E16 – Gunslingers of the Sea

Ocean acoustics specialist Joe Haxel, getting ready to deploy the drifting hydrophone he uses to record the ocean soundscape. Credit: OSU/GEMM Lab.

Snapping shrimp are small but mighty creatures: they’re only a few inches long but are among the noisiest animals in the ocean. The loud cracking noise they make when snapping their claws sounds almost like a gunshot, and when enough shrimp snap at once, the din can be louder than the roar of a passenger jet flying overhead.

Snapping shrimp are typically found in warm, shallow subtropical waters all over the world. But in 2016, researchers at Oregon State University discovered snapping shrimp inhabiting the Oregon coast for the very first time. They now suspect the crackling of the shrimp’s claws may serve as a dinner bell for eastern Pacific gray whales residing in those waters.

In this episode, ocean acoustics specialist Joe Haxel describes the myriad of animals that contribute to Earth’s underwater soundscape, including fish that growl and crabs that scratch their backs. Joe discusses how he and his colleagues identified snapping shrimp by their characteristic racket and what the presence of snapping shrimp means for marine life along the Oregon coast.

This episode was produced by Lauren Lipuma and mixed by Kayla Surrey.

Episode Transcript

Shane Hanlon: All right. I wanna talk about noises. I can even hear it now. Noises that really bother you all. What are some things you can’t stand?

Lauren Lipuma: Nanci’s voice. Just kidding.

Nanci Bompey: I’m not offended. I’m not offended. That’s pretty much been my whole life so it is what it is.

Lauren Lipuma: It’s just … Sometimes in the morning times-

Nanci Bompey: It’s loud.

Lauren Lipuma: You’re very loud. It surprises me. It kind of shocks me.

Shane Hanlon: Yeah, one things folks probably obviously don’t know, but when Nanci comes into the office at 8:30 in the morning, she’s one of the most pleasant people at that time, but also one of the loudest. Just say to everyone, “Hello everyone.” For me, since we’re gonna stay on this theme, as the person who always has the headphones on when we’re receding and making sure all the sound and everything is good, there’s a lot of mouth noise you can call it.

Lauren Lipuma: Mouth sounds.

Nanci Bompey: Coming from my microphone.

Shane Hanlon: In all fairness, people have told me that my voice isn’t exactly the most pleasing thing. I have a voice that … let’s call it for podcasting and public radio.

Nanci Bompey: Yeah, that’s what I’ve heard so that should be pleasing.

Lauren Lipuma: There’s nothing wrong with your voice.

Nanci Bompey: Yeah, we’ll see. I wasn’t searching for compliments, but I will certainly take them.

Shane Hanlon: Welcome to the American Geophysical Union’s podcast about the scientists and the methods behind the science. These are the stories you won’t read in a manuscript or hear in a lecture. I’m Shane Hanlon-

Nanci Bompey: And I’m Nanci Bompey.

Shane Hanlon: And this is Third Pod from the Sun.

Shane Hanlon: Okay. We’re not here to talk about Nanci’s voice.

Nanci Bompey: No.

Shane Hanlon: Maybe not. No, but we are here to talk about sound. I wanted to bring in Lauren Lipuma. Hi Lauren.

Lauren Lipuma: Hi guys.

Shane Hanlon: Who has a really fascinating story for us. What do you got?

Lauren Lipuma: Yeah, so we’re gonna talk about sounds in the ocean today. Last year, I met and interviewed a researcher who said studies the ocean soundscape.

Shane Hanlon: Oh, that sounds lovely.

Nanci Bompey: What is the ocean soundscape?

Lauren Lipuma: Well, actually, he will explain it to you, but it’s pretty much all the ambient sounds that you hear in the ocean.

Shane Hanlon: I’m excited.

Nanci Bompey: I wonder if it sounds like my voice.

Shane Hanlon: I’m sure it does not.

Joe Haxel: My name is Joe Haxel. I’m an Assistant Professor at Oregon State University, affiliated with the NOAA Pacific Marine Environmental Laboratory Acoustic Program. I’m based out of Newport, Oregon at the Hatfield Marine Science Center.

