33-Spaceship Earth: Discovering water on Earth from space

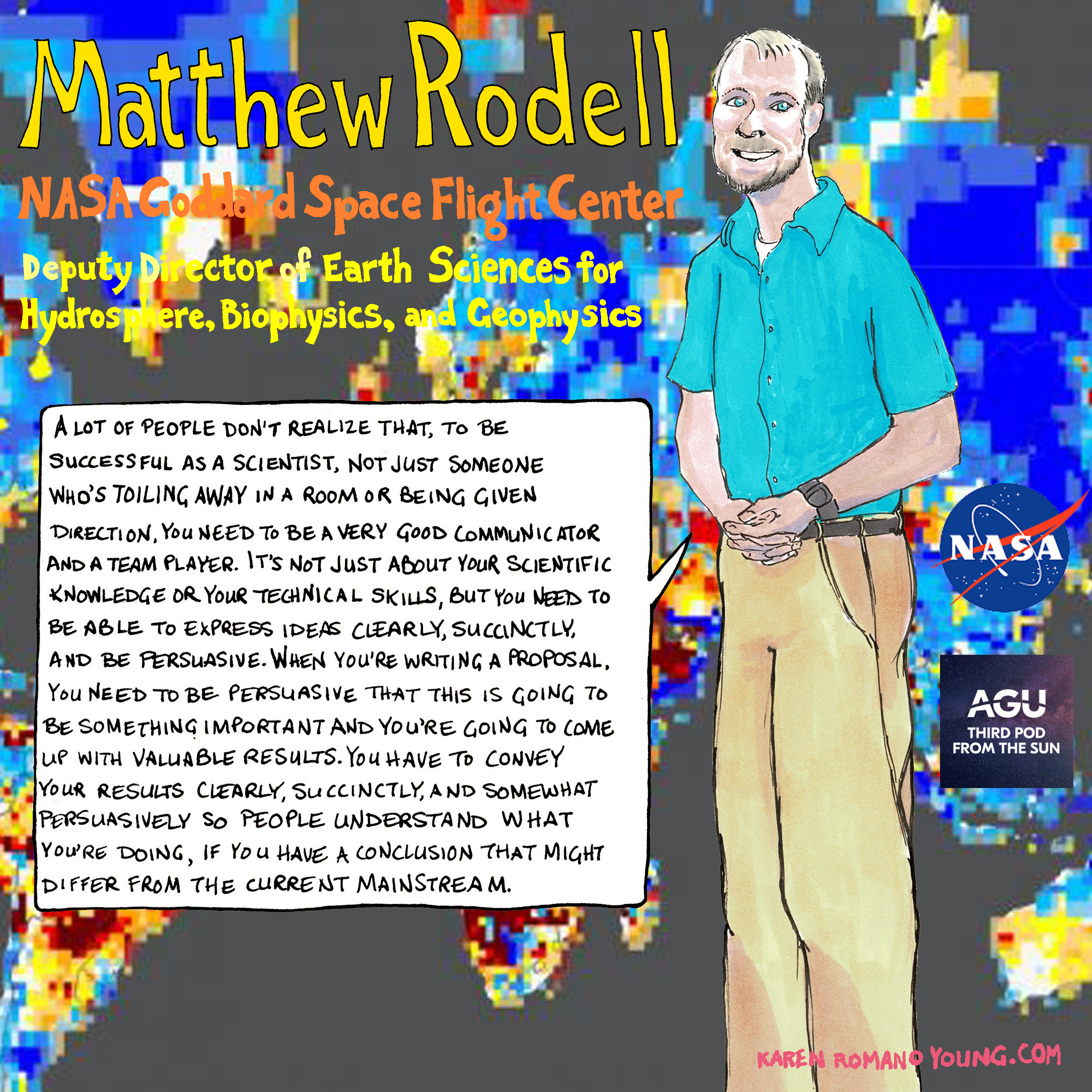

Being a Hydrologist was never on Matthew Rodell’s radar, let alone working for NASA. But he always trusted the path ahead. Now as their Deputy Director of Earth Sciences for Hydrosphere, Biosphere, and Geophysics (HGB) at Goddard Space Flight Center, he walks us through the important data being collected via remote sensing, being one of the first hydrologists to work on NASA’s Gravity Recovery and Climate Experiment (GRACE) Mission, and how a missed phone call landed him on his path with NASA.

