestal Campus at Princeton.

Tommy Dickey: 17:33 So it had just begun. I don’t think there were more than five or six students who preceded me in that program, but I have to go into some detail about the history of this lab because it’s pretty phenomenal. This lab began, actually, out of the Institute for Advanced Study in Princeton where Einstein finished his career, and Joseph Smagorinsky had been at the institute with John von Neumann, a very famous mathematician and computer guru of the time, with the beginning of computers. And they decided that a really important problem was to utilize these new large-scale computers, and ENIAC being the first one, really, out of the University of Pennsylvania, but in collaboration with people at the Institute for Advanced Study at Princeton. ENIAC had been used for ballistic trajectories and a few other odd things. But the people at the Institute for Advanced Study, including John Von Neumann and Jewel Charney and Joseph Smagorinsky, decided we could utilize that computer to do large-scale weather forecasting. And that was the beginning of the Geophysical Fluid Dynamics Lab and program at Princeton University.

Vicky Thompson: 19:09 That’s pretty amazing to think that computers were not always a part of weather forecasting.

Devin Reese: 19:14 Yeah, I agree. And that lab where Tommy got his PhD, that he used ENIAC, which is basically the first digital programmable computer, and it was developed secretly at UPenn for military purposes.

Shane Hanlon: 19:29 Yeah. I mean, it’s hard to imagine reliable weather forecasting on any scale, frankly, without collection and sharing of data from sensors via computers.

Devin Reese: 19:42 And that’s actually one thing Tommy pioneered was developing different types of sensors that could collect data remotely and then relay it through networks.

Vicky Thompson: 19:52 That’s a major transformation that he was part of, and it sounds like his research included atmospheres as well as oceans.

Devin Reese: 20:01 Tommy, how would you describe the focus as you got involved in the research at the Princeton Geophysical Fluid Dynamics Lab?

Tommy Dickey: 20:09 So it was basically dynamics and thermodynamics of the atmosphere coupled with an ocean model, and so the ocean is very important in all of this. One of the important people in that was Kirk Bryan, who is basically the father of all numerical models of the ocean. So it is an amazing collection of people, and so they brought in myself, and I think that my class had one other person. So I had classmates of six total in an environment of basically research. This was not traditional education. It was more of a Cambridge or Oxford style of mentoring. And I recall my thesis advisor saying, “Okay, here’s a great book on fluid mechanics. Go read that.” Well, this is a 500 page book written by George Batchelor.” He said, “When you get done with that, I want you to read this other book by George Batchelor on turbulence.”

Devin Reese: 21:13 Did you actually read both of those huge volumes, cover to cover?

Tommy Dickey: 21:16 I sure as heck did, a couple times. I wanted to get my PhD. I learned a lot. There’s a lot I don’t understand. But nonetheless, I certainly gave it a fighting chance. Now, as to courses, most of the work was really done on the campus through mentoring. So we would sit down with one of the professors, it could be Menabi, it could be Smagorinsky, all of that cast of characters who were … But they weren’t teachers. They were mentors.

Devin Reese: 21:49 At what point did the culture shock of coming from this really rural setting and going out into the world in such a grand way really … At what time did you settle into yourself in this unexpected identity?

Tommy Dickey: 22:05 This was culture shock, to say the least. So anyway, again, I’m a pretty persistent person. I guess you figured that out. So one way or the other, I was going to make it through this. So I ended up doing my thesis on turbulence, small-scale turbulence and internal gravity waves, which is basically motion of waves, which occur due to stratification in the ocean. Very fundamental problems. One of my mentoring classes, if you like, was with George Philander, who basically developed the first models of ENSO and the atmosphere interaction with the ocean. My assignment was one that he threw out there. “Here’s some ideas. See what you could do with it, and if you do well enough, we’ll pass you.”

