2-True story: Lassoing lizards (for science)

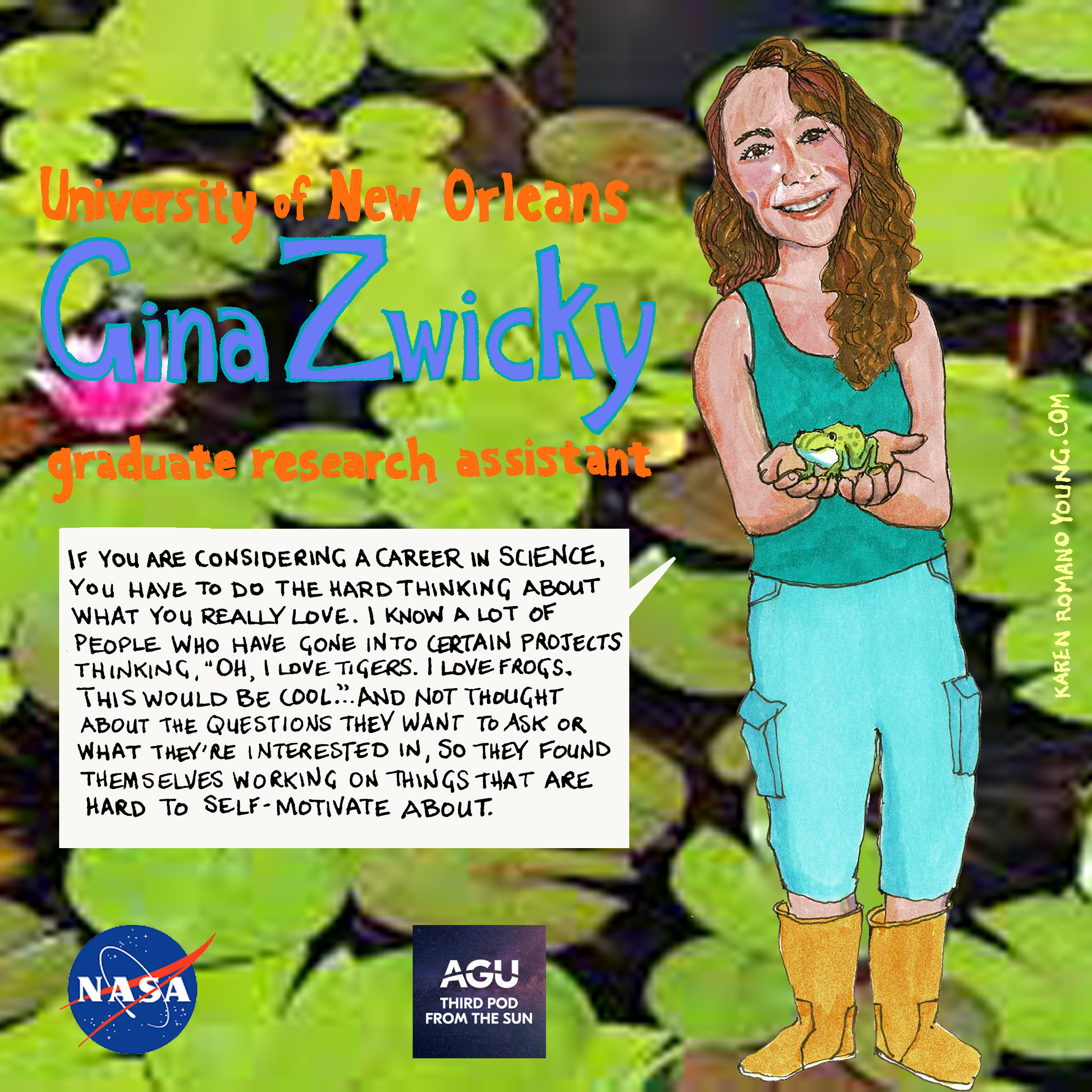

Gina Zwicky love lizards. And frogs. And turtles. Basically, all sorts of amphibians and reptiles. The love has turned into a career looking at how lizards fight off parasites and how those parasites evolve to be, well, better parasites. And when she’s not in the field or the lab, she’s wandering through New Orleans teaching folks about frogs. her about the challenges of grad school, failed experiments, and what it takes to lasso a lizard (it’s easier than you might think).

Gina Zwicky love lizards. And frogs. And turtles. Basically, all sorts of amphibians and reptiles. The love has turned into a career looking at how lizards fight off parasites and how those parasites evolve to be, well, better parasites. And when she’s not in the field or the lab, she’s wandering through New Orleans teaching folks about frogs. her about the challenges of grad school, failed experiments, and what it takes to lasso a lizard (it’s easier than you might think).

This episode was produced by Shane M Hanlon and mixed by Collin Warren. Artwork by Karen Romano Young. Interview conducted by Ashely Hamer.

Transcript

Shane Hanlon: 00:00 Hi Nanci.

Nanci Bompey: 00:01 Hey Shane.

Shane Hanlon: 00:02 What’s your favorite dinosaur?

Nanci Bompey: 00:04 I don’t have a favorite dinosaur.

