32-Spaceship Earth: A love of space through a son’s telescope

Dorian Janney is a science communicator for NASA asking the big question: how do we make science accessible? Sparked into Earth Space Science through her son’s curiosity with space, we talk to Dorian on how her journey as an educator and life-long learner led to working on NASA’s Global Precipitation Measurement Mission as a Senior Outreach Specialist, and how citizen scientists from around the world are providing important work for researchers through the GLOBE Observer Project.

Dorian Janney is a science communicator for NASA asking the big question: how do we make science accessible? Sparked into Earth Space Science through her son’s curiosity with space, we talk to Dorian on how her journey as an educator and life-long learner led to working on NASA’s Global Precipitation Measurement Mission as a Senior Outreach Specialist, and how citizen scientists from around the world are providing important work for researchers through the GLOBE Observer Project.Shane Hanlon: 00:00 Hi, Vicky.

Vicky Thompson: 00:01 Hi, Shane.

Shane Hanlon: 00:01 Happy New Year.

Vicky Thompson: 00:03 Happy New Year. 2023.

Shane Hanlon: 00:06 Oh, I know. It’s very exciting. Yeah, I almost stepped up and said happy… Oh, I was going to say, happy new season. Yeah, we’re still in the middle of our final series and our season one because I’m great at scheduling, but it is in fact-

Vicky Thompson: 00:20 It worked out okay.

Shane Hanlon: 00:22 … a new year, and this episode will be the first in the new year, but-

Vicky Thompson: 00:26 Great.

Shane Hanlon: 00:27 … beyond that. I know recently, if folks have been listening along, if you haven’t, you should, that we talked about doing outreach science or otherwise. But today, I was wondering what’s been your most or one of the most rewarding outreach or community service or any type of experience that you’ve had?

Vicky Thompson: 00:49 Yeah. I think when we first talked about outreach, I talked about creating programming at an art fair that I had been involved with for many years-

Shane Hanlon: 00:58 Sure.

Vicky Thompson: 00:58 … in the local area. And I think within that, I always found the most rewarding thing to be when I scheduled children’s programming. We used to do specifically every year I would help organize this big kids’ mural, which was essentially, because we were in an empty… The whole thing was like an empty building, and you fill it with art for six weeks. And then, you take it out, and it’s an empty building again. So, essentially, we would find a blank wall or a blank office somewhere in this empty building and just give kids paint and let them go to town.

Shane Hanlon: 01:34 That’s awesome.

Vicky Thompson: 01:34 We first tried to have an actual mural with like, “Here’s a minion, here’s another character-

Shane Hanlon: 01:41 From Direction?

Vicky Thompson: 01:41 … call them in.” And no, no, no, no. It’s much more fun just to give little kids paint and let them go wild on a blank wall because it’s so outrageous to their little lines. And that was just always the most rewarding because it was just great to share. And because they really, really thought they were making… and they were, I shouldn’t say it that way.

Shane Hanlon: 02:07 You thought they were making art?

Vicky Thompson: 02:07 They were really-

Shane Hanlon: 02:07 They’re making arts.

Vicky Thompson: 02:08 They are making art. Exactly.

Shane Hanlon: 02:08 It’s like psychic-

Vicky Thompson: 02:08 It’s just like-

Shane Hanlon: 02:08 … graffiti.

Vicky Thompson: 02:12 Exactly. They loved everything that they were making. They felt so free and excited to make it, and we’re sharing it with each other and-

Shane Hanlon: 02:19 Oh.

Vicky Thompson: 02:19 … in the space. And it was, yeah, really fun.

Shane Hanlon: 02:21 That’s lovely.

Vicky Thompson: 02:24 Yeah. Yeah. That’s mine. That’s me.

Shane Hanlon: 02:25 Yeah.

Vicky Thompson: 02:26 That’s my favorite thing.

Shane Hanlon: 02:29 I used to pre-print… pre-pandemic, pandemic…

Vicky Thompson: 02:32 Prandemic. No, that’s good.

