31-Spaceship Earth: Using satellites to feed the world

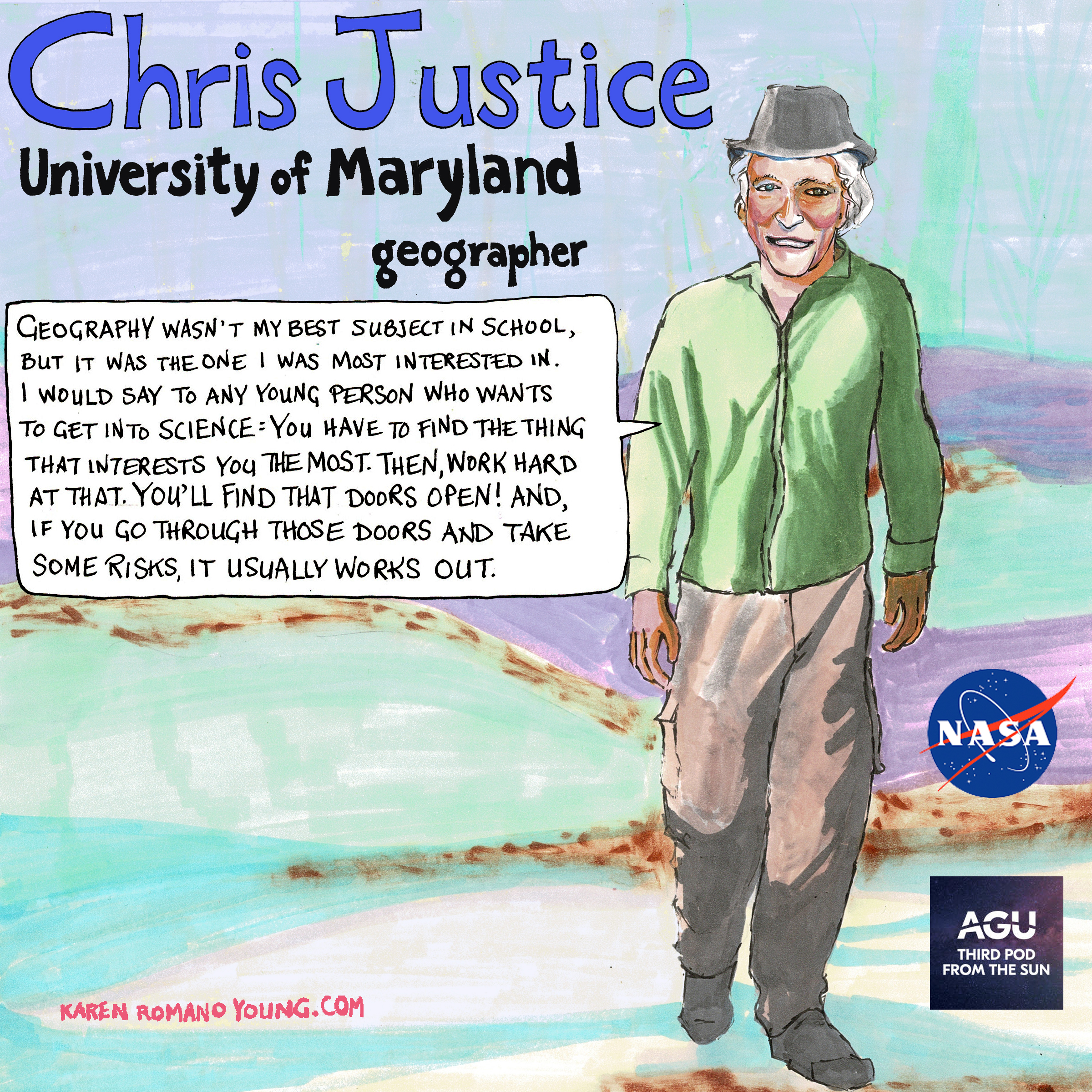

Chris Justice is a geographer and professor at the University of Maryland whose research on land use changes and global agriculture has taken him around the world. His research has had a hand in a variety of NASA programs, including the Moderate Imaging Spectroradiometer (MODIS), Mission to Planet Earth, and the creation of the Global Inventory Modeling and Monitoring group. He talks to us about his journey into science, NASA’s relationship with agricultural research, and how NASA’s using satellite data in its Harvest Mission to tackle global food security.