Shane Hanlon: 00:06 These aren’t all going to be, what’s your favorite animal? This works though. You just don’t have a favorite dinosaur.

Nanci Bompey: 00:11 I mean, do you have a favorite dinosaur?

Shane Hanlon: 00:14 Okay, so back in the day, I was really into dinosaurs when I was five, six, seven whatever. And I would trace pictures of them on paper and then cut them out and play with them. And I remember one time I was playing with these little cutouts in a car and the window was down and one flew out onto the road and my mother, this kind woman actually pulled over and feigned looking for it. I was into dinosaurs.

Nanci Bompey: 00:42 That’s really nice of her.

Shane Hanlon: 00:43 It was very nice of her.

Nanci Bompey: 00:44 But you still haven’t answered. I mean, what’s your favorite?

Shane Hanlon: 00:47 So I don’t know. I’m more into like modern day dinosaurs these days.

Nanci Bompey: 00:52 Modern day dinosaurs?

Shane Hanlon: 00:53 Yeah. But not, I got to be clear. Not birds, lizards.

Nanci Bompey: 00:56 Right.

Shane Hanlon: 00:57 Right.

Nanci Bompey: 00:59 That’s a modern day dinosaur.

Shane Hanlon: 01:01 Lizards are modern day dinosaurs.

Nanci Bompey: 01:03 Yes.

Shane Hanlon: 01:10 Science is fascinating, but don’t just take my word for it. Join us as we hear stories from scientists for everyone. I’m Shane Hanlon.

Nanci Bompey: 01:20 And I’m Nanci Bompey.

Shane Hanlon: 01:22 And this is Third Pod from the Sun.

Shane Hanlon: 01:25 All right. So we started up at the top talking about dinosaurs, but the focus today is on lizards. More specifically, someone who studies lizards. So what do you think of lizards?

Nanci Bompey: 01:38 Lizards? I’m indifferent to lizards as well, as well as dinosaurs, but what do I think of lizards? They’re cool. They’re neat.

Shane Hanlon: 01:45 I don’t know. I think they’re cool, but we’re going to talk to someone who not only loves lizards, but is a lizard expert. Our interviewer was Ashley Hammer.

Gina Zwicky: 01:57 My name is Gina Zwicky, and I’m currently a graduate research assistant at the University of New Orleans.

Gina Zwicky: 02:03 I study the co-evolution between small lizards called anoles that live on one really, really small, specific island in the Caribbean, and their parasites in this case, specifically malaria.

Gina Zwicky: 02:15 So I look at the genetic level, how both the host and the parasite are co-evolving to keep up with each other’s defenses and attacks. So they call it a red queen dynamic based on the Alice in Wonderland red queen line about, “You can do all the running you can, just to stay in the same place.”

Gina Zwicky: 02:33 So this is sort of a shorthand for this form of evolution, where a host will evolve to be a better defender against parasites, pathogens, stuff like that. And in response to that, the parasites and pathogens will evolve to be better at infecting the host. So looking at that at the genetic level essentially.

Gina Zwicky: 02:52 Catching anoles is always a bit of a fraught task, because they’re really small and they’re really fast. So there are a couple ways you can go about it. Some people are really, really good with just the grabby hands method and as gently as possible reaching out and snapping them up.

Gina Zwicky: 03:06 But many people also use catch poles, which have a little bit of string loop at the end, which is really funny because I can never understand how the anoles don’t see you putting this little string around their neck. It looks like a fishing pole so I’ll be standing nine feet away with just an extended pole with a little piece of string on the end. And the lizard sits there like, all right, this is cool. No problem. And then you snap the pole, catch the lizard, take what samples you need and let them on their way. But they never see it coming. I don’t get it.

Ashley Hammer: 03:37 Wow. That’s amazing. You’re lassoing lizards, basically. That’s incredible. I never would’ve thought that is how you would collect a lizard. But I mean, if it works, it works. That’s great.

Gina Zwicky: 03:48 The small ones at least, I don’t envy people who have to go out and sample like monitor lizards or anything like that. So nothing quite so glamorous.

Gina Zwicky: 04:00 I do experiments called PCRs that amplify the amount of DNA I have there to work with and to sequence. So PCR being polymerase chain reaction, take a little bit of DNA, do a series of chemical reactions that turn it into a lot of DNA. And people are probably very familiar with what PCR is now with the current situation, but in case anybody is not.

Gina Zwicky: 04:21 So I work on molecular projects, meaning that again, I do a lot of PCRs and I work with DNA and reagents. So it’s really cool. It’s a lot of fun. One of the other things that is is extremely prone to contamination and a lot of getting your PCRs to work is sort of like a black box. People are very superstitious in a kind of funny way about this as well. You need to chant like a spell over your gel as it’s setting or else it’s going to all fall apart and go to whatever.

Gina Zwicky: 04:49 So I was doing my PCRs. I have about 200 lizards in my data set so I had to go through for each one and do repeated PCRs on each individual lizard blood dot to get enough data to send out. And at a certain point, I ran into serious persistent contamination in the PCRs.

