One giant leap: For beating the odds and troubleshooting telescopes

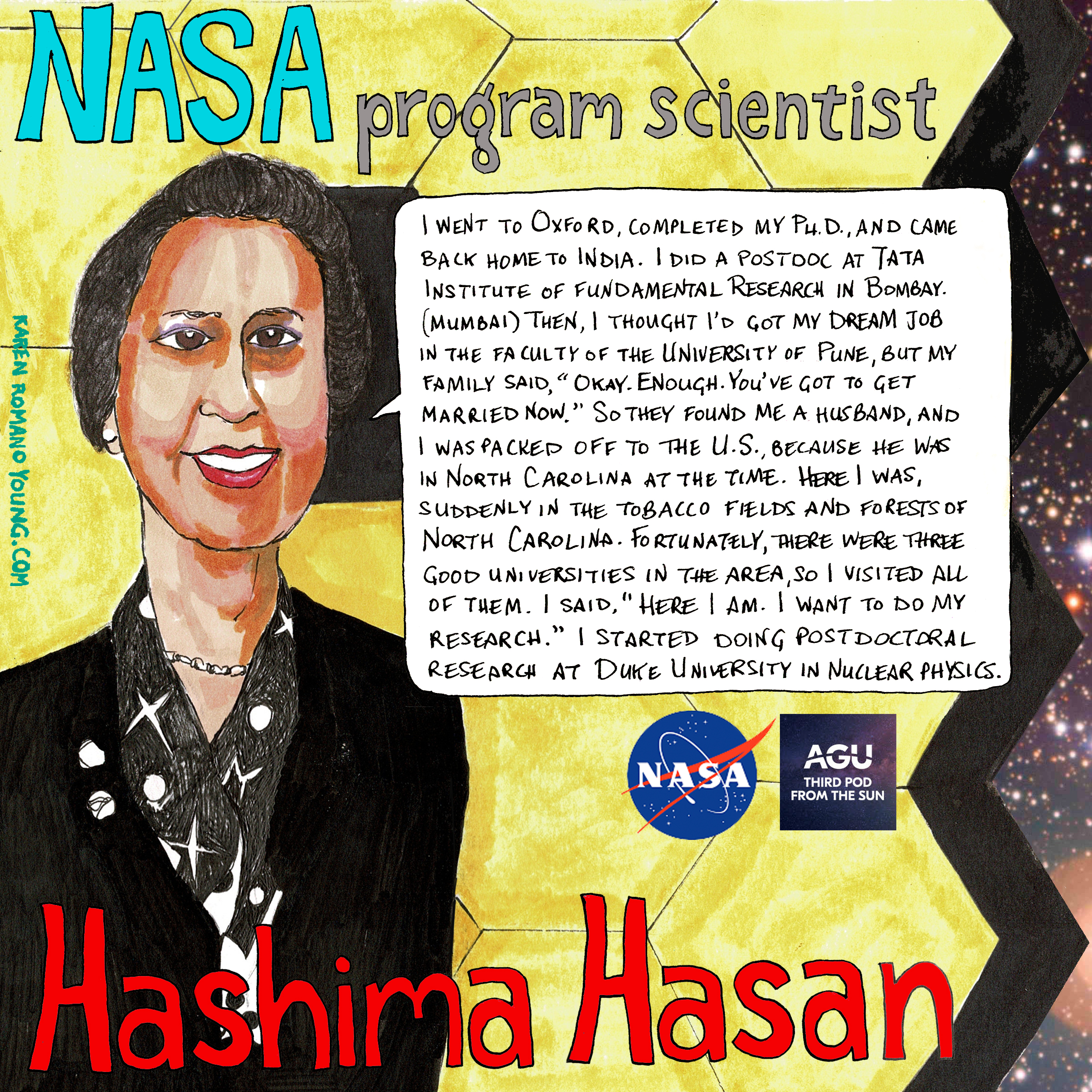

Hashima Hasan is the program scientist for NASA’s James Webb, IXPE, and NuSTAR telescopes, helping to bring those missions from cradle to grave. Hashima followed the space race closely growing up in India, which inspired her to navigate into the sciences from a world where girls were told that they couldn’t. She talked with us about writing simulation software for Hubble, troubleshooting its first blurry images, and spending 9/11 on lockdown in DC while choosing where the James Webb Space Telescope would one day be built.