Shane Hanlon: 02:32 Prandemic.

Vicky Thompson: 02:38 Prandemic.

Shane Hanlon: 02:38 I had a side gig at the National Zoo here in DC-

Vicky Thompson: 02:42 Great.

Shane Hanlon: 02:43 … where I have talked about parts of this before. But yeah, I did this thing called Snore and Roar. And reminder for folks, if you haven’t been listening along, basically we would take groups of mostly families and do behind-the-scene tours with them, and then we would sleep overnight in the zoo in tents on one of the greens that’s right outside of-

Vicky Thompson: 03:05 Amazing.

Shane Hanlon: 03:06 … the big cats, so where mostly the lions were. And it was such a… I said about it, it’s a wild experience. You’re hearing sirens in the middle of the night and wolves and the lions roaring in and all of that stuff. But from the rewarding standpoint, I was just a host. I wasn’t one of the, let’s say, animal experts, but we would go and talk to keepers. And I love the zoo. I mean, no qualms about that. But seeing these kids, one, they’re camping overnight in a zoo, a lot of these kids had never camped before, full stop.

Vicky Thompson: 03:42 Right.

Shane Hanlon: 03:42 And so, that was just a whole new experience for them, and that was really fun and everything else and seeing that happen, but these kids would just light up. You’d get behind the scenes and you’d be… I don’t know, a few feet away from this giant lion or a maned wolf or a zebra or whatever it might be, and exposure that you can’t get in the normal experience. That’s still great.

04:11 And they would just… The kids, who probably just didn’t care, and their parents dragged them into it, they would just light up. And I don’t know if these are forever transformative experiences, but holy cow, I can… I mean, I’m already… I was a biologist and all of that, but I can imagine if I would’ve had that sort of experience at that young of an age, I mean, I would just have that much more of a love for it. So yeah, just seeing these mostly kids just have at least, maybe not their lives change, but definitely maybe a week or a few months change-

Vicky Thompson: 04:42 Yeah, that’s what I was going to say.

Shane Hanlon: 04:42 … in a very developmental-

Vicky Thompson: 04:42 It makes super sense.

Shane Hanlon: 04:44 … period of their life. Super cool. Super rewarding. I would love to be a part of that again. Maybe someday, I will.

Vicky Thompson: 04:52 Yeah, no, that’s… I love that both of our things relate to children. I think that’s the biggest thing, right? It’s so fun to help kids see new things or see new things, new passions, find new passions or new excitements for themselves.

Shane Hanlon: 05:07 Yeah. Well, and they’re so impressionable too. And so hopefully, by getting positive impressions, that weighs out potentially some of the other stuff, which… whatever that might be.

Vicky Thompson: 05:17 Yeah. Although I worry about them when you said a few feet from a giant lion-

Shane Hanlon: 05:22 Totally safe, Vicky.

Vicky Thompson: 05:24 … about what impression-

Shane Hanlon: 05:26 No.

Vicky Thompson: 05:27 … if something bad were to happen.

Shane Hanlon: 05:29 No physical impressions, no children were harmed in this experience.

05:39 Science is fascinating, but don’t just take my word for it. Join us as we hear stories from scientists or everyone. I’m Shane Hanlon.

Vicky Thompson: 05:48 And I’m Vicky Thompson.

Shane Hanlon: 05:50 And this is Third Pod from the Sun.

05:55 So today, we’re talking about outreach. And no, again, I can’t stress this enough, no children were harmed in any of our outreach experience.

Vicky Thompson: 06:06 Well, I’ll just say that-

Shane Hanlon: 06:06 It would be [inaudible 00:06:07].

Vicky Thompson: 06:06 … a few more times before the end of the episode.

Shane Hanlon: 06:10 I know, right? Just like to get all the qualifiers out there. But we are talking outreach because that’s literally today’s guest’s job. And I know that many of the folks we talk to on the podcast are researchers or other folks who put outreach in their job as part of it. They try to include some component of science, communication, or outreach into their work, but that’s a job of who we actually have today.

