18-Ice: Ancient knowledge for modern tech

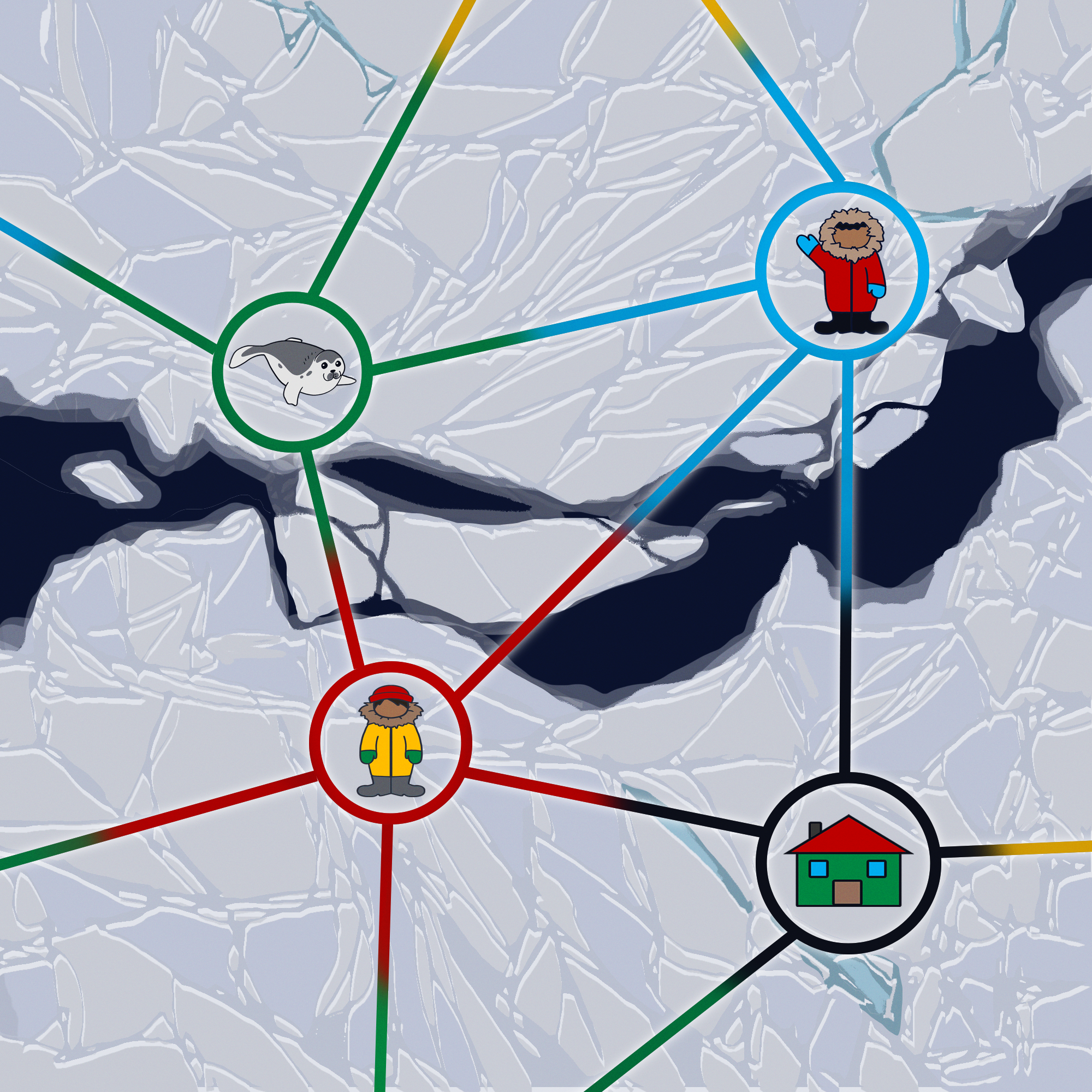

SIKU was created by Joel Heath of the Arctic Eider Foundation, and it bills itself as the Indigenous Knowledge Social Network. It allows Inuit to share knowledge about ice hazards, animal sightings, and special places — and to maintain control over that information. In this episode, we talk to Joel about why that’s so important, and how the app even works when Inuit are out on the ice, far out of range of any cell tower.