Joe Haxel: My specialization is in ocean acoustics. I study sound underwater. Everything from looking at … I use it as a tool, essentially, to look at geophysical processes, look at some ecology in different habitats, as well as impacts from anthropogenic influences on sounds in the ocean.

Lauren Lipuma: What does studying the sound in the ocean tell us?

Joe Haxel: Ocean acoustics is great. The analogy that I like to use is that we use optics in light as creatures on earth to navigate on land. We see the furthest with our eyes. We navigate, and find our food, and all the things we do, we primarily use our eyes. We do hear as well, but we can see a lot further than we can hear. The ocean, due to the physical properties of the water, light scatters really quickly, right, but sound doesn’t. Sound actually travels really far so that’s why most animals are acoustically oriented. They find their food and mates. They travel by sound. Also, as humans, we’ve clued into that too. The Navy has been using it for a long time, acoustics, to do a lot of different naval operations, but even in the commercial sense, we use that.

Joe Haxel: More recently, the technology is becoming more commercially available to where soundscape analysis is really starting to pick up-

Lauren Lipuma: What do you mean by that?

Joe Haxel: A soundscape is essentially like the background song. If you were to close your eyes and just sit and listen, and what the ambient conditions are around there. There’s contributions for all different kinds of sources. And particularly in the ocean, we have natural sound from wind and waves at the surface, and earthquakes, ice processes in the poles. There’s anthropogenic sources like vessel traffic, fishing, activities, energy exploration. People looking for oil deposits. Drilling and pile driving. There’s biological contributions from fish and mammals that are using that, like we discussed, to communicate and orient themselves.

Nanci Bompey: How do they record these underwater sounds?

Lauren Lipuma: Well, they actually just use an underwater microphone.

Nanci Bompey: That makes sense.

Lauren Lipuma: Yeah, it’s called a hydrophone. It’s basically a waterproof microphone and it’s attached to a buoy so they can find it on the surface. They can leave it out there for a long time to record things over time or they can just get a snapshot of what they’re hearing.

Nanci Bompey: I bet when they leave it out there, they hear all sorts of interesting things.

Shane Hanlon: Oh my gosh, I cannot not stop thinking Little Mermaid. It’s like under the sea.

Nanci Bompey: Under the sea.

Lauren Lipuma: Under the sea.

Nanci Bompey: Look at this stuff, isn’t it neat.

Lauren Lipuma: I still know every lyric to that song.

Nanci Bompey: I think I do too. Wow. We’ll have to have a lyric … Like a singalong.

Lauren Lipuma: A singalong.

Nanci Bompey: Oh, a singalong one day.

Shane Hanlon: Oh goodness. Listeners, stay tuned for that one. But in the meantime, weird sounds.

Lauren Lipuma: What’s the weirdest sound you’ve ever recorded?

Joe Haxel: Oh weird sounds. I would say the whales kind of make the weird stuff for me. Actually, fish. Fish make some really funky sounds too.

Lauren Lipuma: Like what?

Joe Haxel: You think these little fish. There’s a fish called the Midshipman. It does this growl.

Lauren Lipuma: That’s so weird.

Joe Haxel: It’s found in the Gulf of Mexico pretty extensively, but they can chorus and get really loud. They growl. It’s this really … It’s not a very big fish, but it’s really low frequency, and strong, and loud. It’s pretty impressive.

Lauren Lipuma: Oh, cool.

Joe Haxel: The other thing is the blue whales, right. The blue whale … We were fortunate. This is a cool story. Typically, blue whales vocalize … Their fundamental frequency that they put out is really low. It’s actually below what we can easily hear. Oftentimes, when you hear things that people play that are blue whale, they have to speed them up. We were lucky. We had recorders out off of Yaquina Head in Newport. A blue whale came in, probably within a kilometer or two of our recorder and was calling. It gave us this unprecedented, clear, awesome recording of a blue whale that you can hear without speeding up because it has the harmonic pieces in it that normally drop out as it propagates.

Joe Haxel: We have this fantastic recording that we can play for people to listen. If you have the right speaker system, which doesn’t take that big of a subwoofer, but you can shake the lights in the a quite easily with this call.

Lauren Lipuma: Wow, that’s awesome.

