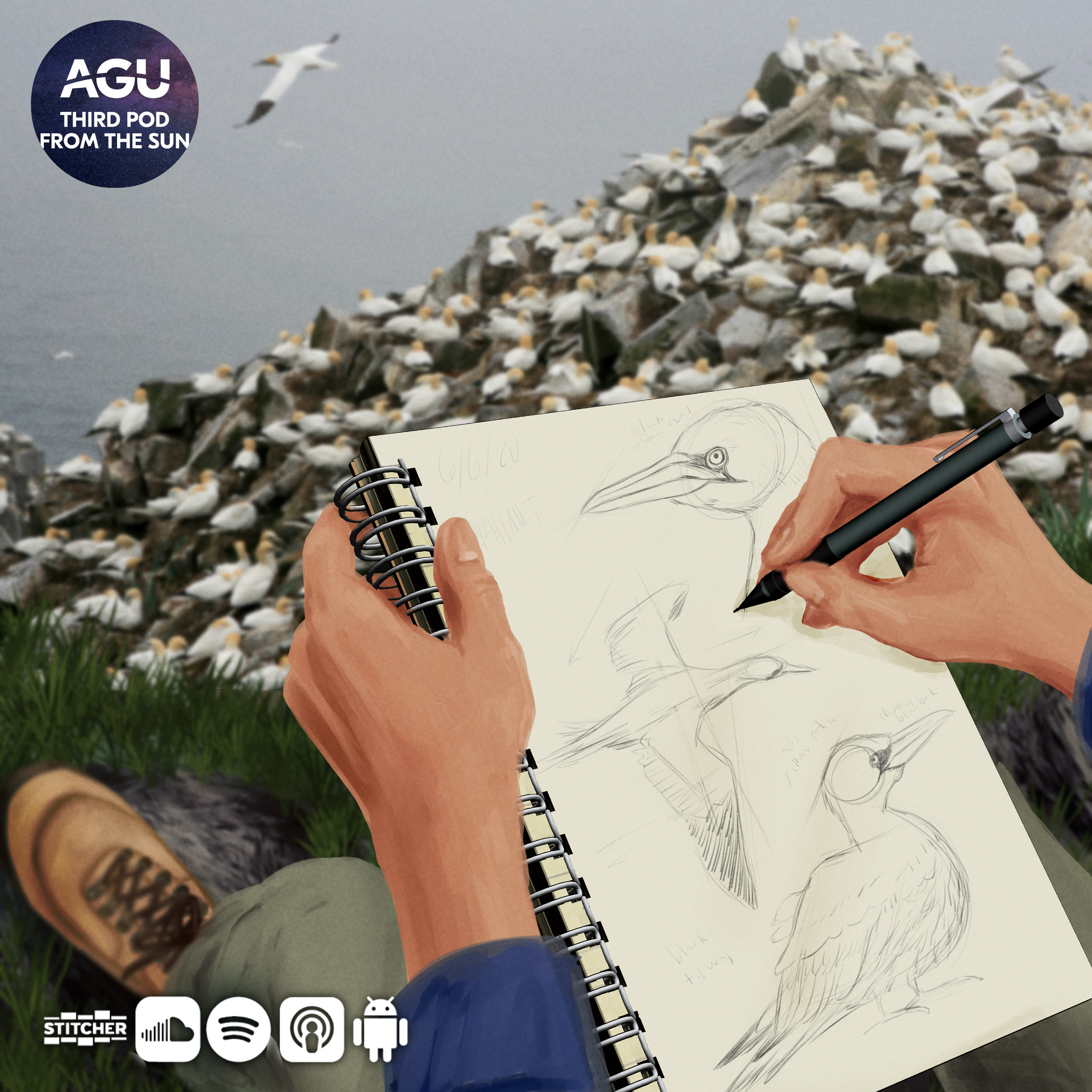

Fieldwork rocks: Picturing science

Joris De Raedt, a passionate scientific illustrator dedicated to capturing the beauty and significance of nature through his art, strives to foster a deep connection between people and the fauna and flora that inhabit our world. Despite utilizing modern tools like a graphic tablet, his illustrations pay homage to a timeless style of documenting the natural world.

Joris De Raedt, a passionate scientific illustrator dedicated to capturing the beauty and significance of nature through his art, strives to foster a deep connection between people and the fauna and flora that inhabit our world. Despite utilizing modern tools like a graphic tablet, his illustrations pay homage to a timeless style of documenting the natural world.

Joris’s field experiences, both alongside his family and within various projects, have enriched his understanding of the intricate relationships within ecosystems. Through his art, he aspires to instill a sense of respect for nature and highlight the immense value of endangered species and ecosystems.

This episode was produced by Anupama Chandrasekaran and mixed by Collin Warren. Artwork by Jace Steiner.

Transcript

Shane Hanlon: 00:00 Hi, Vicky.

Vicky Thompson: 00:01 Hi, Shane.

Shane Hanlon: 00:02 Imagine you are in the field. You’re a scientist out in the field, or not, or just some person out in nature.

Vicky Thompson: 00:10 Just a human.

Shane Hanlon: 00:10 Yeah. And you are interrupted by a cassowary. First off, do you know what a cassowary is?