SIKU was created by Joel Heath of the Arctic Eider Foundation, and it bills itself as the Indigenous Knowledge Social Network. It allows Inuit to share knowledge about ice hazards, animal sightings, and special places — and to maintain control over that information. In this episode, we talk to Joel about why that’s so important, and how the app even works when Inuit are out on the ice, far out of range of any cell tower.

This episode was produced by Ty Burke and mixed by Collin Warren. Editing, production assistance, and illustration by Jace Steiner.

Transcript

Shane: 00:00 Hi, Vicky.

Vicky: 00:01 Hi, Shane.

Shane: 00:04 I’m just getting right into it today.

Vicky: 00:06 Oh.

Shane: 00:07 How adept are you with social media?

Vicky: 00:10 So, on a scale from Zoomer to Boomer? Or from zero to hero? Or raven to maven? What rhymes with maven?

Shane: 00:22 Raven to maven?

Vicky: 00:23 Anyway.

Shane: 00:24 Raven.

Vicky: 00:24 Raven.

Shane: 00:24 Yeah.

Vicky: 00:24 Yeah, I feel like that-

Shane: 00:26 Craven?

Vicky: 00:26 Craven?

Shane: 00:28 I don’t know.

Vicky: 00:28 Me either.

Shane: 00:29 No, I mean, just because, what’s your jam? What are you on, anything, I guess? Instagram, Twitter, MySpace? Did you have a MySpace back in the day?

Vicky: 00:36 I had a MySpace, my favorite… So, I think Instagram, although I kind of tuned completely out during the pandemic, so I heard that a lot of things have changed on Instagram, perhaps. So, I don’t know that I would still know how to use it. But Instagram… I turned AIM into a social media opportunity when AIM was a thing.

Shane: 00:56 Like AOL AIM?

Vicky: 01:01 Yeah. Oh, yeah. When that’s all there was.

Shane: 01:01 Turned into a social?

Vicky: 01:01 Yeah.

Shane: 01:01 Yeah. Back in the day when we would… I don’t know about you, but I could create really-

Vicky: 01:05 Emo?

Shane: 01:07 Emo-ey away messages.

Vicky: 01:09 We said emo at the same time. I knew that’s what you were going to say.

Shane: 01:13 Well, because it’s AIM, right? If anybody’s familiar, that’s just… Not everyone did it, but that was the place to do it.

Vicky: 01:19 Yeah. The only option was an away message. I guess it was the first Twitter, almost.

Shane: 01:23 I’m on most of the social medias.

Vicky: 01:25 All the socials.

Shane: 01:25 But I do it professionally. And so, I get home at the end of the day. Home? I walk upstairs at the end of the day. And the last thing I want to do is tweet something. Once in a while, you’ll see a picture of my dog, but that’s just about it.

Vicky: 01:37 Did Tacoma have an account on TikTok?

Shane: 01:40 I have an account on TikTok, where I would do sci-com videos with Tacoma. My dog. Yeah.

Vicky: 01:45 Oh, Tacoma wasn’t the boss.

Shane: 01:47 No, he was the talent, though.

Vicky: 01:50 Yes.

Shane: 01:50 And I loved it. It was a lot of fun, but they were… Frankly, it was too much of a blending of that personal-professional, and it took a lot of time. But what’s funny about this is, I just taught this undergraduate class a week… No, I just got back from doing some field work. All of my stuff’s public that’s public. That’s fine. And all of my students found me on TikTok, and are now following me on TikTok.

Vicky: 02:18 Oh.

Shane: 02:18 It’s fine, but things I never anticipated when making a TikTok account is whether my undergraduate students would follow me making silly science videos, in my home, with my dog.

Shane: 02:32 Science is fascinating, but don’t just take my word for it. Join us as we hear stories from scientists for everyone. I’m Shane Hanlon.

Vicky: 02:42 And I’m Vicky Thompson.

Shane: 02:43 And this is Third Pod From the Sun.

Shane: 02:48 Okay. So, what we’re getting into today is much more important than our relationships with social media, if we’re being honest. We’re talking about an indigenous-led social network that’s using modern technology to help traditional culture thrive. And so, to better explain this, we’re going to bring in producer Ty Burke. Hi, Ty.

