E11 – Deep Sea Drilling with Dawn

The ocean floor stores a vast amount of information about Earth and its history. Volcanic rocks that make up most of the seafloor tell scientists about the composition of Earth’s interior, and the sediments lying on top of those rocks document what conditions were like when they were laid down millions of years ago.

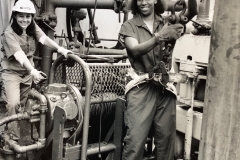

Scientists access this record of Earth’s past by drilling and extracting cores – long cylindrical samples – of the layers of rock and sediment. To do this, researchers spend weeks aboard a scientific drillship, anchored in place, braving the harsh conditions of the sea. Early in her career, oceanographer Dawn Wright, Chief Scientist at the Environmental Systems Research Institute (ESRI), spent several years as a marine technician aboard the drillship JOIDES Resolution, supporting ocean drilling operations all over the world.

In this episode, listen to Dawn describe her experiences during the months she spent anchored in the freezing Weddell Sea off the coast of Antarctica and hear how support ships have to “lasso” icebergs to keep them from damaging the drillship while it’s anchored. Ahoy, matey!

This episode was produced by Lauren Lipuma and mixed by Adell Coleman.

Episode Transcript

Shane Hanlon: Hi, Nanci.

Nanci Bompey: Hey, Shane. Welcome back-

Shane Hanlon: Thank you.

Nanci Bompey: … from vacation. Were you on a cruise, by any chance?

Shane Hanlon: I was not on a cruise, actually. I was actually in the desert, hiking the Grand Canyon rim to rim-

Nanci Bompey: Oh, sweet. Awesome.

Shane Hanlon: … which is very different. But I actually have been on a cruise before. I went with my family for, what was it, my parents’ 40th wedding anniversary? The whole family went. It was actually lovely. For all the things that people say about cruises, I actually had quite a lovely time.

Nanci Bompey: Where’d you go?

Shane Hanlon: Bermuda.

Nanci Bompey: Oh, nice.

Shane Hanlon: Yeah.

Nanci Bompey: Yeah. I have never been on a cruise.

Shane Hanlon: No?

Nanci Bompey: However, you know Richard, my boyfriend, is really into metal music. There is a metal cruise.

Shane Hanlon: The gears in my head were turning so quickly. I’m like, “Where is she going? Where is she going?”

Nanci Bompey: Yeah, it’s like five days of just bands, constant bands, metal. It’s called, like, 70,000 Tons of Metal or something.

Shane Hanlon: Who puts it on? Is it like a Royal Caribbean metal cruise?

Nanci Bompey: No. I don’t even know. I don’t even know, but I’ve somehow sort of agreed to this. I’m not sure if I really want to go through with it, though.

Shane Hanlon: Wait, you’re going?

Nanci Bompey: No, we haven’t signed up, but I’m like, “Eh, it’d be fun,” like maybe for his 50th birthday or something.

Shane Hanlon: When does this happen? Where does it go?

Nanci Bompey: It goes to the Caribbean or something. The cool thing is, you can be behind the scenes of the music, because you’re just chilling on the boat with the bands, man.

Shane Hanlon: If this ever happens, we are revisiting this, and you are taking so many pictures, because this is going to be amazing.

Nanci Bompey: Anyway, it’s very different from the type of cruise that scientists go on, however.

Shane Hanlon: Yeah, there is actual setup to this. I mean, you have been on a research cruise, right?

Nanci Bompey: Yeah, I did a very short one, like off the coast of Oregon, which was definitely awesome, definitely. Our episode this week we talk to someone who has been on many cruises, research cruises.

Shane Hanlon: Yes. Yes, they have. Probably not a metal cruise, though. [music] Welcome to the American Geophysical Union’s podcast, about the scientists and the methods behind the science. These are the stories you won’t read in the manuscript or hear in a lecture. I’m Shane Hanlon.

Nanci Bompey: And I’m Nanci Bompey.

Shane Hanlon: This is Third Pod from the Sun. All right, so we’re talking about vacation cruises, but there are different types of cruises that scientists do. Right?

Nanci Bompey: Yeah. I mean, they call them cruises, but they’re work. I mean, yes, they have a little bit of fun-

Shane Hanlon: A little fun.

Nanci Bompey: … but it’s mainly work.

Shane Hanlon: Mainly work, yeah.

Nanci Bompey: Mainly work. Research cruises they call them.

