E4 – Alvin and the Ocean Deep

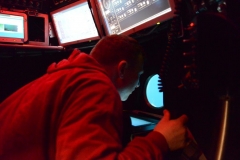

Here’s Adam Soule inside Alvin, diving to 3,800 meters (12,500 feet) on the Mid-Atlantic Ridge.

Credit: Woods Hole Oceanographic Institution.

The ocean floor is a deep, dark, cold, scary place filled with terrifying creatures and scorching fissures where boiling magma emerges from Earth’s crust. So what’s it like to be a scientist whose job it is to study these dangerous things up close and personal?

In this episode, Adam Soule of Woods Hole Oceanographic Institution describes his experiences descending to the seafloor in the human-occupied submersible Alvin. Listen to Adam describe the painstaking work of documenting every sea creature he observes on the ocean floor and the sense of awe he feels when he goes somewhere no human has been before. Finally, find out how scientists perform basic bodily functions while crammed inside a sub the size of a minivan.

Learn more about Alvin and ocean bottom research on the Woods Hole website and watch videos of Alvin’s dives on the Woods Hole YouTube page.

This episode was produced by Lauren Lipuma and mixed by Tori Kerr.

Episode Transcript

Shane Hanlon: Hi, Nanci.

Nanci Bompey: Hello, Shane.

Shane: (laughs) All right. So, I wanted to ask you, what’s one of your biggest fears?

Nanci: So, this is kind of an odd one, but one of my biggest fears is bologna.

Shane: (laughs)

Nanci: I really hate bologna. I kind of hate all lunch meat, but generally bologna is the top of the list. If it came near me, if I had to eat it, um, I would not be happy. I’d probably throw up and run away. What about you, Shane? Something more normal probably.

Shane: (laughs) I think everything’s more normal than bologna. Um, one of my biggest fears I guess is maybe- maybe of drowning actually. But … So, I’ve never been scuba diving, um, but I have been snorkeling. And I really enjoy it, but those first few minutes of being under water and feeling like the water against me and breathing water and that compression, it scares the crap out of me. I can’t imagine scuba diving or being, I don’t know, under water in a sub or something like that.

Nanci: Or if someone were throwing bologna at you underwater in a sub.

Shane: (laughs) So, yeah. I guess I wouldn’t be … uh, I probably wouldn’t be too useful if the, uh, the premise of the movie Waterworld ever came to be or something. Welcome to the American Geophysical Union’s podcast about the scientists and the methods behind the science. These are the stories you won’t read in a manuscript or hear in a lecture. I’m Shane Hanlon.

Nanci: And I’m Nanci Bompey.

Shane: And this is Third Pod from the Sun …So, it turns out that I can’t even handle being a few inches underwater, but I know a lot of scientists do work miles and miles down. Uh, our producer, Lauren Lipuma, actually talked to one recently.

Lauren: Hey, guys.

Nanci: Hey, Lauren. So, what do you have for us?

Lauren: So, last year when I was attending one AGU’s Chapman Conferences I met Adam Soule who has the coolest job title ever. He’s the Chief Scientist for Deep Submergence at Woods Hole Oceanographic Institution in Cape Cod.

Shane: (laughs) What does that even mean?

Lauren: You know, it … I’m not really sure, but I think what it means is he’s pretty much the chief scientist for all the research that Woods Hole does on the bottom of the ocean. So, his work involves using different kinds of underwater vehicles to explore the ocean floor and learn about volcanic eruptions that happen underwater.

Shane: Okay. So, ocean floor. But, how exactly do they get down there?

Lauren: Well, actually the first thing they do is they send out, um, an AVU, which is basically a drone that swims underwater to make a map of the sea floor. And those maps tell them where they might want to go to find interesting stuff. So, then what they do is they go out on a big research ship, and they explore the area with a remotely operated vehicle, or ROV, called Jason. And Jason is basically a big robot that’s tethered to the ship through fiber optic cables. Has these big titanium claws that the scientists can manipulate from back on the ship. They can pick up rocks or samples or anything else that they want to take back to their lab and study further.