Ty: 03:07 Hi, Shane.

Shane: 03:08 So what does that actually mean? Explain it for us?

Ty: 03:14 Well, there’s a digital platform that’s called SIKU, and it’s being used by Inuit people all across the Northern edge of North America. It’s a mobile app and a social network that allows them to share information about the sea ice with each other. The Arctic ocean, it’s frozen for most of the year and Inuit travel on top of the ice for all kinds of reasons. But one of the most important ones is to hunt and fish for food.

Vicky: 03:36 Yeah. I imagine that getting to a grocery store isn’t quite as simple as it could be for us in more metropolitan areas.

Ty: 03:44 Grocery stores are incredibly expensive in northern communities and the food sources that the people obtain on the land is still very important to the diet of the people who live in these communities and to their culture too. But climate change is having a disproportionate effect in the north. So the ice conditions are changing and wildlife migration patterns are changing too. That’s where SIKU comes in. Joel Heath of the Arctic Eider Society has worked with Inuit to develop this platform, which allows people to share up to date information about ice conditions, wildlife sightings, and various aspects of Inuit traditional culture.

Shane: 04:19 Oh wow. So there really there is an app for everything

Ty: 04:24 There is.

Vicky: 04:26 So what makes SIKU unique?

Ty: 04:29 Quite a bit. It’s been designed to work where there’s no cellular signal because there are no cell towers embedded in the sea ice.

Shane: 04:38 That’s funny. It’s like, oh, this is one of those moments where I think, of course there aren’t. Of course there wouldn’t be cell towers.

Ty: 04:45 Right, and it’s been built to address some of the specific concerns that Inuit people have about the internet and academic research too. One of the big ones is data privacy. People can choose who they share information with, so that traditional knowledge can’t be used without permission.

Vicky: 05:00 Oh, that sounds like something other social networks could maybe learn a little bit from, huh?

Ty: 05:05 It probably is. But it also doesn’t mean that all of the information that people are generating in SIKU just stays on the app either. Users have been collaborating with academic researchers to advance our knowledge of climate change and Inuit are able to provide additional context that can only come from a culture that’s been engaged with polar ecosystems for thousands of years.

Shane: 05:24 All right, well, let’s get into it.

Joel: 05:31 My name is Joel Heath. I’m the executive director of the Arctic Eider Society. We’re a small Inuit-led charity based in Sanikiluaq, Nunavut in the heart of Hudson Bay. And our main vision is around supporting thriving, Northern communities and particularly on the three pillars around community-driven research, education and environmental stewardship. And it’s really helping empower indigenous knowledge, frameworks and indigenous self determination and leading their own programs for research, monitoring and education.

Ty: 06:03 And could you explain what the SIKU platform is and how it helps achieve those aims?

Joel: 06:11 Yeah, for sure. So our programs have been really working to combine Inuit knowledge and science together. And in some cases that’s helping train people on oceanographic equipment to address their priorities or other sorts of tools. But part of the platform is like a social network, but it’s what might be considered in other context, citizen science. But it’s a really important distinction for us that it’s not about Inuit or Indigenous communities giving up their knowledge to academics.

Joel: 06:46 It’s about empowering them to manage their own programs and to have full ownership, access, and control over their own data to run their own programs. And they can decide to share that with projects as they want to, and they can make decisions about what’s more public, such as really important things like how there’s dangerous ice nearby. But they can also choose on a post-by-post basis, whether they want something like their secret berry picking spot to be hidden or masked, like you would mask a house on Airbnb and that sort of thing.

Ty: 07:18 What are some of the ways that Inuit people are using this app? What kind of information is being shared on SIKU?

Joel: 07:23 In some cases they might be more a cultural story, but in other cases, there are describing the topography or whatever the case might be that might be practical from a safety or a navigation perspective and those sorts of things. In some cases, just things like even we’re working to put inuksuit on the app where people can crowdsource the positions of inukshuks, take the picture, and maybe something happens and you lose satellite reception, but you can recognize the inukshuk based on the pictures offline and use those traditional things for navigation. But some inuksuit also even indicate things like whether there’s landlocked or sea-run fish in a lake. Some of them are more indicators of that and all those things can be important for environmental monitoring and for sustenance hunting and those sorts of things.