Vicky Thompson: 06:36 That’s really exciting. I can’t wait to hear what they do.

Shane Hanlon: 06:40 Yeah, it’s going to be really great. And so, we will get into it. Our interviewer was Ashley Hamer.

Dorian Janney: 06:49 My name is Dorian Janney. I work for NASA at Goddard Space Flight Center. I work for a contractor called ADNET, and I am the Senior Education and Outreach Specialist for the Global Precipitation Measurement mission, which is this really amazing satellite that NASA launched in 2014. It’s an international collaboration. We are working closely with Japan, as well as several other countries have satellites that are in our constellation. I serve as an interpreter or as a narrator to help people who don’t really know about the mission, better understand why and how we are, in this case, measuring precipitation from space.

07:41 The other hat I wear for NASA is that I work with a program that’s called the GLOBE Program, and it’s been operating since 1994. And it’s basically a way to empower and enable any citizen to just basically use their smartphone technology so that they can collect data and make observations about our environment all over the world from the ground. And then, we can compare and contrast those data with our satellite data from above.

Ashley Hamer: 08:14 Wow, that’s great. Basically, you’re the connection between NASA and the public. You’re helping to translate everything that they’re doing and get the public involved in science also.

Dorian Janney: 08:28 That is such a perfect way of putting it, the kind of interconnective tissue, if you will, between the amazing things that are being done. And then, how can I translate that? How can I put that into something that is not only understandable but also your average person would say, “Oh, wow. That’s cool. And now, I understand why that’s important, how that helps us as a society.”

Ashley Hamer: 08:55 Yeah, that’s great. How did you start working for NASA? What happened there?

Dorian Janney: 09:02 That’s really a neat question. I started off in early childhood special education and absolutely loved it. But after many years passed, I got into metacognition, thinking about thinking, and into some different types of learning and ways of thinking that pushed me to move and work with older students.