Tommy Dickey: 22:57 So he threw out this problem of solving equations for equatorial waves. These are long waves. They’re like thousands of kilometer waves propagating across the Gulf of Guinea off of Africa. So he said, “That one might work for you. You want to try that?” I said, “Sure.” What a fool. Of course, he’s an equatorial wave guy, and he was probably interested in the solution to this problem. So he said, “Well, I don’t really expect you to solve it, but I want to see how far you can get.” I said, “That’s better.”

Tommy Dickey: 23:36 So I took this problem and I solved the equations on a computer, a very large computer. Princeton, incidentally, got the fastest computers on Earth for quite a long time. And so the fastest computer on Earth is sitting there. And so I wrote up some code, I worked out some solutions, and I actually solved the problem. And after I solved the problem, he said, “Hey, I’m surprised you were able to do that.” So that helped my ego. The ego meter went up. So he said, “Well, I think you should publish …” Yeah. So he said, “I think you should publish this in the Journal of Physical Oceanography.” So I said, “Well, that’s another step. It’s got to get through the review process. I am a total rookie at this.” So I wrote up the paper, it got published, amazingly, and that was my first published paper.

Devin Reese: 24:34 I almost get the image, as you talk about all this, of you on a roller coaster.

Tommy Dickey: 24:45 Good analogy.

Devin Reese: 24:46 I do.

Tommy Dickey: 24:47 Right. Highs, lows. So one day I put in my programs, and then we put them in on cards. This is way, way back when, when card readers. So I put it in, and so I go to pick out my output in the bin, and churn away with this big computer, and there’s a huge, huge stack of computer paper waiting for me. I say, “Oh my God, what have I done?” Well, I must have had an infinite do loop or something really bad in my code. So I could have been the person who brought down Princeton’s gigantic computer through my own ineptitude. But it was fun and just a great time there.

Devin Reese: 25:32 Yeah. I noticed in some of your writing in the paper that you talked about a transition from when the ocean was entirely sampled from ships to the transition to really being able to do remote things with buoys or satellites. Can you just tell me a little bit more about your positioning in that transition?

Tommy Dickey: 25:59 Sure, sure. Yeah. I guess you have to go back to a little bit of history as well in this, in that from 1950 through, I would say, maybe the early ’80s, there was a different thing going on with oceanography. Ships were dominating because we didn’t have autonomous samplers from buoys so much, drifters or whatever. So in that regard, the ocean was vastly under-sampled. In fact, Walter Munk described the 20th century as a century of under-sampling of the ocean. And that struck me that we needed to sample the ocean on the proper scales. This means anywhere from seconds on up to, if you want to get into climate, seasonal certainly, and then on up to climate scale, tens of years and more. So we needed to sample that in order to understand it, to be able to get input into models and also to test the models. Are these models working or not?

Tommy Dickey: 27:09 Well, I wasn’t trained in any of this, but I started doing experiments and talking to people, and from that, we developed programs which were interdisciplinary, studying the ocean on scales from seconds on up to decades using buoys, drifters, and, of course, satellites came into play. So I started developing instruments, bio-geochemical and bio-optical sensors that could be collecting data on the same time and space scales as the physics. So we developed this time-space diagram, which ranged from seconds on up to decades and from millimeters on out to global scale.

Tommy Dickey: 27:54 So we created this figure, if you like, or diagram. And Munk had one somewhat similar to that, but not as developed. And so we developed that diagram, and it became the beacon for people designing experiments. Ships certainly still played a role, but it also led to the development of autonomous underwater vehicles, profiling current meters with optical instruments that I worked on, all of these different things to fill in time space diagram. And so that’s where this whole thing went. And in a sense, it went viral.

Devin Reese: 28:35 So this diagram allowed you to see where the holes were and literally start developing instrumentation to fill in some of those gaps?