Joe Haxel: People hear it and they just … There’s nothing that sounds like that. I can only imagine in my head, being in the ocean and hearing that, the thought must be, “Whoa, what is that?” The Starship Enterprise just came in the area, or something like that. I don’t know.

Lauren Lipuma: That’s awesome.

Joe Haxel: Something else that colleagues of mine have pointed out and I saw it at a totally different experiment on the Oregon Coast, is crabs actually come and rub their shells on your stuff-

Lauren Lipuma: What do you mean?

Joe Haxel: And it makes noise.

Lauren Lipuma: Like on your equipment?

Joe Haxel: Yeah, so dungeness crabs scratch their backs, essentially. They come up and if you have some hard frame or whatever, they will come and scratch. The gear that I had that it did it … It’s not a constant thing so the crabs will come into an area. They like new things because they’re scavengers. Something hits the bottom and they’re like rushing over to see what it is. They would scrap and rub, and scrap, then it would go away after a few days.

Lauren Lipuma: What does that sound like really?

Joe Haxel: Rubbing and scraping sound. It’s just like you’d think. Take a crab shell and rub it on metal, kind of thing.

Lauren Lipuma: That’s awesome. That’s so crazy.

Shane Hanlon: So no Little Mermaid.

Nanci Bompey: Unfortunately, they did not find Ariel.

Lauren Lipuma: No mermaids. No crabs. No King Triton with his trident.

Nanci Bompey: Ah, too bad.

Shane Hanlon: Can’t be-

Lauren Lipuma: No sea witches.

Shane Hanlon: Part of that world.

Lauren Lipuma: No, it’s kind of sad.

Shane Hanlon: I know, but lots of really interesting noises. Snip snap bebop.

Lauren Lipuma: Snip snap bebop?

Shane Hanlon: Okay, cool noises. But what does this mean? What are they doing with it? I’m sure there’s a research component of this.

Lauren Lipuma: Science. Well, Shane, do you remember when we interviewed Leigh about collecting whale poop?

Shane Hanlon: Oh, yes.

Lauren Lipuma: Actually, Joe is a colleague of Leigh, so their project they were working on was looking at how noise in the ocean affects stress hormones in whales. But while they were doing this, they actually found something really surprising about sounds in the ocean.

Joe Haxel: A project that’s really fun that I’ve just gotten involved in in the last couple of years is looking at how ambient noise conditions vary along the Oregon Coast, which is something we don’t know at all. There’s really no data out there for it. The tie to the ecology is I’m collaborating with a Marine Mammal Ecologist who is looking at how those variations in noise levels could be affecting stress hormone levels in Northeastern Pacific gray whales.

Joe Haxel: This year, we put some gear out that … We wanted to capture the time signature of the noise levels. We put out these longer-term recorders that could record through all kinds of different weather conditions, as well as vessel traffic conditions and really get the time signature of what the noise-

Lauren Lipuma: So how it changes over time?

Joe Haxel: Exactly.

Lauren Lipuma: What did you guys find when you started listening to the recording.

Joe Haxel: We found something that was really surprising. We were … The drifting hydrophone as it was going over some areas that we were expecting to be very quiet because they were not around any kind of vessel activity, we found in just looking at the noise levels that they were really loud. We went and used a tool called a Spectrogram, which is basically breaking down the acoustic time series or the waveform that comes into the sensor. We were able to look at that. We started to see, wow, there’s these really sharp spikes that we have never seen really before and nothing we were expecting.

Joe Haxel: Started talking to some of our colleagues and looking in literature, and it looked a lot like snapping shrimp, the sound from snapping shrimp. But the trick and why it surprised us so much was that snapping shrimp are really undocumented in this area. They’re typically a tropical or subtropical species, not found in colder waters like we have. We asked around to some of our colleagues in the Department of Fish and Wildlife, and some people that work in the reef and rocky areas, if they had seen shrimp or they knew anything about having snapping or pistol shrimp. Nobody-

Lauren Lipuma: No one had ever seen that before.

Joe Haxel: No one had ever seen them. We sent the recording to them and just, “Well, listen to this.” And they’re, “Well, yeah, that’s snapping shrimp,” most everybody’s saying.