Shane Hanlon: Right. We’re talking about this, so we’re going to bring in Lauren Lipuma, who talked with a scientist who does, or at least in the past has done many research cruises. Hi, Lauren.

Lauren Lipuma: What up!

Shane Hanlon: What do you got for us today?

Lauren Lipuma: A couple months ago I met Dawn Wright. She’s a scientist. She works at the Environmental Systems Research Institute, also known as ESRI. She’s also a professor of oceanography at Oregon State University.

Shane Hanlon: What does she do?

Lauren Lipuma: Well, right now Dawn does a lot of science policy, science strategy work, but early in her career she worked on mapping the sea floor. Actually, the way that Dawn got started in science is that she went on several … actually, many … ocean research cruises, or expeditions, I guess you could call them, with the Ocean Drilling Project, known as ODP, which drills sediment cores from the ocean floor. Their goal is to kind of reconstruct the past geologic history of the oceans.

Dawn Wright: I finished my master degree at Texas A&M University in 1986. Around that time Texas A&M was the science operator for the Ocean Drilling Program, and so they were staffing the JOIDES Resolution drill ship with staff scientists and marine technicians and facilitating all of the operations, the logistics, and so forth with the science parties going out on those ODP cruises.

When I finished my master degree, I got hired by ODP as a marine technician, and it was very exciting for me, because my first cruise was Leg 113, which went to the Weddell Sea, Antarctica. I was out with that science party for two months in late 1986 and into 1987. I had only been to sea once before on a student training cruise in the Gulf of Mexico. So, to go from that to two months in the Weddell Sea in Antarctica, it just blew my mind. It was just amazing, and I loved it. I loved every minute of it. It was such a great adventure.

I ended up doing nine other cruises with the Ocean Drilling Program as a technician. Then I decided to go back to school for my PhD. So, I had about three years of going to sea with ODP, and it was awesome. Each of those expeditions, each of those cruises, was amazing, but the Antarctic ones, I think, were the most memorable.

The Ocean Drilling Program, and now the IODP, takes samples, cores, of sediments and rocks from the ocean floor, mainly to reconstruct the past history of the oceans. In the case of Leg 113, what we were trying to do was to reconstruct the paleo-oceanographic history of the Weddell Sea. We were looking at the past movements of the West Antarctic ice sheet, looking at processes such as ice rafting, sedimentation rates, just trying to discern what went on, particularly in the Cretaceous Period in that part of the southern ocean. So, we were getting all that information from the cores of sediments that we were able to drill at, I believe it was, nine sites.

Lauren Lipuma: How does the process of drilling an ocean core work?

Dawn Wright: It’s probably a lot different from when I was out 30-some years ago, but the general principle was, you lower this drill pipe down to the sea floor, you anchor it onto the sea floor, and you have this drill bit at the end of the drill pipe that rotates and then kicks up material as it gets deeper into the sediments. That material gets collected into a barrel that is lowered through the drill pipe, and that barrel gets filled up with that material.

When it gets filled up, then it gets pulled back up to the ship by a wire, full of that ocean sediment. There is a plastic sheath within the barrel that is extracted, and then that’s what we as technicians work with in terms of splitting that core and then running all kinds of tests on the core with the science party. The drill barrel goes back down to the sea floor to get more material as the drill pipe is going deeper and deeper into the sediment.

So, you just keep doing that over and over again until you get down to a layer where it’s just not feasible to go any deeper, or I guess it depends on the scientific objectives of that particular cruise. In our case we had nine sites to drill, so we had to spread out our time over the two months that we had at sea.

Lauren Lipuma: So, each time you get to a site, how long are you there? Take me through that process of getting down on the ship to the site and then what happens when you get there.

Dawn Wright: Well, if you want to take a core from the sea floor, you have to take into account the water depth. If you’re trying to drill in a couple miles deep of water, it takes time to get that drilling assembly, what they call the bottom hole assembly, down to the sea floor, get that all set up. Then, again, it depends on how deep you want to get, how much sediment you want to collect at that particular site. So, you may be on a site for several days to a week.

The danger there is that you’re anchored in the sea floor over that period of time. So, for us, being in the Antarctic, basically in Iceberg Alley, we had to have some type of safety support to ensure that we weren’t hit by icebergs, or bergy bits, while we were anchored in the sea floor getting our cores.

Lauren Lipuma: How do they do that? How do you have that safety?

