Distillations: Mapping the seafloor with computer games

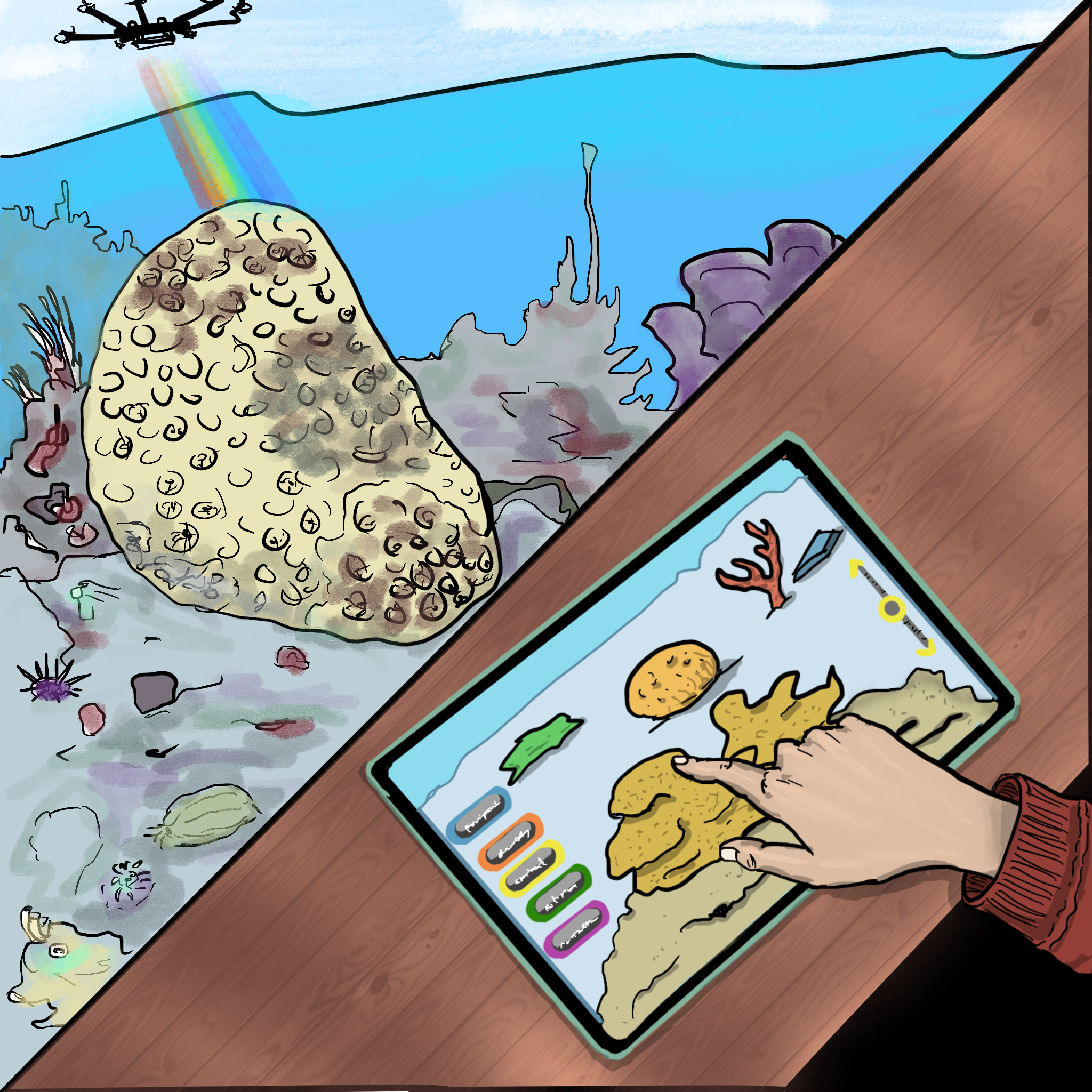

Many might think that we know most or all there is to know about our world. On the surface, that might be somewhat true. But below the surfaced, we’ve mapped less of the oceans than of places outside our world like Mars and our moon. Ved Chirayath is trying to change that, not by going down in submarines, but through…computer games. We chatted with him about how we can use the combined power of engaged non-scientists and games to learn about our own world.

Many might think that we know most or all there is to know about our world. On the surface, that might be somewhat true. But below the surfaced, we’ve mapped less of the oceans than of places outside our world like Mars and our moon. Ved Chirayath is trying to change that, not by going down in submarines, but through…computer games. We chatted with him about how we can use the combined power of engaged non-scientists and games to learn about our own world.

This episode was produced by Shane M Hanlon and mixed by Collin Warren. Artwork by Olivia Ambrogio. Interview conducted by Laura Krantz.

