21-Storied careers: Scouring seas from the skies

This episode is about how satellite technology is being used to study a big chunk of the earth’s surface. Seventy percent of the earth comprises water but we know very little about it. Color sensors aboard some satellites can actually reveal a lot about phytoplankton or microalgae blooms that are linked to ocean temperatures. These tiny organisms contribute to half the photosynthesis on the planet.

This episode is about how satellite technology is being used to study a big chunk of the earth’s surface. Seventy percent of the earth comprises water but we know very little about it. Color sensors aboard some satellites can actually reveal a lot about phytoplankton or microalgae blooms that are linked to ocean temperatures. These tiny organisms contribute to half the photosynthesis on the planet.

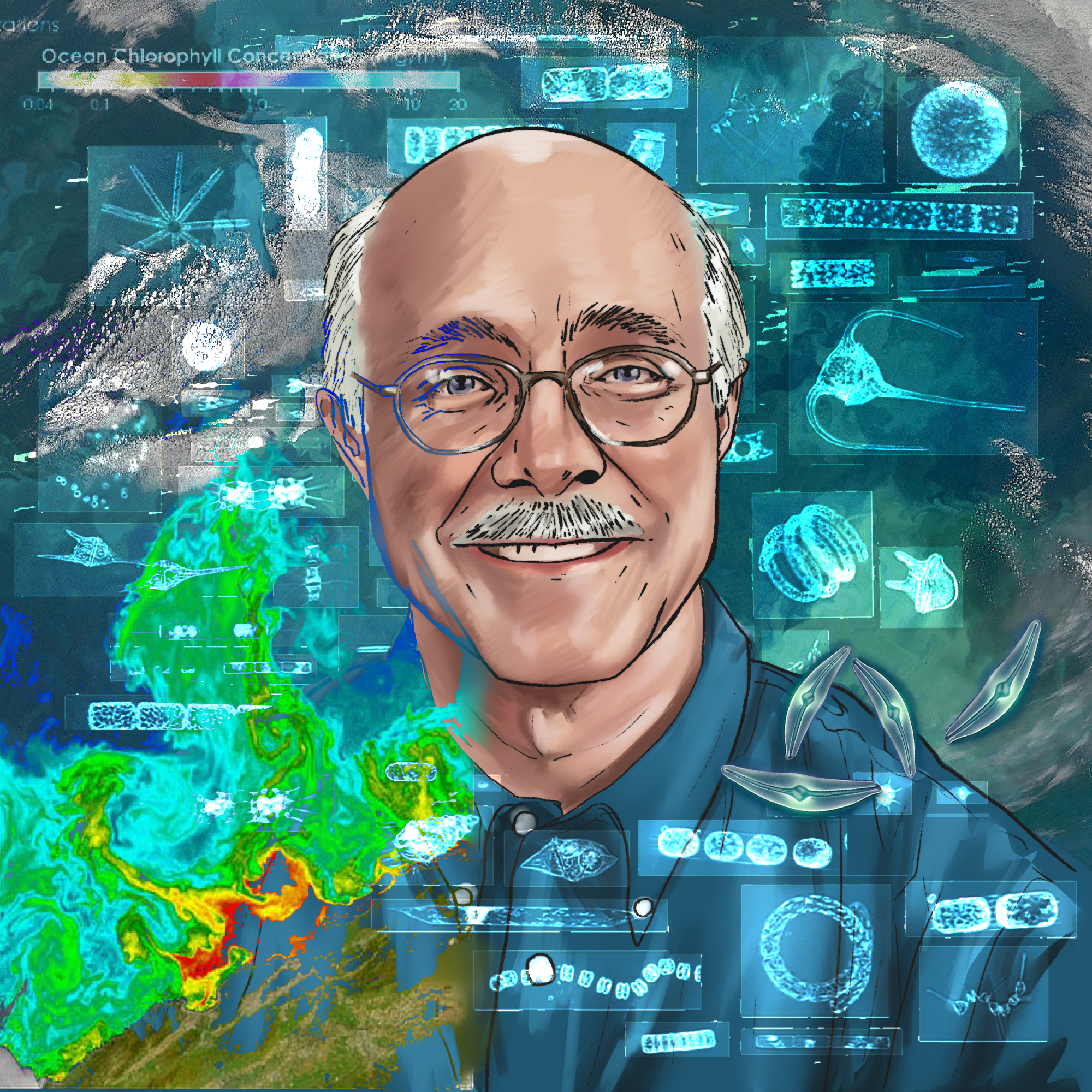

Scientist Charles McClain has done such investigations. More importantly he has traced a technological evolution too having been in this sphere since the 1970s. In this interview McClain talks about path breaking research that he became a part of in the late 1970s and how he collaborated with biologists and space scientists for this.