Hashima Hasan is the program scientist for NASA’s James Webb, IXPE, and NuSTAR telescopes, helping to bring those missions from cradle to grave. Hashima followed the space race closely growing up in India, which inspired her to navigate into the sciences from a world where girls were told that they couldn’t. She talked with us about writing simulation software for Hubble, troubleshooting its first blurry images, and spending 9/11 on lockdown in DC while choosing where the James Webb Space Telescope would one day be built.

This episode was produced by Zoe Swiss and Shane M Hanlon, and mixed by Collin Warren. Artwork by Karen Romano Young. Interview conducted by Jason Rodriguez.

Transcript:

Shane Hanlon: 00:00 Hi, Vicky.

Vicky Thompson: 00:01 Hi, Shane.

Shane Hanlon: 00:02 What’s the coolest thing you’ve ever won? Talking material object as a door prize, a raffle, something like that.

Vicky Thompson: 00:10 Like a contest?

Shane Hanlon: 00:12 Yeah, sure.

Vicky Thompson: 00:13 You know, I feel like I win a lot of stuff.

Shane Hanlon: 00:14 Oh. All you do is win, win, win no matter what?

Vicky Thompson: 00:19 Yeah. But I don’t feel like, I can’t think of anything. I don’t think anything’s ever been the coolest. I won a Kindle once.

Shane Hanlon: 00:29 Oh, that’s neat.

Vicky Thompson: 00:30 That was neat. But I already had a Kindle. So I won it and went up to get it. And by the time I came back to my group of people, my husband had already given it away.

Shane Hanlon: 00:44 You told me this story.

Vicky Thompson: 00:48 Yeah. He was like, “She already has one. She doesn’t need that. Who wants that?”

Shane Hanlon: 00:51 I mean, that’s just very kind of him. He’s just, you’re always winning and he’s always giving. You know?

Vicky Thompson: 00:58 Yeah, I guess we make a good pair. It’s pretty rude, actually. Kind in one way, rude in another way in. That’s okay.

Shane Hanlon: 01:03 Because he didn’t ask you.

Vicky Thompson: 01:06 Yeah. He doesn’t like when I tell rude stories about him on podcast.

Shane Hanlon: 01:11 Sorry. I think what’s funny is when I think about, I’m not like that. I don’t really know. I can count on one hand, on very few fingers, how many times I’ve won a thing. But I actually think in the same type of event where you got your Kindle, I recently, in a raffle, won a telescope.

Vicky Thompson: 01:41 Yeah.

Shane Hanlon: 01:42 And I was complaining at this event, that’s been going on for many years, and I had never won anything. And that’s not how drawings work. I understand how probabilities were.

Vicky Thompson: 01:42 It’s random. Yeah.

Shane Hanlon: 01:54 It’s got to be my year, and so I’d just given up. And I was literally, it’s just so funny because I wasn’t even expecting anything. Of course, you don’t expect something like that. And I was walking back to my table and it was one of the last ones of the night. And I was, “Okay.” So I pull the ticket out and I read through it. And then it was the numbers, and I don’t know, I mouthed something to myself, probably something vulgar, if I’m being honest.

02:23 Wait, what? And I read it again.

Vicky Thompson: 02:25 What?

Shane Hanlon: 02:25 And I think I literally just held my ticket up in the air. I was like, “That’s me.”

Vicky Thompson: 02:30 The raffle gods heard you.

Shane Hanlon: 02:34 The raffle gods heard me. Yeah. So, yeah, now I have a telescope that my partner did not give away.

Vicky Thompson: 02:43 Oh. Well, that’s nice.

Shane Hanlon: 02:45 Yeah. That is very nice of her. So one for her, zero for your husband.

Vicky Thompson: 02:51 Yeah. Yeah.

Shane Hanlon: 02:57 Science is fascinating, but don’t just take my word for it. Join us as we hear stories from scientists for everyone. I’m Shane Hanlon.