Being a Hydrologist was never on Matthew Rodell’s radar, let alone working for NASA. But he always trusted the path ahead. Now as their Deputy Director of Earth Sciences for Hydrosphere, Biosphere, and Geophysics (HGB) at Goddard Space Flight Center, he walks us through the important data being collected via remote sensing, being one of the first hydrologists to work on NASA’s Gravity Recovery and Climate Experiment (GRACE) Mission, and how a missed phone call landed him on his path with NASA.

This episode was produced by Jason Rodriguez and Shane M Hanlon, and mixed by Collin Warren. Artwork by Karen Romano Young. Interview conducted by Ashely Hamer.

Transcript

Shane Hanlon: 00:00 Hi, Vicky.

Vicky Thompson: 00:01 Hi, Shane.

Shane Hanlon: 00:03 Today we are talking about rain.

Vicky Thompson: 00:05 Okay.

Shane Hanlon: 00:06 Vicky, I know I’m already starting off strong. So what think of when you think of rain, whether as a constant or a specific experience or what-

Vicky Thompson: 00:19 Oh, sure.

Shane Hanlon: 00:20 What are your feelings?

Vicky Thompson: 00:22 What are my feelings about rain? I don’t like it.

Shane Hanlon: 00:25 Okay.

Vicky Thompson: 00:29 I don’t know. It’s very hard for me to be in the rain and not just get sopping wet, no matter what amount of rain, somehow. I don’t like umbrellas-

Shane Hanlon: 00:39 Oh.

Vicky Thompson: 00:40 So I’m just always walking through the rain and soaking wet.

Shane Hanlon: 00:44 It’s a classic case. You have a raincoat on but then the bottom of you is probably completely wet because we don’t actually … For some reason, I feel like as a society we don’t cover the bottoms of us but we’ll put raincoats on. You know what I mean? There’s like no-

Vicky Thompson: 00:55 Isn’t that funny?

Shane Hanlon: 00:56 It is weird, right?

Vicky Thompson: 00:56 That’s very funny. I only recently got a raincoat. I would just be-

Shane Hanlon: 01:04 So it’s your own fault that you don’t like the rain.

Vicky Thompson: 01:06 It’s my own fault. So when I was younger my dad and I would go to car shows all the time and swap meets. My dad would sell motorcycle parts at swap meets. So we would spend the weekend just out in the air in a parking lot, right, doing this. So I feel like if it rained you were just wet, right? So you’d just be wet to the bone. It’s my life now.

Shane Hanlon: 01:32 It stuck with you forever. I would say I’m probably more prepared for rainy environments than you are.

Vicky Thompson: 01:41 Oh, definitely.

Shane Hanlon: 01:43 I lived in Pittsburgh for quite some time, which outside of Seattle is one of the rainiest cities in America.

Vicky Thompson: 01:49 Really?

Shane Hanlon: 01:49 Yeah. It’s because all the rivers come together and everything.

Vicky Thompson: 01:53 Oh my gosh.

Shane Hanlon: 01:53 When I think of rain I actually have a pretty … As an experience or from experience perspective, a pretty positive association with it. Early in my relationship with my wife, we took a trip to Iceland, and overall the weather was really nice, but there were a few days where it was just sopping wet and awful. And we were on this quest to see a puffin because we were in a season where you would maybe see them but maybe not. And there’s one specific day where she drug me out along these beautiful cliffs in this lovely setting because there was a chance that there was a colony but it was just awful out. We had raincoats, and pants, and all that jazz, and we got completely soaked and we didn’t even see a fricking puffin.

Vicky Thompson: 02:47 Oh no.

Shane Hanlon: 02:47 We ended up seeing one or two during that trip. I look back on this trip and I have these really fond memories of it even though there were a couple moments where I was just like “Why are we doing this? This is not great.”

Vicky Thompson: 03:04 Did I make the wrong choice? So I feel like-

Shane Hanlon: 03:05 With her or the trip?

Vicky Thompson: 03:08 So I’ve been married for I feel like longer than I haven’t been married in my life at this point. We’ve been married for a really long time, 15, 16 years, something like that. I just imagine that would be the most terrible day. We would fight so much. You had a nice time.

Shane Hanlon: 03:31 Well, this was early and we recently got married so it wasn’t that sparring I guess.

Vicky Thompson: 03:34 That feeling of flying high.

Shane Hanlon: 03:41 Science is fascinating but don’t just take my word for it. Join us as we hear stories from scientists for everyone. I’m Shane Hanlon.

Vicky Thompson: 03:51 And I’m Vicky Thompson.

Shane Hanlon: 03:52 And this is Third Pod from the Sun. All right. So when I say the word hydrology what comes to mind for you?

