34-Spaceship Earth: Powering humans in space

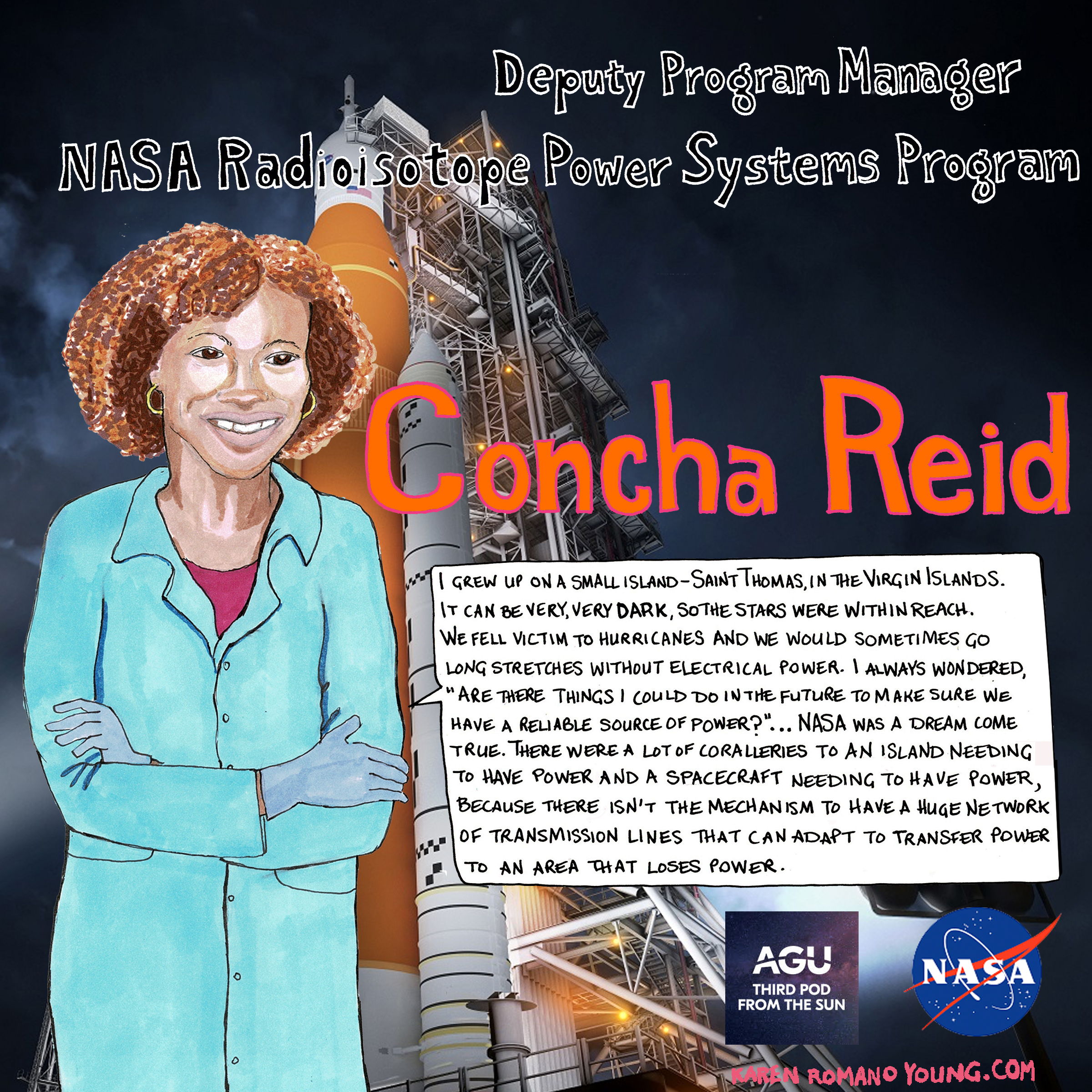

As the Deputy Program Manager for NASA’s Radioisotope Power Systems Program at Glenn Research Center, Concha Reid leads a team overseeing and monitoring devices that heat and give power to NASA space projects, such as the recent Orion spacecraft for Artemis 1. She sits down with us to talk about growing up in the Virgin Islands and how that inspired her to study Electrical Engineering, her non-traditional path of taking time off to raise a family and finding her way back into the science community, and her excitement for the future of NASA’s space missions.

