The unusual relationship between climate and pandemics

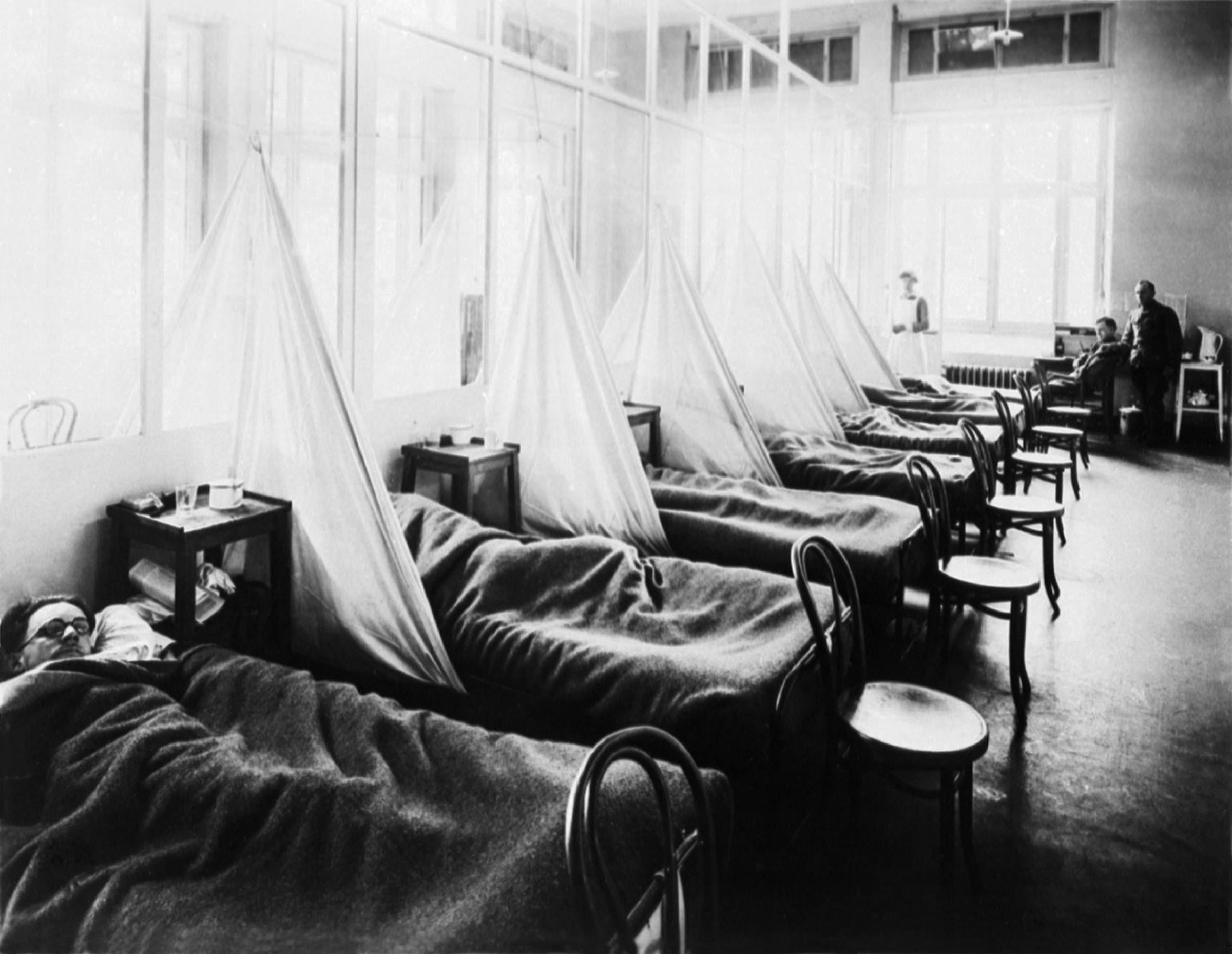

American Expeditionary Force victims of the Spanish flu at a U.S. Army Camp Hospital in Aix-les-Bains, France, in 1918. Credit: Uncredited US Army photographer; public domain.

Well-documented torrential rains and unusually cold temperatures affected the outcomes of many major battles during World War I from 1914 to 1918. Poet Mary Borden described the cold, muddy landscape of the Western Front as “the liquid grave of our armies” in her poem “The Song of the Mud” about 1916’s Battle of the Somme, during which more than one million soldiers were killed or wounded.