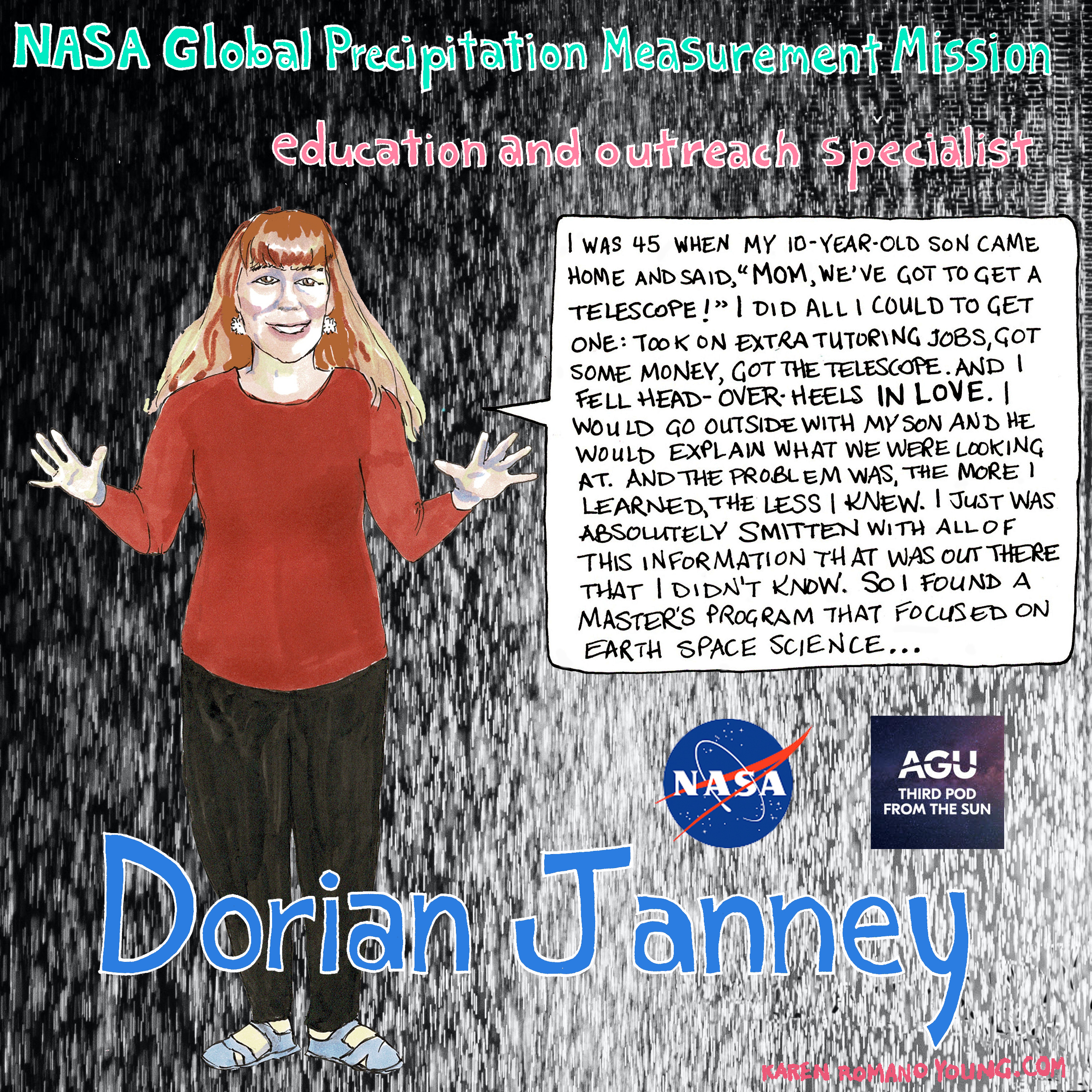

09:28 Then, when I was teaching fourth and fifth grade, I have a son who now is a scientist at NOAA. He was in fifth grade, and he came home from a summer camp and he said, “Mom, we got to get a telescope.” Well, when your 10-year-old says, “Mom, we got to get a telescope,” you do what you can to get a telescope. So, I took on some extra tutoring jobs, got some money, we got a telescope. And what happened was I fell head-over-heels in love. I would go outside with him, and he would explain to me what we were looking at.

09:58 And the problem was the more I learned, the less I knew. And I just was absolutely just smitten with all of this information that was out there that I didn’t know. So, I found a master’s program at Johns Hopkins University that focused on Earth space science, and I joined a cohort and I got a second master’s in Earth space science. So then at that time I started teaching middle school and high school. I went straight to just teaching science, and I would go in the summers and I would work for NASA.

10:32 And in 2011, they asked me would I consider supporting the satellite mission that would launch in 2014? Now, it’s been nine years, and we’ve been doing great things with the satellite missions.

Ashley Hamer: 10:46 Oh, that’s such an inspiring story that you came to science through your 10-year-old son. Can I ask how old were you when that happened?

Dorian Janney: 10:55 Sure. I would imagine at that point I was probably about 45. And so, like I said, I went back to school and there I was. My kids would sit around the table doing their homework, and there was mom working on her second masters, doing my homework too. I even went on and did some doctoral work, but it just got to be awfully expensive and trying to work full-time and do that.

11:16 Also, at that point in time, I had gotten the job at NASA and for what I was doing, I didn’t have to have that doctorate, but it was cool. I was studying. My focus was studying what 11-year-olds have as their working mental models for distances in the universe.

11:36 And I came about that because in working with all of my middle school students and teaching them about space, I realized that there were a lot of misconceptions in that some of them thought we could get to the moon in two hours, and others thought it would take us 20 years. And it just hit me that in order for them to really understand distances in the universe, I had to get a feel for what was it like to be in an 11-year-old’s head. And that was really exciting to do that research and do some studies on that.

Ashley Hamer: 12:10 Oh, that’s so cool. It sounds like your son was one source of inspiration. Do you have any other sources of inspiration that got you to where you are?