Vicky Thompson: 04:10 Well, alluvial flow actually, now that you … Now I have an actual reason to say that.

Shane Hanlon: 04:15 We were talking about this before we got on the podcast.

Vicky Thompson: 04:17 Yes. Hydrology comes right to mind. Rivers, flowing water, moving water, right?

Shane Hanlon: 04:27 No, for me too. You are not a scientist by trading, I am a biologist by training so I am just as out there as many other folks.

Vicky Thompson: 04:37 Throwing that in my face.

Shane Hanlon: 04:37 That’s why we’re talking about rain today. And I think many folks might not appreciate a rainy day, yourself, myself included. But studying rain and systems involving water more broadly is really important, it’s a really important area of science. Today, we’re talking with a NASA hydrologist who’s using remote systems to study some of the earth’s most important processes. Our interviewer was Ashley Hamer.

Matthew Rodell: 05:11 My name is Dr. Matthew Rodell, and I’m the Deputy Director of Earth Sciences for Hydrosphere, Biosphere, and Geophysics at NASA’s Goddard Space Flight Center. I oversee an organization of about 400 scientists, engineers, and other support personnel working on basically improving remote sensing of the earth system, and particularly in the areas of the hydroelectrical cycle, the cryosphere, biospheric cycle, and other related processes. We help develop new remote sensing systems, help to put them up into space, and then make use of the data that comes down from them.

Ashley Hamer: 05:52 Nice. Remote sensing specifically, what does that do for us? What’s the goal there?

Matthew Rodell: 06:00 Well, there’s so many different processes happening on earth and you can’t measure all of them all the time using ground-based instrumentation. If you just take an example of rainfall. It’s a hugely important thing to measure. It results in the water that’s available to us as humans, and also the water that’s available to natural systems as well on the land surface. You can’t put a rain gauge everywhere on earth. And even in the US where we have a relatively dense network, there still could be miles or tens of miles between precipitation measurements, and so the only way to really make a measurement everywhere is from space. So we have some satellites in space that are looking down and measuring waves and other observables that are then used to infer the amount of precipitation happening at the surface. And this allows us to basically map global precipitation every few hours everywhere on earth. And that’s just one example. There are a lot of other examples of things we do with remote sensing in not just hydrology but biospheric sciences, oceanography, atmospheric.

Ashley Hamer: 07:10 I mean, that’s a lot of different areas. Well, speaking of science, what drew you to science in the first place?

Matthew Rodell: 07:18 Well, when I was a kid, before cell phones and all that, I mean, I was outside all the time. I mean, I was always outside the house just … I don’t even know what I was doing, just running around the woods and doing little experiments. I would catch caterpillars and raise them into butterflies or try to catch frogs or who knows what I was doing but I was always outside and so I was always sort of a naturalist without even knowing what that was. I’ve always been concerned about preserving natural resources. And so I remember doing a report in ninth-grade science class on deforestation of the Amazon. The report on the Amazon Rainforest I think was sort of a big turning point for me where I really started to focus in a particular part of science which was the environment.

08:06 When I was in college I took a class, an environmental geology class with Professor Pat Burkhart, and he had an outdoor laboratory that was associated with the class. We’d do experiences outside and it was just super enlightening. And he had an amazing respect for the earth that he conveyed to us. And I learned a lot about what happens when you recycle things, where does it really go. And what are the issues at a landfill? What are the issues at a paper plant, at a nuclear facility? Just a lot of things that were really eye-opening. And I feel like he was a mentor. And later he actually was my first hydrology professor, which is the area that I’m specializing in.

Ashley Hamer: 08:56 It’s wonderful to have good mentors.

Matthew Rodell: 08:58 I feel lucky that I had enough inspiration, and I sort of followed the opportunities that were there, and that led me where I am.

Ashley Hamer: 09:08 Well, that’s good. You mentioned a little bit about your education and career path. Let’s go back and just talk about how you ended up where you are. What path did you take?

Matthew Rodell: 09:28 Like I said, I didn’t start out thinking “Okay, I’m going to be a hydrologist at NASA,” that didn’t come until much, much later. I think along the way I just went where the opportunities were and to things that interested me. So when I was in college, I was going to be a math major in pre-med and that didn’t really work out, I didn’t like the math department. I wasn’t very good at chemistry so I just sort of changed directions and I tried several different things and eventually ended up being an environmental science major.

