Centennial E9 – The Sun and the Exploding Sea

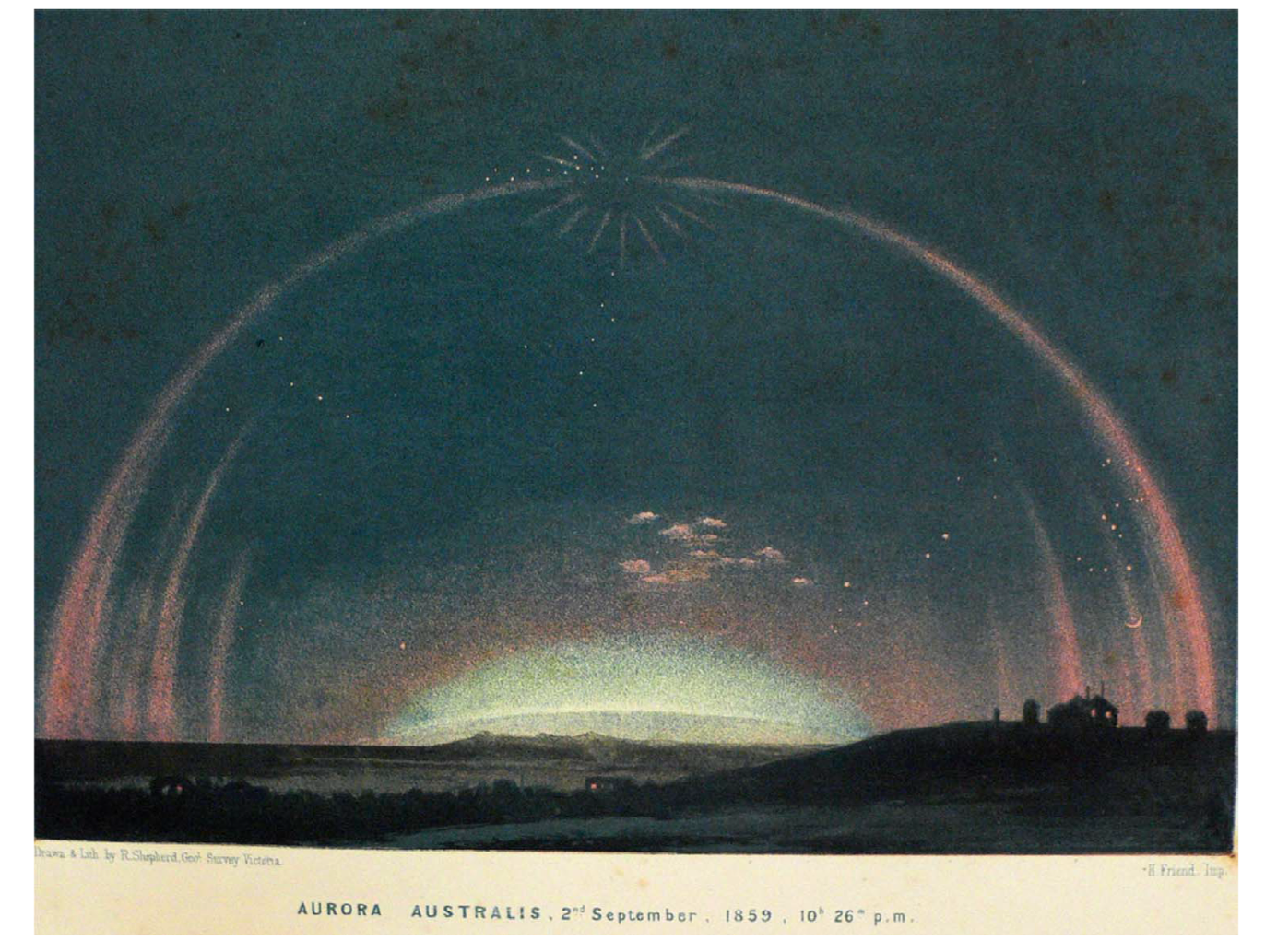

Drawing of an auroral display with a corona at Melbourne Flagstaff Observatory (S37°49′, E145°09′; −47.3° MLAT) at 22:26 on 1859 September 2, reproduced from Neumeyer (1864).