This episode was produced by Anupama Chandrasekaran and mixed by Collin Warren. Illustration by Jace Steiner.

Transcript

Shane Hanlon: 00:00 Hi, Vicky.

Vicky Thompson: 00:01 Hi, Shane. So-

Shane Hanlon: 00:03 So, oh. Oh, you got something?

Vicky Thompson: 00:07 Yeah. I feel like I have to do a punch buggy. Is that a thing still?

Shane Hanlon: 00:11 Punch buggy. Like when you see a Beetle?

Vicky Thompson: 00:13 Or you have to buy me a Coke.

Shane Hanlon: 00:13 Right.

Vicky Thompson: 00:14 Because we both said the same thing at the same time.

Shane Hanlon: 00:17 Oh, see-

Vicky Thompson: 00:18 Anyway, sorry.

Shane Hanlon: 00:19 It’s not a thing.

Vicky Thompson: 00:19 That’s not what I was going to ask.

Shane Hanlon: 00:20 I know what you’re talking about. All right, go ahead.

Vicky Thompson: 00:21 It is a thing. Don’t tell me it’s not a thing. Okay. So I’ve been thinking about the podcast and since I’ve just become recently involved, I was wondering how did you get into podcasting? How did this whole thing become Third Pod?

Shane Hanlon: 00:37 Yeah, that’s a great question. Yeah, So Third Pod’s been, I mean, for anyone, for our news listeners, if you go back and look at our catalog, we’ve been around for a while. We’ve been around for years. And the initial thought was that a group of folks at AGU who were all in the kind of communication space. So it was the folks in sharing science who teach communication, and our press office and our strategic communication folks, all of them.

Vicky Thompson: 01:00 People who talk a lot.

Shane Hanlon: 01:01 People who talk a lot, yeah. And who talk about science a lot.

Vicky Thompson: 01:05 Right.

Shane Hanlon: 01:05 Essentially there was this idea floated around like, “Hey, what if we start a podcast?” And I have to admit that initially I was not enthused about this idea because, I love, I mean I love this so much now. But I had some experience in other realms doing a little bit of podcasting stuff.

Vicky Thompson: 01:25 Oh, you did?

Shane Hanlon: 01:25 And more storytelling side of things. Yeah, just like a little bit. And I just wanted to be very deliberate about it.

Vicky Thompson: 01:32 Sure.

Shane Hanlon: 01:32 I didn’t want us to just start a podcast because we’re a society and we have publications and we should start a podcast.

Vicky Thompson: 01:39 Oh, right.

Shane Hanlon: 01:41 And so I wanted us to not just to summarize manuscript results or something like that, which there’s nothing wrong with that, but I wanted us to have a voice, figuratively and literally.

Vicky Thompson: 01:50 Yeah.

Shane Hanlon: 01:51 And so my involvement was with it was basically, “Hey, let’s make sure, no matter what we do, it’s fun and at times silly.”

Vicky Thompson: 01:59 Right.

Shane Hanlon: 02:00 “And that it’s not just here’s the news of the day from AGU, whatever, whatever, whatever.” Yeah.

Vicky Thompson: 02:07 Oh.

Shane Hanlon: 02:08 So that’s actually part of the reason why it was literally me on the mic and our colleague Nancy, because we were essentially voted the people who had the biggest audio presence, let’s say that generously.

Vicky Thompson: 02:24 Oh. That’s really nice.

Shane Hanlon: 02:26 Yeah. And then over the years, it’s morphed a little bit. And then, yeah, this year, literally, we’ve been pretty fortunate that it was like, “All right, let’s do something a little bit different and let’s make this thing a weekly.”

Vicky Thompson: 02:35 Yeah.

Shane Hanlon: 02:35 And make this a bigger part of my job, which I’ve been very excited by, and it gives me great joy, and I get to spend this lovely time with you, Vicky.

Vicky Thompson: 02:45 I know. It is lovely time.

Shane Hanlon: 02:45 Roughly however much we do this. But, yeah, So that’s Third Pod and me. What about you, Vicky? How did you get involved in podcasting?