As the Deputy Program Manager for NASA’s Radioisotope Power Systems Program at Glenn Research Center, Concha Reid leads a team overseeing and monitoring devices that heat and give power to NASA space projects, such as the recent Orion spacecraft for Artemis 1. She sits down with us to talk about growing up in the Virgin Islands and how that inspired her to study Electrical Engineering, her non-traditional path of taking time off to raise a family and finding her way back into the science community, and her excitement for the future of NASA’s space missions.

This episode was produced by Jason Rodriguez and Shane M Hanlon, and mixed by Collin Warren. Artwork by Karen Romano Young. Interview conducted by Ashely Hamer.

Transcript

Shane M Hanlon: 00:00 Hi, Vicky.

Vicky Thompson: 00:01 Hi, Shane.

Shane M Hanlon: 00:03 Are you a naturally warm or cold person? I mean temperature-wise, not in affect, but yeah. Are you naturally run warm, do you run cold?

Vicky Thompson: 00:15 Oh, I run so, so hot all the time. I’m just so hot, constantly. I always think of this cartoon I saw on the internet somewhere, where it’s just like somebody, a little figure, and it’s like, “I’m too hot. My skin, my skin, I’m too hot. Get it off me.” That’s me.

Shane M Hanlon: 00:34 Do you keep your house warm then in the winter? Is your family like this as well?

Vicky Thompson: 00:41 No. So I feel like Olivia, we haven’t figured that out yet. She’s just kind of all over the place. My husband, so Brian is, does not run hot, and he’s also not inclined to put on a pair of socks if he’s cold. So I feel like we keep our thermostat up too. I’m just always in the middle of the night. I’m always throwing off the blankets. It’s just, “Ugh. Terrible. Oh my gosh.”

Shane M Hanlon: 01:09 I understand that.

Vicky Thompson: 01:11 You do?

Shane M Hanlon: 01:12 Yes. I am a furnace. It’s just not great ever, frankly. It’s not good in the summer and in the winter, we keep our place pretty cool. The way our heating works is that we can heat individual rooms, which works out really well for us, because my wife is similar to your husband. She’s not warm, never warm. We’ll put on more clothes though, because that’s the one thing I’ve always said, maybe it’s a cop out, but when you’re too hot, you can always put more clothes on. Or excuse me, you’re too cold, you can always put more clothes on, but you can only take so many clothes off.

01:50 But yeah, I 100% am with you on we turn our thermostat down really low at night and still, I’ll wake up in the middle of the night. I used to think I was sick, like there was something wrong with me. I’ll just wake up in the middle of the night in December when it’s 30 degrees out and I’m just not necessarily pouring sweat, but just so warm and uncomfortable and whatever. And yeah, my wife is the exact opposite and I get the cold hands and the cold feet and…

Vicky Thompson: 02:16 Yes, oh my God. Don’t touch me with your feet.

Shane M Hanlon: 02:20 Yeah, yeah. Don’t totally.

Vicky Thompson: 02:22 Oh, with your cold feet, specifically.

Shane M Hanlon: 02:30 Science is fascinating, but don’t just take my word for it. Join us as we hear stories from scientist or everyone. I’m Shane Hanlon.

Vicky Thompson: 02:40 And I’m Vicky Thompson

Shane M Hanlon: 02:41 And as his Third Pod from the Sun. So we’re talking about heating and being warm and cold because our guest today works with batteries, stick with me. Specifically, nuclear batteries, which just those two words together to me are absolutely wild. But because they’re used in, or at least in part, to provide heating in some really inhospitable environments.