Shane: Okay. But, what kind of things do they actually see down there?

Lauren: Well, actually Adam was telling me one time they were exploring Havre Volcano, which is this underwater volcano, um, off the coast of New Zealand that’s really explosive. And they were there and they saw something really weird.

Shane: All right. And just by the way, we recorded this live at AGU fall meeting, so you might hear some background noise.

Adam Soule: We went down there and it was one of the first times that anyone has been able to see the products of a submarine arc eruption shortly after it happened. And we had made a map of the area with the AUV and saw that the sea floor was really bumpy, and I thought it was because we had crappy data. And we went down there and every single bump was a giant block of pumice the size of a truck. And I had never seen anything like it before, and it was, you know, truly kind of blew my mind.

And those experiences that- that blow your mind because you’re seeing something you didn’t know, uh, was there or was gonna be there, that’s- that’s kind of routine in the deep ocean. I mean, you know, you find … You come across a hydrothermal vent that no one- no one knew was there, or a unique volcanic feature, or a kind of fish that’s never been seen before. I mean discoveries are- are routine in this place that we haven’t explored nearly enough.

Lauren: Actually, one of the cool things that Adam was telling me about that eruption was that it produced a raft of pumice that was so large people could see it from a passing plane.

Shane: A raft of pumice.

Lauren: Yeah. It’s just like that pumice rock they saw on the ocean floor, but the volcano basically belched up a huge piece of it that was so big people could see it from a passenger jet flying overhead. And eventually the raft broke up and, you know, circled around the ocean. But, it was the biggest thing, piece of pumice that they’ve ever seen.

Shane: Oh man. That’s- that’s impressive. Um, but you were- you were talking about this- this ROV, this remotely operated vehicle. How do they manipulate that?

Lauren: So, the ROV is down on the ocean floor and the researchers are all back on the ship. And it takes a whole team of people to collect samples with Jason.

Adam: First of all, you’re inside a control van. There’s a pilot, a navigator, and an engineer, and you’re in kind of basically two container vans hooked together. It’s dark, it’s cold, and there are video screens everywhere. There’s, you know, maybe 20 screens or more, and some of ’em are showing the video cameras that are on the vehicle, which … of which there are multiple and pointed in different directions. Some of ’em are showing just a picture of the wench on the ship to make sure that it’s turning, you know, at the right rate. Some of them are showing the- the back deck to make sure no one is in a- a hazardous position.

And it’s, uh, it’s a real challenge to be able to assimilate all that information in real time and- and have a … your eye on the big picture. So, you need someone who’s directing the dive, uh, telling the pilots where to go and what to sample. You need someone who’s always watching the video and documenting everything they see. We see a fish over here. We see a rock over here. And then …

Lauren: Like do they really document like every rock?

Adam: Uh, well maybe not every rock, but depending on what they’re doing you- you’re not gonna get back to the same place on the sea floor multiple times very often. Often times that’s gonna be the only time you’re there, so you want to make as many observations as you can. And that’s why we usually have one or two people dedicated just to saying, you know, there’s lots of shrimp right here. There’s no shrimp over here. No one’s gonna go back there, but someone can use the video and the observations that you made for their science questions.

So, um, you are documenting as- as much as you can. And we try, you know, to make it as easy as possible instead of, you know, writing out, “There are seven shrimp,” there might be a button you can push to say, “Shrimp, shrimp, shrimp, shrimp, shrimp.” And that’s why there’s enough people in that van to kind of separate the tasks out. So, someone saying … looking at the map saying, “We want to go here next. We need to go, you know, east 400 meters.” And someone else saying, “Shrimp, shrimp, shrimp, shrimp, shrimp, shrimp.” And then someone else, you know, documenting, “We collected a sample and it went into this box on this side of the basket.” And when you’re down there for three days you really have to have people focused on their task.