Dawn Wright: For us, and from what I remember, we had the Maersk Master, which was a support ship that was basically there to lasso icebergs and drag them out of our way. It was a Danish ship. I’d never met a crew of sailors who were so excited about their job. They just thought that they were the best, because they were basically there to keep us from danger. They were like superheroes on the high seas.

Lauren Lipuma: Wow.

Dawn Wright: I certainly thought they were. They were awesome guys. They were really friendly. They would come over and visit us. They would send a Zodiac, or a small little boat, to come over and visit us from time to time. They were basically following us around throughout the entire two months, and they had to calculate how far away a particular iceberg was from us. Taking into account the winds and the speed at which the iceberg was traveling and, of course, its direction, they would determine when they would need to intervene.

So, when an iceberg would get into the danger zone, into this buffer zone where it might affect us, they would steam up to that iceberg. They had this huge, humongous rope. It was basically a rope that they would drop over the side right at one point of the iceberg. They would steam around, letting out the rope as they went, until they encircled the iceberg, and they would pick up that rope and then, literally, like a tugboat, tow the iceberg out of the way.

If you were on break, or you weren’t on your shift, it was really fun just to go to the side and see them in their operations, because there were so many icebergs, or bergy bits, that were in our vicinity throughout those two months that they were continuously in operation, so you could always see them towing an iceberg.

Lauren Lipuma: How long does that take?

Dawn Wright: I think, to get each of those icebergs, it took them several hours, and it really would depend on how big the icebergs were. As I was telling you before, there was this … I don’t know whether it’s in the Guinness Book of World Records, but they made a big deal about this iceberg that was approximately the size of the Texas A&M football stadium. At the time, Texas A&M, their football stadium was called Kyle Field, and they calculated this one iceberg … It could have fit inside of Kyle Field and filled out that stadium.

Lauren Lipuma: Oh, wow.

Dawn Wright: It took them many, many hours to deal with the Kyle Field iceberg.

Lauren Lipuma: So, they’re just doing this continuously while you guys are anchored there and drilling?

Dawn Wright: Yes. Yes. Now, we had nine sites that we drilled. So, during the time that we would pull up the bottom hole assembly, bring up all the drill pipe onto the deck, and move to another site, that was, of course, transit time, where they didn’t need to support us. They would just follow along and wait until we lowered the pipe at the next site and were again anchored in the sea floor. Then they would continue to just circle around us and just keep watch for the icebergs that might pose a danger to us.

Another nice little thing that happened on that cruise with those Maersk Master … with the crew: A couple of them were really into making pottery and making things just out of clay. I don’t know if they had a kiln or an oven. I don’t know how they were able to actually make little sculptures, but they took some of the sediment from the sea floor, and they created little clay penguins, and whales, and dolphins, and things, and they painted them, and they gave them to some of us as gifts. I still have my little deep sea sediment penguin. There’s picture of it on Instagram, so I can send you the link. It was so precious.

Lauren Lipuma: Yes, it’s so precious. So, you guys had such a good relationship, then, with these guys.

Dawn Wright: Yeah, yeah. They were a really happy, happy bunch.

Shane Hanlon: Nancy, you mentioned previously that you’ve been on a research cruise. What was that like?

Nanci Bompey: Yeah. Like Dawn was talking about, it was awesome. It was great. We were just off the coast of Oregon for a few days. One thing that you might not realize: Of course, you’re on there with the scientists, but there’s this whole crew … I mean, just as many folks … and they help everything get done on the ship. I mean, they couldn’t do it without them. I filmed the chef, who was incredible. He cooked a whole meal in this little galley kitchen.

Shane Hanlon: What did you do? What was your contribution?

Nanci Bompey: What did I do?

Lauren Lipuma: Yeah, what was your job?

Nanci Bompey: Social media. Tough.

Lauren Lipuma: Did you get internet out there?

Nanci Bompey: Yeah, there was internet. We were actually close to the shore enough, but the internet is pretty slow.

Lauren Lipuma: Okay, cool.

Nanci Bompey: So, that was a little tough. I helped them with the sampling by the end, just general …

Shane Hanlon: How were the waters? How was the sea? Did you get seasick or anything?

Nanci Bompey: That’s a good thing, because the whole thing was, it was a cruise in the winter off the coast of Oregon. Most times when you go out in the winter, it’s really rough. I had the patch behind my ear. But, man, there was one day when we were in the trough, the trough … I’m not going to say it right.

Lauren Lipuma: Trough.