Dorian Janney: 12:19 My mom was just great and always supporting any kind of strange hobby I would have. She let me bring home the guinea pigs and have all the different animals. And I always had bug and butterfly and rock collections. So, I would be out in my hiking boots collecting bugs, and I remember being teased by a couple of the kids in my neighborhood that that’s what I was into.

12:45 And I can remember going home and kind of crying and my mom just rubbing my forehead and saying, “You know, sweetie, that’s okay. It’s okay that you’re different. You’re interested in different things.” So just from an early age, I’ve always been interested in the outdoors, and I’ve always wondered why. I’m sure I drove my parents and my teachers nuts because I never just accepted a straight answer. Well, I want to know why. Well, how?

13:14 And I find I’m still that way. If I’m out walking in the woods, I’ll look at a tree and notice that maybe it’s got a certain fungus growing around it. And then, I wonder, “Oh, wow. Is this part of the fungal network that I’ve been learning about?” And everything just then tastes like more, I need to keep learning more.

Ashley Hamer: 13:38 What is your favorite place to talk about science?

Dorian Janney: 13:42 Wow. Wow. Gosh, I do love it. We do a lot of different kinds of tabling. So I will go to the Science and Engineering Festival and have a table and Earth Day at Union Station. I will go to American Geophysical Union, to a variety of different conferences. What I love to do is to engage and inspire and teach people like, “Well, here’s what’s going on with this,” or have them ask the questions and guide them to the understanding. It’s like how do I continue to inspire and motivate and communicate this information that I find so interesting?

14:27 And something that came from that. Now, one of the main focuses that I have with the work that I’m doing with the GLOBE Program is getting lifelong learners, people like me who are age 55 and older, getting them involved in the GLOBE Program and in collecting this data, and then understanding how and why NASA studies our home planet. And that’s a really exciting charge that I would not have considered before as being necessarily an audience that I was so focused on reaching.

Ashley Hamer: 15:02 Yeah, that’s great. And who better to talk to than people who are just like you, you know how they think, you know what they need to hear to become excited. Well, on that note, do you have any funny or memorable stories from your career? From any of these projects? From anything?

Dorian Janney: 15:23 Sure. I guess I have these funny stories that things that will happen all the time, particularly when I’m interacting with the public. One time, I was telling some kids about the fact that water isn’t a cycle and that we use the same water again and again. And that probably a long, long time ago that water was dinosaur pee. So, a little girl looks up at me and she goes, “Oh, so dinosaurs are the ones who made water.” I was like, “Oh, no. Now, I’ve created a super misconception.”

16:00 I thought that was just a funny thing, and I’ve always got to be aware of that as a science communicator. It is to get a feel for what people’s preconceptions are regarding any kind of natural phenomena. And then, if it’s a different conception, an alternate conception, than what we know as scientists, then helping to scaffold that, to bridge that gap, and then also to listen to make sure I haven’t created more confusion in the meantime.

Ashley Hamer: 16:32 It sounded like, from what you were saying about the 10-year-olds or 10- and 11-year-olds, that those preconceptions can be all over the place. How do you figure out what someone’s preconceptions are?

Dorian Janney: 16:43 That’s such a good question. And I guess really two ways. One is interacting with the general public of all ages, because I feel like without that interaction, you really are in a vacuum. But then, the other is noting what those kind of questions were and things that they wonder about. And then learning, learning, learning.

17:04 Right now, I’m teaching a course to lifelong learners on climate change and how NASA uses satellite technology and airborne missions to help us look at vital signs, to help us understand climate change. And so, I’m always reviewing not just misconceptions about climate change, but let’s say I’d ask me a question about, well, how is it that we know what the atmosphere was like 11,700 years ago? And so, I will go to multiple sources to be able to then come back and give information.

17:39 So, it’s really a two-fold combination of knowing how to go and get valid, reliable information from American Geophysical Union, from NASA, from NOAA. There’s a great many sources that when you go to have reliable and valid data, but then also finding a way that I can listen to what it is they’re asking so that I’m answering the question that they’re asking versus creating more confusion.