Chris Justice is a geographer and professor at the University of Maryland whose research on land use changes and global agriculture has taken him around the world. His research has had a hand in a variety of NASA programs, including the Moderate Imaging Spectroradiometer (MODIS), Mission to Planet Earth, and the creation of the Global Inventory Modeling and Monitoring group. He talks to us about his journey into science, NASA’s relationship with agricultural research, and how NASA’s using satellite data in its Harvest Mission to tackle global food security.

This episode was produced by Jason Rodriguez and Shane M Hanlon, and mixed by Collin Warren. Artwork by Karen Romano Young. Interview conducted by Ashely Hamer.

Transcript

Shane Hanlon: 00:00 Hi Vicky.

Vicky Thompson: 00:00 Hi Shane.

Shane Hanlon: 00:02 All these questions are usually kind of silly, but I’ve got a little bit of a weird one for you. What are some fond, or not so fond, memories or experience have you had on farms or related to farming?

Vicky Thompson: 00:17 Well, I didn’t have a ton of farm experience in my life so far. In the fall, we went to … I did my first, maybe second corn maze.

Shane Hanlon: 00:29 Oh, sure.

Vicky Thompson: 00:29 Yeah. I did it with my husband and my daughter, and it was after a long day. We had done a hay ride, and we pet all the animals, and we did all of the things, so I was already really tired and wind blown and sun chapped, or all of the things that you could be. So we’re running around in this corn maze, which did not seem very challenging when we rolled up because the corn was … I could see over the top of the corn, so I was like, “What kind of corn maze is this even?” But then I’m tired, and we get into it with a very stubborn and opinionated five year old, who knows the way.

Shane Hanlon: 01:05 Of course.

Vicky Thompson: 01:06 But also, you can’t see her over the top of the corn, so I thought we were never going to get out of just trudging along. It was not good, but we got out, here we are, so that’s good.

Shane Hanlon: 01:20 I feel like that’s a way that a lot of folks at our point in life and in the region especially in which we live experience farms these days. It’s corn mazes, pumpkin patches, for better or for worse.

Vicky Thompson: 01:32 Yeah. Just like being too tired and just terror, I don’t know, it just feels like a lot. [inaudible 00:01:40].

Shane Hanlon: 01:42 Thinking it was a good idea at the time, and then it’s just like, “Why did we actually decide to do this?”

Vicky Thompson: 01:45 It’s like Olivia lives in the corn now, I’m not sure. Yeah, so that’s me.

Shane Hanlon: 01:51 Oh, my gosh. Well, so I grew up in very rural Pennsylvania.

Vicky Thompson: 01:56 Rural Penn.

Shane Hanlon: 01:57 Yeah, I said it before you do. You could see you winding up to it.

Vicky Thompson: 01:58 Darn it. You saw me winding up. Okay.

Shane Hanlon: 01:59 Yeah.

Vicky Thompson: 01:59 I’ll get you next time.

Shane Hanlon: 02:05 And weirdly, mine has a little bit of a Children of the Corn relation as well. Yours was a child of the corn. But I used to go to this summer camp in the area where I’m from, and it was very kind of low key, low stakes, very informal type deal. But there was, I don’t know, from adolescents to 17, 18 year olds or something like that. And we would do kind of adventure activities and all sorts of stuff, and there was leadership things and all that jazz. But one of the things that the older kids always liked to do to the younger kids was just scare the absolute crap out of them on day one or two of the camp. And so basically, we’d go on a … The younger kids would go on a nighttime walk through the corn fields.

Vicky Thompson: 02:59 What?

Shane Hanlon: 03:00 And the older kids would essentially do a reenactment of Children of the Corn.

Vicky Thompson: 03:05 Why?

Shane Hanlon: 03:08 [inaudible 00:03:07]. Because it was kids and boys. I don’t know, it was just-

Vicky Thompson: 03:13 Just terrible.

