E24 Part 1- (Hope) Diamonds are Forever

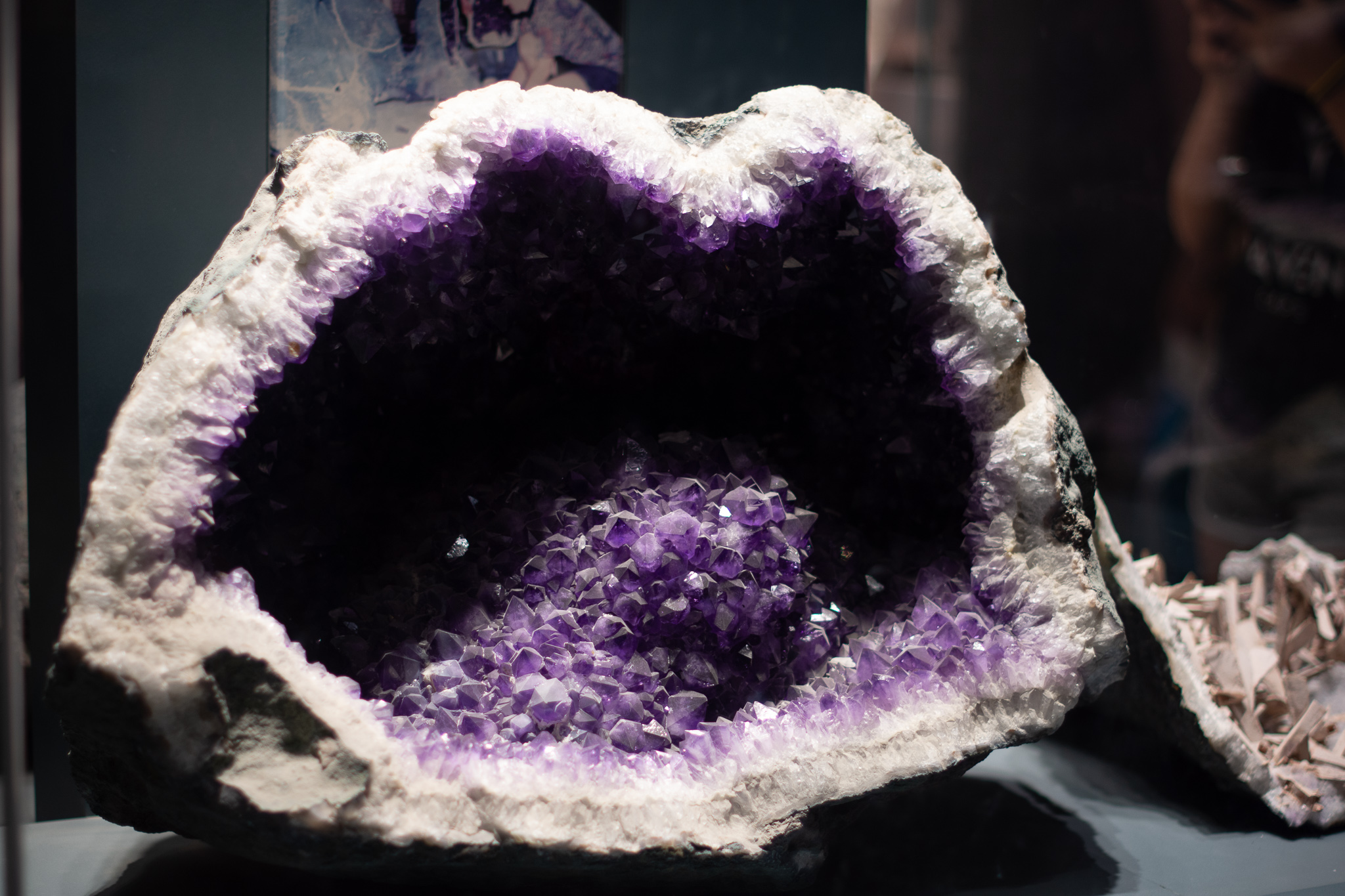

Jeff Post shows the Third Pod team a sample of specimens from the National Gem and Mineral Collection. Credit: Lauren Lipuma.

Mineralogist Jeff Post has a one-of-a-kind job: he’s curator of the National Gem and Mineral Collection, a collection of over 375,000 rock and mineral specimens housed at the National Museum of Natural History (NMNH) in Washington, D.C. In addition to spectacular specimens of rare minerals and crystals, the collection contains over 10,000 gemstones, including the infamous Hope Diamond, one of the most valuable objects on planet Earth.