In 1972, in the waning years of the Vietnam War, U.S. military pilots flying south of Haiphong harbor in North Vietnam saw something unexpected. Without explanation, and without warning, over two dozen sea mines suddenly exploded. While the phenomenon was never officially explained, it piqued the interest of space scientist Delores Knipp.

Knipp is a research faculty member at the University of Colorado Boulder Smead Aerospace Engineering Sciences Department and editor in chief for the AGU journal Space Weather. She originally wanted to be a meteorologist but joined the ROTC in a weather position right with the goal of staying for four years to pay off her student loans. Twenty-two years later, she retired after a career with the Air Force studying weather or space weather.

Being a scientist on an Air Force presented some unique opportunities to educate her colleagues, specifically answering questions like, “What is dark?” It might sound silly but it’s a big deal when determining flights schedules. But she really started diving into some of the more mysterious stuff after she retired.

In this Centennial episode of Third Pod from the Sun, Knipp provides a unique perspective about the role of space weather in shaping global policy and conflicts. From a chance phone call from a colleague encouraging her to solve a decades old mystery to pulling out clues from the obituary of an Air Force commander, Knipp unravels some of the biggest space weather mysteries that many of us have never heard of.

This episode was produced by Shane M Hanlon and mixed by Collin Warren.

Transcript

Shane Hanlon: 00:00 Hi Nanci.

Nanci Bompey: 00:01 Hey, Shane.

Shane Hanlon: 00:02 Hi.

Nanci Bompey: 00:02 Hi.

Shane Hanlon: 00:03 So, we’re going to get back to question time. I know you-

Nanci Bompey: 00:06 Oh, I love question time.

Shane Hanlon: 00:06 I know you love question time. If you were to lose power, say, like in a blackout or something, but you could power one thing, not your phone, what would you electricity for, like one thing?

Nanci Bompey: 00:19 Well, this is silly.

Shane Hanlon: 00:21 That’s the point of this exercise.

Nanci Bompey: 00:22 My electric toothbrush. It’s one of those stupid things that you’re like, “I’ll never get an electric toothbrush,” and then you get one, and you’re like, “This is pretty amazing.”

Shane Hanlon: 00:32 What’s so amazing about it?

Nanci Bompey: 00:34 Because, you know what, I used to really brush my teeth very hard. I don’t know, I guess I do everything with gusto.

Shane Hanlon: 00:39 Gusto.

Nanci Bompey: 00:40 And I did it so hard that my gums were really messed up and really receding. And they’re like, “Your teeth are going to fall out.”

Shane Hanlon: 00:51 This is so much better than anything I could anticipated.

Nanci Bompey: 00:55 So they said, “You should get an electric toothbrush because it does the right amount of pressure and whatever. It brushes it correctly, brushes you correctly.”

Shane Hanlon: 01:02 So in the apocalypse, if you have one of those tiny little like solar panels that’ll charge one device, you’re going to charge your electric toothbrush and nothing else. This is a good thing to know.

Nanci Bompey: 01:09 I know. Sad.

Shane Hanlon: 01:12 Welcome to the American Geophysical Union’s podcast about the scientists and the methods behind the science. These are the stories you won’t read in the manuscript or hear in a lecture. I’m Shane Hanlon.

Nanci Bompey: 01:25 And I’m Nanci Bompey.

Shane Hanlon: 01:26 And this is Third Pod From the Sun, centennial edition.

Shane Hanlon: 01:32 All right, so now we know that in a blackout, let’s say, you’re going to take your toothbrush with you, or you’re going to charge your toothbrush.

Nanci Bompey: 01:41 Or like, I couldn’t brush my teeth. I’ll be the first of the zombie apocalypse to go, “I need my toothbrush.”

Shane Hanlon: 01:47 But have you ever been in like a big blackout or lost power for … I mean, we’ve all lost power, but like for extended periods?