Gina Zwicky: 05:08 So I was like, this is really weird because the only thing usually in my lab that will contaminate PCRs is human DNA. Because my lab mates work on monkeys and they’re closely related enough that if you breathe into your tubes or you don’t use proper sterile procedures, you can contaminate your own PCR. Because the reagents you use will think that your DNA is close enough to monkey DNA that they’ll amplify it.

Gina Zwicky: 05:31 But I’m like, all right, I’m not a lizard. I’m amplifying lizard blood. Like what is getting in here? So it could have possibly been that the pipette was spitting lizard DNA back into the different tubes.

Gina Zwicky: 05:41 But I had gone through possible troubleshooting. I had switched out all my reagents. I had switched pipettes. I had bleached, UV-treated, done everything for months and it kept happening and kept happening. And it actually delayed my degree program a full semester or more because I had to repeat all of these and they’re very time consuming.

Gina Zwicky: 06:01 I was at the end of my rope. I was so mad. I was coming in just salty, bad attitude every day, just like, all right, living the dream. But anyway, so one day, I’d had it. I come in, I’m sitting down. I’m like four PCRs away from being finished and I can’t get them to work. They’re always contaminated.

Gina Zwicky: 06:19 And I sit down at the PCR bench and a gecko scuttles out of the hood and I’m like, you! So the whole time a gecko had been living in the top compartment of the PCR bench, which has like a fan to blow air through to keep stuff from falling in your tubes, and blowing his horrid little lizard skin particles into my tubes and contaminating my PCRs for like six months.

Gina Zwicky: 06:42 I was so mad. But again, it’s one of those things that’s a really good character building experience because I just had to do it again and do it again and got really efficient with my workflow.

Ashley Hammer: 07:03 Do you have any funny or memorable stories from your research or from the field?

Gina Zwicky: 07:09 So I have a couple of really good ones that were from my first main field experience as an undergrad, the trip to Panama. That was just an absurdly cool time. The person I was working for is a really amazing scientist, Sarah Lipchitz, who now works for Loyola in Chicago, I believe.

Gina Zwicky: 07:24 But she studies jacanas, which are a species of wading bird found in Central America that have a really interesting sex role reversed breeding system, where the males will actually guard the nests, take care of the babies, and females will have a harem of males that they travel from nest to nest along their territory to check up on, hang out with.

Gina Zwicky: 07:44 But these birds are really, really, really aggressive to invaders of their territory. So the experiment that I was doing with this grad student involved making a bird robot, which was a taxidermied jacana with its wings up in a sort of aggressive position that was on a little swivel pedestal. And we would stand behind a hunting blind, like 20 yards back and pull the strings on either side and play an aggressive call on the speaker to make it seem like the bird robot was like yelling a challenge.

Gina Zwicky: 08:14 And birds would come out of nowhere and just fly and start beating this thing up. It was so funny. It was just one of the most absurd things I’ve ever like… I would stand there and just be like, this is science. This is it.

Gina Zwicky: 08:29 I think at the end of the day, if you are considering a career in science, you really have to do the hard thinking about what you really love. I know a lot of people who have gone into certain projects thinking, oh, I love tigers. I love frogs. This would be cool. And not thought that much about the questions they want to ask or what they’re actually interested in about this particular system and found themselves working on things that are hard to self-motivate about.

Gina Zwicky: 08:53 So in line with what I said before about picking your project, but it’s very, very, very important to really do the hard work of making a good project proposal and making sure it’s something you’re going to like doing before you commit to spending four or five years doing it.

Shane Hanlon: 09:17 You know, I can vouch for that. I was really interested in frogs, but I was always interested in conservation. So I think when I went to grad school, I did a bit of both sides. Interesting. Some question interesting, I guess, animal. But then I ran away from academia and now I talk to people about talking to people for a living. So I don’t know about my choices, Nanci.

Nanci Bompey: 09:40 I don’t think you can give advice. No kidding.

Shane Hanlon: 09:46 That is a great way and true way to end. So I want to thank Gina for talking with us and giving us better advice.

Nanci Bompey: 09:57 Special thanks to Ashley Hammer for conducting the interview, NASA for sponsoring this series, and to Karen Romano Young for her amazing illustration of Gina.

Shane Hanlon: 10:05 This episode was produced by me with audio engineering from Colin Warren.

Nanci Bompey: 10:09 We would love to hear your thoughts. Please rate and review this podcast and you can find new episodes in your favorite podcasting app or at thirdpodfromthesun.com.

Shane Hanlon: 10:16 Thanks all, and we’ll see you next week.

Shane Hanlon: 10:25 You can’t really hear that either, which is good. And actually since he’s back in, I’ll pop out here and close the door because…

Nanci Bompey: 10:31 Oh, he’s trying to get in the door.

Shane Hanlon: 10:32 Oh, he was right here.

Nanci Bompey: 10:33 Yeah.

Shane Hanlon: 10:33 Oh, okay. See, I didn’t hear that either. I heard him walking.

Nanci Bompey: 10:36 The door like opened.

Shane Hanlon: 10:38 Oh, so I didn’t hear that either. Yeah, he’s lovely. He’s just needy. That’s all. That’s fine though. He can understand boundaries. I’m just going to leave the dog in.