In this episode, Jeff describes his day-to-day work of maintaining and growing this invaluable collection, which includes being personally responsible for the Hope Diamond and countless other treasures. Listen to Jeff recount the history of the Hope Diamond and its legendary curse and hear how museum curators have made a hall of minerals into a world-class tourist destination.

This is the first episode in a two-part series. Be sure to check out the next episode after this to follow Jeff through the mineral and Gem vaults at NMNH.

This episode was produced by Lauren Lipuma and mixed by Kayla Surrey.

Transcript

Shane Hanlon: 00:00 Hi, Nanci.

Nanci Bompey: 00:01 Hi, Shane.

Shane Hanlon: 00:01 Hi, Lauren.

Lauren Lipuma: 00:02 Hi, Shane.

Shane Hanlon: 00:03 All right, so we’re going back to question time today.

Nanci Bompey: 00:05 Yes.

Shane Hanlon: 00:06 All right. What is the most valuable thing you own?

Lauren Lipuma: 00:12 I would probably have to say jewelry, like family heirloom stuff that has been passed down. Got a few pieces from my grandmothers, although I have to say one time my grandmother gave my sister a pearl necklace of hers that she swore was incredibly valuable and it turns out the pearls were fake.

Nanci Bompey: 00:27 I guess that happens a lot. My mom’s friend is a jeweler and people think they have really valuable stuff and then she brings it to the jewelers-

Lauren Lipuma: 00:34 To be appraised.

Nanci Bompey: 00:35 Yeah, and they’re like, “This is costume jewelry painted with gold.”

Shane Hanlon: 00:43 Welcome to the American Geophysical Union’s podcast about the scientists and the methods behind the science. These are the stories you won’t read in the manuscript or if you’re in a lecture. I’m Shane Hanlon.

Nanci Bompey: 00:52 And I’m Nancy Bompey.

Lauren Lipuma: 00:53 And I’m Lauren Lipuma.

Shane Hanlon: 00:55 Oh, hi Lauren. This is Third Pod from the Sun. I asked about valuable things because our episode today is about one of the, I guess arguably most valuable objects in the world. The Hope Diamond.

Nanci Bompey: 01:13 Is the Hope Diamond like that one in Titanic?

Shane Hanlon: 01:16 Like the movie?

Nanci Bompey: 01:17 Yeah, the movie Titanic.

Shane Hanlon: 01:17 No, it’s not. That’s not a real… Oh, Nanci.

Lauren Lipuma: 01:21 Titanic was fiction, Nanci.

Nanci Bompey: 01:24 I know. But isn’t that like… I know. But was that the diamond necklace she has, with the blue?

Shane Hanlon: 01:28 No.

Nanci Bompey: 01:29 Oh.

Lauren Lipuma: 01:29 No. Well that necklace might’ve actually been based on the Hope Diamond because the Hope Diamond is a rare blue diamond.

Shane Hanlon: 01:36 I’ll never let go Jack.

Lauren Lipuma: 01:37 I’ll never let go. Anyway, back on track. So a few months ago I interviewed Jeff Post who is the curator of the national gem and mineral collection at the Smithsonian Institution and this is a collection of about 375,000 mineral and rock specimens collected from all over the world, including about 10,000 gemstones. And this collection lives at the National Museum of Natural History here in DC. And it’s everything from basic minerals and rocks you’d probably find in your backyard, to giant crystals and really valuable precious metals like gold and silver, and then gemstones. A lot of which were gifted to the collection as pieces of jewelry.

Shane Hanlon: 02:17 I was actually just there a few weeks ago at night. It’s kind of neat.

Nanci Bompey: 02:20 That’s kind of cool.

Shane Hanlon: 02:22 Well, no, I wonder, I’ve been there a few times, but I’ve always wondered, it’s cool to look at, but is it just for show? Is the research, is there some deeper thing than just what we see?

Lauren Lipuma: 02:32 Yeah. Well, it’s actually kind of for both. One of it is to showcase the beauty of the specimens, but there is a lot of research that goes on as well. Scientists from all over the world use the specimens for research, but the Hope Diamond is kind of like the jewel, no pun intended of the selection. The Hope Diamond, so it’s actually a 45.5 carat heart-shaped blue diamond.

Nanci Bompey: 02:53 See not that far from Titanic necklace.