Ty: 08:17 And could you explain what an Inukshuk is for listeners who might not be familiar with them?

Joel: 08:23 Oh sure. Yeah. They’re piled up rocks. Some of them are just simple markers that are pointing, but the more proper Inuksuit, in some cases, they look a little bit like someone pointing, and they’re markers for navigation often, but also for marking other sorts of things that might be more about knowledge for the area. But often for navigation or as Inuit say a lot, “So the people will know we were here.”

Ty: 08:52 Are people able to use the information about ice conditions to predict and anticipate either further ice conditions or wildlife migration patterns or any other insights that someone who doesn’t have that expertise might totally miss in that language?

Joel: 09:18 For sure. Inuit, when someone shares some of those conditions on the app, they have the context to be able to interpret that and forecast. But are you asking if, do researchers have access to use that data for forecasting?

Ty: 09:34 I meant Inuit. Yeah. I meant are Inuit able to use that shared data to take that a further step or several further steps than someone like, I can go on the app and I can look at some of the things that people have posted. But I’m just wondering if you know of any examples where people are able to take something that someone posts and make judgements and predictions and choices based on that. Especially by reading into it more deeply, like this condition might result in that thing that I just wouldn’t know as a layperson.

Joel: 10:12 Yeah. I definitely know that people are using some of that information to make decisions about safety and understand the timing of things and that, but people aren’t currently posting those sorts of forecasting very much anyway. People are like, “Oh, that’s a sign, maybe the geese are coming” and you might see those sorts of comments and stuff sometimes.

Joel: 10:37 But for sure, a lot, especially in the cases of ice hazards, like the siku might crack, where if you cross it and the winds coming from the wrong direction and that’s type of crack, then you might make a decision “Okay, I’m not going to go past that, especially when the winds coming from this direction” sort of thing. And so I think it’s important that again, you’re not going to learn how to go out and understand the ice based on just the app. You need to learn from elders and from hunters and using your harpoon and to know what’s safe or not, but the app can give you more general context and help share information between hunters and so that people can use that to make their own sorts of assumptions based on their understanding assisted.

Ty: 11:40 And so can you talk a little bit about how the app puts Indigenous rights first and how you integrated that into the approach?

Joel: 11:55 Sure. That was fundamental from the beginning. When we were consulting with a lot of different groups, we worked with a lot of youth from programs like [foreign language 00:12:07] and [foreign language 00:12:07], a college program in Ottawa, but working to consult with a lot of the regional organizations, Indigenous organizations. And we knew right from the beginning that it was going to be complicated, but that in some parts were fundamental. And so prior to the problem was people were uploading everything to social media. And then if you wanted to go back and find something and mobilize it, you couldn’t. The other problem is that you’re giving up your intellectual property rights and they weren’t really a safe space for… There was kids that had posted about bowhead whale hunting in Alaska and stuff like, that were getting seriously bullied on social media for engaging in their culture and stuff like that. And so all of those sorts of things were real considerations when we designed the whole privacy policy and framework of SIKU.

Joel: 13:01 And so the first important thing was that us Arctic Eider Society were creating the platform, we’re developing the technology, but we also don’t own anything. So pretty much the opposite of what most other social networks are. We wrote ourselves out of the privacy policy so that even we can’t use information without permission and so it allows full ownership access to control over the information by the users. And so the privacy policy kind of sets it up, even if you can see something, you don’t have the right to use it. It might be helping share information about safety, but that doesn’t mean you can use it for your research just because you can create an account and you agree to these terms, but you still have to have that permission to use it and the stewardship. And then there’s other ones about respect for Indigenous knowledge frameworks and no bullying and no fake news and posting slippery mud puddles maybe is, I don’t know, it’s dangerous ice and about using your name and that sort of thing.