Vicky Thompson: 03:10 Inhospitable environments?

Shane M Hanlon: 03:12 Like space.

Vicky Thompson: 03:14 Like space. Oh, okay.

Shane M Hanlon: 03:16 I don’t want to [inaudible 00:03:16] too much, but very cold environments.

Vicky Thompson: 03:19 Yeah, so cold. But batteries and inhospitable environments make me think of, we just came off a fall meeting, so convention centers are so cold.

Shane M Hanlon: 03:30 They are pretty cold.

Vicky Thompson: 03:31 They are inhospitable. So batteries, our lovely coworker, Matt, had a battery powered jacket, warming jacket at the fall meeting that I don’t know if it worked too well, but it was, I don’t know that it actually kept its battery very long. It kept its charge.

Shane M Hanlon: 03:57 Yeah, I’m familiar with the jackets, I actually, back to my wife, because she’s always cold, I’ve got her socks and gloves that are battery powered so we can go hiking, or go skiing, or anything like that. And I feel like those hold a little bit better, just because they’re a little bit smaller. But yeah, lots of examples of batteries heating things.

Vicky Thompson: 04:23 Bodies.

Shane M Hanlon: 04:24 Bodies. And in the case of our interview today, not just people and frankly not just batteries. And so without meandering too long, or too much longer, let’s just get into it. Our interviewer was Ashley Hamer.

Concha Reid: 04:47 My name is Concha Reid. I work for the National Aeronautics and Space Administration at Glenn Research Center in Cleveland. I am the deputy program manager for NASA’s Radioisotope Power Systems program, and this is under the NASA headquarters Science Mission directorate and the Planetary Sciences Division.

05:07 So in short, I do manage the development of these systems that we call radioisotope power systems. And these are for use on NASA missions, primarily science missions, but not necessarily restricted to science missions. So we call these RPS for short, because it’s kind of a mouthful, and these can be likened to a nuclear battery. These systems, they harvest the heat from the natural decay of plutonium 238, and we use this heat to provide warmth for systems in cold environments. As you can imagine, the vacuum of space is pretty cold, as well as some of the planetary surfaces that NASA targets for its missions can be very cold as well, depending on where.

05:58 And so then that heat is then either used just to provide that warmth, or it can be converted to electrical power. And then along with other devices, we use this electrical power to provide a very long-lived source of power for use in dark, colder reaches of the so solar system. So you may be familiar with some of the missions that these systems have flown on. For instance, the Voyager missions are in their 45th year, and these radioisotope power systems have powered two Voyager spacecrafts on their mission for all of this time. In additionally, the rovers that are on Mars, they have all utilized radioisotope power systems to either generate heat or power.

Ashley Hamer: 06:44 Wow. Okay. So is this, when someone says that a spacecraft has nuclear power, is this what they’re talking about?

Concha Reid: 06:52 It could be. There are different types of nuclear power sources. The radioisotope power that we use is strictly utilizing the decay of the radioisotopes. There are other types of nuclear power. For instance, the power plants that are used here on earth use a different type of nuclear power.

Ashley Hamer: 07:17 Got it. Okay. So a bunch of different kinds, but this is one. Nice. And so what do you do specifically with this radioisotope power? What do you in your role?

Concha Reid: 07:28 Oh, yeah. So we do things like look across the spectrum of things that NASA needs. These would be design for missions, or let’s say, the needs that the science community would like us to observe in space. We keep our eyes out for that. We look out for the types of missions that NASA is planning, and then we try to determine how our power systems can help to fulfill those needs. We then develop the power systems. We look at the requirements, meaning how much power will be needed and how much life will be needed, what is the environment that these power systems will need to operate within.

08:17 Then, once the mission is launched, we do monitor what we call telemetry, which is the data that comes back to earth from the spacecraft so that we can ensure that the power system is in good health. And along with it, there’s a lot of other, let’s say, institutional and administrative types of things that we need to do. We have to manage the risk, for instance, we have to look at the budgets, ensure that we’re meeting schedule. And so myself and my fellow managers look out and ensure that all of those things are, that go into the whole spectrum of ensuring a successful mission take place.