Lauren Lipuma: 02:54 Actually pretty close. Yes. And it’s insured for approximately $250 million.

Shane Hanlon: 02:59 Whoa, $250 million.

Lauren Lipuma: 03:02 Yeah.

Shane Hanlon: 03:03 That’s wild. So Jeff, as the curator, he’s responsible for this priceless diamond and all the other things in there, right?

Lauren Lipuma: 03:11 Yeah.

Nanci Bompey: 03:11 Oh, wow. That reminds me like of the guy who was in charge of the Apollo moon rocks that we interviewed a couple months ago, Ryan Ziegler. He’s like being in charge of this really, almost… Priceless, I guess they say. Like, wow.

Shane Hanlon: 03:25 I would never want that responsibility.

Nanci Bompey: 03:26 No.

Lauren Lipuma: 03:27 Yeah, no, me neither. I mean the Hope Diamond is amazing and it’s on display. Like Shane, you just went to see it. I’ve seen it. Anyone can walk right up to it and look at it, but the collection has so many other really valuable, rare, beautiful minerals and rocks that a lot of people don’t get to see. So some of them are on display in the museum, but the vast majority of the specimens are actually housed a couple levels up above the main floor of the museum in boxes and drawers. And Jeff was actually kind enough to give me and a few of our colleagues a tour of the collection. He even brought us into the vault where they keep the very valuable things.

Lauren Lipuma: 04:00 And so that is what we will get into in part two of this episode. But right now in part one, Jeff is going to tell us about the Hope Diamond, about its history and about what his job is like being responsible for this item.

Jeff Post: 04:18 So my name is Jeffrey Post and I am the curator of the National Gem and Mineral Collection at the Smithsonian Institution. I am also a research mineralogist here and currently chairman of department of mineral sciences.

Lauren Lipuma: 04:31 So what does that mean exactly? What is your job as curator do?

Jeff Post: 04:35 Being the Smithsonian, part of the job here is helping to take care of and build that collection. And so for the last 25 years or so, I’ve been curator of the collection, which means sort of providing the leadership to hopefully, take the collection to the future and make sure the collection is getting used by people who need to use it.

Jeff Post: 04:54 And so a typical day is spending time helping people use the collection, sending out samples, acquiring new materials for the collection, working on whatever arrangements you have to make to have things come and go out of the collection, supervising the collection managers that work with the collection. Also trying to spend a little time doing my research.

Lauren Lipuma: 05:15 And so what are some of the individual research that you’re doing?

Jeff Post: 05:18 There’s a couple areas of research that have sort of defined my research career and they’re about as opposite end of the mineral spectrum as you can get. One is, sort of a major part of my research has been environmental mineralogy. So looking at minerals that are found in soils and sediments that occur as coatings on surfaces of rocks are associated with streams and rivers and oceans. And these are the minerals that occur at this interface between the solid earth and the living ecosystem that we all are a part of. So working on some of the ugliest and sort of grungiest minerals in the world is part of my interest.

Jeff Post: 05:57 And then the other side of the spectrum is working on diamonds. Turns out diamonds are fascinating materials, not only because of where they come from. They come from a part of the world that we can’t directly access. They form more than a hundred miles below the surface of the earth. And so diamonds coming to the surface are a little bit like meteorites coming from another planet. They’re telling us about a world, place that we can’t directly go to. Frankly, what kind of got me into that was the Hope Diamond. I mean the Hope Diamond is this large blue diamond.

Speaker 5: 06:30 In the untold centuries since it was formed in the heart of the earth. This gem of gems has captivated Kings and Queens, showgirls and socialites.

Lauren Lipuma: 06:42 So tell us a little bit about the story of the Hope Diamond for someone who doesn’t know anything about it.

Jeff Post: 06:50 Well, the Hope Diamond. People come here and they have all heard of the Hope Diamond and you walk into the gallery and you look in the case and you probably did this, you go, okay, there’s this little diamond in there. Well, it kind of know most people are thinking it’s got to be something about the size of a softball. Because we’ve all heard about the Hope Diamond. Most common misconception is it’s the largest diamond in the world. It’s not. It’s 45 and a half carats. It’s bigger than most people’s engagement rings, but it’s by a long shot, not the largest diamond in the world. A tenth of the size of the largest diamond in the world.