Nanci Bompey: 01:54 I guess the last big one was the derecho.

Shane Hanlon: 01:57 Derecho.

Nanci Bompey: 01:58 Whatever that was that happened. I don’t know how many years ago, about maybe six or seven years ago maybe now, or eight years ago.

Shane Hanlon: 02:05 Oh no, I was living here.

Nanci Bompey: 02:05 It was like my first summer in D.C. It was 110 degrees.

Shane Hanlon: 02:08 Oh nice.

Nanci Bompey: 02:09 It was insane.

Shane Hanlon: 02:11 How long did you lose power for?

Nanci Bompey: 02:13 At least three or four days I feel.

Shane Hanlon: 02:15 Oh wow.

Nanci Bompey: 02:15 And it was so hot, so I just took cold showers and laid around. Yeah, it was awful. People were like going to the mall was the only place where you could charge your phone and get air conditioning.

Shane Hanlon: 02:27 Oh wow.

Nanci Bompey: 02:27 It was pretty awful. It was pretty awful.

Shane Hanlon: 02:29 Yeah. Well, so okay, so something like a derecho, like natural hazards, things on Earth can cause blackouts. Did you know that also the sun could potentially cause blackouts?

Nanci Bompey: 02:40 Yes, space weather.

Shane Hanlon: 02:40 I know. Well, we actually have the opportunity to talk to someone who knows all about space weather and what exactly space weather is, I guess.

Delores Knipp: 02:55 My name is Delores Knipp. I’m a research faculty member at University of Colorado, Boulder at Smead Aerospace Engineering Sciences Department. In my somewhat spare time, I’m the editor in chief for Space Weather Journal, which is an AGU publication.

Delores Knipp: 03:13 Space weather is the disturbances in the environment in which our satellites operate, our radio signals, communication signals propagate, and in which some humans, astronauts, work, but space weather has a way of kind of expanding and working its way all the way down to Earth.

Nanci Bompey: 03:34 So, for people in the space weather community, Delores is a very big deal.

Shane Hanlon: 03:38 Yes, very much so. It was really fun to talk to her. She’s dedicated a lot of her more recent work to studying kind of these historic space weather events, which we got to chat with her about. But, I found out, I had no idea, that she actually has a really fascinating background.

Delores Knipp: 03:54 When I graduated college I wanted to be a meteorologist. I had trained for that and done education in that regard, but it was just at the end of the Vietnam War, and there were a lot of experienced meteorologists coming back from Vietnam, so someone with no experience really didn’t have much of a chance to get a job. But, the Air Force had openings sort of at the entry level for weather, and so I joined ROTC and the Air Force. I was going to do this for four years go pay off my student loans, and four years turned into 22. And all during that time, I was involved in either weather or space weather for the Air Force.

Delores Knipp: 04:38 So, I had this sense that there were disturbances that people couldn’t see, that were going on and affecting military equipment and military operations. And I’d gotten that sense when I was a weather briefer at Cheyenne Mountain Complex in Colorado Springs. I ended up pursuing that, trying to understand what was going on beyond the atmosphere.

Shane Hanlon: 05:05 Were you uniformed?

Delores Knipp: 05:06 I was uniformed.

Shane Hanlon: 05:07 That’s very cool.

Delores Knipp: 05:08 It turns out that the weather folks at any given base weather station, which was what it called at the time, were generally viewed as the scientists on base. In many cases, we were pretty far from having any answers, but at least the training that you got in meteorology school gave you a sense of who you might contact or where you might go find an answer. And so, I got asked some really strange questions like, “What is dark?” The reason has to do with we had pilots who needed to get a certain number of daylight and night landings, and they were going just barely to the edge of night, so they wanted to know when it was technically dark.

Shane Hanlon: 05:56 This would be really cool kind of being, I guess on a base, but like anywhere and having your own, essentially like your own meteorologist.

Nanci Bompey: 06:04 Yeah, you’re right.

Shane Hanlon: 06:05 Right?

