E19 – Eavesdropping on the Ocean

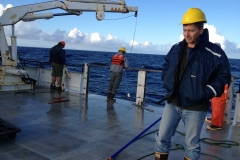

Deploying a hydrophone mooring in Antarctica aboard the Korean ship R/V Araon. Credit: Lauren Roche.

To those of us on land, the world underneath the oceans seems quiet and serene. But scientists who study ocean acoustics will tell you it is anything but tranquil underwater. Our oceans are home to a cacophony of sounds – from the songs of marine mammals to the cracking of icebergs to the rumbling of earthquakes to the roar of ships.

In this episode, Bob Dziak, head of NOAA’s acoustics program, describes the sounds scientists study with their underwater microphones, including the noises they’ve heard at the deepest part of the ocean in the Mariana Trench and a mysterious “bloop, and how they use that information to understand natural processes and the impact from human activities.

This episode was produced by Nanci Bompey and mixed by Kayla Surrey.

Transcript

Shane Hanlon: Hello Nanci.

Nanci Bompey: Hey Shane. So you just got, you just returned from vacation not too long ago.

Shane Hanlon: I did. I did, yeah, a couple of weeks ago.

Nanci Bompey: So how was it? Where’d you go? What’d you do?

Shane Hanlon: It was good. So I went to Washington State, did the national parks there, so Olympic, North Cascades, Rainier, St Helen’s, not a national park but, but yeah it was neat. Lots of hiking. But something really cool we found, my partner found, I can’t take credit for this, what’s called the quietest place on earth.

Nanci Bompey: What?

Shane Hanlon: I know, I know. What it is, so it’s not actually the quietest place on earth but, an artist went into a point in Olympic and basically put a rock, a little red stone off-trail, back in the woods somewhere. And the whole idea is that you’re supposed to reflect on just, just stand there, listen to nature and don’t make a fricking noise. But like, it’s…

Nanci Bompey: But that rock marks the spot or whatever?

Shane Hanlon: The rock marks the spot.

Nanci Bompey: So people go, look it up or whatever.

Shane Hanlon: Yeah, so it’s really funny cause it’s like, the park knows about it, all of that. There is kind of a trail leading to it, but you literally have to, because there’s no cell service or anything in there. It’s in one of the rain forests and you have to look at this guide and they’re, okay, so you’re going to pass this tree that’s destroyed and then walk through another tree that has a hole in it and then go over this log in this swamp, hang a left. It’s literally like this type of stuff.

Nanci Bompey: Oh that’s fun. That’s kind of fun. So was it, I mean obviously you hear birds, you hear sounds and things like that.

Shane Hanlon: Yeah, I mean no, it was really cool. It’s because it is, it’s in the center or pretty close to the center of the park. So you just listen and just, quiet. And that’s just something we don’t have in Arlington, Virginia.

Nanci Bompey: This is true.

Shane Hanlon: Welcome to the American Geophysical Union’s podcast about the scientists and the methods behind the science. These are the stories you won’t read in the manuscript or hear in a lecture. I’m Shane Hanlon…

Nanci Bompey: And I’m Nanci Bompey.

Shane Hanlon: And this is Third Pod From The Sun.

Okay, well the reason why we’re talking about the quietest place on earth, is today our podcast is about sound.

Nanci Bompey: Yeah, underwater sound. So I interviewed Bob Dziak, who’s at NOAA in Newport, Oregon. And he does underwater acoustics, so they listen to the sounds at the bottom of the ocean.

Shane Hanlon: Very cool. So let’s hear it.

Bob Dziak: My name is Bob Dziak. I lead the Acoustics Program in NOAA and I live in Newport, Oregon, and we have a research lab down there.

Nanci Bompey: Awesome. So tell us a little bit about what that means to lead the acoustics program.

Bob Dziak: Oh, well, we do acoustics, underwater acoustics. So we study sound in the ocean. We do a variety of different topics that we look at, to look into with acoustics. We use it as a tool to study sea floor, earthquakes and volcanoes. We do ambient noise research, looking at the impacts of man-made and natural noise on marine ecosystems. And we also do bioacoustics looking at, for example, big baleen whales, marine mammals, looking at their distributions throughout the oceans.