Joel: 14:17 So those are the safeguards that protect people overall for the whole platform, if you’re going to sign and agree. And the biggest one for the academic kind of side of things is around Indigenous governance structures. And so obviously every region has their own policies and permitting. And in Nunavut you need a letter of support from the community, often from the hunters and trappers organization. And you need to apply to the research institute for a license often to the department of environment for a license. And basically the terms say, “You have to respect what’s in place to do any research and to create a project on SIKU.” And so part of our terms mean that you can’t use our technology unless you respect the governance structures that you’re working in. And that makes it scalable as things change in different regions and flexible to different Indigenous governance structures in different regions.

Joel: 15:11 And so that was a really important part of it as well. And then the way it works for projects is if you have a project, people can join a project and then have if you have your consent forms or whether you normally have, then that’s kind of offline from SIKU, but as part of our guiding principles. And then if a member joins… Is if someone joins a project and then they’re making a post and they tag the project. So that mutual thing, they’re a member and they tag it, then they’re giving consent to steward their data. They still own, maintain their license, but they’re providing a non exclusive license to that project to use the data for their project. And so that’s a framework that allows people to share data with their community led projects or with researchers that might be working in the region and that sort of thing.

Joel: 15:59 And then the other side is on a post by post basis, you can choose the stewardship and privacy settings. And so you can separately choose the location. So you can make it people on SIKU can see it, doesn’t mean they can use it, but they can see it, or it’s masked Airbnb, or it’s fully hidden. And then there’s the privacy level, which is more about the content. So just like social media, there’s a feed on SIKU as well as the map and you can browse the feed and you can see Johnny caught a seal or harvested the seal or whatever, but you can’t dive into the details. There’s a more button that would take you to the detailed post. And so that basically can be restricted if you set the privacy between low, where anyone can dive into the details if they want to the other end of it.

Joel: 16:53 So if you can make it so that only other members of your project can see it, see the details or maximum security only, they can’t even see the post at all, unless they’re a member or in most extreme, only the admins of the project can see it. So basically it makes it pretty simple. You can hide the location or not. You can choose the level of details that you want private to other people or just to project members or project admins. And so every combination permutation of those settings is possible on a post by post basis. So you can set them in your defaults and forget about them if you want. And we’re also building in more project specific recommendations around that. Does different projects have, especially by Indigenous organizations, want to keep some things more confidential than others. And so we’re making that very flexible so that they can serve the needs for a variety of different kinds of projects and sensitive information. While at the same time, providing the same tools where people really want to reach as many people as possible, such as where the ice is dangerous.

Joel: 17:58 And I don’t think I mentioned we have 11,000 users across the North. There’s only 35,000, Inuit in the North and there’s over 11,000 users now, tens of thousands of posts and so it’s been pretty exciting to see that sort of uptake in user ship. And I think a large part of it is because it was created with Inuit for Inuit and with Cree and other groups, and that it respects those sorts of frameworks. And so we’re a couple years in now and just coming out the other side of the pandemic, hopefully. So it’s really exciting to see where this is going. And I think it’s all based on scalable architecture. We can add new wildlife species and regions. And I think there’s a framework here that can really help support indigenous communities anywhere to be able to use it for their own needs and purposes. And that privacy stewardship stuff is a key part of that.

Vicky: 19:07 So the expanse of this app is incredible.

Shane: 19:09 Yeah. I mean, I look at what I said earlier about other social media apps learning from SIKU, they’re really ahead of the game in terms of balancing privacy, which I’m sure many of us can appreciate, and community.

Vicky: 19:22 Yeah. I want to dig deeper. So just how does SIKU work on a technical level? I hope I understand this, but these areas of Canada are pretty remote. Right?

Ty: 19:33 They really are. So I made sure to ask Joel about how the app works when you’re actually out on the ice and where there would be no cellular coverage at all.

Joel: 19:42 So you can go out, you can make your post on the land. It’ll automatically get your date, time, GPS coordinates, and stuff as a part of making the post. So you just need to put in your pictures and your tags and there’s custom measurements for different species, more fields that can be added for each one. And then you save the post on the land. You can edit it before you upload it if you want. You get back to town, you have internet again, and you can upload your post. And so a lot of the architecture was really about thinking about what were the offline online connection and being able to upload stuff later and part of the training stuff is around that too. Because most people posting on social networks just make your post and you upload it right away. So, that connectivity was a key piece of the whole architecture.