Vicky Thompson: 02:57 And I’m Vicky Thompson.

Shane Hanlon: 03:08 And this is Third Pod From The Sun.

03:14 All right. So pretty straightforward today. We are talking telescopes, but more than that. But specifically someone who’s worked on and is working on telescopes for NASA, that are a little bit bigger in, well, scope, I guess.

Vicky Thompson: 03:35 Oh.

Shane Hanlon: 03:35 You’re reading ahead to the silly things of writing in this script. But yes, bigger in scope and bigger full stop than my small, but honestly, very exciting telescope.

Vicky Thompson: 03:35 Yes.

Shane Hanlon: 03:46 My very exciting raffle prize. Do you all have a telescope? Have you ever owned a telescope?

Vicky Thompson: 03:53 So I don’t have a telescope. I’ve asked. My parents have a telescope.

Shane Hanlon: 03:53 Okay.

Vicky Thompson: 03:57 But it kind of just lives in the corner of the guest room. I don’t feel like we use it very much.

Shane Hanlon: 04:04 Does the guest room have a window?

Vicky Thompson: 04:07 Well, yes, there is that. That’s helpful.

Shane Hanlon: 04:09 I ask that because I have not used mine yet.

Vicky Thompson: 04:09 Okay.

Shane Hanlon: 04:12 It’s literally sitting right beside me in my basement studio, because I just haven’t figured out where it’s going to live yet. I have an idea, but it just hasn’t made it there. So yes, it is together, but it is sitting right beside me.

04:29 But maybe this episode, maybe this interview, will be my motivation to start getting some use out of it.

Vicky Thompson: 04:35 Oh, that will be nice.

Shane Hanlon: 04:36 Yeah. Yeah. So, let’s get into it. Our interviewer was Jason Rodriguez.

Hashima Hasan: 04:48 I am Hashima Hasan. I work at NASA headquarters as a program scientist for a number of astrophysics mission. I’m the Deputy Program Scientist for the James Webb Space Telescope, and the Program Scientist for the IXPE and NuSTAR Telescopes, as well as a partnership with Keck Observatory. I’m also Executive Secretary of the Astrophysics subcommittee, and I’m the Education and Outreach Lead for Astrophysics.

05:19 Each role, as you can imagine, is a little different. So for a program scientist, what we say is we take a mission really from cradle to grave. So at the time that it’s conceived, we are really responsible for what the science objectives of the mission will be. So we work with the scientific community to define the science questions. And then, once the mission becomes real, we have to write solicitations for the science instruments, which will go on onto the missions.

05:54 Or if it’s a compete admission, like IXPE or NuSTAR, what we call explorers, then we write the solicitation for the explorer program and select missions for that. And then we have to, once it’s operational, we have to get the best science out of it. So that’s the Program Scientist duty.

06:15 As Executive Secretary of the Astrophysics advisory committee, that’s a way that the federal government gets advice from the public, is through committees which are formed under the Federal Advisory Committee Act, which are called FACA committees. So I have to set up the agendas and the meetings and all that good stuff, and get advice from the community.

06:42 And then of course, education and outreach. I think that’s self-explanatory. We have education programs in astrophysics as well. And then outreach as well, generally to go out and speak about our science programs to schools, to public and so on.

06:58 No two days look alike. I may imagine I’m going to do X, Y, and Z today, but it may just turn out to be different. So-

Jason Rodriguez: 07:08 What drew you to science to begin with?

Hashima Hasan: 07:11 Well with science, actually, I would say right from my childhood, I was just fascinated with how nature worked. And I was born in India and I was raised there, and this was very soon after India got independence from the British. So the country’s very underdeveloped and there was practically no electricity. And the skies used to be dark and clear. And at night, I would just stare at them and my mother would tell me stories about the stars and the moon.

07:42 And then in the monsoon, everything came to life. There were lots of little new creatures. I still remember there’s a little red bug, which looked like velvet and it used to move across. And I think they’ve got extinct. Then there’d be fireflies at night, and there’d be all kinds of new plants coming out, butterflies. I mean, it used to be so fascinating.