Nanci Bompey: And so what are you using that acoustic stuff for? I mean, other than, I mean, just getting this basis of what’s down there, what it sounds like?

Bob Dziak: Yeah, well, that’s right. So you know, we’ve come to realize is that there aren’t really any good baseline measurements of sound in the ocean and it’s been known, for the last decade or so, that sound has been increasing in the ocean since the 1960s, and also because of increasing ship traffic globally, commercial shipping from container ships to all kinds of things. So man-made noise in the ocean is increasing. It probably has some kind of impact, but we don’t really know exactly and we don’t really have good, like I said, good measurements of what is normal, what is the sound level now. So we’re making sound level measurements now so that we can know how things are changing in the future. And if things, if there’s been impacts or changes, then we’ll be able to assess that a little better.

You know, there’s a big area of research on just how noise impacts marine animals, what was the response to that? And so that’s still kind of a, you know, still coming along. It’s not well understood, but it’s getting there. And another part of it is that in the Arctic, the sea ice is receding and disappearing and so that’s gonna be opening up shipping lanes over the North Pole. And so there’s going to be more shipping going up there. And so that was once a pristine area. Now it’s going to be introduced to more noise. And so our goal is to kind of assess that.

Shane Hanlon: I imagine there’s some really wild sounds that they’re getting. What are you, so if you could pick marine animal, what sound do you think- what’s the coolest sound you think of marine animal makes? What animal do you think makes the coolest sound?

Nanci Bompey: I would say whales, right? I mean, don’t we know they make some cool sounds?

Shane Hanlon: Yeah, I mean I definitely- I know, I just wonder if there’s probably things so deep, right? That-

Nanci Bompey: You don’t even know.

Shane Hanlon: You have no idea. They’re not seeing anything. They have to be communicating via sound.

Nanci Bompey: Yeah. I remember we did that episode a couple weeks ago about the – or months ago – about the snapping shrimp. Like those might … I wouldn’t have known about that. It sounds like popcorn-ish.

Shane Hanlon: Yeah. Imagine being underwater and just hearing that, it’d be like what is going on?

Nanci Bompey: That’d be so cool. That’d be so cool.

What is your favorite recording that you’ve done? Do you have one? I mean, that’s an odd question, I guess maybe.

Bob Dziak: Oh yeah, I have so many. Oh, I like- I think they’re really, there’s a really cool one of iceberg grounding. I think is really fun.

The biggest iceberg off the Antarctic peninsula. It broke free, and it’s like 60 miles long. And so it was just floating in the deep ocean and it kind of got blown back into the continental shelf, and it runs aground and it starts resonating kind of like if you hit a tuning fork and just resonating. So that’s what this thing does. It just sounds big moaning, resonating sound. It’s like the equivalent energy of a magnitude six earthquake. So it’s a big amount of energy. But it’s just this big tone.

I like the ice noise sounds a lot. The marine mammals are really cool. I mean, the big baleen whales records we have with us are really cool, the blue whales.

Nanci Bompey: What do those sound like?

Bob Dziak: Oh that’s a really low frequency.

So in my lab, I’ve kind of tried to explore how to better represent sound in the ocean, visually and for public outreach events. So I’ve invested in a big subwoofer, a big speaker. So you play these big low frequency sounds really loud. And so that’s the blue whale, it’s lowest tone is about 17 hertz. And it has overtones that spaced up, equal spacing above that. So 34 and upward. But humans can only hear down to 20. So you can’t really hear it. So if you crank it really loud with the big subwoofer speaker and it starts moving, you can kind of feel it. And so that’s your experience, you get the big, the blue- if you imagine you’re right next to a blue whale, it kind of makes you a little woozy because the air’s moving back and forth. So it kind of, it makes you a little dizzy and a little bit of Vertigo. So that’s, that’s how I, that’s why I try to represent the sound and that’s what I think is a cool one.