Joel: 20:30 And also every time someone updates their profile picture or we add a new species or a dialect that needs to sync. So there’s a lot of the synchronization through the APIs between the online and the platforms and it being okay that they don’t sync immediately when you’re offline, but when you come back that they do. And so there’s a lot of considerations that went into that architecture. And the nice thing is we have a pretty amazing platform now and we can provide custom tools to communities and projects that want to add to that, right? And then we’re a nonprofit, it’s not for sale, but we’re working towards a sustainable vision.

Ty: 21:13 So you first came to Sanikiluaq as part of your PhD research, but you’ve been learning about Indigenous knowledge ever since. This kind of knowledge of an ecosystem is not necessarily intuitive for non-indigenous people to understand. So what are some of the things that make Indigenous knowledge distinctive and how did it figure into the development of the SIKU platform?

Joel: 21:35 So we were doing a lot of work and Indigenous knowledge about changes happening were inspiring that, but there was more specific things and an elder who passed away a couple years ago and now his name is Peter Kattuk, was out at the flow edge, hunting every day. And in our film, People of a Feather, which kind of started our charity, he talks about seeing seals, showing up the flow and that he was noticing that the contents of seals was changing from fish to shrimp. Another thing he talks about in the film is about their sinking in winter, which they didn’t used to, which he knew was an indicator for the salinity changes we were seeing from large scale hydroelectric impacts. But so they knew exactly how deep the seal sank and they knew where that fresh water layer, the interface between the different salinities was based on those seals.

Joel: 22:27 So quantitative knowledge that was there. But for the diets, for example, the typical approach was, and Inuit would share this with an academic and they’d be like, “Okay, that’s cool. And yeah, maybe that really helps reflect these large ecosystem changes that are happening in Hudson bay, especially with climate change, but you don’t write it down and it’s anecdotal it’s storytelling. So we’re going to spend five years or so and do a study to prove what you were saying.” And then five years are much money later. They’re like, “Guess what? You were right.” And the difference was is that, sure academics needs the rigorous approach, and it needs data, and it can’t be anecdotal. I get that. I got a PhD in biology and math. So my role has been how to help show that what’s being written off as anecdotal, isn’t always anecdotal and there’s quantitative data behind it. The big difference is that scientists have put a lot of value on writing everything down in excruciating detail.

Joel: 23:36 Whereas Indigenous knowledge frameworks have been based on oral history and training and around language and stuff like that. And so, one of the fundamental differences was that wasn’t being written down. And so the idea was okay, people are posting their hunting stories on social media all the time. And the picture speaks a thousand words. And what if we created a framework where people could take pictures and you could tag an animal the same ways you could tag a person and you can tag Indigenous environmental terminology, the same ways you could tag a person on Facebook or whatever. Then the data behind every one of those observations would be written down and if in the right platform, it could be mobilized to help provide equity across the table. So when Inuit are sitting down across the table from government or industry or academics that they’re empowered and not just written off as being anecdotal or storytelling.

Joel: 24:29 And so that led to our first pilot study with the SIKU app and a lot of the first features and the first testing, the whole study was inspired by Peter Kattuk’s observation about this. And then there was hundreds of posts made by Inuit hunters that were hunting seals over the next couple of years. And then Lucassie Arragutainaq, the head of the HTA and our founding board member, presented it at the Arctic Net conference, showing seasonal shifts in the diets of seals from fish to shrimp based on the data that was collected.

Joel: 25:02 And so showing the power of that picture and tagging and what’s possible through that sort of approach. And so that was pretty amazing. It was really about Inuit self-determination and their engagement in every stage of the process and really helping implement the national new strategy on research here. And we’re kind of building on that. So a big difference also, from it not just being a platform that shares what you see. That makes it kind of go to the next level about being really using Indigenous knowledge frameworks is about the language. And so there’s three main things where we have profiles or Wiki that are tagable on the platform right now that involve environment Indigenous terminology. And the first one is place names. The other one is wildlife species, which is pretty straightforward. And the third one is ice type.

Ty: 26:14 We haven’t really talked too much about climate change and changing ice conditions in the community. Have lot of, has there been a lot of change observed in the ice conditions in Eastern Hudson bay?