Transcript

Shane Hanlon: 00:00 Hi, Vicky.

Vicky Thompson: 00:01 Hi, Shane.

Shane Hanlon: 00:03 Have you ever created anything professionally or just for kicks for public consumption? And I had a hard time kind of explaining this, so something, think about it. Something for outreach or public outreach or something like that?

Vicky Thompson: 00:16 Yeah. Oh yeah, I have. I’ve done quite a few art fairs and I was in charge of the educational programming at the art fairs.

Shane Hanlon: 00:25 Oh.

Vicky Thompson: 00:25 So yeah. So I would work with artists and design. All sorts of stuff, from activities for kids up to just public engagement activities. We do yoga in the art galleries.

Shane Hanlon: 00:38 Okay. Cool.

Vicky Thompson: 00:39 Yeah. And we did some educational stuff for artists about their craft and businesses and stuff. So that was really, I love doing stuff like that actually. Yeah. So what about you?

Shane Hanlon: 00:47 Yeah. That’s super neat.

Vicky Thompson: 00:48 I assume you’ve done a lot of stuff.

Shane Hanlon: 00:50 Yeah. I mean, these days, I mean podcasts aside, obviously I’m more behind the scenes helping the folks that do the thing. But before AGU, I was a fellow with the National Academies and I worked in their museum that they had in the time in D.C. And I actually created this game that I called, I think it was Eco Blocks. This was a while ago, but the idea was to demonstrate environmental resilience. So basically if something happens in an environment, how long does it take to bounce back for different things like fire or hurricanes or different stuff? And it was basically, it was kind of roughly based on Jenga. So I remember there was a die and you’d rolled the die and each block had a different number associated with it. And each block was also associated with a different hazard. So if it was a hurricane, it was harder to move a block than say fire or something like that. I don’t know.

Vicky Thompson: 01:38 Oh.

Shane Hanlon: 01:38 But I’d love to go back. Actually, this reminded me, I’m going to go back and try to find it. But I have to say it was honestly one of the more creative things I’ve done professionally. And that’s saying something, considering we are here right now. It was an absolute blast.

Vicky Thompson: 01:55 That’s really, really cool. But I have to be honest that I heard you say Jenga, but it translated into my brain as Jumanji.

Shane Hanlon: 02:06 That’s the next one, Vicky.

Vicky Thompson: 02:07 Yeah.

Shane Hanlon: 02:07 I’m going to do one based on Jumanji.

Vicky Thompson: 02:13 Oh my gosh.

Shane Hanlon: 02:15 Science is fascinating. But don’t just take my word for it. Join us as we hear stories from scientist for everyone. I’m Shane Hanlon.

Vicky Thompson: 02:24 And I’m Vicky Thompson.

Shane Hanlon: 02:26 And this is Third Pod from the Sun.

02:31 All right. So it’s day five, the final day of our special series from our annual meeting. And the theme of today is open science.

Vicky Thompson: 02:43 Open science. Tell me more. What is open science?

Shane Hanlon: 02:48 That’s a great question. It’s a lot of things, but basically in the way I’m going to frame it, it’s the idea that information, data, et cetera, should be free, accessible, and available to all.

Vicky Thompson: 03:00 Yeah, that sounds pretty great.

Shane Hanlon: 03:02 Yeah, doesn’t it?

Vicky Thompson: 03:03 Yeah.

Shane Hanlon: 03:04 And our interview today comes from someone who’s using and making available open data to create some really amazing stuff.

Vicky Thompson: 03:11 Awesome. Let’s hear it.

Laura Krantz: 03:15 Ved Chirayath, thank you so much for joining us today.

Ved Chirayath: 03:18 My pleasure, Laura. Thank you for having me.

Laura Krantz: 03:19 So let’s talk about the game. What’s the objective? Because that’s always the first question you have to ask with a game.

Ved Chirayath: 03:26 Yes. So the objective with NeMO-Net is nothing short of mapping the entire ocean floor.

Laura Krantz: 03:31 Oh, that seems reasonable.

Ved Chirayath: 03:34 Drop in the bucket.

Laura Krantz: 03:35 Yeah. How long is that that going to take?

Ved Chirayath: 03:38 If we just used about a thousand PhD scientists, it would take a 3 million years by our estimates. So we’re trying to accelerate that a little bit with citizen scientists and lots and lots of super computing power.

Laura Krantz: 03:50 Nice. So how do you play?

