E24 Part 2- A Walk in the Vault with Jeff Post

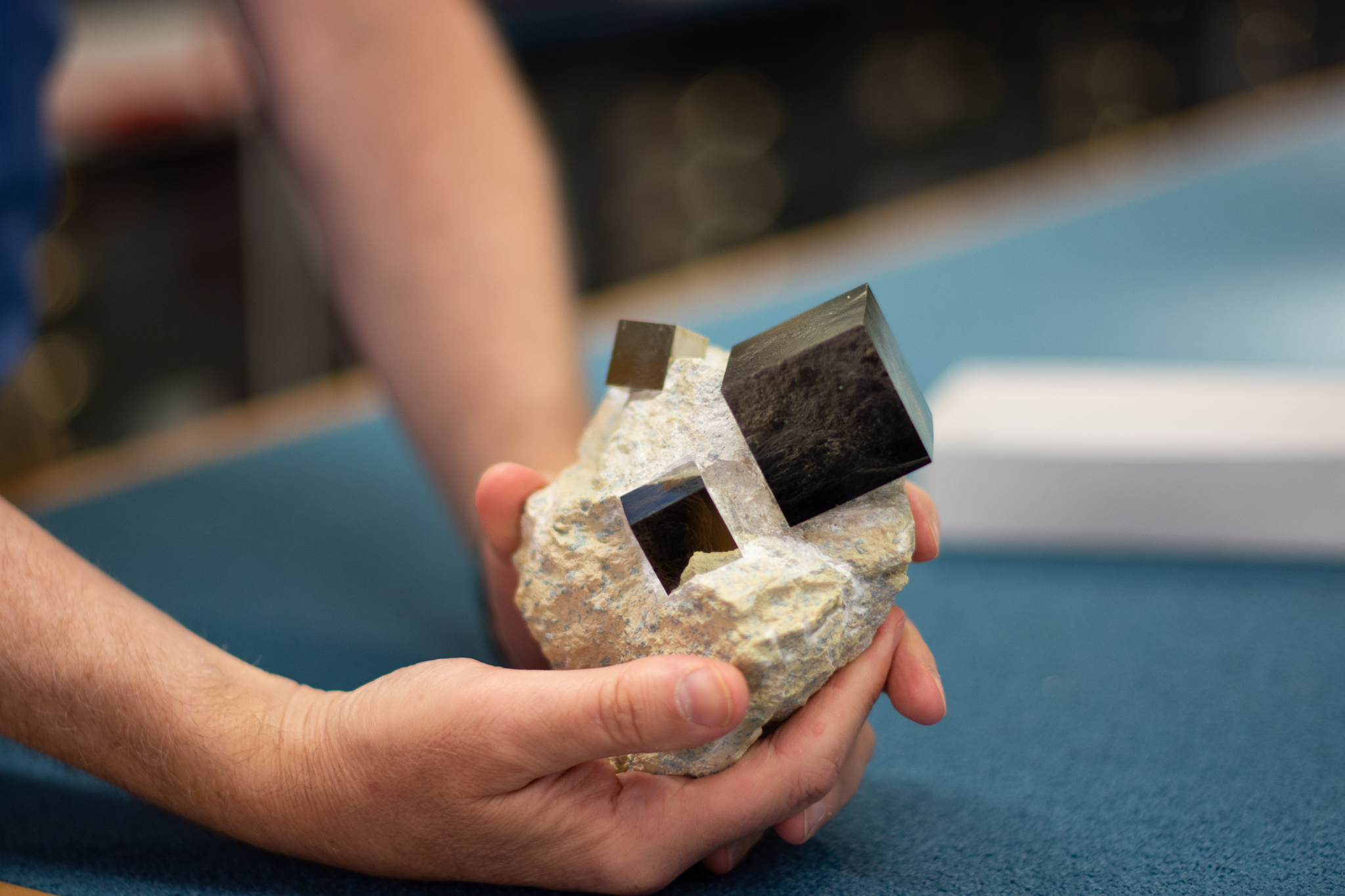

Jeff Post shows the Third Pod team a sample of iron pyrite (fool’s gold) with large, square crystals.