Ashley Hamer: 09:00 Great. Yeah, that’s a big job. That’s a lot to do.

09:09 So to zoom out, what drew you to science in the first place?

Concha Reid: 09:14 So that goes back to the beginnings of me. I grew up in a really small island, the Saint Thomas and the Virgin Islands. And there’s not a lot of, let’s say, light pollution there, because it’s a very small place and at night it can be very, very dark. And so the stars were within reach when I was growing up. So growing up, because again, being a small island, we didn’t have the benefit of a lot of backup power like places in the United States have, for instance. And we fell victim to hurricanes a few times during my young life. And so we sometimes would go long stretches without having electrical power. And I just always wondered, well, are there things that I could do in the future to try to make sure that we have a more reliable source of power? And this also drew me, when I was in my high school years, for instance, I was very interested in math and science, and I had really wonderful chemistry teacher who also happened to be my physics teacher and just had a natural love for teaching and for educating young folks.

10:38 And all of these things helped to inspire me to study electrical engineering and science in college. And then once I got into my career path, there are times where as an engineer, I was more a scientist than an engineer, if that makes sense. The types of things that I was doing to develop power systems, for instance, I started off at NASA working in the electrochemistry branch, which is studying the chemical conversion of energy and things like batteries and fuel cells. So it all at some point got interwoven. So I consider myself a scientist as well as an engineer, even though my formal training and degrees are in the engineering field.

Ashley Hamer: 11:27 That’s fascinating. And I find it really interesting that as a girl you wanted to find a way to make sure that your island had power and you found a way to make sure that spacecraft had power. Has any part of your training been, have you been able to give back and go home and help with hurricane damage and things like that with power, with the stuff that you’ve learned?

Concha Reid: 11:58 So that’s not the trajectory that my career ended up taking. I have gone back to the university for instance, and given talks to the university students and done some special talks during science nights and things like that. But when I got an opportunity to work for NASA, it was like a dream come true. And so that’s the way, the trajectory that my career path took. But there are a lot of corollaries to an island needing to have power and a spacecraft needing to have power, because there isn’t the natural mechanism to have a huge network of transmission lines, for instance, that can naturally adapt when one area loses power, to be able to transfer power from another place that has more power to provide. So a lot of the same principles, in terms of, we got to get that system as a standalone system. We need to have the quality and reliability in the system so that it can stand alone without any maintenance, and that can last for very long periods of time without any interaction to fix something that might have gone wrong.

Ashley Hamer: 13:25 Yeah, that’s fascinating. I love those parallels. So cool. You mentioned your science teacher, did you have anyone else who was an inspiration to you?

Concha Reid: 13:38 Yeah, absolutely. I would say my parents. They were very education minded. I have seven brothers and sisters, and my mom was a nurse growing up, and my dad was a teacher, and there wasn’t a lot to go around, but the one thing that was always very clear to us was that we would all pursue a college education. That really wasn’t an option as far as they were concerned it, it was, “You will go to college, so figure out what you’re going to do,” was the message. So I do credit them for instilling in me that work ethic and the dedication that it takes to pursue lofty goals.

Ashley Hamer: 14:32 Is there anyone that you wish you had seen for inspiration?

Concha Reid: 14:37 I did not have access to any engineers when I was growing up. So I would say I think it would’ve helped navigate a difficult college career if I had had those types of mentors where I could reach back and even just, for instance, get help with my homework, for instance. I had many classmates in college who had fathers or mothers who were in technical fields that they could go home on the weekend and get help with that physics work. And I never had that, so I had to grunt it through, let’s say, no regrets though. Thing that you go through helps to shape your attitude, I feel for the future. So I think it did help me learn to rely on myself and how to figure out how to solve my own problems, so to speak. But I do think it would’ve helped a lot to have a mentor. And so as a result, I do like to give back and mentor others who are in the same situation.