10:01 When I came towards the end of college Professor Burkhart was moving out of his house and several of the students, including myself, were there helping him move. And I was one of the last ones there and he asked me what I was going to do after college. And I said, “I’m applying for a job so I’m not really sure.” He gave me a card and said, “Why don’t you try this environmental company where I used to work in New Jersey?” And I did and that ended up being my first job. So I worked for a year in New Jersey for EMS Environmental.

10:28 And towards the end of that year, my future wife and I had been applying to graduate schools. A couple that we got into were the University of Colorado and the University of Texas. And we visited them both and both liked Texas. And they had a lot of money there for supporting graduate students so that seemed like a good deal. We had to make a decision. Were we going to defer for a year or were we going to go straight out there? It was a really tough decision. And I had actually been offered a promotion in my job and we just decided to go for graduate school and to go out there which ended up being the right decision because that’s when I met Jay Famiglietti and he set me on the course for doing GRACE Hydrology which has been the foundation of my entire career. I’m really lucky I made the decision when I did.

11:15 Again, sort of just following opportunities that were there. When I went to the University of Texas I didn’t know I was going to be working with Jay Famiglietti, I actually thought I was going to be doing something more like my job with groundwater contamination and that sort of hydrogeology. He steered me towards remote sensing-based hydrology which I had never even heard of before I got there but it seemed interesting, and he gave me an opportunity and I took it. Again, it was sort of the path that was given to me and not me sort of trying to steer the ship too hard. And then when I got my first job it was someone that I knew that I’d met at AGU Fall Meeting, actually. That was just sort of following the opportunity as well.

Ashley Hamer: 11:56 That’s great. I mean, I could imagine that decision between going with the job that you had just been promoted in and going to graduate school was probably a pretty big decision. I mean, what led to you making that decision?

Matthew Rodell: 12:10 My future and wife and I have been talking about what are we going to do. And we had decided that we were going to stay where we were, defer the graduate school admission, and I would work for another year, take this promotion. I got a message on my answering machine the last day when we were supposed to make the decision, and she said, “No, no, I think we need to go to graduate school, you have to do it.” I couldn’t get in touch with her so I was like “Okay, well, I guess that’s it we’re going to graduate school.” I sent the letter and said we were accepting, and I told my boss that I was going to be leaving. And then later on Jenna said, “No, I don’t know, I’m not sure, maybe that was the wrong ideas.” And it was too late. If we had cell phones back then I don’t know what we would’ve done. My life could’ve been totally different.

Ashley Hamer: 13:00 Wow. How much things change. That’s amazing. But it sounds like fate intervened somehow and you got to work with a really great mentor and you’re here now so that’s wonderful. What personal achievement are you most proud of?

Matthew Rodell: 13:17 The personal achievement I’m most proud of is raising a family of four kids. On the professional side, I think one of the things I’m most proud of is I was one of the first GRACE hydrologists. When Jay Famiglietti and I first became involved with GRACE, most hydrologists had never heard of it. Any ones that had heard of it were pretty skeptical that it would ever be useful. And so it was a bit of a risk focusing my dissertation on that topic.

Ashley Hamer: 13:53 That’s great. Tell me a little bit more about this GRACE you said.

Matthew Rodell: 13:58 So GRACE is the Gravity Recovery and Climate Experiment, and it’s a satellite mission. NASA has about 20 missions in orbit right now. Most of them are looking down and making measurements, various wavelengths of the EM spectrum, and turning those into useful observations for hydrology or for other areas of earth science. GRACE is completely different because it’s actually two satellites that are orbiting the earth together. And instead of looking down, the key measurement is the distance between the two satellites. And the reason that’s important is because as satellites orbit the earth, the earth’s gravity field is not completely homogenous. So if you think of where there’s a mountain range and there’s more mass there, and that means there’s more gravitational potential, the satellites are floating around basically in a vacuum their orbits are affected a little bit by the shape of Earth’s gravity field. GRACE, using the measurements of the distance between the two satellites along with their precise positioning basically are able to measure the perturbations of their orbit caused by variations in the gravity field.

15:07 Each month of observations can be used to create a new map of earths gravity field. And from month to month, the maps are so precise that we can see changes in the gravity field from month to month. The main cause of those changes are redistributions of mass at the surface so those would be things like ocean circulation and tides, atmospheric circulation. And then over land, it’s the terrestrial water storage so things like groundwater, soil moisture, surface water, and snow and ice. And as those are redistributed around it’s large quantities of mass. If you think of if you had a snowstorm, and there was a couple inches of snow on the ground when you add up a couple inches of snow over 100,000 square kilometers, it’s a huge amount of mass. It’s enough to perturb the orbits of satellites. We can back out based on the GRACE data basically the amount of snow that must have fallen in order to cause that change in the gravity field.