Nanci Bompey: 06:05 Your own personal weather person.

Shane Hanlon: 06:07 Just be able to like walk down a hall and be like, “Hey, what’s going …” Yeah, I bet you that wouldn’t get old or anything.

Nanci Bompey: 06:11 Yeah, right. Right. So yeah, so wow, I didn’t know all this about Delores.

Shane Hanlon: 06:15 No.

Nanci Bompey: 06:15 This is fascinating.

Shane Hanlon: 06:16 Yeah, this is amazing.

Nanci Bompey: 06:17 I guess now though we’re going to get more into the space weather stuff.

Shane Hanlon: 06:20 Yes.

Nanci Bompey: 06:20 And if you’ve ever talked to anyone about space weather-

Shane Hanlon: 06:23 Never.

Nanci Bompey: 06:23 … all these space weather researchers, who have such interesting stuff to talk about, but they always mention-

Shane Hanlon: 06:28 Always.

Nanci Bompey: 06:29 … without fail, the Carrington Event.

Delores Knipp: 06:31 It was an event from a great sun spot that appeared on the solar disk in late August of 1859. There had been a concerted effort to draw sun spots, and there were astronomers drawing sun spots. Richard Carrington at the Kew Observatory in Britain would go out every cloud-free day and draw pictures of the projected sun and make a record of the sun spots. While he was drawing this particular sun spot, which he knew was complex, all of a sudden it just blossomed in white light, which when people talk about a white light flare, it is one of the most energetic processes. Usually the flares that we talk about, we’re talking about in portions of the spectrum where humans eyes do not see. But a particularly energetic event will also appear in white light, and it’s white enough to almost obliterate the dark spot. He just could not believe what was happening. He went around the observatory trying to find somebody else to take a look at it. I don’t know that he did. I think there was no one else around.

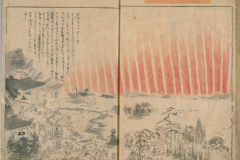

Delores Knipp: 07:44 But interesting enough, simultaneously at a observatory not too far away, another astronomer, a Hodgson, saw the same thing. They ended up talking at a Royal Astronomical Society meeting or some similar type of meeting, comparing notes and going, “Wow, this really did happen. Neither of us was hallucinating.” And furthermore, what they found out was some number of hours later, about 19 hours later, there were huge disturbances at their magnetic equipment. It was sort of the first time between tying those two things together, and then recognizing that there were also auroral reports that were seen all the way down to Venezuela. They were seen in Mexico, Cuba, and I think we’re just now … I don’t know if we’ve actually gotten any records from the Southern Hemisphere.

Delores Knipp: 08:39 That was the beginning, so it was a very fast, what we call coronal mass ejection, just like the one in ’72, maybe a shade slower, but the configuration of it was one that allowed the magnetic field from that bubble to actually be more geoeffective, or meaning that it was better able to interact with our magnetic field and make those very, very equator-ward aurora, and of course, that meant that the entire world got to see the aurora. People who had never seen aurora in Mexico, for example, were seeing aurora, and that became a worldwide event.

Delores Knipp: 09:21 So, people were making records of these, and we’ve just really not had the knowledge that we needed to dig into those records to start understanding how often these things happen. That’s one of the things I’m kind of concerned about now is I’m going, “Well, if people were starting to report these showing up every maybe 70 years, when we thought they were 150, maybe we’re a little bit more at risk than we think.” And so, as a scientist, that helps me go back and say, “Yeah, all of this historical work is relevant.”

Nanci Bompey: 09:56 Yeah, so I guess it’s like, I mean, like a lot of science, like climate science, like other types of science, I mean, understanding the historical context is super important for space weather.

Shane Hanlon: 10:04 Right. Right. I mean, and the Carrington Event is a place where a lot of these things started, or at least our, I guess, observations of them.

Nanci Bompey: 10:11 Understanding, yeah, yeah, yeah.