Credit: Lauren Lipuma.

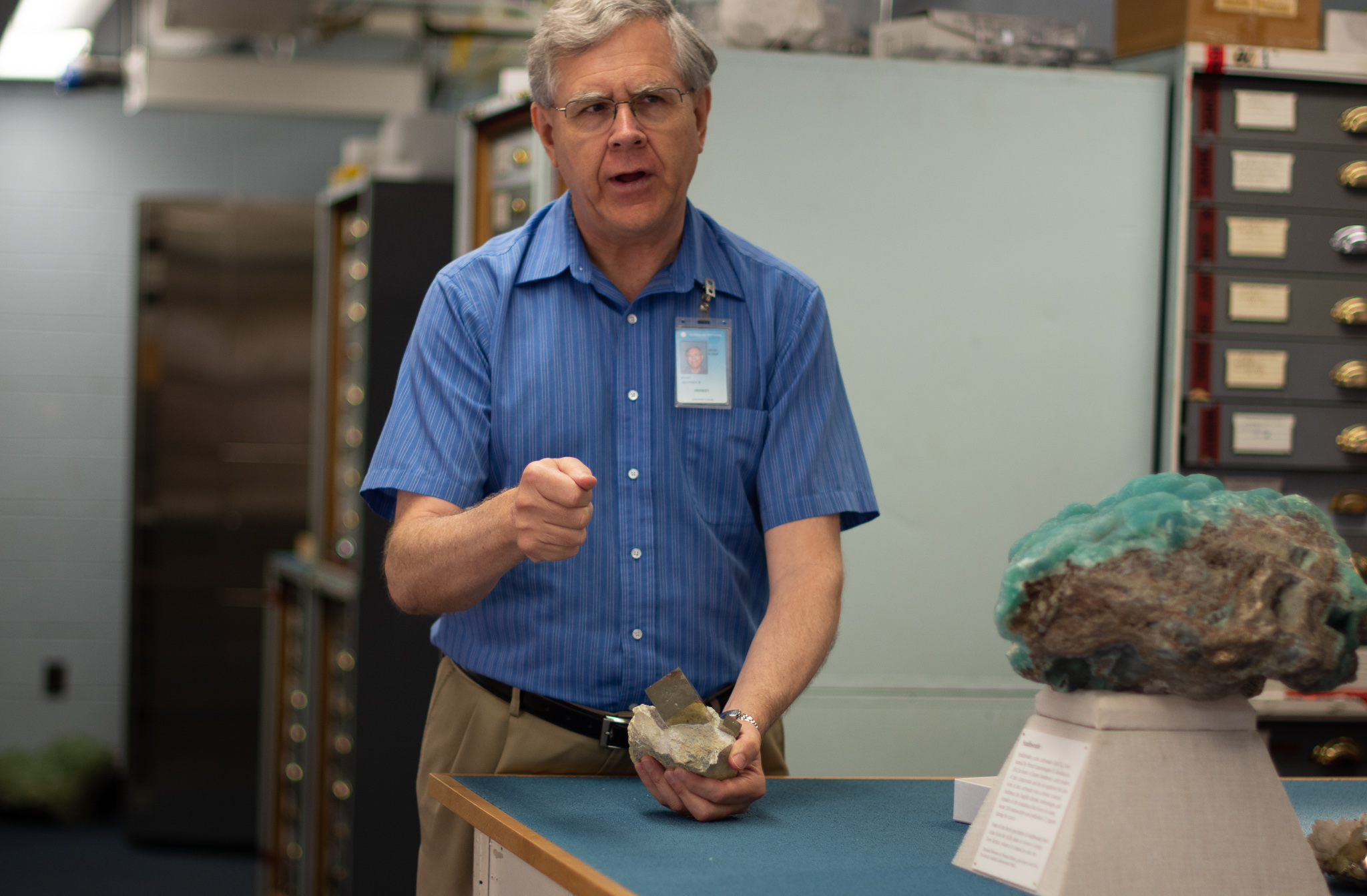

Mineralogist Jeff Post has a one-of-a-kind job: he’s curator of the National Gem and Mineral Collection, a collection of over 375,000 rock and mineral specimens housed at the National Museum of Natural History in Washington, D.C. In addition to spectacular specimens of rare minerals and crystals, the collection contains over 10,000 gemstones, including the infamous Hope Diamond, one of the most valuable objects on planet Earth.