Vicky Thompson: 02:54 Oh, well, like most things, completely blindly and a little bit forced. So you called me one day and said, “Hey Vicky, do you want to do a podcast? You should do a podcast.” And here we are. So thank you, Shane.

Shane Hanlon: 03:13 I didn’t, did I force?

Vicky Thompson: 03:15 No, you didn’t force me. You didn’t force me, but.

Shane Hanlon: 03:17 I did make you try out though.

Vicky Thompson: 03:19 Yeah. Well, you just said, “Hey, Vicky, I have a question for you.” And I was like, “Oh. Here we go.”

Shane Hanlon: 03:28 I was like, “Hi, Vicky. Do you want to do this?” “Yeah.” “Try out first.” “All right, great.”

Vicky Thompson: 03:31 Okay, bye.

Shane Hanlon: 03:32 All right. Well, I’m happy you’re here.

Vicky Thompson: 03:33 Yeah.

Shane Hanlon: 03:34 And this is so lovely.

Vicky Thompson: 03:34 I’m happy too. It is lovely.

Shane Hanlon: 03:41 Science is fascinating, but don’t just take my word for it. Join us as we hear stories from scientists for everyone. I’m Shane Hanlon.

Vicky Thompson: 03:51 And I’m Vicky Thompson.

Shane Hanlon: 03:52 And this is Third Pod From The Sun.

Shane Hanlon: 03:57 Well, Vicky, it might surprise you that we are not actually talking about podcasting today.

Vicky Thompson: 04:03 Absolutely shocking. Shocking.

Shane Hanlon: 04:06 I mean, we could. Who knows? Down the road maybe we’ll do an episode about science podcasting.

Vicky Thompson: 04:10 Right.

Shane Hanlon: 04:10 But for today, we’re going to talk about making the most of opportunities, though we’re going to veer away from the solid land under which my home studio is situated and wade into the oceans. And for that, we need to soar into space.

Vicky Thompson: 04:30 Okay. I have no idea what you’re talking about. What are you saying?

Shane Hanlon: 04:35 Oh, see, this is why I just don’t try to be clever. Okay. So to actually get us on track, as usual, I’m going to bring in one of our producers, Anupama Chandrasekaran. Hi Anupama.

Anupama Chandra…: 04:47 Hello Shane and Vicky. I am absolutely thrilled to clear the haze for you.

Vicky Thompson: 04:53 Yeah. So what’s Shane talking about?

Anupama Chandra…: 04:56 Well, simply put, Vicky, we are going to talk to a scientist today who has studied oceans with a bird’s eye view.

Shane Hanlon: 05:03 So not to nitpick famous last words, as I nitpick, but shouldn’t that be satellite’s eye view?

Anupama Chandra…: 05:11 Are you ever wrong, Shane? I mean, I was just speaking metaphorically. Of course, it is a satellite view, but the truth is I really never knew about this until really very recently. And apparently these satellite studies of the ocean have spanned nearly four decades.

Shane Hanlon: 05:30 Yeah. And I like this a lot because I think we definitely need more research considering that, what, 70% of the earth surface is water, yet we know so little about it. So just tell me more.

Vicky Thompson: 05:43 Yeah, go on. What can satellites tell us about the oceans?

Anupama Chandra…: 05:48 Well, I’ve just learned about all this recently, and apparently the color sensors aboard some satellites can actually reveal a lot about phytoplankton blooms that are linked to ocean temperatures. And phytoplankton, of course are micro algae. But really we can’t be dismissive of their tiny size because they actually contribute to half the photosynthesis on the planet. That’s 50%. I mean, we are talking about oxygen machines.

Shane Hanlon: 06:19 So you said you just learned about this. It’s pretty impressive how much you already know about this. Are you our interview guest today? Are we just talking to you, Anupama?

Anupama Chandra…: 06:33 Well, that was a surprise, but, well, I’m not going to shock you, Shane. Well, we actually have a real scientist, and his name is Charles McClain, who among other things, has kind of traced the technological evolution along his career. I mean, imagine if you’ve kind of been in the scientific field since the 1970s or up to the 2000s. I mean, he’s got a great story to tell us about pathbreaking research that he became part of in the late 1970s. And for this, he had to actually collaborate with biologists and space scientists.

Shane Hanlon: 07:02 Great. Let’s hear it.