Shane Hanlon: 10:12 Yeah. Yeah. But, like I said, we needed to talk about the Carrington Event to talk about a lot of her more recent work, and so we were chatting with her, and turns out she had written a story about this storm, this space weather event that occurred in 1967, and this came out, and one of her colleagues from Australia actually sent her this email, really short email, basically said, “Oh, so you know about this one? Have you heard about this other one?” And it turns out there was this event in ’72. There were these pilots flying over a harbor in North Vietnam, and they just started to see over two dozen sea mines just exploding out of nowhere unexplained. They could see them from the plane.

Nanci Bompey: 10:59 Wow. And this is during, obviously, the Vietnam War.

Shane Hanlon: 10:59 Yeah, yeah. No-

Nanci Bompey: 10:59 That’s crazy.

Shane Hanlon: 10:59 It was wild. Nobody really knew what the deal was. That really piqued Delores’ interest, and so she started to dig.

Delores Knipp: 11:12 Well, we were near the end of the Vietnam War. We had been in Vietnam for a very long time, seven years plus, actually. President Nixon was trying to find a way to get the nation out of the Vietnam War and save some face.

President Nixon: 11:27 [crosstalk 00:11:27]. The number of Americans in Vietnam by Monday, May 1st, will have been reduced to 69,000. Our casualties [crosstalk 00:11:35]-

Delores Knipp: 11:34 And the Navy had been telling both President Johnson and President Nixon that the one thing that absolutely needed to happen was that the war goods that were coming into North Vietnam had to be stopped in some way. That was the only way to really bring the hostilities to a halt. The Navy told President Nixon that the way to do that was mine the harbors.

Delores Knipp: 11:59 And President Nixon wanted out of that situation badly enough that he finally gave permission. I think you say “give permission,” why would that be such an issue? Sea mines have and always will be something that you do with great thought because they can kill indiscriminately. But the way President Nixon worked this out was he said, “We’ll drop the sea mines in, and give everybody 72 hours notice to clear out,” because we had the technology at that time to set the sea mines. And so, everybody who was in the port that had been mined had the time to get out if they so chose. Some nations decided not to withdraw. Some ships were perhaps disabled in some way, so there were a number of ships stuck in Haiphong Harbor during that time. And there were smaller harbors to the south that were also mined.

Delores Knipp: 12:59 So yes, there was a political aspect of that. The geophysical aspect, which is what I would write about, was very interesting. I happened, in the course of doing an internet search, come across an image of the sun from the day of the event, and I was completely taken by how intense the sun spot was.

Delores Knipp: 13:26 The sun is an active magnetic star, rather well behaved to many that we see out in the exoplanet world. But it does shed its energy in interesting ways. One way that it sheds its energy is to essentially wind its magnetic field up into knots, as you might think of really, really tightly winding a rubber band. You wind these knots up and then there will be an explosive release of energy. That is exactly what happened.

Delores Knipp: 14:02 So the energy that came out of that particular sun spot was enough to fuel one of the largest flares that I believe we have seen since the great Carrington Event in 1859, and we did not know about that. That was not in any records that had been generally available, but in the course of just searching the internet, I came up with information from Japanese scientists who had used the inability, or the slowdown in our ability to propagate radio waves, to essentially reverse engineer how strong that flare had been. It pretty much goes along with the values from the spacecraft that we had up that saturated, and so we couldn’t see from the monitoring spacecraft, but we could see by reverse engineering, it’s one of the biggest events. But not only does it send out all of that energy, which then immediately disrupts radio propagation, it sends out bubbles of magnetic field.

Delores Knipp: 15:03 And generally, the magnetic field from the sun kind of streams out at a paltry 400 kilometers per second, which is supersonic, by the way. But this particular event, near as we’ve been able to backtrack, and many scientists have been involved in that, came in at close to 3,000 kilometers per second, averaging somewhere between 2600 and 2800 kilometers per second. It is the fastest event that we have on record, even faster than the Carrington storm. It is that speed with which the magnetic field crushed into Earth’s magnetic field that essentially generated the currents that created the magnetic field perturbations that were larger than the threshold for the sea mines, and there we have it.