Jeff Post: 07:24 So what makes it so interesting? Why is it so valuable? Why is it so famous? Okay. It’s a blue diamond. It’s the largest natural blue diamond that we know of, this facet blue diamond. The fact that it’s blue means it has a whole interesting geology story, but it also means that it’s always been a very unusual diamond throughout it’s history. And because it’s this unusual blue color and size, it’s a diamond that we can trace back its history.

Jeff Post: 08:01 It’s hard to lose a large blue diamond in history. If it’s a colorless diamond, if somebody re-cuts it, if it gets stolen, it gets sold. It’s hard to trace it because there are a lot of colorless diamonds out there and they all kind of look alike. But large blue diamonds have always been very rare. And so throughout history, when somebody sees a large blue diamond, that’s a big deal, and they write about it, they notice it, they talk about it. And so we can follow the history, therefore, of this diamond back better than we could most diamonds. And so we know from that now this blue diamond originally was found in India probably in the middle, late 1600s.

Jeff Post: 08:40 It was sold in 1668 to King Louis the 14th of France. He bought it, it was 113 carrots. So about two and a half times as big as it is now. He had it re-cut into a heart-shaped stone that was about 69 carats. It became part of the French crown jewels.

Jeff Post: 09:01 In 1792 during the French Revolution, that diamond was stolen along with all the French crown jewels. Almost everything else of the French crown jewels were recovered in or around Paris. One piece was never ever seen again was the piece of jewelry that had the blue diamond do. It disappeared.

Lauren Lipuma: 09:20 Wow.

Jeff Post: 09:22 And about 20 years later, in 1812, a blue diamond appears for sale in London. It’s 45.5 carrots, the same diamond that we know today as the Hope Diamond and suddenly out of nowhere, here’s this blue diamond being described as being now for sale, suddenly the finest blue diamond ever.

Jeff Post: 09:40 And eventually it gets acquired by a private collector in about 1821 or 22, Henry Phillip Hope, and that’s where the name comes from, the Hope Diamond. It now becomes part of his collection. Well, interestingly, in all the reading you do about blue diamonds and major diamonds in the world at that time, they still talk about this blue diamond that’s part of the French crown jewels and this blue diamond that is now in Hope’s collection in England. And it wasn’t until the late 1850s that somebody finally said, “You know what? That one that was in France, we now know was stolen. It’s probably this diamond that Hope had, it’s probably the recut version of that.” They finally made that connection.

Lauren Lipuma: 10:23 Who was the person selling it in London?

Jeff Post: 10:25 He was a gem dealer by the name of Eliason. He’s a well-known diamond dealer. And how he exactly acquired it, we don’t know, whether it was directly from the person who stole it or whether it changed hands a few times. It was recut, obviously. It went from a 69 carat heart-shaped stone to the 45 and a half carat cushion shape in 1812. So whether it was cut to simply disguise it so that nobody had to answer questions about whether this was the French blue or whatever reason, it was re-cut.

Jeff Post: 10:52 And so until the 1850s, no one finally, at least in writing said, “You know what? These are probably the same stone.” And so after Hope died, it stayed in his family until about 1900. It was sold by one of his heirs. And then eventually it was sold by Pierre Cartier, French merchant in Paris. And it was sold to one of his good customers, a woman named Evalyn Walsh McLean. Evalyn Walsh McLean lived here in Washington, DC and that’s what brought it here to this country.

Jeff Post: 11:23 And she was the daughter of a gold miner, actually a gold silver miner in Colorado. Struck it rich and moved his family here to Washington DC, and so she grew up here and married the son of the owner of the Washington Post newspaper. So there was two fortunes that kind of got pulled together here. And so they would travel to Europe and she would stop to see Pierre Cartier and always buy some spectacular piece of jewelry from him. So on one of her visits he showed her the Hope Diamond. She didn’t buy it at that time, but Pierre Cartier, not one to give up easily, he brought the diamond here to Washington, DC in a new setting, left it with her on a Friday afternoon and just said, “Here, wear it around the house for the weekend. I’ll come back Monday and we’ll talk.”

Lauren Lipuma: 12:12 Wow.

Jeff Post: 12:13 And so she was absolutely mesmerized by the diamond, convinced that she had to own the diamond.

Shane Hanlon: 12:18 The Hope Diamond. Okay. The Hope Diamond is rumored to be cursed, right?

Lauren Lipuma: 12:26 Yeah, it was. So people thought that misfortune or tragedy would be fall anyone who owned it or who wore it. But what Jeff actually told me is that these rumors were false and they were probably just fabricated to drum up interest in the diamond and to increase its value.