The bad weather also affected migratory patterns of mallard ducks, the main animal host for the H1N1 influenza virus strain responsible for the “Spanish Flu” pandemic that claimed more than 50 million lives from 1917 to 1919.

Scientists recently discovered a once-in-a-century climate anomaly brought the incessant rain and cold to Europe during the war years, increasing mortality during the war and during the flu pandemic in the years that followed.

The findings show how changes in Earth’s climate can exacerbate human conflicts and pandemics. But other research shows the reverse effect: how human pandemics can alter the environment.

A 2017 study found levels of lead pollution in the atmosphere dropped to basically zero during the infamous Black Death pandemic of 1349 to 1353. The findings showed human activity has polluted European air almost uninterruptedly for the last 2,000 years and only a devastating collapse in population and the economy reduced atmospheric pollution to natural levels.

In this episode, climate scientist and historian Alexander More describes the relationship between climate and pandemics in the context of these two seemingly unconnected pieces of research and discusses what humans can learn from pandemics of the past.

This episode was produced by and mixed by Lauren Lipuma.

Episode transcript

Lauren Lipuma: 00:09 Welcome to the American Geophysical Unions podcast about the scientists and methods behind the science. These are the stories you won’t read in a manuscript or hear in a lecture. I’m Lauren Lipuma.

Liza Lester: 00:20 And I am Liza Lester.

Lauren Lipuma: 00:21 And this is Third Pod From The Sun.

Liza Lester: 00:30 Hey Lauren.

Lauren Lipuma: 00:31 Hey Liza.

Liza Lester: 00:32 How’s the quarantine bubble?

Lauren Lipuma: 00:34 It’s a little tough these days. I must say, we’re now what, four months in?

Liza Lester: 00:38 I know. It’s like, what is time?

Lauren Lipuma: 00:40 Time doesn’t matter. I feel we’re just living the same day over and over again.

Liza Lester: 00:44 It does feel that way.

Lauren Lipuma: 00:47 But you know, Liza, I actually talked to a scientist recently who gave me a little bit of hope. I feel a little bit reassured.

Liza Lester: 00:53 I like hope.

Lauren Lipuma: 00:54 Yeah. That we will get through this and things will be okay.

Liza Lester: 00:57 Well, so who’s this person?

Lauren Lipuma: 01:00 So I talked to Alex More, who’s a scientist at the Climate Change Institute and also a professor at Long Island University. And he researches climate and pandemics.

Liza Lester: 01:11 So timely.

Lauren Lipuma: 01:12 Very timely, very timely. So Alex actually did some work recently on the Spanish Flu pandemic that happened during and after World War One.

Liza Lester: 01:21 Oh, like a hundred years ago.

Lauren Lipuma: 01:23 Yeah.

Liza Lester: 01:24 Everyone’s talking about how that was the last big mess like this, that we got ourselves into.

Lauren Lipuma: 01:28 It was, it was, it’s been a long time.

Liza Lester: 01:31 So he’s going to tell us a little bit about how we can be hopeful?

Lauren Lipuma: 01:34 Yes.

Alex More: 01:42 My name is Alexander More. I’m a professor of environmental health at Long Island University in Brooklyn. I am trained as both a historian and a scientist. What I do personally, we have multiple initiatives within the project, but what I do is look at the impact of climate change on people’s health and the economy and the impact of people on climate on the environment. Our data essentially comes from historical archeological fields, as well as scientific fields. So we use ice core data, which is the gold standard of climate science, and we have the highest resolution climate record ever produced. So I can tell you what the atmosphere looks like for any day for the last 2000 years.

Liza Lester: 02:32 So how is climate involved in the Spanish Flu in World War One?

Lauren Lipuma: 02:38 Well, actually it’s interesting. So if you go back and look at photos of World War One, or historical accounts of it, people in Europe talked about how rainy it was. It was super rainy. The trenches filled with rain. A lot of people got sick from it. And so what Alex has done in a recent study is, they went back and looked at climate data from an ice core that they from the Alps. So it recorded climate in Europe over the past several thousand years. And as Alex said, they have enough data points that they can tell you what the atmosphere looked like any day for the past 2000 years.

Liza Lester: 03:13 Wow.

Lauren Lipuma: 03:14 Yeah. And so during World War One, they found that there was actually a slight change in the climate during the period of the war. And then that may have affected how the virus, the flu virus was transmitted to people.

Liza Lester: 03:28 Oh, no, that’s so unlucky.

Lauren Lipuma: 03:30 Yeah. So, the Spanish Flu pandemic, people don’t know exactly where the virus originated from, but they think that in Europe it was transferred to humans via mallard ducks.