Shane Hanlon: 15:55 I just have a logistical sea mine question. I don’t know if you know this. You said they set them, and then they have 72 hours to get out. What happens? Do you know what happens to a boat when it bumps up against an unset sea mine? [crosstalk 00:16:08].

Delores Knipp: 16:08 Well, it doesn’t even have to bump up. These were magnetically sensitive mines.

Shane Hanlon: 16:12 Okay.

Delores Knipp: 16:14 The technology had developed so that a sea craft of any kind that had any kind of metallic hull, would have an ambient magnetic field, and the sensor in the sea mine would see that change in magnetic field go by and go, “Oh, that’s a ship.” What we have since been able to figure out is that these sea mines were set at a particular low threshold because the embargo that was going on in the harbors was pretty effective, and it was keeping the large ships out. But the North Vietnamese, anyone, still wants their goods, so they started sending small craft out to where the big ships were anchored, and no, not going to do that either, so they essentially adjusted the thresholds for a number of mines that had adjustable thresholds, and that’s why these sea mines, in particular, blew up. So not all 11,000 of them, but 4,000, which is still substantial.

Delores Knipp: 17:17 But, at the time the Navy had no idea why, and they were going, “Oh, something’s happening here. We don’t know what it is, and if we’re going to keep this embargo in place, we’re going to have to replace all of those, but we don’t want to replace until we know what happened.”

Shane Hanlon: 17:33 Were there any casualties when this happened? Were there …

Delores Knipp: 17:34 Nothing that the US military has reported, but that is all I know. A lot of dead fish, I fear.

Nanci Bompey: 17:44 So, at that time, they didn’t know what set the mines off.

Shane Hanlon: 17:47 They had no idea. I mean, they probably had speculation, but no, they didn’t really know. And there’s no official answer out there right now. That’s really why Delores wanted to dig into it. Like, “Oh, this is probably it.” So, she has an answer, but it’s not like US military official.

Nanci Bompey: 18:02 Ha!

Shane Hanlon: 18:03 Yeah.

Nanci Bompey: 18:04 So interesting.

Shane Hanlon: 18:04 I know.

Nanci Bompey: 18:04 You mentioned also this 1967 event.

Shane Hanlon: 18:08 Yes. In a different way, she also came across this in kind of a chance encounter she learned about this other event. It resulted in a potentially very bad outcome.

Delores Knipp: 18:27 The 1967 event was a little bit more personal for me, although it happened when I was in seventh grade, so it wasn’t immediately personal, but the biggest impacts occurred in the decision-making process at NORAD’s Cheyenne Mountain Complex in Colorado Springs, or just outside of Colorado Springs. I actually worked in that facility in the early ’80s as an officer who was transitioning from doing weather support to transitioning to do space environment support. And there were occasional discussions that I would have with more senior military members where they would say that something happened in the late 1960s that causes us always to have this space environment support system going. But they would never tell me what it was.

Delores Knipp: 19:15 It was only upon the death of the commander of that unit and a chance encounter with people who were just kind of memorializing him, and they called him sort of the Father of Air Force Space Weather. And I go, “Why would you give him that title?” Again, it was a short, cryptic statement where someone said, “Well, you should talk to Colonel So-and-So.”

Delores Knipp: 19:43 And so, I did those … I started those kinds of discussions, emailed, and I was actually able to find the duty forecaster for the day. He told me it was a very rough day. That event came about because the sun does emit in radio, and we also do our reconnaissance, our monitoring on radio frequencies. We use radars to determine if something adversarial is coming over the polar cap. We had, at that time, in 1967, a set of radars. There were three of them called the Ballistic Missile Early Warning System, and they operated on a radio frequency that the Department of Defense believed would get some occasional static from the sun but nothing very large.

Delores Knipp: 20:38 On that particular day, the sun increased its output in the frequency very close to those radars by two orders of magnitude. So, what would normally be 300 units came out as 300,000 units. It essentially jammed those radars. We were in the rise time of the Vietnam War, but more importantly, we were only 10 days out from what would become the Six-Day Arab/Israeli War, and the world was very, very much on edge.