Jeff Post: 12:42 Well, it’s only in the 20th century that people even start talking about the possibility of this diamond having bad luck associated with it. It’s a totally new part of the story of the Hope Diamond, but Evalyn Walsh McLean was one that really liked to talk about that. And Pierre Cartier we think certainly enhanced that story to get her interested in it. But when we look back, well, where did this curse story originate? The earliest mention we can find anywhere is in 1908. There’s a news story that comes out in the New York Post and it’s about this blue diamond that’s owned by Frankl and Sons, a jeweler in New York. It’s in their vault and it goes on and on about all the dark secrets of this diamond and things it could do to somebody if it got out of this vault and all this kind of stuff.

Jeff Post: 13:30 And it’s pretty clear when you look at the context, this was a time when there was a recession going on in the United States. Diamond prices were down and any publicity is good publicity, right? So here’s Frankl and Sons, they’ve got this diamond sitting in the vault, they can’t sell it. What do you do? You get a newspaper article written about it. And so it’s completely fabricated. But here we go. And that seems to be the origin of the whole curse thing. And of course, once it’s in the newspaper, then it just gets picked up and every time the story is told, it gets a little bit bigger and better. And various people start cashing in on that story and write books about it and there’s a little movie done on it and everything else.

Jeff Post: 14:08 And so that all becomes part of now the common lore. So Evalyn Walsh McLean kind of adds to it by the fact that despite all of her wealth, she had a lot of pretty sad things happen in her life. She lost a son in an automobile accident. Her daughter committed suicide. Her husband ended up in an insane asylum. And so for people who like to believe in curses, they’re going, “Well, look at all these terrible things that happened with this rich lady. It must be the curse.” Well, she died at a relatively early age as well, and her collection then was sold to Harry Winston in New York.

Speaker 6: 14:44 In New York, a million dollars worth of jewels is he being delivered to gem dealer, Harry Winston. The collection of the late Evelyn Walsh McLean. The chief treasure is the famous blue white Hope Diamond. I say famous, but perhaps a better word would be notorious, for the stone has a history of ill luck going back over 300 years. Legend has it that a curse rests on whoever owns the Hope Diamond. It’s a marvelous jewel even if tragedy has usually attended its flashing beauty.

Jeff Post: 15:15 And Harry Winston, he liked to tell a story or two about a gemstone as well. So he traveled the Hope Diamond around the United States for about 10 years as part of what he called his Court of Jewels exhibit. And so a lot of people in the United States got to see this diamond as it traveled around. In fact, he’d go into small towns and they’d have a special showing, if there was a local charity event or whatever, the wife of the mayor would wear the Hope Diamond and get her picture in the paper and it was all good promotion for the charity, but also for the Hope Diamond.

Jeff Post: 15:43 And then finally in 1958 then he decided to give the diamond here to the Smithsonian with the idea that we could start this great national gem collection. And so by that point, a lot of people heard of it. People still knew about Evalyn Walsh McLean. It’s hard to find a picture of her without her wearing the Hope Diamond. So her eccentricity with the Hope Diamond kind of added to the story. So it was something that people had heard of and for whatever reason when it came here to the Smithsonian, it just really resonated with people. You always wonder why is it this thing just becomes so fascinating to so many people.

Jeff Post: 16:17 But when it came here, it really put this museum on the map as a destination for people in Washington DC. And for whatever reason, it became the must see item here. And it became sort of the core, the beginning of our great national gem collection. The collection grew. More people got interested in this idea of building a great national gem collection. It’s like, “Yeah, I’d like to be part of that too. Let me give something.” And suddenly we’ve got one of the great collections of the world.

Shane Hanlon: 16:49 All right, so you said you said researcher.

Lauren Lipuma: 16:52 Right.

Shane Hanlon: 16:53 But it sounds more like caretaker. I don’t mean that disparagingly.

Lauren Lipuma: 16:59 That is part of his job.

Shane Hanlon: 16:59 Oh, okay. But like what’s the research about it? How does one research a rock?

Lauren Lipuma: 17:03 Very carefully, actually. Especially when it’s a priceless heirloom.

Jeff Post: 17:07 The good thing about the Hope Diamond being here is that we can study it. And the good thing about being the curator of the collection is I can study it. And so the instruments were set up here in the department. We brought the Hope Diamond off exhibit, took it out of its setting, we spent a night analyzing the Hope Diamond. We used an instrument called a time of flight secondary ion mass spectrometer, which we had here in the department.