Liza Lester: 03:42 Ducks?

Lauren Lipuma: 03:42 Yes. I did not know that-

Liza Lester: 03:44 Your friendly neighborhood duck was the reservoir of the virus.

Lauren Lipuma: 03:48 Yes. Apparently mallard ducks are a big reservoir of flu viruses. I did not know that.

Alex More: 04:01 So from 1914 to 1918-20, we’ve noticed that [inaudible 00:04:07] circulation changed. And there was much more precipitation, much more rain, much colder weather all over Europe for six years. And what does that do to people’s health? How does that affect diseases? How does that affect populations of animals that carry those diseases? The Spanish Flu was an avian flu, H1N1. So how does that normally affect migration patterns of ducks, for example, which are the main vector of these diseases. And because this is a big data, we look at anomalies first, and this is what all climate scientists do. Really, environmental scientists look at anomalies. Anomalies are easy to spot. In this particular case, it was a hundred year anomaly. That is an anomaly that you don’t see for a hundred years. The biggest peaks, in this case sodium and chlorine, which are the components of sea salt, at the highest peaks on in a hundred year period occur between 1914 and 1920, the years of World War One.

Alex More: 05:23 And what does that mean? We all went into the books and the photographs and it’s not very difficult for World War One. And you will find, even if you just Google “rain” plus “World War One”, you will see all of the photographs and the testimonies of people that for years and years said that the war effort was hampered by rivers of mud, lakes of mud, the constant rain, the constant cold that extended into summers, even as far as Turkey, the battle of Gallipoli, the campaign at Gallipoli where the Australia and New Zealand troops suffered so much.

Alex More: 06:14 And there are poems about this one by a woman. And she called the sum, the liquid grave of our armies, because it was a field of mud. Artillery was drowned in it. People drowned in it, horses drowned in it. The trenches were full of water. People have water up to their chest. Sometimes the tunnels that were dug underneath the fields in order to reach the other side and infiltrate the other side, flooded with water. And everybody died in those tunnels as well. They developed all sorts of other diseases and pneumococcal infections, as well as trench foot, as well as all sorts of really gnarly war diseases. And this absolutely increased mortality.

Alex More: 07:14 Concurrently, you have this climate anomaly affecting wildlife. So mallard ducks, which are the main vector of H1N1, avian flu virus, reach 60% infection among juveniles, 60% of little baby ducklings have H1N1 in the fall, every fall. The main way ducks transfer the disease to other mammals, water. It’s through fecal droppings in water. The mallards I’ve been shown to be very sensitive to climate anomalies in their migration patterns. So the likelihood is that they stayed put for the entire period and they didn’t actually move. All migration studies of mallards show that the slightest change in environmental or even position in their lives affects their direction. They actually basically stay put.

Lauren Lipuma: 08:22 So where do they normally migrate to in Europe then?

Alex More: 08:27 The literature I’ve read, scientific literature, show a pattern that goes from Europe to Russia in a Northeast, Southwest back and forth pattern based on the seasons. So warmer seasons they go North, colder seasons they go South West. The patterns that we’re seeing in this case in Europe for the warriors, most likely caused the ducks to stay exactly where they were. As historians we know, and as anybody who works on a situation like a pandemic, you can take again the COVID-19 pandemic. To understand the situation, it’s important that we assume that our reality is not the product of one factor. Everything has multiple causes. So it wasn’t just the ducks. It wasn’t just the weather. It wasn’t just the historian Humphreys carefully, carefully tracked the outbreaks across the globe to understand the transmission pattern from different places, eventually to Europe and North America. And it seems to be associated with laborers hired by the allies from Asia who passed it to North America and Canada in particular, and also the United States and eventually to Europe as well.

Lauren Lipuma: 09:56 Do you know what the cause was of this climate anomaly or was it just a natural variation or was there a cause to it?

Alex More: 10:05 We did not identify an external cause except an atmospheric reorganization where the Icelandic low pressure system, which is this cold system North of Europe, which kind of sits over Iceland, became dominant over the European content for five years.

Alex More: 10:33 These atmospheric reorganizations happen and they affect people. They affect the environment, they affect what we can eat. They affect how we dress, they affect how we move, migrations, how much water is available, what animals are around. Animals follow, just like us, they follow food. And with animals come diseases. As bats have shown or civets or snakes, whoever we think was the culprit for COVID-19. And the same goes for mallard ducks and H1N, if in fact it was the mallards. Animals follow, bring their own disease environment with them in their migration and their migrations are due to the environment.