Ved Chirayath: 03:52 So you play by starting off on a research vessel, digital research vessel that looks nicer than any actual research vessel I’ve been on in the open seas. And NASA invented an instrument called fluid cam and fluid lensing. And that instrument’s the first that has given us a view, a diver skill view of the underwater environment in 3D at the centimeter scale. So we were mapping all these areas with aircraft, with drones. Eventually we’re trying to get to satellite layers, and as of now we’ve mapped about 6% of the sea floor.

04:20 In the game, your job is to help us interpret all of that data. So we create a map of a coral reef, and it’s really complex even for experts to look at. If you go to the Amazon rainforest and you look at one square meter, there’s maybe 10 species that are there. In a coral reef, it’s easily 100 times that, in that same area. So for a super computer and artificial intelligence to classify that, it’s getting better and better at tasks. But there are certain ones that are just still very difficult. If you Google blueberry muffin and chihuahua or a sheep dog and a mop, you’ll find all these examples where AI is failing, it’s not giving a really good result. And that’s because it’s not really at the level of even a two to three year old.

05:03 So what we do in the game is have users give us all of that contextual knowledge, basically train our AI using their brains. There are 8 billion supercomputers walking around this planet, and each one of them can make a contribution. And that’s really what the game’s about. Is to get them in the game, looking at coral slowly but surely, learning different types of coral. And then helping train our supercomputer, how to classify it autonomously.

Laura Krantz: 05:27 Okay. So you’re looking at the coral. Are you also looking at the species that are there? Not just the coral species, but fish and all that too?

Ved Chirayath: 05:34 So right now we’re starting primarily with just shallow marine habitats. So in addition to coral, we’re looking at sea grass meadows, even bare sand and substratum, there’s lots of different categories. As NeMO-Net is expanding, people are getting more ambitious. They would like us to, with the newest version of an instrument, we can actually detect fish and large charismatic megafauna. So shark, sea turtle, things like that.

Laura Krantz: 05:55 Do we consider sharks charismatic?

Ved Chirayath: 05:56 I think they’re pretty charismatic and sweet. They have a lot of good, they have a lot of personality. I’ve spent a lot of time with sharks. I was terrified of sharks growing up. But one of the things that we hope the game accomplishes is that for a lot of folks that don’t have access to the water or physically not able to get to the water, it gives them that perspective. When you go to a national park and a rainforest, you’re immersed in that environment. You really connect with it and with water, I think one of the biggest challenges to conservation is just getting people there, getting them to see what it’s like.

06:26 There’s lots of gear. Diving is not for everybody. Sharks, things like that. It can be putting off. And the ocean is a dangerous place just like any forest is. But if you can get them to empathize, to see a coral reef, to start learning kind of its ins and outs and the creatures that live there, you create a kind of grassroots conservation effort. That’s what we had on land. And that’s why I think land resources are almost better protected than what we have in the ocean.

Laura Krantz: 06:52 I think a lot of people would be surprised to learn that we have actually mapped more of the moon and more of Mars than we have of our own planet because of the oceans. And because they have prior to fairly recently been considered fairly impenetrable for mapping purposes.

Ved Chirayath: 07:06 Impenetrable. And this endless resource, which now we’re beginning to understand is quite finite. Just to give listeners perspective, we’ve lost entire jet planes in the ocean that have not been recovered for 10 plus years. On Mars, we lost a rover the size of a golf cart, and within one week we had a satellite image of the crash site. We had a satellite image of the parachute. That’s the level of technical mismatch there is between what we can do in the outermost planets and our own home world.

Laura Krantz: 07:34 So mapping the ocean, this is a big challenge. I mean, what’s the scale of the game? Because it seems that doing it centimeter by centimeter is going to take, it’s going to take a while.

Ved Chirayath: 07:46 It will. And there’s different ways of mapping the ocean. There are very good acoustic maps already of the ocean. This is what ships used to navigate. So they make sure they don’t hit a [inaudible 00:07:57]

Laura Krantz: 07:55 Sonar, and yeah.

Ved Chirayath: 07:57 Sonar and you can find vessels. The Titanic was found first through a sonar survey by one of my colleagues, Bob Ballard. But those technologies, they give you a very coarse view. It’s like looking at trees and just looking at their shape. Very chunky shapes.

Laura Krantz: 08:11 If you haven’t put your glasses on in the morning when you get out, as someone who’s nearsighted, I get out of bed and I’m like, that’s the door over there. I can tell you what the color is. I can’t tell you the outline or anything like that.