Tommy Dickey: 28:44 Absolutely. Yeah. That’s a nice way of putting it. And as Walter Munk commented, the gaps were humongous, basically. We’re not sampling what we should be sampling. And I was very interested in episodic events. And of course, ships can’t go into areas where there are hurricanes coming through, and they can’t be out there long enough to get the time series even very often to see a mesoscale eddie. And so the instruments that I developed with my colleagues were sampling down to seconds, minutes, and we started really discovering interesting things in terms of what happens when a hurricane moves through an area.

Tommy Dickey: 29:25 And so that became one of my favorites for quite some time in that we had moorings off of Bermuda, and hurricanes would go virtually right over the mooring. And when that happened, we got these dynamic responses, the mixed layer, upper layer of the ocean deepened. We had injection of nutrients coming into the aphotic layer, and then you’d see these big phytoplankton blooms. And this was earth shattering. People hadn’t seen this before, and it was done on time scales.

Devin Reese: 30:00 You have certainly had an interesting career, Tommy, and I know from your AGU perspective’s paper that your retirement is interesting, too, although your health forced you to retire.

Tommy Dickey: 30:22 Yeah, yeah. So anyway, I hated to have to retire. I took my dogs, my Great Pyrenees dogs to class with me, which made me, and especially my dogs, a big hit. And so I took my dogs to campus with me. And of course, the students love the dogs. And an outgrowth of that was that, at the same time, I was developing an interest in using them as therapy dogs. I had come across a good friend who suggested that after my dog, Teddy, had done very well in obedience class, that, “Why don’t you guys go ahead and get certified to be a therapy dog team?” So that began the whole therapy dog thing. So then in the course of time, I got more Pyrenees that I had adopted. And so we kept doing therapy dog work. We went to schools, colleges, hospitals, nursing homes, Special Olympics. We went all over, doing these therapy dog visits. And one of the places we ended up in the last, I guess about four years, was the California Science Center.

Tommy Dickey: 31:40 So of course, I had a nose around what other exhibits were going on besides ours, and one of the displays talked about dogs’ sense of smell. And so I thought, “This sounds cool,” because I’d been developing sensors for the ocean, bio-geochemical sensors, all kinds of sensors for some time. And I thought, “And here’s this dog that can smell way over 100 times better than a human being. Why can they do that and how can we utilize it?” I decided that I wanted to find out, could COVID be detected using these dogs and their sense of smell? So I started reading books on medical scent dogs, and I started digging deep into the literature, as I always do, and I found a few examples where people were training dogs on the COVID scent.

Tommy Dickey: 32:39 And one of the people I met was Heather Junqueira, who has a small research program down in Florida utilizing beagles to detect COVID and other things as well. And we had a long conversation. At the end of conversation, I said, “Would you mind writing a paper on COVID scent dogs with me?” She says, “Oh, sure. Let’s do that.” So we did. So the paper appeared in a Journal of Medicine, and then the most recognition I’ve ever received in my life was after that paper came out, and it became viral, we were contacted from people all over the world, journalists all over the world who wanted to learn about how dogs could be used to detect COVID. So Heather still does that with individual dogs. It has its small following. They’ve been used for Miami Heat basketball games, as an example and at several airports in Europe.

Devin Reese: 33:53 That’s so exciting. You’re such a researcher at heart. You can’t get away from it, right? You’ll be studying something else once you’re 99.

Tommy Dickey: 34:03 I’m a crazy researcher.

Shane Hanlon: 34:11 Vicky, do you think your … What’s your dog’s name? Ila?

Vicky Thompson: 34:17 Ila.

Shane Hanlon: 34:17 Ila. Do you think Isla could be a COVID detection dog?

Vicky Thompson: 34:19 No. No. She’s-

Shane Hanlon: 34:28 Absolutely not.

Vicky Thompson: 34:28 Absolutely not. No, she’s scared of everything, but also barks at everything.

Shane Hanlon: 34:31 She’d just be a bunch of false positives, essentially?

Vicky Thompson: 34:34 Yeah. Just whatever the signal would be, she would just immediately give it. She would just be too scared. Yeah, no, what about your dog?