08:06 And as I grew older in school, I got a little more… We were actually taught formal science in school, and I would take flowers and dissect them and see what they were made of. We used to collect pupas, see them turn into butterflies.

08:21 And then when space race first started, when Sputnik was launched, I was think five or six years old, and my grandmother took all of us into the backyard to see Sputnik go across the night, actually, early morning sky. I still remember that. I was just so fascinated with that.

08:41 And then the first man in space, Yuri Gagarin, visited my city, Lucknow. My mother took all of us to meet him at a VIP reception. And then, we really followed the space race very excitedly. Every morning, we’d look in the newspapers, what’s happened today?

09:00 And then the first woman in space, Valentina Tereshkova, visited New Delhi. My mother took us to visit her. So my mother was really very much behind this, encouraging this interest in science. And when man landed on the moon, I just was so fascinated. Gosh, wouldn’t it be exciting to work at NASA?

09:22 And I had some role models, in the sense that I knew that an uncle was a scientist, but I didn’t actually meet him so much. And in school, we used to read about Marie Curie. So I used to be very fascinated about Marie Curie, and I read everything I could about her. And I felt that if she can do science, surely I can too. Though, there aren’t too many women there, I think generally in science, leave alone in India.

09:54 We had just got independence, and political leaders and our family, they were very much that you are the new generation. You will build this country. And to build the country, you have to be scientists. And at that time, in my innocence of childhood, I didn’t think that, I’m a girl, I won’t be able to do science. And we were told that everyone has equal rights, so I would have same rights as my brothers, and that was very empowering.

10:29 I wanted to do science in school. At that time, it was a girl’s school. It was run by Roman Catholic Irish nuns. At the time that I joined the school, the nuns didn’t believe in teaching science to the girls, except botany and home science. But I was lucky that when I reached the ninth grade, we had a new head mistress, and this nun had just come back from America and she had this revolutionary idea that girls can do science. So she introduced science in school.

11:01 So a small group of us, we said we were interested. So we were tested and we were allowed to do science. And the real challenge was to find women teachers to teach science. So we used to have a sort of string of, if one came, another left. But somehow or another, we did finished our School Leaving exam, which in those days was conducted by the University of Cambridge in England.

11:28 Then I went to the university in Lucknow, and that was the first time I went into a co-educational environment. And I had to go to the university because there were no women’s colleges at that time in Lucknow which taught mathematics in college, in the medium of English. There was one in Hindi medium, but not in English medium.

11:50 So I went to Lucknow University. They recognized that there weren’t too many young women doing science. And so to encourage us, I would say, they actually had set aside a common room in the mathematics department, which was called the girls’ room. So in between classes, all of us would just go and sit in the girls’ room because we didn’t want to mix with the boys. It was just not in our culture. But that enabled us to at least study science. And in our classroom, they would make us, all the girls used to sit in the first row so the boys wouldn’t harass us.

12:34 So I finished my Bachelor’s, and then typically that was about the time when girls were supposed to get married. But I was fortunate, again, that my parents gave me freedom. They said, “If you want to get married, we’ll find a husband for you. Otherwise…” I said, “No, I want to go and do Master’s.”

12:51 So I went to Aligarh University, where my cousin had just done physics, and she thought I should go there. So I did my Master’s there. When I picked up courage to apply to the University of Oxford, got admission there. So it took me about a year to get a scholarship. Went to Oxford, completed my PhD. I came back to India. I did a post-Doc at Tata Institute for Fundamental Research in Bombay.

13:16 Then I thought I’d got my dream job in the faculty of University of Poona. But by that time, my family said, “Okay, enough. You got to get married now.” So they found me a husband, and I was packed off to the US because he was in North Carolina at that time.

13:44 And so, here I was suddenly in the tobacco fields and forest of North Carolina. 1979, that’s what it was, I can tell you, in Raleigh. But fortunately, there were three good universities in the area. So I visited all of them. I said, “Here I am. I want to do my research.” Just finished my… You know, it had been three years since my PhD in Oxford.