Ved Chirayath: 08:21 General shapes. Really general shapes. And so as a result, our knowledge of those ecosystems is equally impaired. We with acoustic systems, have mapped quite a bit of the ocean floor. We still lose entire jet planes. So it’s not like we have even really fully mapped it with sonar. But the way that we on land have done it for more than 60 years at this point is multispectral remote sensing. So this is using light. It’s particularly the visible wavelengths of light to study the different properties of an object. And with multispectral remote sensing, we can look at one of these things. And I can tell you for example, this is synthetic and not in fact real because it’s multispectral reflectance is different. Whereas if you look at that with a sonar, it actually looks exactly like a real plant, right? There’s no acoustic difference. So that’s why we are spending so much time looking at mapping the sea floor the same way we do land.

Laura Krantz: 09:11 People are asking, what is the importance of mapping the entire sea floor? What is, aside from these species, why is it important for us to have done the kind of mapping work with Earth that we have done on Mars and the moon? What’s the value in that?

Ved Chirayath: 09:26 Yeah, I mean, it’s nothing short of our survival. One of the predictions I made, and we got a lot of flack for it at the time, was when we released NeMO-Net. And people said, well, this is in the middle of the coronavirus pandemic. Why should we care about preserving coral reefs in the middle of this? And I said, listen, I guarantee you, the next drug to treat Covid is likely going to come out of one of these reef systems. And sure enough, six months later, a drug 30 times more effective than Remdesivir came out of a sea squirt in one of the reefs that we mapped. And that’s an environment that that species may have gone extinct in the next couple years if we had not provided habitat maps to say, “Look, there is biodiversity here.”

10:02 And with that comes with corals in particular. They have the, there’s sort of the 21st century medicine cabinet. They have all of these advanced compounds to fight disease, to fight viral compounds.

Laura Krantz: 10:13 Parasites.

Ved Chirayath: 10:14 Parasites, because they don’t really move that fast. They actually do move on sort time skills. But it’s all chemical and biological warfare. And so if you’re looking for drugs just for the first thing, this is where it’s at. This is where you’re going to find most of the medicines to treat ailments that affect humans. It’s not just Covid that was treated with reef systems. The leading blood pressure medications came out of corals, cancer compounds, the list goes on. And that’s just corals, corals support, on top of that, all of these other organisms in the ocean, which also provide these compound. Sharks have amazing abilities to fight cancer among other diseases.

10:50 And so that’s one component of, why should you care? Well, if there’s another pandemic, which I’m nearly certain there will be, we’re going to rely on this medicine cabinet to treat us ourselves. And if we on our watch, let that biodiversity putter out, that’s evolved for billions of years. We lose with it the potential to treat ailments that will affect our species. Of all the species on the planet, humans are some of the least diverse, despite however much differences we try to create amongst ourselves. We’re genetically almost identical. It’s scary. And so as a result, when a pathogen does emerge, it tends to wipe out large swaths of population very quickly.

Laura Krantz: 11:28 And is this information that is coming out of the game available to all the scientists and other people who might be interested in getting access to it?

Ved Chirayath: 11:37 We’ve got 85 year old playing it who’s super into it. And she can out perform me regularly. So I’ve sort of given up, I’m the lower tier level as you ranked up in the video game. There’s the whale shark is the top level, so there’s a couple of our whale sharks. And then you start off as a plankton. Very small.

Laura Krantz: 11:55 I love it. If somebody wanted to get involved with this, how would they go about doing it? How would they become a plankton first and then hopefully a whale shark?

Ved Chirayath: 12:03 Yeah, I mean, just go to nemonet.info or just type in NASA NeMO-Net and download it. It’s available for Windows, Androids and iOS devices. We tried to make it as universal as possible. We’re working with some bigger agencies to make it a more professional tool for them to use to classify. But all the data will remain open source. And then you start up the game, you get a profile. I think mine’s Sir Captain Narwhal or something. You can get some auto-generated ones, and then you can compete with different friends and family members. So that’s some of our best outcomes are when people get competitive.

Vicky Thompson: 12:37 How do you think your plot game stacks up to what Ved is creating?

Shane Hanlon: 12:50 Okay, so I’m proud of what I’ve done, but it doesn’t, and that’s fine. I’m so happy that there are folks out there like that doing the work that they’re doing. And so with that, that’s the last of our episodes in a special series. And that is all from Third Pod from the Sun.

Vicky Thompson: 13:08 Special thanks to Laura Krantz for conducting the interview and to you, Shane, for producing this episode and our episodes this week. Audio engineering was by Collin Warren with Artwork by Olivia Ambrosio.

Shane Hanlon: 13:20 If you’d like to see a video for at least part of this interview, you can head over to YouTube and search for AGU TV.

Vicky Thompson: 13:28 We’d love to hear your thoughts. Please rate and review the podcast and you can find new episodes in your favorite podcasting app or at thirdpodfromthesun.com.

Shane Hanlon: 13:36 Thanks all, and we’ll see you next week.