Nanci Bompey: No, that’s very cool. That’s very cool. So you know, I guess, from doing this for so long, you can pick out what it is? Or sometimes are you like, what is that?

Bob Dziak: Well, sometimes literally I don’t know what that is. I’m just saying I don’t have any idea. Oh I kinda, well, you know, every signal, every sound has its certain frequency characteristics. And so from that, after time you begin to understand what, what’s making it. If it’s an earthquake, it’s pretty diagnostic. It’s low frequency under 10 hertz, long duration. A marine mammal call, like I said, they’re harmonic tonal sounds. Pretty easy to tell. Maybe not easy to tell what species, but you can tell, that’s probably an animal.

Air guns real simple- a burst, explosion. Ship noise is this kind of higher frequency, 100 hertz sound that goes on for several minutes as the ship goes overhead and you can, you see that Doppler shift, the change in frequencies is going overhead and it goes away. So you know, after all that time, you kind of see all these things, oh yeah, that’s, this is that.

Nanci Bompey: But have you ever been totally confounded or surprised by anything that you’ve picked up? And been like, oh my God.

Bob Dziak: No, not too much. I mean, most things I would say, well that’s, I don’t know what that is, but it’s probably seismic or I don’t know what that is, but it’s probably bio, you know, biology or bioacoustics. Yeah. I don’t know if you’ve, I hesitate to bring this up, but there’s this thing called the bloop sound, which has been something that a bloop. Yeah, bloop. Yeah that got, kind of got some traction in the media in the late nineties and somebody in the press had said they thought it was a giant squid. It was on our website just as an unknown sound. And the thing has just gone on and on and on. It’s on conspiracy theories and all these things. I think is just an ice noise. I think it’s something from Antarctica that made noise, like an iceberg broke apart, but, and I’ve published that and, but it’s still kind of, it’s out there. If you Google bloop, you will find all this stuff about it.

Shane Hanlon: Okay. I need to know. I need to know what the bloop is.

Nanci Bompey: Well, let’s Google it.

Shane Hanlon: Are we going to Google it?

Nanci Bompey: Okay. I Googled it.

Shane Hanlon: All right. What do we got?

Nanci Bompey: I googled it. Here’s the bloop.

Shane Hanlon: Oh, what is that?

Nanci Bompey: That’s a bloop.

Shane Hanlon: Oh man. It’s like, it’s like the… It’s like the Loch Ness monster bloop.

Nanci Bompey: I love how people, I think there was like a whole, you know, there was a lot of, there was a lot of conspiracy around this bloop, but I guess they- I’m reading here, they actually, it was an iceberg cracking, they think. So that’s what they-

Shane Hanlon: Oh, that’s like a, that’s like with a whimper and not a roar type deal.

Nanci Bompey: Yeah. Anyway, very interesting. I love the bloop.

Shane Hanlon: I like the bloop.

Nanci Bompey: So I know you guys went out to, you’ve done really deep stuff. That’s what we’ve kind of … Yeah. So where, where is the- I mean, what was the deepest stuff that you’ve done or what’s the stuff that you’ve been doing recently in the deep?

Bob Dziak: We worked in Challenger Deep, which is in the Mariana Trench, near Guam and the Mariana Islands. It’s the deepest spot in the global oceans, and I discovered through my research that no one had ever made a sound recording down there. Way back, there was one short one that was made during the epic dive with the Trieste, which is a bathyscaphe submarine, that was in the 1960s, Jean Picard did. But it wasn’t a modern digital record. So we built a special hydrophone mooring and put in a special pressure case, that could withstand those huge amounts of pressures, and deployed it in the Challenger Deep, and it worked successfully.

Nanci Bompey: And how deep is the Challenger Deep?

Bob Dziak: It’s 11 kilometers or 36,000 feet, or about seven miles.

Nanci Bompey: Seven miles? Oh Wow.

Bob Dziak: So it’s deep, deep, deep.