Joel: 26:29 Yeah, for sure. And obviously, Inuit would have more details than I do on it, but I’ve been up there for 20 years and learning a lot from folks. And even in the last decade, last five years, it’s all over the place. Sometimes it’s like a lot later freezing up and sometimes it there’s these quick freeze ups that are more episodic and it’s just a lot less predictable than it used to be. And so there’s been a lot of different changes in the ice that makes it harder for people to teach and stuff too. And to have confidence in the same way to go to some of the further distance or more obscure areas than they used to. And obviously that affects food security and all that as well. So there’s definitely been lots that’s changing. And so part of our whole approach is to allow Inuit to be leading climate change research. They’re in the North already. You don’t have to pay for the carbon footprint of their plane ticket to go back and forth throughout hunting.

Joel: 27:33 Let’s invest in Indigenous communities to lead climate change research. Cause they’re really seeing this stuff and on an ongoing basis and can help really provide that sort of data that’s going to help their own adaptation, but also help provide some of this large scale information about changes in weather and ice and that sort of thing. It really pushes the level of that, where they’re using their own Indigenous knowledge frameworks to document environmental change and climate change. And so, one thing that’s really… This is our second year now for the SIKU ice watch and it’s been all over in [foreign language 00:28:09] so that’s Inuit communities from [foreign language 00:28:12] Labrador all the way over to Tuktoyaktuk and the Inuvialuit settlement region and from James Bay up to Resolute Bay.

Joel: 28:19 At scale, for the whole North people have been posting about conditions to help with local safety, but also to help with documenting climate change. And I think we’ve had over 500 posts now this last year, and it’s going to be contributing to Nunavut weather forecast for Inuit and the weather network is going to be rebroadcasting some of this and so it’s really showing what’s possible at large scale for the whole Arctic.

Shane: 28:57 I love this idea of really helping Indigenous people in the Arctic, but we were actually chatting prior to Henry cord. And Ty, you mentioned that something like SIKU could be applicable in all sorts of settings, right?

Ty: 29:10 Yeah. I spoke with Joel about it and the technology could be applied in all kinds of different situations. The Arctic Eider Society is already beginning to explore how the app could benefit Indigenous people in other parts of the world. The same technology could be used to share information about traditional knowledge of desert ecosystems or how changing ocean conditions are impacting the location of marine wildlife.

Vicky: 29:33 That’s amazing. That’s going to make such a difference for so many communities. So when more apps or more things are built, let’s talk about it again.

Shane: 29:43 Yeah. I love that idea. We will stay tuned. And all right, folks, well that is all from Third Pod from the Sun.

Vicky: 29:53 Thanks Ty for bringing us this story and to Joel Heath for sharing his work with us.

Shane: 29:58 This podcast was produced by Ty with production assistance from Jay Steiner, audio engineering by Colin Warren.

Vicky: 30:04 AJ would love to hear your thoughts. So please rate and review this podcast and you can find new episodes in your favorite podcasting app or @thirdpodfromthesun.com.

Shane: 30:14 Thanks all. And we’ll see you next week.

Shane: 30:21 All right. So you mentioned earlier, like expensive grocery stores. I need to know how expensive are we talking here?

Ty: 30:29 I can remember going to the Northern store in Cambridge bay and in Nunavut and having to pay, I think $28 for two liters of orange juice and at the time I was living on a small ship and we were on an expedition and there was 12 or 13 of us on the ship. And we would go out to sea for about two weeks at a time and when we did the grocery shopping, before we went out, the bill would be somewhere between 25 and $30,000 usually.

Vicky: 31:02 Oh no. Wow.

Shane: 31:08 I could… I don’t even… Oh my gosh. There are no words for that. Oh, that’s rough.

Vicky: 31:12 Yeah. Oh, it’s more than rough.

Ty: 31:15 Yeah.

Vicky: 31:16 Oh my gosh.

Ty: 31:16 That’s why apps like SIKU are so important. They help bring food security to a region where, I mean, a lot of people who live there can’t afford $28 orange juice and neither can I.

Vicky: 31:28 No, me either.

Shane: 31:29 Yeah. Good. Definitely good to have that.