Lauren Lipuma: Tell me a little bit more about snapping shrimp.

Joe Haxel: They’re incredible. They’re really neat little animals. I didn’t know a whole lot about them before and have dove into it. When they snap their claws, it’s not actually the claws hitting each other that’s making this snap, they’re actually producing a high-velocity jet that creates a cavitation bubble. For an instant, that cavitation bubble shoots out from their claws and then collapses violently and that collapse of the bubble is what makes the snapping sound.

Joe Haxel: Think of a ship with a propeller going around on the bottom. It’s going faster and it’s making bubbles; that’s part of what we hear when we’re listening to ships and things like that. It’s just a bubble of air. They collapse and that’s what makes a crapping and popping or the hissing sound the shrimp. Within that bubble, that cavitation bubble, there’s a flash of light that happens. They were actually able to record, some researchers that used high speed cameras back in the 2000, 2001. With the high-speed camera technology, they were able to record. They stimulated the shrimp to snap and then got this image of the bubble coming out, collapsing. There was a flash of light that occurred in that bubble. Their estimate is that the temperature in there, due to that flash of light, was something like 5,000 Kelvin.

Lauren Lipuma: Oh my God.

Joe Haxel: Yeah, ridiculously hot right? And the sound that comes from those is some of the loudest, instantaneous sounds in the ocean.

Lauren Lipuma: How loud are we talking?

Joe Haxel: It’s like the sound … potentially like a gunshot.

Lauren Lipuma: From one shrimp?

Joe Haxel: One shrimp. It’s such a short signal though, it’s on the order of half a millisecond that it’s not long lived, right. It’s a really quick snap. If it was longer duration, it would be a much bigger problem. Plus, a lot of that energy dissipates pretty quickly. It’s a very near field affect. Behavioral Ecologists are looking at it and thinking they use that as a way to stun their prey, but also as a way to ward off other shrimp. I think that reading about them, they’re very territorial. You can’t put two snapping shrimp in a tank together and have them hang out.

Lauren Lipuma: Oh, really.

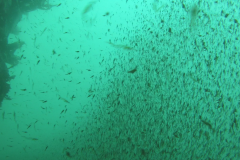

Joe Haxel: They don’t get along very well with each other. But you get hundreds and thousands of these shrimp along a coastal habitat, and it is incredibly loud. Oftentimes, the individual snaps aren’t … You can’t pick those out, it just sounds like a hiss because there’s so many of them and they’re from far away. When you’re right up close to them, that’s how we knew we were right on them too is that our recordings were so clear and we could hear individual snaps and actually count them.

Lauren Lipuma: When you’re that close to them, what does it all sound like?

Joe Haxel: It’s like Rice Krispies cereal, but boosted. Yeah, it’s impressive. It’s really pretty neat.

Lauren Lipuma: Do you know about how big they are?

Joe Haxel: They’re not very big. They’re maybe a couple of inches long, maybe two, two and a half inches long. Pretty small little guy for a big, big sound.

Nanci Bompey: So they found these, or they heard, these snapping shrimp.

Lauren Lipuma: Yeah, shrimp. Remember when Adam was talking about going down an Alvin and they had the shrimp button on the boat and you could be like-

Shane Hanlon: Shrimp, shrimp, shrimp, shrimp, shrimp.

Lauren Lipuma: Again.

Shane Hanlon: You’re welcome.

Lauren Lipuma: Again. Again with that. Oh, guys.

Shane Hanlon: Of course. Remember when I saw this episode, I was like, “Oh, I get to sing. This is fun.”

Lauren Lipuma: Shane’s Rihanna cover.

Nanci Bompey: I do recall that. But aside from that, these snapping shrimp … But they found something else out that’s pretty cool. I guess it’s related to the whales, right?

Lauren Lipuma: Yeah, they found that the whales are actually using the sound of the snapping shrimp kind of like a dinner bell. It’s like a sound cue that pulls them to places, these rocky reef areas where there’s a lot of food for them to eat. One thing that whales eat are these creatures called mysids, which are small crustaceans. They’re pretty much very similar to shrimp, but they’re not exactly shrimp.

Nanci Bompey: Mysids.

Shane Hanlon: Or eusids.