14:07 So, you know, I learned later that this is a very typical American thing, where there’s something new, you give it out free. So I said, I’m here to work for free, because on my visa, I can’t accept money from you. So all three, they were quite happy to get a free Oxford PhD. They said, “Sure.”

14:27 So I started doing post-doctoral research at Duke University in Nuclear Physics. By that time, visa status changed and I was able to get fellowship at, it was a national research council fellowship, at the US EPA, to study air pollution in Denver, Colorado. Because in those days, a big brown cloud used to settle over Denver. So they wanted me to understand which pollutants caused visibility degradation there.

15:00 So I did that. Then in the meantime, I gave birth to a baby, and that’s another story. And I can tell you sometime about that one, about trying to get better [inaudible 00:15:11] for that.

15:11 Then we went back to India again for visa reasons. We went back for a couple of years. Had another baby there, and then came back and found myself in Baltimore. So, I started looking around in Baltimore.

15:25 By that time, they were kind of winding up the Nuclear Physics in the Physics department. They had a physics and astronomy, and they said, “You know, we have this new institute, Space Telescope Science Institute. We want to see if you can do something there.” So I went there and they said, “We are looking for someone who knows optics, to write the simulation software for the Hubble Space Telescope and its sciences instruments.” This was 1989. No, ’85. 1985.

15:54 So I said, “Yeah, sure, I’ll write it.” I thought, well, I can do nuclear, the arrogance of a nuclear physicist. I said, “I can do that. Surely I can write the software for this, whatever this Hubble is.”

16:08 So I joined the institute. I wrote the software. And when Hubble was launched, it turned out that that software was instrumental in analyzing, because we saw the images were aberrated. I mean, a lot of kids your age don’t even know that a Hubble has an aberrated mirror, but it does. It’s not perfect.

16:31 And so my job became to analyze those images and to keep the Hubble in what they call best focus. I was made the telescope scientist, and so I worked on Hubble till we did the first servicing mission. And after that, I just thought, I want to do something different.

16:47 One thing was that the science atmosphere for women was a little hard at Space Telescope at that time, and so I just wanted to go somewhere else. And this opportunity came up at NASA headquarters. So I joined in 1994, as a visiting senior scientist. And then, few years later, they hired me as a civil servant. So, there you go.

Jason Rodriguez: 17:16 Wow. Wow. That’s such a journey.

Vicky Thompson: 17:27 Wow. That’s such an incredible journey.

Shane Hanlon: 17:30 I know. So I was listening in on these two. I was running sound and tech for this interview when Jason was conducting it. And I listen in obviously, but mostly it’s for, I’m kind of usually zoned out and listening from a technical perspective to make sure the audio sounds good.

17:50 But I do remember, I think I looked up from what I was doing and I was just so enraptured by everything that she did to get where she is today.

Vicky Thompson: 18:00 Yeah. And I imagine that even beyond what she shared, there were probably times when things didn’t go quite as planned.

Hashima Hasan: 18:08 When I wrote the optical software for Hubble Space Telescope, the idea was that I write the software, Hubble will launch, we’ll have these beautiful images and we’ll be analyzing them. And that’s how I’ll be doing, and life will be good.

18:24 But when Hubble launched, it was not what I had expected. And really, life took a different turn after that. So I wouldn’t say that it failed, but it certainly caused a very big turn in my plans. So rather than analyzing Hubble images and doing science, here I was trying to fix Hubble.

18:54 When the images from Hubble came down, they were blurred. They were not the clear images you are seeing. And so we said, why are they blurred? So we started analyzing them and looking at the optics. And we realized that there’s something wrong with the mirror.

19:18 The edges of the mirror have been shaven off like a hair’s breath more than they should have. So the rays, which were coming from the edges of the mirror, converged at a different point from the rays that came from the rest of the mirror. So instead of you getting a point, you were getting one point here, one point there, and they made kind of a blurry thing in between. So that was the problem.

19:46 And then, when NASA started doing its investigation, went back to the company which had made the mirror and looked at everything. It turned out it was a really very bizarre error. What had happened was, when they were shaving the mirror, they used to test it with an instrument, which was like a little telescope, and the mirror in that instrument had a little kind of a black paint on the tube, so it would be protected. Turned out that a little chip from the paint had come off, which is just near the mirror. So instead of the light reflecting off the mirror, it reflected off that little chip.