Nanci Bompey: So what are these hydrophones that you have to design? You said you have to design, kind of a special- you have to design a special hydrophone or you can use just a regular? Or what are these- and do you build the hydrophones yourself or do you buy them or?

Bob Dziak: We do. That was our, our big- we’ve been a program for about 20 years, and back then we had to develop these hydrophones because nothing existed commercially. And then our very talented engineer, named Haru Matsumoto, built a portable, we call it autonomous, but a portable hydrophone that essentially is just an underwater microphone. It’s a ceramic element so it can withstand all that crushing water pressure. But it has to be in a case, a pressure case. And so they’re- we make them out of titanium typically because it withstands all that intense squeezing and that’s it.

So it just, the little a microphone sticks out of the case and you throw it over the side of the ship, and it sinks down. It takes a little finagling because you have to have it sink at a slow enough speed in order- because if it goes too quickly it’ll crack it. So that was the, that was the skill of our lab in designing a mooring that was buoyantly, could control its buoyancy well enough that it could just slink, sink at about 50 centimeters a second.

Nanci Bompey: So it goes down by its own weight then? I mean, you’re not lowering it?

Bob Dziak: Right, exactly. We don’t put it on a wire, we just kick it over to the side and it free falls and then we try to- and the, actually the deepest part of Challenger Deep is this little hole, down there. So it’s like one of those little games, with a little ball you’re trying to get in the hole. And you kind of have to judge the currents and you kind of pull the ship back up and then you kick it over the side.

Nanci Bompey: So for the Challenger Deep, how long did it take you to get it down there?

Bob Dziak: Oh, it takes about six hours.

Nanci Bompey: Oh wow. Okay.

Bob Dziak: Yeah takes a long time.

Nanci Bompey: Is it nerve-wracking watching it going down there or are you pretty confident that it’s going to be okay?

Bob Dziak: Well, no, we’re not confident at all that it’s going to work. You know, we can range to it with the echo sounder, a transducer. So we talk to it. And as you can see it kind of go, we range until we see it’s going down and it’s going down. It’s going down. So we feel confident that it’s sinking in a right rate and we know where it kind of is. But all kinds of things go wrong all the time. It could leak. It could be- this is all kinds of things. It could get stuck in the mud. There’s lots of little things that crop up with moorings that makes it hard to get back. I guess, not too surprisingly, it was a very noisy record in that there was lots of ship noise, lots of wind and wave noise. Storms typically dominate. Wind and wave typically dominate a sound record in the ocean. And that’s just, and that goes all the way down to the bottom of Challenger Deep. I mean, just- the surface waves when a big storm, you can hear that all the way down there.

Nanci Bompey: Oh Wow. You can hear that, all that. So it’s not quiet down at the bottom of the ocean.

Bob Dziak: It’s not really that quiet. No, I mean it is quiet. Don’t get me wrong. The quiet periods are really quiet but it’s still noisy at times. And we could hear surface animals, we could hear odontocetes, toothed whales and baleen whales.

I’m not really sure what species, but we can hear them on the records and play that back. And Challenger Deep, we heard all kinds of things. Lots of earthquakes, which you sort of expected because Mariana trench is a big active seismic zone. There’s lots of earthquakes. And we heard…

Nanci Bompey: What does an earthquake sound like, if that, I mean…

Bob Dziak: Oh like thunder.

Nanci Bompey: Like thunder?

Bob Dziak: Yeah, that’d be the best analogy. You play back… Yeah so it’s the- earthquake is…Like animals when they make sound, like humans, it’s kind of a focused harmonic sound, tone. Earthquakes are just kind of noise, kind of low frequency noise. It’s like a drum roll or something. And then energy gets out in the water and it propagates along the trench. Mariana trench is a big canyon, in a sense, an underwater canyon, so it really channelizes a lot of the acoustic energy too. So if it gets trapped in there, it kind of bounces back and forth and goes laterally and probably gets along.