Charles McClain: 07:09 Hey, my name’s Charles McClain. I have a PhD in physical oceanography from North Carolina State University. I worked for nearly 37 years at NASA Goddard Space Flight Center. And my focus was on satellite ocean color observations and the interpretation of that data. And I served as a laboratory chief towards the end of my career there. And that’s about all.

Anupama Chandra…: 07:38 To start out, I’d like to say that I was really drawn to the title of your article, An Unlikely Career in Satellite Ocean Biology or “Okay, Now What?” And it kind of lives up to its kind of title with all little details that span your scientific career from high school through 35 years at NASA. So tell us, where was the seed of this idea actually sown in your mind?

Charles McClain: 08:05 Well, I had a bachelor’s degree in physics, and when I graduated, I really wasn’t sure what I wanted to do next. The department head of the college that I graduated from had suggested I go to graduate school in physics, but I wasn’t sure that that’s what I wanted to do. So I got a position at Anaconda Wiring Cable Corporation in my hometown. And I still was wondering, “Okay, what do I want to do? I don’t want to stay in the business community.” But I ran across an article, or a special issue of Scientific American that was dedicated to oceanography and that just sort of clicked with me. And so I started applying at graduate schools in oceanography and ended up at North Carolina State and subsequently graduated and did a post doc at Naval Research Lab there in Washington DC and eventually was offered a job at NASA Goddard Space Flight Center to help with a shuttle born ocean color experiment. And that’s how it kind of progressed.

Anupama Chandra…: 09:16 For just as a primer or a background for people who are not familiar with some of the terminologies, particularly this whole idea of satellite ocean biology. Can you tell us what we are talking about here?

Charles McClain: 09:30 Okay. The basic idea, and this was demonstrated with aircraft data back in the late ’70s, is that the reflectant spectrum, the shape of the spectrum of light being reflected out of the ocean is pretty much dependent on the amount of chlorophyll in the water, especially offshore where there isn’t a lot of terrigenous material, and it’s mostly phytoplankton and chlorophyll. And there are a few other substances, but that kind of dominates the spectrum. So the more chlorophyll is in the water, the less blue light gets reflected out because chlorophyll absorbs the light. And so the idea was that you could relate that to the concentration if you measured the spectrum.

Anupama Chandra…: 10:11 What was it like to take and be part of kind of a foundational team in this space of satellite ocean biology? And what were your impressions initially?

Charles McClain: 10:25 Well, I didn’t have a clue about what ocean optics were, and I wasn’t a biologist. But shortly after I arrived at Goddard, the Coastal Zone Color Scanner was launched on Nimbus 7 Satellite, which was a proof of concept, but it had already had an experiment team associated with it, and so they were responsible for developing all the processing algorithms and demonstrating the utility of the data. And as I outlined in the paper, as part of the shuttle mission, I conducted a U2 overflight of a cruise off of Jacksonville, Florida. And in that aircraft data, we saw a very spectacular bloom along the Gulf Stream front.

Anupama Chandra…: 11:09 And when you say bloom, you’re talking about planktons over here or ocean plants or what exactly?

Charles McClain: 11:16 What happens, in this particular event, there was an upwelling of nutrients along the Gulf Stream front, and that supported a bloom of phytoplankton. Typically in the open ocean, the concentrations are really low, but when you get a source of nutrients like this, the plants just grow with rapidity, doubling times for of the order of one or two times a day. It hadn’t been observed before. And we just happened to be collecting satellite and aircraft data over the events.

Anupama Chandra…: 11:47 Wow. And how do you translate this information? What does it tell us about what’s going on, on a broader kind of global scale? How do you translate this for common people?

Charles McClain: 12:00 Well, you think about terrestrial vegetation and you take the Great Plains, for instance, all the grasses and everything. Well, basically phytoplankton are the grass of the ocean. And so it is the basis of the food web. So the plants grow, the zooplankton feed off that, and then the fish feed off the zooplankton, and it goes right on up the food chain. And that’s the importance of it. And plus it has a very important role in the global carbon cycle because the ocean takes up a lot of carbon, both through plant growth and through other mechanisms. So especially in the era where we’re concerned with global warming and CO2 concentrations in the atmosphere, phytoplankton play an important role in all of that.

Vicky Thompson: 12:47 Phytoplankton sound like climate machines.

Anupama Chandra…: 12:49 Yeah, they are, Vicky. I mean, they are basically carbon pumps, while providing oxygen, of course.

Shane Hanlon: 12:58 So Chuck was at NASA from ’78 to 2014. And I have to imagine there were a ton of changes in technology over those decades.