20:32 And so there was just that little hair’s breath of a difference was made. So when they were measuring the mirror as they were grinding it, they grounded a little bit too much.

Jason Rodriguez: 20:44 Oh, wow.

Hashima Hasan: 20:46 And actually, NASA had sanctioned two mirrors. The other one was made at Kodak, and that mirror was perfect. And it’s sitting in the Air and Space Museum in Washington, DC. You can go and see the perfect mirror there.

Shane Hanlon: 21:05 Vicky, we live in the DC area. Have you been to Air and Space? Have you seen this mirror?

Vicky Thompson: 21:12 So I’ve been to Air and Space, but I can’t tell you whether I’ve seen the mirror or not. Last time I went, maybe the only time I went, I was chasing a two-year-old around.

Shane Hanlon: 21:21 Oh.

Vicky Thompson: 21:22 So, I don’t think I actually saw anything except for her.

Shane Hanlon: 21:27 Yeah. I think, I was going to say common misconception, I have no idea what other people think, but I do think a misconception for folks who don’t live in our area, who know that we have all these museums, is that we all go constantly. And I’m sure some of us do, but I think a lot of us don’t.

Vicky Thompson: 21:45 Right.

Shane Hanlon: 21:45 For no reason. That’s an amazing resource. I’ve been to Air and Space a handful of times. I’ve been to, there’s two. There’s one downtown DC, then there’s one out in Virginia that has one of the space shuttles and SR-71, and some bigger stuff.

22:00 Both very cool. And I’m sure I have seen this mirror. But yeah, I can’t off the top of my head recollect it.

Vicky Thompson: 22:10 Right.

Shane Hanlon: 22:12 But also, I think the downtown one just had a big renovation, and I have been wanting to go back. So I will pay special attention next time.

22:23 But as you might imagine, so mirrors or otherwise, Hashima has had a lot to be proud of. So we just asked her about it.

Hashima Hasan: 22:34 One that always comes to my mind is, JWST, when we started off, it was called NGST, Next Generation Space Telescopes. I was the program scientist for NGST at that time. This was around between ’99 to around 2001.

22:56 We had these very intense negotiations with a European space agency on one of the instruments, called the mid-infrared instruments, where the Europeans were going to build half of it, and the Americans were going to be, well, NASA was going to be the other part. And then once those negotiations had been decided, what NASA would do, I was told by my management, “You have to find out, find which NASA center will manage this instrument.”

23:27 So I had to write to the directors of the three NASA centers, which had the right capabilities, Goddard, Ames and JPL, and invite proposals from them. And we were reviewing those proposals on 9/11, September 11th, 2001. And it was, I think, around 10:00 AM when the building manager came and he said, the building in which we were holding the review, it was in DC but it wasn’t headquarters. It was close to it.

24:03 And he said, “I have to interrupt you,” because at that time, there were just rumors. He said, “This plane has hit and there’s fire in the White House.” I think that plane, which had fallen in the Pentagon, people could see the fire. They couldn’t really tell where it was. Some thought it came from the White House, and they said, “The Metro has been closed and everything has been closed.”

24:27 And so my boss, she sort of suspended the meeting. Because we had people who had come from California to make presentations, she said, “Go get to your hotel reservations back because you can’t fly back. The airports are close.” So they did that. And then she said, and she called headquarters and she said, “You know, there’s complete chaos in the streets. Nobody can go anywhere. So let’s just continue the review.”

24:56 So there I was, responsible for the review. We continued the review, and in between, in the intervals, I was trying to call my husband. I was trying to call my children and not getting any response. But we completed the review. So I felt really proud about that.

25:16 And so whenever I see the images coming from the mid-infrared instrument and the science coming from that, I think of that day. And I feel really proud of the role that I played in that instrument.

Jason Rodriguez: 25:31 Yeah. Working under that intense pressure and under those circumstances.