In this episode, Jeff takes Third Pod producers on a tour of the vault, where the collection’s most valuable and rare specimens are kept. Jeff shows us a 266-carat diamond; 12 ounces of pure gold; a nugget of osmium, the densest known metal; and countless rare gemstones, including a smoky quartz the size of a newborn baby. Jeff also tells us about the largest diamond ever found and the story of a diamond necklace given by Napoleon to his wife, Empress Marie Louise, to celebrate the birth of their first son.

This is the second episode in a two-part series. Be sure to check out the previous episode to hear about the history of the Hope Diamond.

This episode was produced by Lauren Lipuma and mixed by Kayla Surrey.

Transcript

Shane Hanlon: I have master of the house stuck in my head.

Nanci Bompey: Why?

Shane Hanlon: Why? Because I’m just thinking like…

Nanci Bompey: Master of the house.

Shane Hanlon: No. Master of the vault, keeper of the gems, going to do some science on some pretty rocks.

Lauren Lipuma: Nice.

Shane Hanlon: Welcome to the American Geophysical Union’s podcast about the scientists and the methods behind the science. These are the stories you won’t read in a manuscript or hear in a lecture. I’m Shane Hanlon.

Nanci Bompey: I’m Nanci Bompey.

Lauren Lipuma: I’m Lauren Lipuma.

Shane Hanlon: Hi Lauren. This is Third Pod from the Sun.

Shane Hanlon: This is part two of a two-part interview that Lauren did.

Lauren Lipuma: Right, this is part two of our interview with Jeff Post, who is the curator of the Gem and Mineral Hall at the Smithsonian’s Natural Museum of Natural…

Nanci Bompey: Wait, Museum of….

Shane Hanlon: Museum of Natural History.

Lauren Lipuma: Sorry, National Museum of Natural History here in DC.

Shane Hanlon: National, it’s a fed thing.

Lauren Lipuma: Yes. That one’s always a mouthful for me.

Shane Hanlon: If you haven’t listened to one, go back and listen to it, it’s right before this one. This one, we’re going to be talking about going through the vault. Have you ever? I guess you have Lauren, but Nanci, have you ever been inside of any sort of a vault before?

Lauren Lipuma: Like a bank vault, maybe?

Shane Hanlon: Like a bank vault.

Nanci Bompey: I don’t know. The bank-

Shane Hanlon: I was in a place the other day that the bank vault door was in the bathroom because the place used to be an old bank.

Nanci Bompey: I’ve been in there. I think there was a bar in New York where you-

Shane Hanlon: Of course there was.

Nanci Bompey: They turned it into a bar, and you sat in the vault.

Lauren Lipuma: That’s really cool.

Shane Hanlon: Someone who’s done it, Lauren, what’s it like to walk through a vault?

Lauren Lipuma: It’s great. After we talked to Jeff about his work as a curator, we were so lucky, he took us back into the vault. This is where they keep all the specimens from the gem and mineral collection that are valuable, but they’re not currently on display. Things get rotated out a lot from the vault area and on display, on exhibit. There’s actually two parts to this vault. First when you walk in, there’s a big room, and this is where they keep about 20,000 or so specimens.

Shane Hanlon: It’s like the waiting room area for the vault.

Lauren Lipuma: Wait. Actually, that number might be wrong, but it’s where they keep a lot of specimens. You walk in and there’s just big glass cabinets lining the walls, and a big work table in the middle, and there’s just the most beautiful rocks and crystals you have ever seen in your life in this room. It’s amazing. It’s quiet. It’s very serene.