Shane Hanlon: 03:14 There was nothing … It was harmless fun. But they would just yell at you. It was essentially like a haunted hayride almost, except probably more terrifying. But yeah, that’s some of the memories I have.

Vicky Thompson: 03:36 I have so many questions. Wait. So did the adults in the situation know this was going to happen? I guess they anticipated it. Right?

Shane Hanlon: 03:40 Unclear. Probably, but I don’t know. These are memories that come in spurts, where I go, “Oh, that was weird. Okay.”

Vicky Thompson: 03:52 Oh, that’s what happened to me.

Shane Hanlon: 03:53 That’s what happened. That’s why I am the way I am. Science is fascinating, but don’t just take my word for it. Join us as we hear stories from scientists for everyone. I’m Shane Hanlon.

Vicky Thompson: 04:11 And I’m Vicky Thompson.

Shane Hanlon: 04:12 And this is Third Pod from the Sun. So Vicky, we’re talking farms and crops today, not only to share our sometimes personal ill fated corn and farm experiences, but to hear some amazing work that folks are doing around food security.

Vicky Thompson: 04:37 So food security, I feel like we would’ve been in our stories, pretty secure in our corn fields if need be. Right? If I were to have never made it out of the corn field, just eat my way through.

Shane Hanlon: 04:49 Yeah. I don’t know if I’d love eating raw corn.

Vicky Thompson: 04:54 Oh, yeah.

Shane Hanlon: 04:56 Do you know the corn kid on TikTok? It’s corn.

Vicky Thompson: 04:59 Oh, yeah.

Shane Hanlon: 05:00 He might be cool with it. I’ve never really loved corn. We are getting off topic.

Vicky Thompson: 05:04 Way off track.

Shane Hanlon: 05:05 Yeah. So what we’re actually talking about today is we’re going to hear from a NASA scientist who uses satellites to solve problems, including food security, all around the world. Our interviewer was Ashley Hamer.

Chris Justice: 05:19 So my name is Chris Justice. I’m a professor in the Department of Geographical Sciences, University of Maryland.

Ashley Hamer: 05:35 Nice. And what does that entail?

Chris Justice: 05:40 So I do research on various aspects of land use change using satellite Earth observations with a current emphasis on global agriculture, food security, but previously on other topics including fire. My research over the years has been supported by NASA, and I contribute to NASA’s Earth science program as a university professor training the next generation of scientists at the graduate and undergraduate level. That’s also a major part of what I do. I’ve always been involved in international science programs working with international colleagues on common global problems. What does it involve? Communicating with people, doing my own research, writing paper, analysis, getting results out, and sharing them with the broader community.

06:35 I spend quite a bit of time translating science results into digestible material for public and for policy making community. At the moment, we’re involved in an applied sciences program with NASA on agriculture, it’s NASA’s agricultural program called Harvest. This is taking NASA satellite data and the science is being developed around that, and making it useful for societal benefit. The website is nasaharvest.org, and that’s a good place to go look and see what we’re doing. There’s lots of information. Working on food security in Africa, working on, as I said, the crop production in Ukraine, working on new methods for extracting information from satellites on crop production and yield, and looking at the major producing countries around the world, the grain producers for the commodity crops, and looking at shortages and if there’s drought, and if there are problems in agricultural production, and then what the impacts are on the global market and the impacts on supply chains that we’ve been experiencing.

Ashley Hamer: 07:48 I think that might surprise some people that NASA is interested in agriculture. Could you talk more about that, why NASA’s involved with that?

Chris Justice: 07:56 Well, there’s a long history of NASA involved in agriculture. The first satellite that was put up was the Landsat program. Landsat was launched 1972. And one of the rationales and justifications for that was looking at agriculture, so there’s been a program of agricultural remote sensing for a long time run by NASA. But recently, it’s increased and they’ve developed a new program aimed at looking at global food security, and just recently, domestic agriculture. It’s really the only way of figuring out what’s going on and trying to give some early advance notice of drought and sort of food security issues in parts of the world perhaps don’t have the same monitoring systems that we do here in the US.