[b-roll audio]

Adam: After a while you become like a- like a little robot. You go in and you, “Shrimp, shrimp, shrimp, shrimp,” and go here, go there.

Lauren: (laughs)

Adam: Um, and the value is immense.

[b-roll audio]

Shane: All right. But, all I could think about is shrimp, shrimp, shrimp, shrimp, shrimp.

Nanci: Please … please stop. Yeah, no. Please, Shane. Don’t. (laughs)

Shane: Fine. Fine.

Lauren: I’m gonna go ahead and change the subject here.

Nanci: That’s probably a good idea. So, what else does Adam do down there?

Lauren: Uh, so the coolest thing that he gets to do is he gets to go down to the sea floor himself in a human occupied submersible, or HOV, which is called Alvin. And he gets to experience all of that stuff firsthand. And Alvin is not the first submersible that people ever designed, but some pretty cool engineering went into it.

Adam: One of the great, uh, advances with Alvin was situation called syntactic foam. So, syntactic foam are tiny glass spheres embedded in epoxy. So, hollow glass spheres. So, they are using air, but the individual buoyancy pieces, these glass spheres, are so small that they’re- they’re very resistant to crushing. And they’re also embedded in epoxy to help distribute the load of that pressure. And so, the stuff is really heavy, but it floats. And so, you have to use a- a lot of it around the sub, and that’s why it goes from the size of a mini van to the size of a bus or a small school bus. Uh, is … a lot of that’s taken up by what you need to float basically.

Nanci: So, how long has Alvin been around?

Lauren: Alvin was commissioned by the Navy back in 1964, but it’s not the same sub today that it was then.

Adam: You know, it’s been around for 50 years, but every five years or so it’s totally stripped apart and put back together. And about, uh, four or five years ago it went through that process, but also a major upgrade at the same time. So, the main part of Alvin, the kind of the most critical piece is a titanium sphere that the people go inside. So, it’s a- it’s a very big sphere. It’s made of thick titanium so it can withstand the pressure at the bottom of the ocean. And this new sphere has a couple of major improvements from the old one.

One is that it has more windows or view ports as we call them. The- the real kind of exciting part of Alvin and- and one of the benefits of that vehicle is to have human eyes and brains looking at the three-dimensional sea floor. So, the more opportunities you have to look out and see what’s there, the better. And it’s also a little bigger and a little more comfortable. So, even a, you know, pretty tall person can stand up in the submarine and stick their arms out and not touch anything.

So, uh, there’s quite a bit of room in there. Um, but it’s also packed with equipment. You know, everything, every computer, every bottle of oxygen, every piece of safety equipment has to go inside that sphere with you. It’s fairly spacious, but it’s also a tight squeeze.

I’ve talked to a lot of people who- who said, “I would never go in Alvin. I’m way to claustrophobic.” And, um, the reality is you hardly even know you’re in a small space ’cause you’re pressed up against the view port the entire time. It’s such an amazing experience to be able to see not only the bottom of the ocean, but the place where- where your scientific research is conducted.

Lots of scientists have that opportunity, you know, that they study a volcano on land or they study a prairie or they study a river. They can immerse themselves in it. That’s not a common thing for- for the deep sea. If you’re studying the animals that are down there, the rocks that are down there, or the chemistry of the water, um, it’s a pretty special opportunity to- to be able to immerse yourself in that environment.

Lauren: So, is there anything left from the original Alvin that’s on the new, brand new upgraded Alvin today?

Adam: Absolutely not. Unfortunately. It would be cool if they kept one screw.

Lauren: Yeah.

Adam: But, uh, no. It’s all been replaced.

B-roll Audio Recording:[inaudible 00:11:44]

Alvin roger, your checks. Your launch altitude is 1365 meters, 1365 meters. You have permission to dive when the swimmers are clear.

Roger [inaudible 00:12:05]

Nanci:Yeah. So, I was wondering, what’s a typical like, um, inside this tiny sub under the ocean?