Shane Hanlon: Now I’m disappointed I was gone when you did this.

Nanci Bompey: Wait, that’s not the main vault part?

Lauren Lipuma: There’s two parts to the vault. That is the main vault, but there’s a smaller vault within that vault, and that’s where they keep the gems.

Nanci Bompey: Did it have a lock on the vault?

Lauren Lipuma: Yeah. Of course. There’s many layers of security.

Shane Hanlon: I’m going to have a side stitch.

Nanci Bompey: How big is that vault?

Lauren Lipuma: Let’s see. The gem vault is probably, I would say, about the size of two elevators.

Nanci Bompey: Oh, pretty small.

Lauren Lipuma: It’s small, it’s a small room. It was a very tight fit. There were four of us inside there, and it was a tight fit. The main vault is big. It’s hard to give the size of a room. I’m not good at square footage, but probably the size of a classroom, I would say, a small classroom.

Nanci Bompey: Just like a regular room, but the other one’s legit vault.

Lauren Lipuma: It’s a vault, yes.

Shane Hanlon: Legit vault.

Lauren Lipuma: There’s lots of doors and keypads and things like that.

Jeff Post: This is our vault area. It’s our high security storage area for the mineral collection, and back around the corner is where the gem vault is. This is a space that four of us have access to. You can see there’s cameras here, everything. It’s a high security area. We’ve pulled from our mineral collection about 20,000 specimens that are considered to be higher value, more special, more fragile, just needing extra security, extra care. It’s also our main work area. This table area is where, as new things come into the collection, we typically will unpack them here, let them sit here for awhile while we go through the accession process because it’s very limited access, we don’t have to worry about people coming in and messing with them and picking them up, things they shouldn’t be doing. Again, a lot of these are valuable. A lot of these are fragile.

Jeff Post: Most of the specimens in here are in the drawers, but the bigger specimens that don’t fit into the drawers are in these cabinets. They give you kind of an idea of the sorts of minerals that are here in this room. We try to keep our very best specimens on exhibit for the public to see, but what’s back here might be second best or equal to what’s out there, or new things that are coming into the collection.

Jeff Post: Part of our mission here also is preserving some of Earth’s great treasures. When you look at these crystals, the colors, the forms, the reason they’re back here is because they have a high market value. There are collectors around the world that will pay large chunks of money to own specimens like these. Each one’s one of a kind. It formed naturally in the Earth, and in many cases their forms, their colors or such, they’re just beautiful things. You’ve got people who are buying these, like art. Instead of buying paintings or sculptures, they’re buying beautiful mineral specimens and they’re displaying them in their homes.

Jeff Post: It’s interesting when they talk about it, they’re using the same kind of terminology. It’s the same kind of financial thinking, as with artwork, only applied to minerals. Many of the people may not know much about the science behind it, but they just know they’re beautiful things. We don’t get a lot of people in this room because this is a high security area, but most people, when they see these for the first time, they’re kind of going, “Oh my gosh, these things came out of the earth like this.” You’re going, “Whoa.” That’s the same reaction that our visitors have when they see them out in the exhibit hall.

Jeff Post: We get millions of people a year coming through our galleries, and we figure at the end of that, if any small percentage of them, because of this experience with the minerals are going home and going, “Wow, I want to either study these things or at least I’m open to learning more about them,” or “The next time I see an article about geology or about minerals or about global change, whatever it is, I’m going to read it because suddenly this earth is a whole more interesting place than it used to be.”

Shane Hanlon: Lauren, before you actually did the interview, what were you envisioning that you would see? What were you most looking forward to?

Lauren Lipuma: I was really envisioning a bank vault, I guess, not that I’ve ever seen a bank vault, but something very sterile and white and metal. It wasn’t like that at all. It was like…

Nanci Bompey: Like Mission Impossible?

Lauren Lipuma: Yes, that is exactly what I was picturing. But it wasn’t at all.

Shane Hanlon: You have Tom Cruise dropping from the ceiling?

Lauren Lipuma: Right. It was very warm with these beautiful wood cabinets, and there’s this green carpet everywhere.