Lauren Lipuma: 11:30 During this whole story, the most surprising thing to me was the ducks.

Liza Lester: 11:33 Me too.

Lauren Lipuma: 11:34 You don’t think about ducks as being reservoirs of disease.

Liza Lester: 11:37 No. You think like pigs and chickens and bats, monkeys.

Lauren Lipuma: 11:42 Yeah.

Liza Lester: 11:42 Ducks. They seems so innocent.

Lauren Lipuma: 11:45 But you know, Alex has actually done some other work on different pandemics. And one other thing we talked about was about his work on the Black Death.

Liza Lester: 11:54 So the Black Death also had a climate component?

Lauren Lipuma: 11:57 It did a little bit, but this is actually different, whereas his work on the Spanish Flu was more how climate exacerbated the pandemic. This is how the Black Death pandemic changed the climate, and specifically changed pollution.

Liza Lester: 12:14 Oh.

Lauren Lipuma: 12:16 But in a good way. Well, in a good way, but for a bad reason. Because the Black Death was so deadly, numbers. People estimate that at least 40% of the population of Europe died in the 13 hundreds during this one particular wave of the Black Death, that industry basically stopped. And at the time people were smelting and mining metals, particularly led. And so all of that stopped. And so all the pollution that we were creating during this time just went to zero.

Alex More: 12:43 So the Black Death pandemic by death rate is the largest pandemic in recorded history that we know of, at least. What I mean by death rate is we have a death rate of 40 to 60% of Europe and Eurasia. In fact, it’s Europe and Asia, North Africa as well. We are concerned about death rates that are now with COVID going between 1% and Korea, South Korea, and 10 to 15%. And in Italy, Europe. Imagine 40. Imagine 60. It means that half of your population drops. It just disappears from a city from anywhere. So during the Black Death. Well, in the 13 hundreds for a decade between 1315 and 1325, there was a climate anomaly that we know as the great famine, which caused widespread famines and bad harvests all throughout Europe. So people were weakened by multiple famines all throughout Europe.

Alex More: 14:03 And then in 1346, there is news of a new plague, of new disease coming from the East, starts in the Black Sea and then makes its way East. Lands in Sicily in 1347. And then Genoa also, and by 1348, it’s pretty much everywhere. It reaches England in the same year and really spreads in 1349. And it kills 40 to 60% of people. It’s a version, we know for a fact, that this was a strain of plague. It’s a bacterium known as yersinia pestis, after Alexandre Yersin, who was a scientist from the Institute Pasteur of Paris, who discovered it in the late 18 hundreds in Southeast Asia. This bacterium causes very nasty infection. In fact, it causes three different kinds of infections, pneumonic or bubonic, or septicemic plague. The septicemic and pneumonic are very lethal. Whereas the bubonic creates these buboes in your neck, wherever you have lymph glands. So your neck here where you have your tonsils, under your arms and also in the groin. And these buboes become, the word is carbuncles, they become dark and black. And that’s why it’s called the Black Death. That’s where the name comes from.

Alex More: 15:38 This disease spread very quickly. It’s incubation, and because of the way that it’s transported, usually by the rats carrying fleas that are infected with it. The incubation period and its whole life cycle, which I’m not going to go into details of, really allowed it to spread very efficiently throughout pre-modern Europe, because the incubation and all of the other factors mashed travel, travel times, especially by land, but also by sea where rats love to travel on by boat. They love especially grain ships. They love grain. And grain was the staple of Europe for the diet of Europe for 2000 years. And the fleas then jumped from them to humans, often living exactly in the same quarters and humans get an infection.

Alex More: 16:37 The disease progressed throughout Europe, and you had a standstill of the economy. You had a collapse of the economy throughout Europe at this time. When you have 40 to 60% of population die, most of commercial and industrial activities cease, they stop. One of the first ones to stop was a very poorly paid activity of mining lead. So all mines in Europe stopped at this time, but particularly the ones in great Britain. And we went and documented the arrival of the plague and the interruption of the production of lead precisely to the month and day. And concurrently, we saw pollution levels of lead drop to zero for the only time in the 2000 year record, for five years. There is no other time in 2000 years of data that we have. There’s no other time when lead dropped to such low levels.