Delores Knipp: 21:16 I believe that the leaders all the way up the military chain thought that things might just be dicey enough that the Soviet Union would attempt to do some kind of a strike. At least that was what had always been practiced in the war games, is that a way a strike, like a preemptive strike would develop is it would start with a jamming of the radars. And so, there it was.

Delores Knipp: 21:43 Fortunately, just a few months earlier we had established, in Cheyenne Mountain Complex, the very first solar forecasting unit, and the person that I mentioned was the duty forecaster on the day. I believe, had we not had that investment in educating people about the space environment and how variable it can be, we may not be here talking today. It was that close in terms of were we going to launch our nuclear-laden aircraft to be ready for the nuclear-laden aircraft that we thought were coming or the ICBMs.

Shane Hanlon: 22:23 I was actually going to ask about that. How close were we? Because I’m picturing every awful action movie I’ve seen where they’re literally … The keys are turned and the briefcases are open, and they’re next to the button. Do we know that?

Delores Knipp: 22:35 What I have gotten from the weather forecasters or support people, from the time, and I’ve talked to three of them, they were aware of pilots and crews who were sent to their aircraft, told to start the engines, and roll the aircraft out to the ends of the runway. That’s close. That’s way close. On the other hand, there was something about the space environment that actually probably, in its own bizarre way, calmed things down. That is the radio propagation situation was so bad that at least some commanders thought that the aircraft might not be able to be called back. And so, rather than go, as I understand it, rather than launch, we held. And there were some very, very busy solar forecasters and commanders of solar forecasters furiously working to help command authorities understand what was going on. They had seen how active the sun had been. Fortunately, the sun had produced, just two days earlier, a very major event, so this didn’t just come out of the blue. These duty forecasters knew that the sun was very active.

Nanci Bompey: 23:50 So you know what these stories have me thinking, Shane?

Shane Hanlon: 23:56 I don’t, but I’m excited to find out.

Nanci Bompey: 23:58 A HBO miniseries.

Shane Hanlon: 23:59 Oh. Oh man.

Nanci Bompey: 24:01 A la Chernobyl.

Shane Hanlon: 24:02 I know, we just talked about Chernobyl recently. I love Chernobyl. I mean, I loved the show.

Nanci Bompey: 24:07 Who would play Delores?

Shane Hanlon: 24:09 Who would play Delores? That’s a really-

Nanci Bompey: 24:11 Like the researcher finding it out.

Shane Hanlon: 24:13 I know.

Nanci Bompey: 24:13 And then you have the … Then it goes back in time to the actual event. This could be good. This could be good.

Shane Hanlon: 24:17 Yeah, it’d be fun. Like, you could like … She would be narrating over it and going back in time. Oh.

Nanci Bompey: 24:22 Yeah.

Shane Hanlon: 24:23 Oh, HBO, if you are listening, you can-

Nanci Bompey: 24:25 We got something for you.

Shane Hanlon: 24:26 Yeah. Just find us at AGU.

Shane Hanlon: 24:31 All right, well that’s all from Third Pod From the Sun for our centennial edition.

Nanci Bompey: 24:36 Thanks so much, Shane, for bringing us this story. Also, our former intern, Jonathan Griffin helped out with this.

Shane Hanlon: 24:42 Yes.

Nanci Bompey: 24:43 And of course, thanks to Delores for sharing her work with us.

Shane Hanlon: 24:46 This podcast was produced by me and mixed by Colin Warren.

Nanci Bompey: 24:51 We would love to hear your thoughts on our podcast. Please rate and review us, and you can always find new episodes on your favorite podcasting app or at thirdpodfromthesun.com.

Shane Hanlon: 24:59 And be on the lookout for more centennial episodes, which we love doing.

Nanci Bompey: 25:03 And as well as our regular episodes.

Shane Hanlon: 25:05 All right. Thanks, all, and we’ll see you next time.