Hashima Hasan: 25:37 And then when I went out after the review, it was 2:00 PM. They had just opened the Metro. It was really surreal because it was really a beautiful day. It was a beautiful autumn day. The sky was blue, the weather was just perfect. And there wasn’t a soul on the streets in DC, except police and barriers. And I’d never seen DC like that.

26:04 I went into the Metro. I was standing alone on the platform. It was so scary. And I thought, first train that comes, I’m going to jump on. I don’t care where it’s going. So first train came, Silver Spring, I just jumped on it. Got off at Silver Spring, and by that time I was able to contact my husband, when I got out at Silver Spring. And he said… In those days you couldn’t phone underground. The signals wouldn’t go out. So I could only phone once. I got at out at Silver Spring. And so he said, “Yes, I’ve reached home. I’ll come fetch you.”

Shane Hanlon: 26:58 Do you remember where you were on 9/11?

Vicky Thompson: 26:58 I do. I was in college. I was in an early, early morning class. So when I came out of the class, it was like the campus was completely silent, which was very strange. It was like-

Shane Hanlon: 27:13 Did you not know until you came out of class?

Vicky Thompson: 27:13 No, no, no, no.

Shane Hanlon: 27:13 Oh, okay.

Vicky Thompson: 27:18 Yeah, yeah, yeah. And my advisor grabbed me because my mom works in New York City. So my advisor grabbed me, to pull me into his office, to try to get ahold of my mom, which I couldn’t. Everything’s fine, but couldn’t get ahold of her.

27:35 So I went back to my room, and my roommate was sleeping, and there was a post-it note on my desk that said in sleepy penmanship, “Your mom called. She doesn’t know when she’ll get to talk to you, but everything’s fine.”

Shane Hanlon: 27:54 Wow.

Vicky Thompson: 27:55 And my roommate took this message from my frantic mother and then went back to sleep.

Shane Hanlon: 28:00 Went back to sleep.

Vicky Thompson: 28:01 So she was from Syracuse and didn’t have a lot of concept-

Shane Hanlon: 28:01 Okay.

Vicky Thompson: 28:06 … in her sleepy head about what my mother was talking about or what was going on. So she went back to sleep. And then the rest of the day was terrifying.

Shane Hanlon: 28:06 Of course.

Vicky Thompson: 28:06 Obviously, right?

Shane Hanlon: 28:16 Yeah. Yeah.

Vicky Thompson: 28:16 But yeah, that’s where I was.

Shane Hanlon: 28:20 Yeah. I was in ninth grade Spanish class, in my rural Pennsylvania school. When everything started, I remember them, literally, they turned onto TVs. Yeah. That whole rest of the day, I just remember, we went from classroom to classroom, but didn’t do anything. We just watched TV for the rest of the day.

Vicky Thompson: 28:36 Right.

Shane Hanlon: 28:39 I’m, I was going to say, far away from where things happened, and I don’t have a personal relationship to it like you do. But I’m from not very far from Shanksville, where one of the planes went down on the field. That’s about probably less than an hour from where I grew up.

28:56 So while I have this kind of geographic connection to it, I don’t have that personal linkage. I don’t have a parent who was in the city, or even like Hashima, I wasn’t in the DC area at that time. So very happy to hear that things were good for you, Vicky. And things were fine for Hashima as well, even though I’m sure this was a very scary experience, frankly.

29:22 And so she has seen and experienced, frankly, so much over her career. We were really wondering what’s next on the horizon for her.

Hashima Hasan: 29:33 As you may have guessed, my horizon is getting closer and closer to me. It’s not very far in the future. So what time I have left for me, what I would really like to do is, one of these days I should retire. I don’t know, every time I think I’ll do it next year, so maybe.

30:00 But what I would like to do is really take science out to the public. So within the last year, especially after the launch of Hubble, I mean, of JWST, I’ve been getting a lot of requests from schools and other places to give talks on JWST.

30:21 I think that’s something I would like to concentrate on. Taking science to the public. We need to ensure that the misconceptions of science are removed. People should be able to make their own decisions, but they should really value science and look upon it as really an inquiry, inquiry-based activity, and not something which is science fiction. So they have to distinguish between science and science fiction.