Ashley Hamer: 15:59 Let’s talk about your career as a whole. So what was your career path from high school up until now?

Concha Reid: 16:09 So I graduated with my bachelor’s degree from the Louisiana State University in electrical engineering, where I did try to emphasize more on taking courses in power systems. Then I went to the Virginia Tech, or Virginia Polytechnic Institute and State University, Virginia Tech for short, in Virginia, where I really, really developed my passion for engineering and I focused on power systems as well as alternate energy sources and just really fell in love with that field. So I actually also met my husband. We actually got married, both of us when we were in graduate school and we had our first child.

16:58 So here I took a little bit of a non-traditional path. We decided it was best for our family for me to take a few years off and raise our family. So I do say it is possible for you to take a non-traditional path and still have a very successful science and engineering career. I reentered the workforce about five years later, where I took my job at NASA, and I immediately got tons of responsibility, which helped me to be a very independent researcher and an independent thinker. And I’d say the rest is history.

Ashley Hamer: 17:46 So many women talk about taking time off can get you out of… Once you’re out of the workforce, it’s really hard to get a job again. And there you took five years off and then you got a job at NASA. How did that work? Tell me about that experience.

Concha Reid: 18:05 So I completely agree. I also had those fears, and I remember telling my husband at times, “Nobody’s going to hire me. My degree is so stale,” those kinds of things. But I saw the job opening. It was the perfect fit. I knew I could do the work. When I went in there to the interview, I was just honest and I knew I could do the job. So my preparation, there was no denying that I was ready and eager and capable of doing the work. And I think in the end, that’s what the interviewer saw in me.

Ashley Hamer: 18:53 Wow, that’s so inspiring. That’s a great story, love that. What do you think the biggest hurdle was to you being here?

Concha Reid: 19:02 I would say hands down confidence. And again, goes back to having good mentors and not necessarily being able to see what I could become. And so when you don’t see people like yourself in a role, it’s hard for you to envision that you could ever achieve that. And I do think that there’s some intangibles in having the confidence when you see people like yourself achieving things that kind of bolsters you up subconsciously, you don’t even realize that you are emulating people as you go along. And so when you don’t have those role models, or you don’t have someone who is telling you that you can do this, then it does become a mental block. And I’ve worked really hard to have the confidence to even apply for a position, for instance, psyching myself out like, “Oh, I’m not qualified. I’m never going to be able to do this particular job.”

20:20 And I read somewhere that when men apply for positions, they are forward-thinking. And obviously this is a generalization, but I did read an article that talked about how forward-thinking men are when they look at a job posting and they say, “Oh, I could do that. I could do that, I could do that.” Whereas when women look at a job posting, we look at it and say, “Well, I don’t think I’ve done this yet, and I don’t think I’ve done this yet.” And we don’t imagine things where I have done this, but I’ve just applied it in a different way. And innately it prevents women from pursuing certain types of jobs, because we don’t think we’re qualified. And I would probably say that that same corollary probably can exist among certain underrepresented groups as well.

Ashley Hamer: 21:21 Yeah, that’s an aspect I really haven’t thought about, because I know I’ve seen job postings that say, they’re trying to fix that gender gap. And they say, “If you have 75% of the things on this list, go ahead and apply,” just to try to encourage people. But even that mindset of, I could do this versus I haven’t done this is really interesting and a good thing to remember.

21:55 What personal achievement are you most proud of?

Concha Reid: 21:59 I would say doing the work to get the European service module for Orion delivered to Kennedy Space Center. Myself and my team worked long and hard for several years to ensure that hardware that needed to be integrated into European service module was delivered and was on time. And our ultimate achievement was getting those first two European service modules delivered to Kennedy Space Center safely so that they can be integrated with the rest of Orion. It is something that I can say I never thought I would be able to be a part of, much less orchestrate. And so I’m very proud of that.