Shane Hanlon: 34:44 Well, I mean, so my dog, Tacoma, whom I love very, very much, he’s actually a Pyrenees, like Tommy’s dogs. But honestly, this would just not be his jam. He doesn’t love tasks. To him, his job is to guard our yard from squirrels and a random set of hounds that walk by our house once in a while, get pets, and try to steal pizza.

Vicky Thompson: 35:06 Wait, get pets?

Shane Hanlon: 35:08 Oh, not like-

Vicky Thompson: 35:09 Oh, pets. Oh, pats. Like ear scratches.

Shane Hanlon: 35:11 Yeah. Pat is a better word, yes. But if you were to pet a dog, yes. He does not have success in going after this one set of dogs. No, he’s not trying to go after animals. He wants to be petted because he’s a big softie.

Vicky Thompson: 35:25 I thought he wanted his own pets.

Shane Hanlon: 35:29 He does have a plush hedgehog that makes this squeaky noise.

Vicky Thompson: 35:37 Oh, that must be annoying.

Shane Hanlon: 35:38 It’s actually adorable, but the thing is falling apart. And so who knows? I don’t actually know if we’re going to replace it when the time comes.

Vicky Thompson: 35:44 Oh, I feel like I just really revealed something about myself by immediately saying. “That sounds annoying.”

Shane Hanlon: 35:49 Yeah. Well, I mean, this is what we do on this platform is tell the world things we probably wouldn’t tell each other or people, because why not? Oh my. And with that, that’s all from Third Pod from the Sun.

Vicky Thompson: 36:04 Thanks so much, Devin, for bringing us this story and to Tommy for sharing his work with us.

Shane Hanlon: 36:08 This episode was produced by Devin with audio engineering from Colin Warren, artwork by Jay Steiner.

Vicky Thompson: 36:15 We’d love to hear your thoughts on the podcast. Please rate and review us, and you can find new episodes on your favorite podcasting app or at Thirdpodfromthesun.com.

Shane Hanlon: 36:24 Thanks all, and we’ll see you next week.

Vicky Thompson: 36:30 Why do you think they didn’t want me to drive the Zamboni?

Shane Hanlon: 36:33 Why do I think they didn’t want you to drive the Zamboni?

Vicky Thompson: 36:35 What about me says I can’t drive a Zamboni?

Shane Hanlon: 36:38 I mean, what were your skills? What were your qualifications?

Vicky Thompson: 36:42 I could drive a car.

Shane Hanlon: 36:43 Do you-

Vicky Thompson: 36:43 I can wave.

Shane Hanlon: 36:45 Did you ever drive a car that sits up 10 feet in the air that has rear steering and drags like-

Vicky Thompson: 36:52 Well-

Shane Hanlon: 36:53 … a thing that floats ice? I don’t know. I know that’s fair. But I feel like I drove a forklift before, which has similar … I also worked in a lumber yard. I forgot to mention that one. But I drove a forklift, which has rear steer, and I feel like that’s important from a Zamboni perspective because those things turn very differently than cars do.

Vicky Thompson: 37:12 Rear steer is different from rear-wheel drive. Rear-wheel drive.

Shane Hanlon: 37:17 Very different.

Vicky Thompson: 37:19 Oh. I was going to say, I’ve driven many, many old cars that have swooshed out on me, if that’s … But that’s different. Okay.

Shane Hanlon: 37:27 See that’s the thing. You put down, “classic car driver,” and they thought, “Nope.”

Vicky Thompson: 37:30 No, I didn’t put any of that down. I literally just walked in and was like, “Give me the application.” They were like, “Leave, please.”

Shane Hanlon: 37:34 I think that you have your answer.

Vicky Thompson: 37:36 I think they just looked at my face and said, “No, thank you.” That’s pretty good.

I enjoyed this podcast. Tommy sounds like a really interesting guy and teacher. Thanks for publishing this podcast!