Nanci Bompey: That I wouldn’t expect either.

Lauren Lipuma: It was really great. I also should mention, I was there with our colleagues, Katie [Brendel 00:06:43] and our former intern Abigail. You’ll hear their voices on this interview, as well, but it was really cool. I didn’t even think about this, but he showed us some really valuable things. He showed us diamonds and gold and other really precious metals and things.

Shane Hanlon: You didn’t walk away with any of them?

Lauren Lipuma: Nope.

Jeff Post: Just a couple of things that are kind of fun here. This is one that I think is kind of neat. Here, let’s go over to the table. Feel this. Put that to your cheek.

Lauren Lipuma: It’s very soft.

Jeff Post: And it feels what, warm, cold?

Lauren Lipuma: Cold.

Jeff Post: Cold, very cold. That is 266 carets of diamond.

Abigail: What?

Katie: What?

Jeff Post: It’s probably the biggest chunk of diamond you’ll ever hold in your hand. It’s a cluster of diamond crystals from the Congo. In addition to being the hardest known material, diamond is also the best known conductor of heat. It feels cold because when you pick it up, it’s sucking heat away from your hand so fast that your hand feels cold. Of course, it also means that it’s sucking heat away, it warms up real quickly. You guys, all your heat is now in this diamond. It’s warmed up again.

Jeff Post: If you look and hold it up the light, you’ll see it’s actually got some pretty clear areas in there. They could probably have cut stones out of this, but because it’s such a big cluster of crystals and so unusual, it’s worth way more to a collector this way than it would be for any gemstones that could come out of it. It’s just a really intriguing chunk of diamond, isn’t it? You’ll hear us talk about diamond having a greasy luster, and when you see a big piece like this, you can see it really does have this sort of a greasy look to it, doesn’t it?

Lauren Lipuma: Mm-hmm (affirmative). Like slick.

Jeff Post: But it just feels good, doesn’t it? What else? A one carat diamond you can’t do that. [laughing] Again, you never know what you’re going to find. This you’ll recognize, this is the one we have because we often have school groups we go talk to you, but here, so what do you think? What is that?

Abigail: Gold.

Jeff Post: There you go. Now pick it up.

Abigail: Oh my gosh.

Lauren Lipuma: Whoa, yeah. It’s way heavier.

Jeff Post: Even though I know gold is dense. You know it is. Every time I pick it up, it still surprises me because we’re just not used to holding something that size, that’s that heavy. That’s a nugget from Australia about 12 ounces, and it was found by a fellow with a metal detector.

Jeff Post: We bought it way back when gold was much lower price than it is now. We thought what a great educational specimen because it’s the kind of thing you can let a bunch of school kids pass around. They can’t hurt it. This is a big solid nugget. As long as they don’t whack each other with it or something, nothing bad can happen. Most people have never had a chance to hold a big nugget, so we thought for an educational piece, what a great thing. Plus we didn’t have a good nugget from Australia, so it actually filled a piece to my collection, too.

Jeff Post: Actually, here’s something else that’s kind of interesting. Gold is very dense. A piece of gold is very heavy. Do you know what the densest metal is, the densest known metal?

Abigail: Platinum?

Lauren Lipuma: I want to say lead or mercury.

Jeff Post: Close to platinum. It’s actually the same group. It’s osmium.

Abigail: Osmium.

Jeff Post: This is an osmium nugget. Osmium is also one of the rarest metals in the earth. This is an osmium nugget from Australia. It has a little bit of iridium in it, but mostly osmium. This is the densest known metal, even more so than gold. Feel, this little nugget, how heavy that feels.

Lauren Lipuma: Wow.

Jeff Post: Isn’t that something?

Katie: Oh my goodness.

Jeff Post: I know your brain going, “That’s just a little thing. And you going, “Whoa, where did that come from?” One of the real privileges of working here is that, I spend a big part of my day sitting in front of my computer like all of us do. I’ve got all the same administrative things that you all have to do. It’s just part of being in a big organization and part of working for a living these days, email, forever.