Alex More: 17:37 When you do that, you can see what the impact of historical event like a pandemic was on the atmosphere. Just like this past couple of months, we’ve seen how the coronavirus, COVID-19 pandemic has decreased the pollution worldwide. In particular, in China, in Northern Italy. And this has been captured by satellites. It’s been captured by the land based instruments, anything that we have now. But 700 years ago, there were no satellites or land based instruments. So we actually saw what we’re seeing now. So happening 700 years ago. And at the time, before COVID, we did not know that that was something that happened. This was not an established paradigm in science or literature. We didn’t really know that pandemics affected pollution, affected the atmosphere to that level. In fact, the assumption that there always was from all regulation agencies, like the environmental protection agency, the United Nations environment program, WHO, they all based their pollution standards on whatever the level was before the industrial revolution, meaning 1850 or so. And they assumed that because there was no industry, there was no pollution.

Alex More: 19:01 Guess what? That’s a lot of pollution even before industry, because we’ve been around for a long time, and we’ve been smelting toxic metals for a long time. We’ve been polluting the air for a long time with coal, with other biomass that is any wood, any coal. So what our study found was that during a pandemic, pollution levels went to undetectable level, the zero levels. To zero essentially. And why is that important? Because it’s the baseline. It’s the baseline for health. For five years the pollution fell, dropped to zero and there was no other events matching it anywhere else. So, pollution dropped for five years, not just one year, not just two years, five, during the pandemic. Just like it has during the COVID pandemic. What this did to Europe, to people, to the environment is enormous.

Alex More: 20:06 I mean, the collapse of the economy, the collapse of population brought a completely new economic system. So rents dropped and pay went up, right? Wages went up because for the first time we have labor laws, the first labor laws in Western Europe start in this period because they’re so few people who can work that they say, “You want to pay me $5 an hour? No way. 15 or nothing.” And so you have people being paid three times or four times more than they used to be paid for the same job. And they have a choice of what job they can take. Instead of having to take the old difficult jobs, dangerous jobs like mining or smelting.

Alex More: 21:01 We have, it’s really a reorganization of the entire life of the continent, not unlike what we’re experiencing today. And as a climate historian and scientist, and as a person who is very much concerned about manmade climate change and the crisis we’re experiencing, which hasn’t stopped because of the pandemic. I look at this opportunity now, I mean, I look at this crisis now as an opportunity to think, well, what can we do differently? Because this is what they did during the last great pandemic before the Spanish Flu, the Black Death, the economy was reorganized more fairly for many people. So how can we do that to reorganize our economy more fairly for the environment, and ourselves because we are part of it.

Alex More: 22:03 One thing that my environmental and historical and public health research really helps with in general, is the reassurance that I get from my information, from my data, from my evidence that we’ve overcome things like these before, and how we have overcome them. And what’s right, and what’s wrong. And you know, a lot of trial and error is being done already by our predecessors. Social distancing existed in the Spanish Flu pandemic. Its existed in the Black Death. To me, all of these stories, all of this evidence is incredibly reassuring, because I know that we’ve overcome it before. Masks were invented, the doctor plague mask that you see with the big nose, was invented for the ongoing waves of the Black Death of flake. And we are having a nationwide, global really, debate about masks today and what’s the best design. And how do we… It’s always the same story.

Liza Lester: 23:30 So this COVID situation is new to all of us alive now, but humanity has been through this before.

Lauren Lipuma: 23:36 We’ve been through before and been through it a lot and a lot worse.

Liza Lester: 23:39 Yeah. I mean, it just makes me think about how past generations just had to deal with this all the time.

Lauren Lipuma: 23:45 It must’ve been really scary. Yeah. Before antibiotics, before vaccines.

Liza Lester: 23:50 See this disease coming for you and what could you do?

Lauren Lipuma: 23:54 Yeah. Not much. Get away, pretty much. Social distancing was maybe the only thing people could do for a long time.

Liza Lester: 24:00 Returned to the old ways.

Lauren Lipuma: 24:01 Yes.

Liza Lester: 24:02 Wisdom of the past.

Lauren Lipuma: 24:04 So as much as we hate our situation now, or as much as we complain it will get better and we’ve been through it.

Lauren Lipuma: 24:12 All right, folks. That’s all from Third Pod From The Sun.

Liza Lester: 24:15 Thanks to Lauren for bringing us this story, and to Alex for sharing his work with us.

Lauren Lipuma: 24:20 This episode was produced and mixed by me.

Liza Lester: 24:22 Each of you, would love to hear your thoughts, please rate and review this podcast. And you can find new episodes of your favorite podcasting app or at ThirdPodFromTheSun.com.

Lauren Lipuma: 24:31 Thanks. And we’ll see you next time.