Jeff Post: 17:31 With that instrument we could directly measure the amount of boron in the diamonds. The first time that measurement had ever been done.

Lauren Lipuma: 17:37 When did you do this?

Jeff Post: 17:37 We did that about three or four years ago, or five years ago now. And so, we literally sputter off a few millions of atoms off the bottom of the Hope Diamond. So it’s a little lighter, but it’s just a few millions of atoms. And from that we could measure the amount of boron. And so we found on average about a half a part per million of boron in the Hope Diamond. That’s what gives it the blue color. And the other interesting property the Hope Diamond has is when you expose it to a short wave ultraviolet light in a dark room, and then you turn off the light, the diamond glows this bright orange color and it will glow bright orange for about a minute. And you can imagine for people who believe in curses on diamonds thinking, “Oh my gosh, it’s glowing this blood orange color.” It’s just like too good to be true. We know it’s not the curse so it turns out it’s the boron that also causes this phosphorescence.

Jeff Post: 18:29 And so we’ve been doing measurements of the phosphorescence. It turns out that every blue diamond that we’ve measured has similar spectra that we can… Because now we have very sensitive spectrometers, we can measure this phosphorescence and the details in these spectra, again, give us information about the boron in the diamond, how it’s there, the behavior, the electronic transitions going on. So turns out that for a simple material, there’s just all kinds of interesting things and the earth does it differently than the ones that might be made in the laboratory.

Shane Hanlon: 19:00 All right, so that’s one specimen. Let’s say. I’ve been to the museum, but I’m sure not everything’s out. Like how many, what are we talking about here? How many are there? Like a couple of hundred?

Lauren Lipuma: 19:10 Oh, so many more. So on exhibit, there’s 3000 but the entire collection is 375,000.

Shane Hanlon: 19:17 What?

Lauren Lipuma: 19:18 Yes. I mean, most of them are sitting in drawers and cabinets. They’re not like gem display quality. But in part two of this episode, which we’ll get to you, we actually go into the vault where all the cool stuff that’s not on display lives.

Shane Hanlon: 19:30 Okay, so before we get there though-

Nanci Bompey: 19:32 Remember Gem, the cartoon?

Lauren Lipuma: 19:35 I do. Gem in the-

Nanci Bompey: 19:36 Gem, She’s truly outrageous.

Lauren Lipuma: 19:37 What was her band or her-

Shane Hanlon: 19:38 Was that Nickelodeon?

Nanci Bompey: 19:39 I don’t remember.

Shane Hanlon: 19:40 I didn’t have cable growing up.

Nanci Bompey: 19:41 Oh.

Lauren Lipuma: 19:46 Gem and the Holograms.

Nanci Bompey: 19:48 Yes.

Shane Hanlon: 19:48 Oh my goodness, okay. Moving on. No, no, no. I want to know. So there’s only, there’s one… I can’t do this math on the fly, like a fraction out of what’s behind.

Lauren Lipuma: 19:56 Right.

Shane Hanlon: 19:56 So like what’s the story there? How do they determine what comes out, what doesn’t? How do they even get them in their collection? There’s a history there, right?

Lauren Lipuma: 20:05 Right. They want to include stuff about the actual specimens history when they put them on exhibit.

Jeff Post: 20:10 The first thing you do is you really think about what are the stories, the messages you want to get across. I mean, you understand, clearly I work on minerals and so I’m picturing minerals and picturing crystals and you’re kind of going, “Okay, what is it we want people to learn from our exhibit when they leave here? How do we want them to be changed, to be different? What kind of impact do we think these stories can have on people? What do we think is important that people learn about these materials?” And so once you’ve created that concept, then you go through the collection. You kind of go, “Okay, what’s the best way to tell this story?”

Jeff Post: 20:42 And some cases it’s obvious, but ultimately the thing we knew for sure is we wanted the specimens to be the storytellers. We didn’t want people to come into this gallery and just be reading a lot of labels on the wall or looking at a bunch of computer screens. We got the real things. Nowadays you can spend your whole life looking at the world on a computer screen or a phone screen or whatever it is.