Jeff Post: Whenever I just can’t take that part of the job anymore, I can stand up and walk down the hall. It takes me about two or three minutes to get here. I can open this room, walk in here, close the door, and you just look at these specimens. Almost every time, I’ll focus on something or just something will jump out at me. Maybe I’ve seen it before, but not for a long time, I haven’t really focused on it. Suddenly, that’s the most beautiful thing I’ve seen. You just look at it and go, “Wow, that’s just an amazing thing.” Then after you’ve done that for about five minutes, you could walk back to your desk and sit down and keep working on your computer and your emails.

Shane Hanlon: All right, that’s vault number one.

Lauren Lipuma: Vault number one.

Shane Hanlon: It’s literally behind door number one.

Nanci Bompey: The minerals.

Shane Hanlon: The minerals.

Lauren Lipuma: Right.

Nanci Bompey: Were minerals cool?

Lauren Lipuma: They are. You haven’t been to the exhibit yet, but when you go, seeing those big things that they display were these huge giant crystals that grow and these-

Nanci Bompey: I guess I’ve seen it though at other venues.

Shane Hanlon: Just because it’s not polished and pristine. We appreciate natural beauty.

Lauren Lipuma: They’re not cut.

Nanci Bompey: I know, like when they cut open the rock and it’s like…

Lauren Lipuma: Yes. Have you seen an amethyst, things like that.

Nanci Bompey: Yeah. That’s what it looks like.

Shane Hanlon: I guess that’s good with audio medium, but…

Lauren Lipuma: After that, we walked through there. Jeff took us to the gem vault, which is this small room, like I said. That’s where they keep the actual cut gemstones, and also a lot of jewelry, famous jewelry that has been donated to the collection over time.

Nanci Bompey: Is a gem just a cut stone?

Lauren Lipuma: Yes. A gem is just a mineral that has been cut and polished to be displayed.

Nanci Bompey: Did you know that?

Shane Hanlon: I’m going to say no. I was going to say yes. I probably would have figured that out, but let’s just say no.

Lauren Lipuma: The gem vault was amazing. You’ll hear Jeff describe to us some of the items they have in there, but there are just drawers and drawers of sapphires and rubies, some just by themselves, some set into jewelry. It was amazing.

Jeff Post: This is where we keep the more valuable… the gems, the jewelry pieces that are not on exhibit. We try to keep our most important or best pieces of the exhibit for the public to see, but we have a collection that is large enough that we can use it for a lot of different things. This is our gem reference collection.

Speaker 3: Oh wow.

Lauren Lipuma: Oh my gosh.

Jeff Post: Almost all of our gems have come in as donations over the years. Obviously, any mineral crystal found in the earth could potentially be faceted, be cut into a gemstone. A gem is simply a mineral crystal that a cutter has shaped and polished, and typically then might get set into a piece of jewelry.

Jeff Post: Part of what makes gems, I think, fascinating to people is they really bridge this natural history and cultural aspect of gems and minerals. You’ve got crystal that formed in nature is a whole science story there. Then, now cut by a skilled craftsperson, and now by some creative artists put a piece of jewelry, and they may be owned by somebody who’s interesting. The great thing about gems is they don’t wear out. They don’t change or diminish with time. They could get passed on from person to person. They can develop a history. There’s associations of people that go. The story that goes with the gem becomes, in many cases, as much a part of the value as the gem itself.

Jeff Post: People want a diamond that was owned by King so-and-so or Queen so-and-so, or if Lady Di wore it, or something. Those become part of the value part of the story of the gem. Our collection is really not just a collection of gems, it’s a collection of the gems and the stories of the people who gave them. Because our collection goes back now, well over a hundred years, we’ve accumulated materials from a lot of different crafts people made over different time periods.

Katie: Are these older pieces of jewelry?

Jeff Post: Those are donated to us. These probably go back to the late 1800s, maybe early 1900s.

Katie: That’s so neat. Wow, they’re beautiful.