Ashley Hamer: 08:45 Nice. Yeah, that’s really important. So backing up, what is it that drew you to science originally?

Chris Justice: 09:01 I was a geography major in the UK, and I got my PhD using Landsat data at about the time that it started to become available, just as digital data was starting to become available. Initially, Landsat was photographic products that were distributed. I had training in air photo interpretation through the university that I was working there. They had a project using a British rocket that took photographs as it descended. We worked in Argentina and Australia, and I applied to be a research assistant, got really excited about it, enjoyed it. And then I was fortunate enough to meet a colleague of mine now, who was visiting the UK from NASA Goddard Space Flight Center, name was Jim Tucker. And he encouraged me to apply for a national research council postdoc, which I did. And I went out to Goddard Space Flight Center at a time when satellite data was really starting to get used, and so that was the beginning.

10:05 When I finished my time at Goddard when my visa expired, I went back to Europe. I worked for European Space Agency in Frascati. And they were developing a capability to distribute Landsat data themselves. And I worked there for three years and then came back to Goddard in 1983 to work on the NOAA advanced very high resolution radiometer, which was an operational weather satellite, but we started to use it for Earth observation, looking at the land surface. And Jim Tucker started to work on this operational course resolution satellite, but the unique thing about that was that it had daily observations at the global scale.

10:53 And so we put together a group of researchers, Jim Tucker, Brent Holben, Yoram Kaufman, Eric Vermote. And we started to use these daily global observations for looking at the surface, and we called the group the Global Inventory Modeling and Monitoring Studies Group, Jim’s group, Jim Tucker was the originator and we grew this into a core of researchers from around the world and started what has now become known as time series land remote sensing. And it was grounded in the use of an index, which Jim Tucker had developed, called the normalized difference vegetation index, which allowed you to look at vegetation condition around the world. And so this was the start of this global Earth observation program that I’ve been working on since that time.

Ashley Hamer: 11:42 Wow, so this group really pioneered the thing that you’re currently working on.

Chris Justice: 11:48 Yeah, it was really an exciting time, and a lot of people were involved in that, and certainly not just me. And it’s grown into a much bigger program. So when NASA embarked on Mission to Planet Earth, which was a program to start getting coordinated observations for the Earth surface, which became the Earth Observing System, EOS, I was invited to join an instrument team to develop something better and more scientific than the operational weather satellite system that we were using, led by Vince Salomonson, who was the division head at Goddard at that time. I was involved in putting together the requirements for the land community, and then negotiating with the other disciplines on which of those got accepted onto the mission.

12:38 So having had the experience with Landsat and this weather satellite, my vision was to put together a global coverage on a daily basis with the scientific capability that Landsat offered, and then add some additional spectral bands for measuring fire and thermal land surface temperature, and that was the beginning of what we call now the moderate resolution imaging Spectroradiometer, the MODIS instrument, which was put up in space. I think one of my biggest achievements was to put on that instrument two spectral bands with a spatial resolution, that’s sort of the size of the smallest thing you can see at 250 meters, which at that time really pushed the envelope. There was a lot of resistance to that in terms of data volume, global data, every day for 250 meters. Of course, that was at a time when computers were a lot more challenged by volumes of data than they are now.

13:46 The capability now for monitoring the Earth’s surface is pretty much built on that, and that was the launch of these two MODIS instruments, Terra and Aqua, morning and afternoon overpasses, 1999 to 2002. So those instruments were planned for five year life, but remarkably, 20 years later, they’re still operating, which is a testament to the quality of the engineering. And of course, with that length of time period, we’ve been able to look at changes on the land surface, and it’s been a major success for the NASA program. For working with two people, Louis Giglio, Yoram Kaufman, who’s also no longer with us, we created what’s called the MODIS Active Fire Product, which detects fires as they’re burning, and is still used today by agencies around the world to look at the location of fires, including the US Forest Service.