22:49 I’m also actually proud of all of the work that I’ve done at NASA early in my career and just working. Nothing is done as a silo. We are very much team focused and team oriented, and we solve complex problems every day. So there’s those shining moments where you can say, “Yeah, this one thing was a really big thing.” But I would say all of the work that we do builds up to those really special moments. And even if I may be the one that’s tasked with this particular shining moment thing, there’s so many people that have also contributed to making sure that that moment happens. And so I guess I’m just very proud of all of the things that I’ve done throughout my career.

Ashley Hamer: 23:49 That’s great. And that’s a great attitude to have. And then what do you see as one of the biggest challenges in science today?

Concha Reid: 23:56 Oh, wow. Well, from my NASA’s perspective, I would really love for us to learn more about the origins of life. I would love to, for some of the work that we’re doing in the inner planets. We have a few missions that are planned to Venus to do a little bit more exploration on go going toward the sun on that side of things, as well as we have an upcoming mission to Titan, which is one of the moons of Jupiter. I’m really looking forward to all of those discoveries that we’re going to make and how they can give us additional clues as to our origins here on earth and our existence and the origins of the solar system and the universe in general. Obviously, there are very worthwhile [inaudible 00:24:57] causes across the spectrum. I’m a little slightly biased toward NASA. I just love working for this organization and it’s served me well for these past 20 years, and I’m just so looking forward to all of the new discoveries that we’re going to make eventually.

Ashley Hamer: 25:17 And then finally, what words of advice would you have for someone who wants to follow in your footsteps?

Concha Reid: 25:23 Dream big. If you dream big about what you can achieve, then you can start to put into place the steps that it will take for you to get there. No matter who you are, no matter where you are, things are going to happen and you have to stay the course and figure out how you can continue to pursue your dreams.

Shane M Hanlon: 26:02 Well, Vicky, are you pursuing your dream of becoming a podcaster? Oh, man. If folks could see the face.

Vicky Thompson: 26:14 My thinking face. Yeah, so a dream I didn’t know I had, Shane.

Shane M Hanlon: 26:20 A dream Valen told you to have.

Vicky Thompson: 26:23 Valen told me, or Valen suggested to me. No, it’s funny. So it just made me think of the podcasts every week are out in the world and anybody can listen. And I don’t find that weird at all, but somehow, if I ever send a link to somebody specifically, that always feels so revealing and vulnerable to be like, “Please, specifically listen to this.”

Shane M Hanlon: 26:52 You should be doing that every [inaudible 00:26:53]. Get the word out there.

Vicky Thompson: 26:55 What?

Shane M Hanlon: 26:55 Get the word out there. Send it to all your friends and family.

Vicky Thompson: 26:58 Oh no, I do. I do. Every week I’m like, “Have you listened to the podcast?” And my parents are like, “Meh.” I’m like, “Listen to it now.” But no, but it’s just a funny thing. It’s out there. And that doesn’t bother me at all. But if I specifically, it’s like you specifically hand it to someone and say, listen to this thing that we’re doing, I think it’s different.

Shane M Hanlon: 27:19 Well, I do appreciate you doing it, even though it makes you a smidge uncomfortable.

Vicky Thompson: 27:24 A smidge.

Shane M Hanlon: 27:25 And I also appreciate Concha for taking time to talk with us today. And with that, that is all from Third Pod from The Sun.

Vicky Thompson: 27:34 Special thanks to Ashley Hamer for conducting the interview and to NASA for sponsoring the series.

Shane M Hanlon: 27:40 This episode was produced by Jason Rodriguez and me, with Audio Engineering from Colin Warren and artwork by Karen Romano Young.

Vicky Thompson: 27:47 We’d love to hear your thoughts. Please rate and review us, and you can find new episodes on your favorite podcasting app, or at thirdpodfromthesun.com.

Shane M Hanlon: 27:55 Thanks all, and we’ll see you next week.

27:57 All right. That is all salvageable. Cool.

Vicky Thompson: 28:09 Oh, that’s a stunning review.

Shane M Hanlon: 28:12 Salvageable.