Shane Hanlon: Trough.

Nanci Bompey: … where you’re, like, going across. A lot of people, even people who’d been on hundreds of cruises, they had to go downstairs and lay down. We were just sitting there watching a movie, just not looking at each other, not talking, not eating for, like, eight hours.

Lauren Lipuma: Wow.

Dawn Wright: I remember that for most of our drilling operations within the Weddell Sea, the seas were pretty calm. It wasn’t too stormy. The main thing that we were in danger from were these icebergs. But we had to get to our first site by leaving Punta Arenas, Chile at the southern tip of South America and going across the Drake Passage. It’s that passage of very rough seas between the southern tip of South America and then the tip of the Palmer Peninsula in Antarctica. Those were some pretty rough, stormy seas.

Basically, it was like being in a winter wonderland, because it was always cold. I remember wearing long underwear the entire time, the entire two months … not the same pair, of course. The sea life … There were lots of whales and seals, albatross, and they would come right up to the drill ship, right up to us, anchored on site. So, that was just amazing-

Lauren Lipuma: Wow.

Dawn Wright: … just to have the sea creatures come right up to us. It was great.

Lauren Lipuma: Did you ever get kind of … I don’t know what the word is, really, but sick of being out there towards the end of the cruises. You’re there for two months. Is there ever a point where you’re just like, “Get me off this boat right now”?

Dawn Wright: I never experienced that. There were a lot of people who went through that, but I just loved being out there, and I never got tired of it there. Of course, with any research cruise you’re doing repetitive tasks. Our shifts on the drill ship were 12 hours on, 12 hours off. When you’re out there for two months, there can be a lot of boredom. You’re eating the same things in the galley. The quality of food in the galley goes down. You run out of movies to watch. But none of those things bothered me. I had dreamed of going to sea as a child, and I read all of these things, like 20,000 Leagues Under the Sea, and pirate novels, other pirate books, and it was just fantastic. I never got tired of wearing the same clothes over and over again. For me it was really a lot of fun.

I just learned a lot about that culture. It’s a separate culture out at sea, and you’ve got to be very respectful of it, be respectful of the captain and the people who are senior than you. You have to have a lot of humility and be open to learning a lot and working hard, making sure that you know your role and that you can contribute and pull your weight.

I hope, for any oceanography student, that you get a chance to go to sea early and often, because there’s just nothing like actually being out there collecting the data. The people that I was out at sea with have become lifelong friends. If you can step off a ship after being at sea with someone, and you’re they’re friend, that’s pretty significant. There’s some wonderful relationships, or enemies, too, I guess, but in my case it was all positive. So, I really hope that everybody in the ocean sciences gets that experience.

Nanci Bompey: Yeah. I mean, I can totally understand what Dawn is saying. I was on this research cruise just a few days.

Shane Hanlon: I was on the research cruise.

Nanci Bompey: I was on the research cruise just a few days. I’m a real oceanographer. I mean, we had so much fun in those few days, but these guys have been going out … They’re on a big project, and these guys have been going out on cruises together for years, and they have T-shirts-

Shane Hanlon: Oh.

Lauren Lipuma: No. What do they say?

Nanci Bompey: … that they made that were commemorating different times they’ve gone out together on projects.

Lauren Lipuma: Oh, no.

Nanci Bompey: They know each other so well. They know all the music they play. They know how people act. I mean, you really get to be tight with … I mean, you’re on a little, tiny boat.

Shane Hanlon: I was going to say, you have to get along, right?

Nanci Bompey: Yeah, you have to get along, or it would be weird.

Shane Hanlon: Maybe the three of us could take some lessons from them.

Nanci Bompey: Wow, us on a research cruise.

Lauren Lipuma: I don’t think that would work very well.

Shane Hanlon: We’ll just limit it to our time on the podcast. All right, folks. Well, that’s all from the Third Pod from the Sun.

Nanci Bompey: Thanks, Lauren, for bringing us this story and, of course, to Dawn for sharing her work with us.

Shane Hanlon: The podcast is also produced with help from Josh Speiser, Olivia Ambrogio, and Liza Lester. Thanks to Adele Coleman for producing this episode.

Nanci Bompey: AG would love to hear your thoughts. Please rate and review us on iTunes and listen to us wherever you get your favorite podcasts, because hopefully we’re one of your favorites, too, or at thirdpodfromthesun.com.

Shane Hanlon: All right. Thanks, all, and we’ll see you next time.