Anupama Chandra…: 13:08 I mean, any doubt about that? Chuck has even used an analog computer, and he really didn’t even have access to the internet when he started out.

Vicky Thompson: 13:17 Right, because the personal computer came out in the ’70s and the internet happened in the ’80s. So how did his research transform with these technological waves?

Anupama Chandra…: 13:29 If you look at discoveries and findings related to satellite ocean biology, what were kind of things that were supported because of this improvement in technology?

Charles McClain: 13:43 Well, it’s fundamental to the development of all the remote sensing that technology evolved in parallel with the science, and they fed off one another, of course. The better the technology, the more capable your sensors were and the more insights you got into what was going on into the ocean. It wasn’t just not just the biology, but it was atmospheric and terrestrial sciences as well. Prior to the satellite era, you could only get data from ships, and the sampling was very sparse. Once the satellite data became available, then you could get global views of what was going on and how those processes changed over time, the seasonality, the inter-annual variabilities on a global scale. And I think that opened a lot of eyes. We saw the spring bloom in the North Atlantic. We knew it was occurring, but the sampling really wasn’t very extensive or the a real extent of the boom. And the same in a lot of other areas of the ocean, like the Arabian Sea. The monsoon season causes a bloom every spring. And so I think it really opened a lot of eyes and a lot of opportunities for new research.

Anupama Chandra…: 14:53 So tell us a little bit about that, the collaborations that happened through the years.

Charles McClain: 14:58 Well, as you go through undergraduate school, you learn about famous scientists, and they’re almost always working alone. The Albert Einsteins and Madam Curies, they work very in a very small group. But when you get into satellite projects, it’s a team effort. Because there’s so many elements to it, you have to work together with assigned responsibilities and everybody’s relying on everybody else and it’s a real team environment. And the thing that I really appreciated was that we were all co-located. Everybody was in the same building, in the same hallways. There was a lot of interaction. People were constantly exchanging ideas.

Anupama Chandra…: 15:43 What was it like for you to understand the oceans from space? And you’ve spoken about it earlier, but what was it like for you personally to kind of understand the oceans? Because like you said, you were not a biologist, and here you were interacting with biologists as well as space researchers and satellite scientists. So could you tell us a little bit about what you were learning about climate change as were studying this data?

Charles McClain: 16:16 We have noticed changes over time on at least a 20 year scale. The same with sea surface temperatures. There are trends in that as well. And so they’re kind of connected, because the biology, the stratification of the ocean depends on temperature and if the stratification changes, then the biology changes, and so we’ve been looking at that. One of the studies that we started early on was looking at the ocean gyres, because most people look at the coastal areas because that’s where much of the action is, or the North Atlantic, or places like that. But I was curious to see if we were seeing any changes in the basin scale gyres.

Anupama Chandra…: 16:57 Which it’s a very strong ocean current, basically, right?

Charles McClain: 17:00 Yes. It’s a big circular motion basically. And it’s all driven by the surface winds. We wanted to see if these huge areas, if we could see changes there, very subtle changes. And our initial analysis we published in 2004, I think. We saw some indications that maybe the concentrations in chlorophyll were changing, decreasing in some of the basins. And I assume that that’s coincides with increasing sea surface temperatures. And let me expound on that. Why does temperature matter? The ocean’s stratified, so the warmer the water is at the surface, the harder it is to bring nutrients to the surface, because the warmer water sits on top of the colder water and the greater the difference, the harder it is to mix nutrients up to the surface. And that’s the basic concept.

Anupama Chandra…: 17:51 Yeah, no, that makes sense. And it’s actually quite visual. Anything that you’d like to add in terms of any stories that really kind of stay in your mind when you’re looking at your workspace and time? Any episodes?

Charles McClain: 18:07 Well, there are a lot of them. Starting with graduate school, with the guys that I roomed with. We did a lot of field work together. It was a learning process. We’d never done field work before. And so there were a lot of trial and error. And then, I think, I mentioned several of these in the paper. I think the day Norden told me that he was leaving North Carolina State University and going to NASA, I thought, “Oh my gosh, what am I going to do? Because how do we this?” But that was a shock.

Charles McClain: 18:39 I think, as I mentioned in the paper, each time I made this transition, I had to learn a whole new science. And fortunately, I was in a position where I had time to learn it. When I went to the Naval Research Lab, that was a totally different experience from what I had in graduate school. But I had two years to figure things out. And then when I went to NASA, what was ocean color? Well, I had to figure that out. But the system was very patient with me, and it afforded me the opportunity to come up to speed, learn, and move on from there. And I’m very grateful for that.