So we were seeing all kinds of seismic energy that way. Lots of ships, a lot of ship noise because Guam is a major shipping hub, plus there’s a very large navy base there, so all kinds of ships, all kinds of … And as I said, several marine mammals. Interesting ones were hearing the whistles of the dolphins, I think they were dolphins or some kind of odontocete. Some kind of toothed animal that, so they kind of, they have clicks and whistles and you can hear just this faint little whistling all the way from the surface. So that was cool.

Air guns unfortunately. Active sonar. I say unfortunately because it’s sort of noisy. It’s an air gun that is used for oil exploration and things or whatever, for any kind of imaging. This was a big explosion. And then active sonar which was really impressive, that we heard in the canyon. I mean, I assume it was military, probably. It was a very loud ping. They’re kind of, they’re looking for something. And so that went on for a few hours.

The only challenge was in the deployment. We were on a coastguard ship, it’s a buoy tender, it’s a big ship. But we were on the checkout cruise for the ship when they had a bunch of new recruits, and they agreed to take us out there and the captain wanted to test them a little bit. So it just so happened that day we went, there was a big typhoon going right over the spot we wanted to go to. And so she said, we don’t care, we’re going. We literally went right into a typhoon and then just turned right around and came back. It was the worst weather I’ve ever been in. It was…

Nanci Bompey: Oh wow, it was the worst weather, and you’ve been on ships for how-

Bob Dziak: A lot.

Nanci Bompey: Yeah.

Bob Dziak: The North Pacific. And this is around the equator, it’s supposed to be nicer, but it was horrible. It was 30 foot seas and sixty mile an hour winds and everybody was sick.

Nanci Bompey: Oh my god. Yeah. So what is that? Well, just a little bit about that. I mean, you’ve been on ships for many, obviously, how many years? I mean, you’ve been doing this for a long time, so what is it like, I mean, being in that kind of weather, I mean is it like, what is it like to be on a ship when you’re-

Bob Dziak: Oh it’s miserable, absolutely miserable. You can’t, can’t focus, can’t nothing. You don’t, you’re not hungry. Yeah. It’s really hard to work, and that’s being at sea, it’s a difficult work environment for that reason because it’s kind of unsettling and even when you’re used to it after years, I still kind of, you’re out of your element. So you have to have everything really well prepared and well thought out ahead of time because you figure that when time comes it’s just so unsettling and you know in the moment that you can make a lot of mistakes and it can be dangerous. So you have to be very careful.

Nanci Bompey: Yeah. Being seasick is disgusting. I think I talked about this in a previous episode though. I was on the boat. It was, I didn’t get seasick because I wore the patch but it was rough. But I get motion sick just on the metro.

Shane Hanlon: On the metro?

Nanci Bompey: Yeah. I’ve to sit facing forward and if it’s longer than like five stops, I can’t read. I can’t look at my phone.

Shane Hanlon: Does it matter if it’s above ground or below ground?

Nanci Bompey: Yeah, there’s- When you’re below ground, because you can’t look out. Oh yeah. I am not. And then here in D.C., for people who don’t know, the metro, like they drive the trains. It’s not some automatic, automated smooth ride. So nauseating.

Shane Hanlon: I’ve never really gotten sick on the metro. I just don’t like, I just get sad because it’s just dark, underground.

Nanci Bompey: I was always that kid who had to sit up front in the bus or in the car because I was going to throw up.

Shane Hanlon: You bus in though. Are you okay on the bus?

Nanci Bompey: Yeah, weirdly I’m okay on the bus. I don’t know why. Maybe my body- and you could look out the window, I guess maybe, so maybe my body is good on that.

Shane Hanlon: You can look out the window.

Nanci Bompey: But it is miserable when you are feeling so sick like that, and to be on a boat you can’t leave. You know what I mean? You can’t leave and you have to do your work.

Shane Hanlon: I’ll keep this in mind next time I’m in the metro with you and we’re going somewhere.

Nanci Bompey: And what’s the next big project that you guys have coming up or that you’re working on?

Bob Dziak: Oh, well we’re doing a lot of research in Antarctica and we’re going to be putting hydrophones on a bunch of ice shelfs, ice shelves, ice sheets, off there as they’re beginning to crack apart because of water warming and climate changing.