16:03 So as I said, it’s unique. It’s completely different from the other types of observations. This is why it was a little bit risky when it first launched. I mean, a lot of people thought this’ll never work. I mean, there’s no way that it can be that precise. It’s a different type of observation we’re not used to, and we had to make it work and find ways to make it useful just to open up all sorts of new doors in hydrology. It’s been amazing. So I was really lucky to get involved with it very early on.

Ashley Hamer: 16:34 It’s a new measurement based on something that was just already happening. Just like satellites were being tweaked by the gravity field and you just have to measure that, and then you get this whole other measurement. That’s so cool.

Matthew Rodell: 16:51 And all the credit to the geologists who came up with this. They’re the ones who were really were concerned with the gravity field, and magnetic field, and the shape of the earth, and that sort of thing. They said, “Hey, this might be useful for hydrology” way before the hydrologist thought of it.

Ashley Hamer: 17:05 Wow, that’s amazing. Science. And then just as one final question. What advice would you have for someone who was looking to follow in your footsteps?

Matthew Rodell: 17:17 A lot of people don’t realize to be very successful as a scientist, not just someone who’s toiling away in a room or being given direction, you need to be a very good communicator and team player. By communication, I mean, it’s not just about the scientific knowledge you have or your technical skills, but you need to be able to express ideas clearly, distinctly, and be persuasive. And that’s important for things like writing a proposal, you need to be persuasive in your writing that this is going to be something important and you’re going to come up with valuable results. Or if you come up with a result from your research, you need to be able to write that clearly and distinctly so people understand what you’re doing. And somewhat persuasively if you have a conclusion that might be … That might differ from the current mainstream or something like that.

18:10 So I think if you were in high school or college and you’re interested in becoming a scientist and you thought “Well, I’m just going to really focus on science and math classes,” I would say, “Well, I think you really need to pay attention to your English classes and make sure that you know how to write and communicate. Take public speaking classes if you have that sort of opportunity. Read books. As you read that helps you to be a better writer as well. And pay attention to people who you think are good communicators and what are they doing right.

Shane Hanlon: 18:55 Vicky, I think he might be talking about us.

Vicky Thompson: 19:00 In that, we should be paying closer attention to people that we think are good communicators.

Shane Hanlon: 19:05 No, because we are good communicators. Are we good communicators?

Vicky Thompson: 19:12 Oh, we’re good communicators. No, I think we are, I think we are.

Shane Hanlon: 19:12 I mean, I hope so because outside of this, literally, my job is to teach folks how to communicate more effectively. Hopefully, that comes through. If not on the pod then my other aspects of my professional life.

Vicky Thompson: 19:26 No, you’re a good communicator.

Shane Hanlon: 19:27 Oh, well, thank you.

Vicky Thompson: 19:30 You’re welcome.

Shane Hanlon: 19:30 Thank you again to Matthew for sharing his work with us. And with that, that’s all from Third Pod from the Sun.

Vicky Thompson: 19:36 A special thanks to Ashley Hamer for conducting the interview, and to NASA for sponsoring this series.

Shane Hanlon: 19:43 This episode was produced by Jason Rodriguez and me with audio engineering from Colin Warren and artwork by Karen Romano Young.

Vicky Thompson: 19:52 We’d love to hear your thoughts so please rate and review us. And you can find new episodes in your favorite podcasting app or at thirdpodfromthesun.com.

Shane Hanlon: 20:00 Thanks all, and we’ll see you next week.

Vicky Thompson: 20:08 We’d love to hear your thoughts so please write and rate … I read write.

Shane Hanlon: 20:12 It does say write, in all fairness.

Vicky Thompson: 20:15 Oh, boy.

Shane Hanlon: 20:15 That’s on me. I don’t know why it says write.

Vicky Thompson: 20:18 It probably always says that and I just don’t read it.

Shane Hanlon: 20:21 I’ve been literally copying this over for weeks now. It’s always said please write and review us.

Vicky Thompson: 20:26 Oh my gosh, okay. The first time I’m actually paying attention. Okay. We’d love to hear your thoughts so please rate and review.

Shane Hanlon: 20:36 This is-

Vicky Thompson: 20:36 We’d love to hear your thoughts-

Shane Hanlon: 20:39 Oh, wait, no-

Vicky Thompson: 20:39 What?

Shane Hanlon: 20:39 No, no. Go ahead. I’m just messing up now.