Charles McClain: 19:16 And well, I will add one more thing. There’s a mission scheduled to launch in early 2023 called PACE. In my mind, it’s a quantum leap in technology in terms of the sensor and its performance and the spectral coverage it provides. Well, I think it will extend the ocean color time series, the one that was started with SeaWiFS. But it will add so much new information that you’ll be able to infer a lot of new things that we haven’t been able to do before, with the hyperspectral data, like deconvolving what pigments are in the water, and maybe even inferring what species of phytoplankton are in the water. If you know the pigment composition, then you can start with that information. Then you can start seeing if species composition is changing spatially over time. Are the plants that were growing 20 years ago still growing there or are they migrating a lot of land animals and are migrating with temperature change? So it’s kind of analogous to that. We’ll find out.

Shane Hanlon: 20:33 I have a feeling that this study is going to give us a bunch of big reveals.

Vicky Thompson: 20:40 Yeah. And I don’t know whether they’re going to be good or bad. It’s certainly going to reveal a lot about warming oceans and the exponential destruction of flora and fauna.

Shane Hanlon: 20:51 Yeah, it sounds like it’s like a train wreck in the making.

Vicky Thompson: 20:55 Okay. All right. But let’s not be doomsday pundits, right? So what if this data compels us to change our ways and prevent environmental degradation?

Anupama Chandra…: 21:04 I mean, I’m going to cross my fingers for that, Vicky, because I really want to shut my eyes and not want to be part of this environmental train wreck.

Vicky Thompson: 21:14 Yeah. Hopefully we can clean up the mess we’ve created.

Shane Hanlon: 21:17 I mean, it’s about time we did, because satellites don’t lie.

Vicky Thompson: 21:23 Sorry. I feel like there’s a Sir Mix-a-Lot reference out there.

Shane Hanlon: 21:29 Oh man. That will not happen on this podcast. So instead, that is all from Third Pod From The Sun.

Vicky Thompson: 21:34 Okay. Thanks so much, Anupama, for bringing us this story, and to Chuck for sharing his work with us.

Anupama Chandra…: 21:39 Thank you.

Vicky Thompson: 21:40 This episode was produced by Anupama with audio engineering from Colin Warren. Artwork by Jay Steiner.

Vicky Thompson: 21:45 We’d love to hear your thoughts on the podcast. Rate and review us. You can find new episodes on your favorite podcasting app or at thirdpodfromthesun.com.

Shane Hanlon: 21:54 Thanks all, and we’ll see you next week.

Shane Hanlon: 22:01 Maybe this will make it to the stinger so we can-

Anupama Chandra…: 22:02 You guys. Are you guys Gen Zs? What are you guys? Gen Zs? Millennials?

Vicky Thompson: 22:05 I think I’m the very oldest Millennial, technically.

Shane Hanlon: 22:09 We are elder Millennials, let’s say. No, first computer we had in our house was ’93, ’92. It was like an Apple G something, one of the first standalone Apples they had with the green screens?

Vicky Thompson: 22:29 With just DOS.

Shane Hanlon: 22:29 Yeah.

Vicky Thompson: 22:29 Was DOS on Apple? I meant DOS.

Shane Hanlon: 22:30 No, it was it Apple’s whatever. Their OS. But, yeah, that was the first one we had. So we are of the we didn’t have computers at one point generation.

Anupama Chandra…: 22:40 Well, you probably had a computer way before even I’ve had. I think I had my first computer in ’96 or something, like way way-

Shane Hanlon: 22:47 The first PC we had, I remember, was ’95 because my brother graduated high school and he went to college for computer programming. And my parents bought him a Gateway.

Anupama Chandra…: 22:58 Oh wow.

Vicky Thompson: 23:00 Big deal.

Anupama Chandra…: 23:00 And it was like for Christmas, and it didn’t work, and literally, well, it wouldn’t register the mouse or the keyboard or something. And he spent the first morning ripping this brand new computer apart that my parents spent at the time, thousands of dollars. This is a really expensive thing. And my parents were freaking out. He’s like, “Don’t worry, I know what I’m doing.” He fixed it. He got it all working.

Excellent podcast review of color satellite oceanography and Chuck’s career. His contributions have been immense despite the modesty of his responses. Congratulations to Chuck and the podcast team.