Nanci Bompey: And that stuff on the ice shelves, you actually put it on the ice? Or you’re like a little bit under or you’re off to the side, off the boat. I don’t know. How does that work?

Bob Dziak: Yeah, right, well the ice shelves are usually- the one we’ve been studying in the Ross Sea, David Glacier. It’s the fastest moving glacier in Antarctica and it moves so quickly that it just kind of sends this ice shelf out in the water. So it sort of floats and goes out a mile, two miles. And as we put the hydrophone moorings, this is a mooring, the shelf side, like the mooring is sitting right here. So it can hear all the creaking and groaning and cracking of the ice shelf. And what I’m having a poster on today is this, this is called the Nansen ice shelf. It was part of the system. It started fracturing in 1987 but just broke free in 2016. Just recently. So we kind of caught all those sounds as it broke free. So we’re learning, kind of analyzing what, what were the conditions were that led to it breaking apart.

Nanci Bompey: And how did the sounds help you figure out kind of the, about the conditions? How do you, what do you correlate the sound to what’s going on? Kind of?

Bob Dziak: We do.

Nanci Bompey: Yeah.

Bob Dziak: Yeah. Well it’s called, we’d call, I’d call them ice quakes. So it’s basically an earthquake, but ice. And so it makes these really impulsive little sounds and you know, when a big shelf begins to crack then it’s, 200 meters thick and it’s a couple miles long. Yeah, it makes a lot of ice quakes and it kind of breaks free like a fault.

And so, just seeing through time, you can see where, I think where we saw the shelf break free, but it stayed put it was pinned or something. It was still grounded because it didn’t float away until about two months later. I think it was free floating or pinned somehow, just on it’s, like a little bit of a keel. And then it popped it up. Pop it up. So what’s fun about working with land geologists too, is that, so they had all kinds of GPS sensors on this thing and seismometers so they knew what it was doing and how fast it was moving or wasn’t moving. So the GPS sensor said it was stationary, so that was another part of the puzzle. But I say it broke free but it looked like it didn’t move and so we got- so it makes a story.

Nanci Bompey: Yeah. That’s so cool. Yeah. Because they can’t, they’re not looking, they’re looking at the top. They can’t see the underneath and through the sound you can actually understand what’s going on.

Bob Dziak: Yeah, right. That’s my role is to kind of add to what we can picture from the water perspective.

Shane Hanlon: Oh, so I guess the bottom of the ocean actually isn’t all that quiet.

Nanci Bompey: No, it’s like the ocean’s really loud. And I guess I was just thinking, you went to the place, like you said, it was an artist thing. Like oh, hear, come hear the- I wonder where like the actual quiet place, you think it’s like Antarctica, on the ice somewhere. I don’t know, the actual quietest place on earth.

Shane Hanlon: Well, what about like- what about the place… SETI? Aren’t those the quietest places? Like where they’re listening?

Nanci Bompey: Oh.

Shane Hanlon: Because aren’t those actually like no device, no sound…

Nanci Bompey: Right. They have to be out in the middle of nowhere. Oh, in the desert or whatever. Right. Is that where they are? I don’t even know where they are.

Shane Hanlon: Yeah, I think so. We should look into this. That’d be fun to talk about.

All right, so that’s all from Third Pod From The Sun. Thanks to you, Nanci, for bringing us this story.

Nanci Bompey: You’re welcome. And of course, thanks to Bob for sharing his work with us.

Shane Hanlon: Ah, the podcast is also produced with help from Josh Speiser, Olivia Ambrosio, Liza Lester, Lauren Lipuma and Katie Broendel. And thanks to Kayla Surrey for producing this episode.

Nanci Bompey: We would love to hear your thoughts on our podcast. Please rate and review us on iTunes, and you can always find new episodes wherever you get your podcasts or at thirdpodfromthesun.com

Shane Hanlon: All right. Thanks all, and we’ll see you next time.