14:46 We got a call from the US Fire Service to say, “We hear we’ve got a new instrument that can measure fire. Can we get the data?” And I said, “Well, the trouble is we can’t process it very quickly, so you can have it in three months.” And they said, “Well, that’s no use to anybody. We want to know where the fires are today, right now, so we can actually do something about it.” And so we made the case for a rapid response system that would give the satellite data, process it within two hours, and that’s turned into a capability which still exists called the Land Atmosphere Near Real-Time Capability for EOS, LANCE. And so that was another large success I think of the NASA program.

Ashley Hamer: 15:28 Wow.

Chris Justice: 15:29 Yeah, there you go.

Ashley Hamer: 15:30 Yeah, that is a huge, very impressive career. My goodness. But before that, first, I don’t know if you mentioned. What was your PhD in?

Chris Justice: 15:41 Geography.

Ashley Hamer: 15:42 Oh, wow. Okay.

Chris Justice: 15:44 I’ve always been interested in geography. It wasn’t my best subject, but it was the one I was most interested in. And I would say for any sort of young person that wants to get into science, you really have to find the thing that interests you the most, and then work hard at that, and you’ll find that sort of doors open.

Ashley Hamer: 16:08 Yeah. Who would’ve known that an interest in geography could lead you to doing all of this? That’s amazing. What about the thing that you’re most proud of?

Chris Justice: 16:25 I think as I just said, I think putting those spectral bands, those 250 meter bands on the MODIS instrument was a real game changer for the community, and really made a huge difference. I’m proud of that.

Ashley Hamer: 16:40 And actually, so 250 meters. That’s about two and a half Olympic swimming pools. What is that compared to?

Chris Justice: 16:48 You do 100 meter length.

Ashley Hamer: 16:50 Sure, sure.

Chris Justice: 16:52 It’s still pretty coarse, but if you’re looking at the world every day and collecting all of that data, it’s still a lot. But of course, the technology’s changed completely, so now people are using data from once they got the acquisition collecting the data, enough data, and dealing with the data, processing data management people are now using 30 meter data and 20 meter data to do the same global work, but it’s the same principles and the same processes, but just going finer and finer. Of course now with commercial satellites, you can get data at half a meter and make it available. But again, that’s commercial, so it’s not widely accessible. NASA has a program for purchasing some of that high resolution data. But part of the team that I work on now is using those data from Planet, which is one of the commercial data providers to look at and do an assessment in real-time of the agricultural conditions in Ukraine, and that’s proven to be extremely helpful for the Ukrainian government.

Ashley Hamer: 17:59 That’s important, yeah.

Chris Justice: 18:00 Working with the Ministry of Agriculture. Because you need fine resolution data for looking at the detail. The coarser resolution data looks at changes in condition. But if you’re trying to map the individual fields and do the acreage estimates for crops, you need finer resolution data. So looking down at three meters and less, and combing that with 10 meter data from the Europeans, and 20 meter data from Landsat, then you’ve got that global monitoring system where you have daily coverage, and then every two or three days, you get full resolution coverage.

Ashley Hamer: 18:36 That’s good. That’s good. What is your favorite place to do science?

Chris Justice: 18:41 In the field, definitely, when I do the data collection. It’s hard work, but you really get to understand what’s going on.

Ashley Hamer: 18:50 Yeah, you’ve got to make that comparison between the satellite data and the boots on the ground, like you said.

Chris Justice: 18:54 Boots on the ground, yeah. And then you can do that both for the validation, accuracy assessment of the satellite data, but also then to train the sort of machine learning approaches to classify the data or to identify the features that you’re really looking for.

Ashley Hamer: 19:11 Oh, right. Yeah. So you use a lot of machine learning in this too.

Chris Justice: 19:15 Yes, and have for many, many years.

Ashley Hamer: 19:18 You were mentioning how hard it was back in the day to collect that much with the 250 meters.

Chris Justice: 19:25 Yes.

Ashley Hamer: 19:26 Yeah, to collect that much data. And now we have so much more, but you just need to wade through it and find a way to do that.

Chris Justice: 19:32 Exactly. And the cloud computing’s really helped, so it means that you have access to large volumes of data and sort of high capability computing, whereas back in the day, there just wasn’t that capability at all. And now it’s all digital, and what used to be a huge warehouse full of computers is now pretty much underneath your desk or on your laptop.