Jeff Post: More emeralds. Not only do we have different jewelry pieces, but emeralds from different localities. For example, this is something we acquired recently. There’s a fairly new find of emeralds in last few years in Ethiopia. This is a nice stone that we got from there. You never know how long these places are going to produce, will they become important or not. Now, we have a good example from that locality and it’s one that actually could be exhibited, but also could be used for research. Come from Madagascar, again, a new locality. This is another one from Madagascar, North Carolina. We have emeralds from a lot of different localities and that is part of what makes them useful for research. There’s Russia.

Lauren Lipuma: Wow.

Katie: Wow. That’s really interesting.

Jeff Post: These are corundum, sapphires and rubies, just like beryl. Corundum is the mineral name. If they’re blue or other colors, they’re called sapphires, if they’re red they’re called ruby.

Abigail: I didn’t realize that it was just sapphires or ruby.

Lauren Lipuma: Yeah. They’re the same mineral.

Jeff Post: Sapphires a bit of iron here, but also you might get some manganese, give you a different colors, the shades of pinks to blues, to oranges for the sapphires. Chromium gives you the red color, it’s called ruby. Here’s a… This is actually a stone we just got recently. This is a ruby from Burma and it’s a star ruby.

Lauren Lipuma: Whoa. Why does it do that?

Jeff Post: It’s inclusions of another mineral, a mineral called rutile, titanium oxide. Those little rutile crystals grew inside of the corundum crystal, and they’re little needle like crystals. Because of the symmetry of the corundum crystal, the rutile crystals are forced to line up in three different directions following the symmetry. If the stones cut in the right orientation, then you end up with this star effect because it’s the light reflecting off of each of the different sets of rutiles lines in it.

Katie: Interesting.

Lauren Lipuma: That is cool.

Jeff Post: That’s one we’re hoping to get on exhibit fairly soon, too. This is one of the world’s better stars from Burma, this Burmese ruby. This is a tiara that was given to us by Marjorie Merriweather Post. In fact, this is Marjorie Merriweather Post here wearing an emerald necklace that she also gave to us, inside, on exhibit. This is one that she bought at auction in England, but probably was made, I think, in France, maybe in the middle 1800s or so. The diamonds are all set in these motifs that are on little springs. When you wear the tiara, it can kind of bounce around and catch the light and shine and shimmer and makes your tiara look a bit more exciting.

Lauren Lipuma: It does.

Jeff Post: You never know what’s going to come in the door. Again, all these have been gifts that have come in. Marjorie Merriweather Post, a lot of her things came in the 1960s really is what kicked our collection into sort of a world-renowned collection. The Hope Diamond started it off, but then she made some major gifts. In fact, one of the pieces she gave, it’s on exhibit, it’s a diamond necklace that’s got over 260 carats of diamonds in it. It was a gift by Napoleon to the Empress Marie Louise, to celebrate the birth of their son in 1811. It’s really one of the most important diamond necklaces in the world. It’s a beautiful piece. It was when Napoleon went into exile, she took this back to her family, the Habsburg family in Austria, and it was passed down through her family. Eventually purchased by Harry Winston, who sold it to Margery Merriweather Post, and in 1962, she gave it here to the Smithsonian.

Jeff Post: When she gave it to us, she presented it to us in the original box. This is the original box, the leather box that held that necklace when Napoleon gave this to Maria Louise was to celebrate, again, the birth of their son, saying, “Good job. I’ve got a son.” This is her coat of arms, her initials on here.

Katie: Oh wow.

Lauren Lipuma Oh my God. That is beautiful.

Jeff Post: Again, just the history-

Abigail: Could we see the inside? I know there’s nothing in it, but I’m just curious.

Jeff Post: You see the size of the diamonds. These are 10, 11, 12 carat diamonds. When you think this necklace was put together before diamonds were found in South Africa. There weren’t that many big diamonds around. Only very wealthy, powerful people owned diamonds at that time.

Lauren Lipuma: Where would they mined then?