Nanci Bompey: Oh, was that supposed to be funny?

Shane Hanlon: No, it’s not at all.

Joe Haxel: We started looking closer into the data and they were characteristically found around the rocky reef areas, and more particular in areas that had kelp. That’s where we were also seeing the whales very frequently, feeding in particular with foraging activity. We started putting down … Lee’s group has GoPro camera drop that we can use. We started putting down GoPro camera drops in these areas and getting images of what the whales were eating. They were big clouds of mysids in the water in these areas. That kind of led us to the idea that we needed to explore potentially that these snapping shrimp were acting as a potential cue, or acoustic signal, for the whales that, “Hey, there’s an area over here that may have the type of food that I’m interested in.”

Joe Haxel: The whales are acoustically oriented like I mentioned. I think they are feeding around the clock, 24 hours a day, and nighttime, and every time. They’re using some type of cue to be able to find this food. They’re really good at figuring out where food is. The prey is really patchy. It’s not like they go out and there’s just big cloud layers of mysids all over the place. They’re typically found in these little pockety areas, and I think around kelp in particular because it helps them hide in the coastal zone.

Joe Haxel: They’re finding these guys somehow. That probably isn’t the only way they’re doing it, but the acoustics is definitely a strong sensory mechanism for them. They use sound to do a lot of different things. This kind of pushed us in this way that there’s something to this signal that’s so loud in this area and is associated with a particular habitat where we’re finding the whales a lot.

Lauren Lipuma: So you were totally surprised to see snapping shrimp there. They have never been seen off the Oregon Coast. Is this the first time they’ve been seen this far north?

Joe Haxel: Yes.

Lauren Lipuma: Wow.

Joe Haxel: That was interesting. That is another interesting part of this is that that opens up a whole nother suite of questions. Have they always been here? In which I would doubt because I think somebody … There aren’t a lot of recordings, obviously, acoustic recordings, but the Navy has been working with snapping shrimp for quite awhile. That’s where a lot of the history of the research was because they were hearing the snap and hiss through their submarines, sonar text for saying there’s something out there that’s messing up everything we’re looking at. The navy put in a significant amount of money to research snapping shrimp. That’s where a lot of literature comes from already.

Joe Haxel: The next step we need to do was trap some of these guys, figure out what species we’re dealing with. I think that will give us clues as to what we’re seeing. Are they snapping shrimp that have moved north, as a lot of species are being seen to do? The pelagic species and whatnot are being found a lot higher latitudes. Is that part of it or are they a species from the western Pacific that may have come over with rain debris or something? We don’t know so that’s why we gotta catch them. Figure it out, that’s the next step.

Lauren Lipuma: Yeah, gotta catch them.

Joe Haxel: Yeah. Sound, there’s all kind of stuff that can be looked at with sound once you have the basics and you have the tools, and then you have the understanding of how sound works in the ocean, you can apply it to a ton of different things.

Nanci Bompey: I wonder if they could use the sound of my voice to do science experiments?

Shane Hanlon: What’s the opposite of a dinner bell?

Nanci Bompey: Good one!

Lauren Lipuma: Your voice just makes everyone run away.

Shane Hanlon: I had to redeem myself from earlier.

Nanci Bompey: That’s a good one. That’s a good one.

Shane Hanlon: All right. Well, that’s all folks, from Third Pod from the Sun.

Nanci Bompey: Thanks so much to Lauren for bringing us this story, and of course, to Joe for sharing his work with us.

Shane Hanlon: This podcast is also produced with help from Josh Speiser, Olivia Ambrogio, Katie Broendel, and Liza Lester. Thanks to Kayla Surrey for producing this episode.

Nanci Bompey: We’d love to hear your thoughts on our podcast. Please rate and review us on iTunes. Listen to us wherever you get your podcasts, and of course, always at thirdpodfromthesun.com. And-

Shane Hanlon: And-

Nanci Bompey: One more note, we’re actually collecting stories about funny field work stories, failures, when things just didn’t go quite as they had planned. If you have a funny story, email us at [email protected]. Tweet at us, call us. Hunt us down in the street, whatever, and you could find yourself on this podcast.

Shane Hanlon: Thanks all. We’ll see you next time.