Ashley Hamer: 20:02 Things really change.

Chris Justice: 20:03 You have change. And it just shows you how old I am.

Ashley Hamer: 20:07 Well, you made a lot of that happen it sounds like too.

Chris Justice: 20:10 Some. But as I said, it’s not on me. It was a group effort and a lot of people involved, and a lot of people deserve the credit. I just happened to be in the right place at the right time.

Ashley Hamer: 20:21 Yeah, that’s great. So outside of your job, if you could be doing anything outside of the sciences, what would that be?

Chris Justice: 20:30 I would probably work for a non government organization, looking at ways to help people live more sustainably in terms, without degrading the environment. And that’s something that I believe in that we need to try to get that sort of working now, whether it’s because of climate change or because of there’s now eight billion people on the planet as of this week, so I understand.

Ashley Hamer: 20:55 Oh, really?

Chris Justice: 20:55 Yeah.

Ashley Hamer: 20:56 This week.

Chris Justice: 20:56 So we’ve got a lot of people that need feeding, and we’ve got a lot of land that then will be used for that. So how do we sustain your human life without degrading the environment? And it’s something that we’ve been talking about for many years, but we’re not doing very much, so I think the non government organizations probably are the most effective at sort of making that happen, at least lobbying for that to happen.

Ashley Hamer: 21:20 That’s very related to land monitoring. Well, great, thank you so much for talking with me. You have had an amazing career, and I think people will be really interested in hearing about it.

Chris Justice: 21:30 I feel very fortunate, actually, very lucky.

Ashley Hamer: 21:33 Wonderful.

Chris Justice: 21:34 And I think that’s something that I can be grateful for.

Vicky Thompson: 21:46 So really, I think that finding ways to keep everyone on Earth fed is so important. It’s just going to get more and more important as we move forward.

Shane Hanlon: 21:55 Yeah. I agree. And thinking about food and farming and crops in this way is probably a much better use of time than some, I don’t know, in my case some backwoods Children of the Corn reenactment. And I want to thank Chris for sharing his work with us. All right, folks, well, that’s all from Third Pod from the Sun.

Vicky Thompson: 22:22 Special thanks to Ashley Hamer for conducting the interview and to NASA for sponsoring this series.

Shane Hanlon: 22:27 This episode was produced by Jason Rodriguez and me, with audio engineering from Collin Warren, artwork by Karen Romano Young.

Vicky Thompson: 22:36 We’d love to hear your thoughts. Please rate and review us. And you can find new episodes in your favorite podcasting app or at thirdpodfromthesun.com.

Shane Hanlon: 22:44 Thanks, all. And we’ll see you next week.

Vicky Thompson: 22:53 So I feel like since you put the Santa hat on Tacoma, then you’re going to have to always … I feel like you should just have a rotating hat.

Shane Hanlon: 23:00 I can do that. Yeah, I have a lot of hats. I’m a hat person. So for the new year, I’ll put my HU tassel cap that I got on him.

Vicky Thompson: 23:10 Nice.

Shane Hanlon: 23:11 We’ll keep that on him for the winter. And then yeah, I’ll give him some trucker hats and all sorts of different stuff.

Vicky Thompson: 23:19 Did you call it a tassel hat?

Shane Hanlon: 23:21 Tassel cap.

Vicky Thompson: 23:22 Tassel, tassel?

Shane Hanlon: 23:25 It is tassel, isn’t it? Yeah, it is tassel.

Vicky Thompson: 23:25 I would call it a pom pom hat.

Shane Hanlon: 23:26 I call it … It should be tassel, I say tassel. But yeah, I say tassel.

Vicky Thompson: 23:37 I was just making sure I was talking about the same thing.

Shane Hanlon: 23:40 I think it’s a … Yeah, I wonder if that’s the regional … Yeah. There must be a regional thing about it because, yeah, I’ve heard pom pom too.

Vicky Thompson: 23:52 Knit cap.

Shane Hanlon: 23:52 I don’t know why I call it tassel.

Vicky Thompson: 23:55 That’s good.