Lauren: It’s actually a pretty long day for them. They’re in the sub basically from sun up to sun down.

Adam: The dive is gonna start near first light, and it’s gonna end at dusk. They … Uh, it’s safest to launch and recover the submarine when it’s light out because it involves, uh, people swimming in the water. So, you’ll go out to the submarine and you’ll get inside and they’ll close the hatch. Uh, there’ll be a couple, uh, people standing on top of the sub as it gets lifted up on an A frame. And an A frame is kind of like a- a little bridge that can lift up and rotate out over the ocean. So, that’s holding Alvin, and it rotates out over the ocean and lowers the sub down. The people on top, they kind of unhook it, and then they dive off the submarine down into the water.

B-roll Audio Recording:Alvin is submerged. [inaudible 00:13:04]

Adam: And once they’re in the water, um, Alvin has a basket sitting out in front of it, or a porch that sits out in front of it. And that’s where you put all your samples and bring down all your instrumentation. They unhook that. Uh, you can see ’em out the view port. If you look they’re swimming down and around the sub.

Lauren: Mm-hmm (affirmative).

Adam: And then you start, uh … you get the clearance from the ship and you start to descend. And when you’re, uh, up near the surface the- the blue of the ocean is one of the most beautiful colors you can- you can see. It’s this vibrant bright blue, and as you sink down it gets darker and darker and darker. And, you know, after a couple hundred meters it gets quite dark. But, uh, instead of, you know, being boring you start to see lots of bioluminescent, uh, animals, and if you flash the lights of the sub they flash back at you, which is pretty awesome.

And as you go down, um, there’s actually work to be done. You’re talking with the pilot. What are we gonna do first? What are we gonna do second? You know, there’s two scientists in there. What are you gonna do? What am I gonna do? How does the … how do the video controls work? So, you do a fair bit of kind of, uh, acclimatizing yourself to the sub. And then you’re looking out the window because you want to see the sea floor. At least for me I want to be the first person to see the sea floor. And, uh, then you see it.

The sub, uh, kind of gets trimmed, you know, so it stays level. And then you start working. You know, you can be down … uh, a dive can last nine hours. You might spend, uh, six or seven of that working on the sea floor. And honestly, that goes by in a flash. I mean you are- are kind of completely focused on the task at hand for those hours and you don’t even notice the time going by.

So, you have so many things to do. You have to control the camera. Make sure it’s pointed in the right direction and focused. And each scientist has a camera they are controlling. You’re taking notes. You’re directing the pilot on where to take samples. You’re discussing as a group where to go next.

And then at some point the pilot’s gonna say to you, “Look, we gotta go to the surface. We’re out of power,” or “We’re out of time.” And you start to rise up. And then you kind of breathe a sigh of relief. And you’re like, “Oh my gosh. I haven’t peed in seven hours.” And then, you, uh, wrap things up. You think about what you saw. You- you make some notes. And then you get to the sea surface. You get picked up and put back on the ship and, uh, get ready to do it again tomorrow.

Lauren: So, how do you go to the bathroom in Alvin or do you not? Like what if you just have to go?

Adam: That’s a- that’s a personal choice. I definitely go to the bathroom in Alvin. I don’t … Because like a day without coffee would not be a good day. So, I have to have some coffee. And so, uh, we have equipment for that. We have HREs, which I mean …

Lauren: I don’t know what that is.

Adam: Human range extenders. It’s a bottle. It’s just a bottle that you pee in.

Lauren: (laughs)

Adam: And there’s, uh, there’s a boy version and a girl version. And the easiest thing to do is just say, “I’m gonna pee.” Everyone looks out their window, which is not a hard thing to do, and, uh, you take care of it. But, if you’re, um, more modest you can, you know, hang up a sheet or something like that. And, um, I think it’s the best choice to try and keep it to number one if you can, you know.

Lauren: Yeah, yeah.