18:10 I think a big challenge is the fact that we have now such a sophisticated way of understanding things, i.e., the technology. And we have such sophisticated understandings in science that it is very challenging sometimes to then communicate that to the general public, to politicians, to voters, and helping your average person to understand how that technology does yield in valid understandings.

18:47 And another thing that I also think is kind of a challenge. When I had begun teaching, Pluto was a planet, and then during my teaching, Pluto was demoted. And I had a colleague come in to me and say, “I’m so sorry. I heard about Pluto.” And I remember saying to her, “Oh, this is so exciting. This is how science works. Pluto doesn’t care. Pluto’s still there. Pluto still is recognized as a super important component of our solar system.” But what’s happened is that we’ve broadened our understanding, utilizing more sophisticated technology, and that’s just forced us then to need to come up with a new conceptual scheme.

19:32 So, I’m saying all this to say that some of the challenges we have, as scientists and science communicators, are that when we are trying to help the public understand things, we have to find ways to make it understandable, and we also have to help with this narrative that, yes, sometimes is going to change. It doesn’t mean that the facts are going to change. It doesn’t mean that nothing can be believed because everything’s going to change. So, it’s a complicated and challenging road to walk in helping people to know that, yes, there are facts in science. And yes, those facts will change, but that doesn’t mean that things aren’t real, that we don’t know what we’re talking about.

Ashley Hamer: 20:20 Oh, that’s great advice. What personal achievement are you most proud of?

Dorian Janney: 20:36 I am super stoked that I work for NASA. There’s truly not a day when I don’t just wake up and feel satisfied that I am in a situation where I can continue to learn because I love to learn, and I’m in a very, very… I would say, an environment that values and appreciates questioning and dialogue and discourse, and really working to understand how our natural world works. And then, also to make that information available to decision makers.

21:19 I would have to say that just being in this situation where I can reach out to people who are, say, using the data from the Global Precipitation Measurement mission. I’ll give an example. There’s a really fascinating civil and environmental professor named Faisal Hossain at the University of Washington, and he is using our data to help banana farmers and wheat farmers in Pakistan, India, Bangladesh, who normally would be taking water from the very, very valuable freshwater rivers. They would take the water from those freshwater rivers to irrigate their fields.

21:59 But over the last 20 years, that freshwater has become less available and so important to so many other people. And so, helping them to come up with a behavior change where Faisal Hossain figured out a way and worked with the government that these farmers could get just burner cell phones, where they would just get a text telling them water or irrigate. And with irrigate, they go and open up the rivers or the other one says don’t irrigate, and it tells them that it will rain. That way, they are not using those valuable freshwater resources, and they’re still getting their crop, but the people then have more freshwater resources to use.

22:43 So, that’s the sort of thing that I feel is just a super achievement, is being able to reach out to these people, to hear what they’re doing and then say, “Wow, how cool is that?” That this sort of use of technology is being done, understanding that these farmers are generally not in a position to understand how to access this satellite data, but ensuring that they have it in a way that is useful and easily accessible to them. And then, that’s also helping to make our society better. So that, I would say, is a big achievement.

Ashley Hamer: 23:23 And then finally, I just want to give you a chance to plug anything you want, especially the GLOBE Project. How can people get involved with that?

Dorian Janney: 23:30 Oh, excellent. Well, what you can do is if you have a smartphone, go to the App Store and find an app called GLOBE, G-L-O-B-E, Observer. And that’s a free app. It is NASA sponsored. We also are supported by NOAA, the Department of State, and the National Science Foundation.

23:52 So, get out there, try the app out, run around the neighborhood. Basically, with that, you’re looking at clouds, you’re looking for potential mosquito-breeding habitats, measuring tree height, and looking at land cover. And you’re doing all of this simply with your smartphone. All the directions are in the app. You don’t need any fancy equipment. You just need for each of these about five, maybe 10 minutes. And it’s a great way of being connected with your environment.