Jeff Post: They were mined in Brazil and India, and mostly probably end of the India and early Brazil time was when these guys were coming out. Looking to get that many big diamonds to make a necklace like this at that time, it wasn’t until 1865 that diamonds started really coming out of South Africa in a big way. It’s makes it even more remarkable. We’ve done some studies of the diamonds in there, and even by today’s standards, many of these are considered to be the top-quality diamonds, many are what they call type 2a diamonds. These are the diamonds that have virtually no nitrogen impurities in them. They’re the most pure diamonds that we know of being found anywhere. Clearly, they were looking for the very best diamonds when they wanted to build that necklace for Napoleon.

Jeff Post: This is a necklace that has nine blue diamonds in it, and then it’s a bunch of other white diamonds. It’s a necklace that was created probably back in the early 1900s, and it was a gift to Anne Cullinan from her husband. Thomas Cullinan owned the Cullinan mine, which is the place where the largest diamond ever found came out of Africa. It’s over 3000 carats, fist size diamond. That’s the one, that for political reasons, ended up going to the King of England. It was cut, and the largest stone is in the scepter of the British Crown Jewels.

Speaker 4: The sovereign scepter, a beautifully jewel emblem of kingly power, largest of the four Stars of Africa.

Jeff Post: The family story is that Cullinan, when he bought the mine, said to his wife, “I’m going to find you a big diamond.” But the big diamond went to the King of England. He had this necklace made for her as a consolation prize, but with nine blue diamonds from his mine. Even today, that mine is still the most important source of blue diamonds in the world. Probably almost more than any other gemstone, blue diamonds sell for more per carat at auction. They’ve become so valuable. In a sense, she still got a pretty good deal.

Jeff Post: The necklace was passed down then through the family and I think, it was a great granddaughter ultimately sold it. It was a jeweler in California that bought it and then donated it here to the collection.

Jeff Post: You can see the variety of things that we do here and why I’ve been here for over 35 years. I can’t think of five minutes in that time where I was ever bored. Every day I come into work thinking, something interesting is going to happen today. So many of the great gems and jewelry pieces in the world are stuck away in safety deposit boxes and in vaults and whatever because people are afraid to wear them or because they’re being held for investment or whatever it is.

Jeff Post: Once they’re here, they now belong to all of us. What’s on exhibit can be seen by anybody free of charge. Anybody in the world can walk in and see, free of charge. The things back here, through our website researchers can study them. Nothing is lost now to the public. Again, it’s a lot of fun for the first time, somebody hands you this, the aquamarine, and you go, “All right, forever. This is now in the public arena. This is something that we all get to share.” Whereas, for the last a hundred years of this history, nobody’s seen it.

Shane Hanlon: You were there for a while, like a couple hours in total, right?

Lauren Lipuma: Yeah, about two hours.

Shane Hanlon: What was your favorite thing? What’s the favorite thing you saw?

Lauren Lipuma: Everything was amazing, but I think my favorite thing from the gem vault was, Jeff showed us a smoky quartz or citrine. It’s this very translucent mineral, a light yellow color, but it was the size of a newborn baby.

Shane Hanlon: What?

Nanci Bompey: What?

Lauren Lipuma: Yes. It was this crystal that was found in Brazil and it weighed eight pounds, and it was huge. Cut and faceted and everything.

Nanci Bompey: The baby was a gem.

Shane Hanlon: I know.

Nanci Bompey: I’m sure all babies are gems, in their parents eyes.

Shane Hanlon: Oh, look at that.

Lauren Lipuma: I would not mind a gem baby, for sure.

Shane Hanlon: Oh man. That’s all from Third Pod from the Sun.

Nanci Bompey: Thanks so much to Lauren for bringing us this story and to Jeff for sharing his work with us.

Shane Hanlon: The podcast was produced by Lauren and mixed by Kayla Surrey.

Lauren Lipuma: We’d love to hear your thoughts. Please rate and review us. You can find new episodes on your favorite podcasting app or on thirdpodfromthesun.com.

Shane Hanlon: Thanks all, and we’ll see you next time.

Thank you for sharing.