Adam: (laughing)

Nanci: So, Shane, have you ever used a human range extender?

Shane: (laughs) Uh, I don’t know about a- an official, uh, certified human range extender, but there’s probably some stories about Mountain Dew bottles back in high school somewhere.

Nanci: Very, uh … yes. Very frat boy of you.

Shane: (laughs) Anyways, so Adam is an old pro by now both scientifically and bodily function-wise. Uh, but what happened on his first time down in the sub?

Lauren: Yeah. He- he told me about that. He actually had a little bit of a scare his first time.

Adam: You’re in this enclosed space. I mentioned you close the hatch. That’s the air that you have for the rest of the day. And, uh, we breathe in, um, oxygen, breathe out CO2. We also breeze out- breathe out a lot of water vapor. And the- the titanium of the- the personnel sphere is cold, so you get a lot of condensation in there.

And so as we were going down with a very experienced scientist and a very experienced pilot in my very first time, um, I was looking out the view port intently, breathing heavily on it ’cause I was so excited, and all this water started to collect at the bottom. And I was like, “Listen, I don’t want to alarm anyone, but I think we have a leak over here.” And all they did was take a box of, you know, like paper towels and throw it at me and said, you know, “Wipe it up. You’re fine.”

So, Alvin, you know, 50 years plus has had almost five thousand dives and has a perfect safety record. It’s … I feel safer, you know, diving in Alvin that I do driving in a car so that’s- that’s a good thing.

Lauren: That is good. So, what was that first dive like for you?

Adam: I … You know, it’s hard to describe what it’s like. I think that- that I can tell you what the environment looks like. You know, you can’t see all that far. You can see 10 meters or so. The colors are really often times very muted because, you know, it’s- it’s a completely dark environment. You don’t need the brightly colored fish of coral reefs. You know, everything’s kind of white and- and pink and gray.

Um, and but- but what struck me the most was that I was the first person to see that spot on planet Earth. And it felt really special to do that. And, you know, frankly that feeling, uh, wore off pretty quickly because I had to get samples. You know, this was for my research and I needed to get those samples and make those observations. But, there was certainly a moment in there where I felt just so fortunate. And, you know, I can only imagine what, uh, you know, the Apollo astronauts felt like when they- when they stepped out onto the Moon. It’s just, uh, it’s really unique for a human to be somewhere on this, uh, planet or somewhere else that no one has- has, uh, put their foot down before.

Lauren: What’s the coolest place you’ve gone to?

Adam: I guess what I would call my most exciting dive in- in Alvin, and it was a dive with, uh, Bruce Strickrott, who’s currently the manager of the Alvin program, and he was a pilot at the time. And we were at the Galapagos spreading center. And that’s the place where Dr. Bob Ballard first discovered hydrothermal vents back in the 1970s. And so we were looking for hydrothermal vents and were cruising across the sea floor, and it was all black lava flows. And we didn’t quite know where we were going to find these vents. And we found a big crack in the sea floor, and that crack is kind of marked where the plate boundary was, where the two plates are diverging. And so we started to follow it. And as we got further along we started to see, uh, little Serpulid worms. These are white worms, and they were stuck to the walls. And we were like, “Oh, this is looking better and better.” And then we started to go a little further and the water started to get hazy. And that’s, uh, kind of a sign that maybe there’s some venting nearby.

And we came out of this crack and we saw this massive black smoker covered with these beautiful Riftia tube worms. They’re kind of meter high worms with a white case and a beautiful red plume sticking out the top. And it was, you know, one of the most gorgeous things I’ve ever seen. And I felt like, you know, we had really discovered it.

Now, in a few minutes of driving around we- we looked around and we saw this stack of steel weights on the sea floor. Alvin goes down with a bunch of extra weight that helps it sink to the bottom, and then it drops those weights when it needs to come back to the surface. So, we saw some steel weights. They said 1977 on them. They had it written on them. That was the year that the black smokers were discovered. Uh, so it happened to be a place that people had been before, but it was special to me because it was one of … it was the place where kind of these black smoker vents were discovered.