24:23 Not only that, but it gets you looking at saying, “Huh, who else was looking at potential mosquito habitats around the world today? And what did they find?” And you’re part of this group of people who are collecting this information and find it interesting. And also, if you do collect it and get interested, we have a couple of campaigns, one called Trees Around the GLOBE, another one called GLOBE Mission Mosquito. And we have monthly webinars. We just share some of the ways in which these data are being used by different people to make the Earth a better place and to better understand our home planet.

Shane Hanlon: 25:09 Vicky?

Vicky Thompson: 25:10 Yeah?

Shane Hanlon: 25:14 How are you making our planet a better place?

Vicky Thompson: 25:17 How am I making it a better place?

Shane Hanlon: 25:19 Yeah, we’re holding ourselves accountable in the year of 2023.

Vicky Thompson: 25:24 Oh, gosh. Okay. Well, so this podcast, right?

Shane Hanlon: 25:28 Oh my gosh, Vicky, you took my answer.

Vicky Thompson: 25:30 Darn. Okay. But the other thing was, I was going to circle back to something we discussed during fall meeting, and I’m really going to start composting.

Shane Hanlon: 25:42 Oh, good.

Vicky Thompson: 25:42 Yeah.

Shane Hanlon: 25:42 Yeah.

Vicky Thompson: 25:42 That’s just a very small thing, but-

Shane Hanlon: 25:44 Hey, you know what? Little things count.

Vicky Thompson: 25:47 Yeah.

Shane Hanlon: 25:47 Yeah. I don’t have a good answer for this. I’m just going to try to be a better person, so here we are.

Vicky Thompson: 25:52 Oh.

Shane Hanlon: 25:55 Oh. And I really appreciate, on a serious note, the work that folks like Dorian do to not only communicate science, but to really get folks engaged with it. Because again, going back to the purpose of the podcast, if the more folks understand it and can relate to it and are interested in it, then I think that’s just a great thing. So, thank you again to Dorian for sharing her work with us. And with that, that’s all from Third Pod from The Sun.

Vicky Thompson: 26:21 Special thanks to Ashley Hamer for conducting the interview and to NASA for sponsoring this series.

Shane Hanlon: 26:27 This episode was produced by Jason Rodriguez and me, with audio engineering from Collin Warren, and artwork by Karen Romano Young.

Vicky Thompson: 26:35 We’d love to hear your thoughts. Please rate and review us, and you can find new episodes in your favorite podcasting app or at thirdpodfromthesun.com.

Shane Hanlon: 26:44 Thanks, all, and we’ll see you next week.

26:50 All right. Do you have an answer to this?

Vicky Thompson: 26:53 Mm-hmm.

Shane Hanlon: 26:53 Ooh.

Vicky Thompson: 26:54 Yeah. Yeah. I mean, it’s not that interesting. That was rude to myself. It is interesting. It’s so interesting.

Shane Hanlon: 27:04 Vicky, you shouldn’t be self-deprecating. You should be like, “Yeah-

Vicky Thompson: 27:06 I am very-

Shane Hanlon: 27:07 … it’s amazing.”

Vicky Thompson: 27:08 So, that’s just part of my personality, and it’s always weird when I encounter somebody that doesn’t understand that, and they’re like, “Oh no, I really feel like you’re great.” And then, I’m like, “Oh, no, no, no. I don’t really believe that I’m-

Shane Hanlon: 27:18 Right. Exactly. I don’t believe-

Vicky Thompson: 27:20 … as silly as I-”

Shane Hanlon: 27:20 … these words are coming out of my mouth. I’m actually quite awesome.

Vicky Thompson: 27:22 Yeah. Just the thing I say.

Shane Hanlon: 27:23 Yeah.

Vicky Thompson: 27:24 Yeah, I really like myself.

Shane Hanlon: 27:26 Yeah. Whoa. Oh, goodness. See, this is good. We’re starting off 2023 with some good self-affirmation.

Vicky Thompson: 27:31 Yeah, you got it.

Shane Hanlon: 27:32 I like me.

Vicky Thompson: 27:33 I like me.