30:55 I think educating the public is really the only way. And the earlier you start, the better. As they say, reach for the stars.

Shane Hanlon: 31:21 Hearing these inspiring words from Hashima, I couldn’t help but think back to when we talked about your dreams of becoming a lawyer. And I’m sorry that didn’t happen for you. And I feel personally responsible for guiding you down the path of becoming a podcaster.

Vicky Thompson: 31:44 Yeah. Thanks to you, I’m well on my way to getting podcasting awards.

Shane Hanlon: 31:50 Oh, man.

Vicky Thompson: 31:50 I’m sure they’re going to add a podcast category to the EGOT thing we were talking about.

Shane Hanlon: 31:50 Funny, you laugh.

Vicky Thompson: 31:50 I’ll be there.

Shane Hanlon: 31:56 I wonder if someday there will be an audio something version. I don’t know. Not what we’re doing, obviously, but long form, narrative stuff. You know what I mean?

Vicky Thompson: 32:08 Is there not in Grammy’s or in-

Shane Hanlon: 32:11 So, yes. So right now, it’s under Grammy’s. A lot of-

Vicky Thompson: 32:14 Oh, it is?

Shane Hanlon: 32:15 Many… Yeah. I think, I want to say many, but I know some folks who have gotten EGOTs, which is weirdly becoming also a theme of this podcast. I have no idea how.

32:24 Some of them are for spoken word, whether that’s for narration or for personal story, whatever it is.

Vicky Thompson: 32:29 Okay. Okay.

Shane Hanlon: 32:29 So, it is under Grammy right now.

Vicky Thompson: 32:31 Okay.

Shane Hanlon: 32:31 But maybe they’ll pop it out to make a separate category. What would it be?

Vicky Thompson: 32:31 Yeah.

Shane Hanlon: 32:38 Would it be… It would be the PEGOT. P-E-G-O-T.

Vicky Thompson: 32:44 Oh, it’d be great. It’d be great.

Shane Hanlon: 32:45 I’m sure people would love that.

Vicky Thompson: 32:47 Runaway.

Shane Hanlon: 32:49 Well, I think that’s enough from us, talking about podcasting or otherwise. And I want to thank Hashima for sharing her amazing stories with us. And with that, that’s all from Third Pod From The Sun.

Vicky Thompson: 33:04 Special thanks to Jason Rodriguez for conducting the interview, and to NASA for sponsoring the series.

Shane Hanlon: 33:10 This episode was produced by Zoe Swiss and me, with audio engineering from Collin Warren, and artwork from Karen Romano Young.

Vicky Thompson: 33:18 We’d love to hear your thoughts, so please rate and review us. And you can find new episodes on your favorite podcasting app or at thirdpodfromthesun.com.

Shane Hanlon: 33:26 Thanks, all. And we’ll see you next week.

33:35 Hi, Vicky.

Vicky Thompson: 33:36 Hi, Shane.

Shane Hanlon: 33:37 What’s the coolest thing you’ve ever… You’re getting two today. Does this count?

Vicky Thompson: 33:50 Oh.

Shane Hanlon: 33:50 Does me writing one as O-N-E, instead of W-O-N.

Vicky Thompson: 33:55 I knew what you meant.

Shane Hanlon: 33:57 I love that you were just waiting for it too.

Vicky Thompson: 33:57 I had read the sentence three times to make it work.

Shane Hanlon: 34:01 You’re just like, wait until this idiot gets to this one, and realizes he says, what’s the coolest thing you’ve ever O-N-E?

Vicky Thompson: 34:10 Because first I said… First, I thought you meant owned. My brain was just like, owned.

Shane Hanlon: 34:13 Oh, sure.

Vicky Thompson: 34:13 Like a particular object.

Shane Hanlon: 34:13 Yeah.

Vicky Thompson: 34:14 And then I was like, door prize?

Shane Hanlon: 34:16 Yeah.

Vicky Thompson: 34:16 Anyway. Okay, let’s do it again.

Shane Hanlon: 34:18 Oh my gosh. Doing well. Okay.