B-roll Audio Recording:Copy that, Alvin. Stand by for [inaudible 00:21:30]

Standing by. [inaudible 00:21:38] I read you loud and clear.

Adam: Yeah. That’s us sending out interrogations on the transponder to the sub. And then the sub has a beacon on it that responds. Uh, every once in a while, every 30 seconds you’ll hear the kind of the modem sound. Uh, that’s actually the transponder sending out, uh, information to the sub. Uh, like location of the ship and, uh, other stuff like that. And then we receive information back from the sub’s transponder like it’s depth and altitude and stuff like that.

Nanci: This all sounds so cool, but what are they actually learning from all this?

Lauren: So, they’re learning a lot about eruptions and how eruptions happen on the sea floor. But, some of the most interesting things they’re learning actually aren’t about volcanoes.

Adam: Every place in the ocean that you have magma stored in the crust you have hydrothermal circulatioN about that. Everywhere you have hydrothermal circulation, fluids moving around through the crust and the rocks, you have animals that are taking advantage of those fluids. And I think we- we’ve come a long way in understanding what those connections are, um, but we’re learning more all the time.

Lauren: So, how many days do you think you spend at sea total in your career?

Adam: Oh, let’s see. Uh, so how many days have I spent at sea? Uh, it’s gotta be, um, somewhere between a year and two years.

Lauren: Wow.

Adam: I mean I’ve been doing this for, you know, 10 to 15 years and maybe a month or so a year at so. And so it- it’s added up, but, uh, um, and- and it’s … you know, it’s hard to- to, you know, be away, but on the other hand it’s so much fun to be out there and making discoveries and- and the like. So, I would, you know, I still love going to sea.

Lauren: How many times have you been down in Alvin?

Adam: I don’t know the exact number, but it’s in the order of 10 to 20 times. So, probably 15 times in Alvin, and, uh, I would take the opportunity to dive in that submarine any chance I got. There are some people, um, pilots of the sub for example, that have had, you know, a thousand dives in Alvin or more. And I don’t even think for them that they get tired of it. I mean it is, you know, truly one of the coolest experiences you can have as a scientist.

You know, the other thing that’s- that’s I think pretty neat about the sub is that it’s a facility for research. It’s an asset that’s been developed to help people do science. But, it’s also been available for other uses. And- and one of the first things that Alvin did was help recover a hydrogen bomb that was lost in the Mediterranean.

Lauren: Wow.

Adam: The crew of Alvin has helped out in search for the voyage data recorder of, uh, the El Faro that sunk. The crew was just own helping look for that, uh, lost Argentinian sub, the San Juan. So, um, these are … you know, we- we often have, uh, difficulty conveying how the basic research of scientists, uh, helps people or- or is relevant to our society, but just the tools that we’ve developed, um, in many cases can be instrumental in helping, uh, address some societal needs like that.

Shane: Well, so is anyone up for exploring the ocean deep to find bombs?

Lauren: No. But, I would really like to use Alvin to go find some narwhals.

Nanci: Oh.

Lauren: (laughing)

Shane: All right, folks. That’s all from Third Pod from the Sun.

Nanci: Thanks to Lauren for bringing us this story, and of course thanks to Adam for sharing his work with us.

Lauren: And thank you to Woods Hole for providing us with imagery and audio. And if you want to see more of Adam’s adventures in Alvin go to the Woods Hole website at www.whoi.edu.

Shane: This podcast is also produced with help from Josh Speiser, Olivia Ambrogio, and Caitlyn Camacho. And thanks to Tori Kerr for producing this episode.

Nanci: AGU would love to hear your thoughts on our podcast. Please rate and review us. You can also find new episodes at your favorite podcasting app or at thirdpodfromthesun.com.

Shane: Thanks, all, and we’ll see you next time.