Jeff Post: 21:12 It’s funny, I think people in some ways are almost more excited to see our exhibits than maybe there was the time in the past, because it’s like suddenly everything’s three-dimensional again. It’s like the real things and you’re so used to seeing images and you’re seeing everything in pictures and everything that you kind of, there’s a whole different sensation now you’re going, “Wow, that is the real Hope Diamond. It’s the real big chunk of quartz crystals. It’s a real…” And that has an impact in a way I think that really helps to sell the story, because a picture just doesn’t have that same impact. It’s two dimensional. It’s ephemeral. It’s electronic. It doesn’t have a soul. It doesn’t have a personality. It’s not there. Whereas when you stand in front of that mineral specimen, it has a personality.

Jeff Post: 22:06 So the exhibit hopefully is just a beginning. It’s a place where people can start to be awakened to this whole excitement of minerals in the earth and geology and the story of this planet we live on and hopefully now they’re going to want to find other places to follow up with that.

Lauren Lipuma: 22:22 What is it like for you to hold some of these specimens to work on them? Something like the Hope Diamond or some of other, you know?

Jeff Post: 22:29 It’s a thrill and a privilege. It really is. I’ve had various reasons, for example, to hold the Hope Diamond dozens and dozens of times in the last 35 years, whatever. But every single time I put it in my hand, there is this, first the sense of isn’t it incredible that this one diamond here has gotten so much interest, that its got so much history that there’s movies and books and over and over again. It’s the first question people ask you about. It’s just that this thing does that, isn’t that pretty amazing? And then you go, think what this thing is worth. There’s more value in that volume right there than almost anything else in the world.

Jeff Post: 23:15 I talk to gem dealers sometimes and they’re selling gems and so to them, you know, the gem is worth a certain amount of money and if something happens to it, it’s insured and they get that money back. It’s not a loss. And so they’re sometimes giving me a hard time going, “Why are you being so persnickety about this? I mean, it’s just a gem, you know, it’s insured.” And I’m going, “Yeah, okay, wait. It’s just a gem. But this gem is one that everybody in the world knows as part of our collection. I can’t replace this gem. I don’t care how much money you give me, I can’t replace it. This is an iconic gemstone. It may be the best in the world. Maybe it’s not the best, but it’s the one everybody knows. It’s the one everybody wants to see. It belongs not to me. It belongs to everybody in the world.” It’s a little bit scary.

Jeff Post: 24:00 I mean, I’ll be honest with you, there’s a certain part of me that goes, someday when I walk out of here, I mean it’s going to be a really sad, horrible day when I finally have to say I’m leaving the Smithsonian, but when I do that, the one sense of relief in a way is that, you know what? It’s now somebody else’s responsibility because there is a responsibility to looking after something that is more than just research specimens, more than just commodities. It’s something that belongs to all of us that we all share in.

Nanci Bompey: 24:31 You know, what’s so interesting about this? We were talking in the beginning about how similarities to Ryan who curates the Apollo moon rocks, he said the exact same thing. That it’s not just, yes, it’s a big responsibility, but it’s like this responsibility that it’s for all of us. That’s why it’s also such a big, ah, so beautiful. But it’s like they feel this weight because it’s not just doing it for NASA or in this case doing it for the Smithsonian. It’s doing it for like humanity.

Lauren Lipuma: 24:58 For the world.

Shane Hanlon: 24:58 Man. Do you think we’re doing this podcast for humanity?

Nanci Bompey: 25:01 Yeah, absolutely. That’s the sense of-

Lauren Lipuma: 25:06 We are making the world a better place. [crosstalk 00:25:07].

Shane Hanlon: 25:07 Our podcast is so important.

Lauren Lipuma: 25:09 One podcast episode at a time.

Nanci Bompey: 25:12 Somebody’s got to do it.

Shane Hanlon: 25:14 Oh man. All right all, that’s all from Third Pod from the Sun.

Nanci Bompey: 25:18 Thanks so much to Lauren for bringing us this story and thanks to Jeff for sharing his work with us.

Shane Hanlon: 25:23 This podcast was produced by Boren and mixed by Kayla Surrey.

Nanci Bompey: 25:28 We’d love to hear your thoughts. Please rate and review us. Listen to us wherever you get your podcasts or at thirdpodfromthesun.com

Shane Hanlon: 25:36 All right. Thanks all and we’ll see you next time.

Nanci Bompey: 25:45 Gem. She’s truly outrageous. Truly, truly, truly outrageous.

Shane Hanlon: 25:53 Oh, we’re going to have a lawsuit on our hands.