Vicky Thompson: 00:18 I sort of did. I Googled them to reacquaint myself. Yeah. No, I don’t want to imagine what you’re saying. I don’t want to see one in real life. They’re so scary.

Shane Hanlon: 00:29 They are terrifying raptor birds.

Vicky Thompson: 00:35 Yeah.

Shane Hanlon: 00:36 Weirdly enough, I’m not going to say I have a story about a cassowary, but I used to… And if folks have been listening for quite some time, they might be familiar with this, but I used to work/volunteer part-time at our zoo here in DC. I haven’t been to the zoo in years, but at least at the time, they had a couple of cassowaries, I believe. And something about, I don’t know if this is for all zoos, but for ours, at least, if something really bad happens, that’s actually a Code Green because they don’t want to freak people out if something… You know what I mean? You don’t want to say, “Code red,” right? So everything’s reversed. And I actually don’t think they had a Code Red. I think it was orange, yellow, red or orange, yellow, green, whatever. But a Code Green. And Code Greens, there aren’t many things that can be Code Greens. It’s basically-

Vicky Thompson: 00:36 I don’t know. At the zoo?

Shane Hanlon: 01:35 It’s basically if a really bad animal-

Vicky Thompson: 01:36 Like the highest, the worst, worst, worst.

Shane Hanlon: 01:38 Yeah. Like a really predatory one gets out. And from talking to a lot of keepers and everything, I would always ask them, what’s the animal you would be most afraid of? And to almost a person, it wasn’t the lions or the cheetahs. Cheetahs actually aren’t that bad. Or even some of the wolves, I don’t know, some of the stereotypical things people would think, “Oh, my gosh, you’d be so scared of it.” Cassowaries. They are afraid of the cassowaries because, yeah, they are prehistoric raptor birds.

Vicky Thompson: 02:11 Are they just murderous?

Shane Hanlon: 02:13 Yeah. I don’t want to anthropomorphize my perceptions onto these birds, but just looking at them, I am very impressed and simultaneously quite terrified.

Vicky Thompson: 02:27 Yeah, they’re like space creature birds, as well.

Shane Hanlon: 02:29 Space creature birds.

Vicky Thompson: 02:33 No, really. They’re made-up horror movie birds.

Shane Hanlon: 02:37 They are. They are. Yeah. So I’m happy that I was never in a situation where I came across one.

Vicky Thompson: 02:46 Uh-uh.

Shane Hanlon: 02:52 Science is fascinating, but don’t just take my word for it. Join us as we hear stories from scientists for everyone. I’m Shane Hanlon.

Vicky Thompson: 02:52 And I’m Vicki Thompson.

Shane Hanlon: 03:03 And this is Third Pod from the Sun. So I certainly don’t wish a cassowary upon you, Vicki.

Vicky Thompson: 03:15 Oh, thanks. That’s like the least you can do, caring about not wanting the most dangerous bird ever to hurt me. Thank you.

Shane Hanlon: 03:24 Anytime, Vicky, I’m really here for you. And, yeah, frankly, if one of them did get close to me, I would just run far, far away. And our guest today, a scientific illustrator, experienced this actually for real, out in the field.

Vicky Thompson: 03:40 What?

Shane Hanlon: 03:41 Yeah.

Vicky Thompson: 03:41 They ran into one for real?

Shane Hanlon: 03:45 A cassowary actually just peered over his shoulder as he was just intently sketching some leaf.

Vicky Thompson: 03:52 Oh.

Shane Hanlon: 03:52 Yeah. So I can’t wait to hear more. And so for that, I’m going to bring in producer Anupama Chandrasekaran to tell us more. Hi, Anupama.

Anupama Chandrasekaran: 03:59 Hi, Shane.

Vicky Thompson: 04:00 Anupama, who did you speak to for this episode?

Anupama Chandrasekaran: 04:04 I spoke to Joris De Raedt. He’s a scientific illustrator. I mean, an artist, basically, who’s been drawing flora and fauna as far as he can remember, since he was a kid.

Shane Hanlon: 04:18 I mean, in the day and age now where things like photographs are just so prevalent, can illustrations still be relevant?

Anupama Chandrasekaran: 04:29 I think so because I see photographs all the time, and now it’s just become de rigueur. But when I see an illustration, it actually catches my attention. And it’s also got this old world feel to it, an old world appeal, and it’s got more aesthetics, I think, than a photograph. But what I really found interesting was that, as an illustrator, you think he’d have a desk job, but turns out that field work is really integral to his work.

Vicky Thompson: 05:01 Oh, okay. I’m excited about this one. Let’s hear it.

Joris De Raedt: 05:08 I’m Joris De Raedt. I’m from Belgium. I’m a full-time scientific illustrator. I’ve been at it for the last 10 years. Field work is a very important aspect of my job because I always try to see my subjects in the field, preferably in their natural habitat whenever possible. I get a sense of their character and how they behave, so when I make the eventual illustration, I can really try to put the essence of the animal in there.

Anupama Chandrasekaran: 05:47 Could you tell us a little bit about what inspired you to become a nature illustrator?

Joris De Raedt: 05:53 I’ve been drawing as long as I can remember, really. My interest in the natural world was sparked at a very early age, as well, because my parents were both teachers and we traveled a lot. I remember when I was a kid, I always could sit in front of the car because I was great at spotting things, so I had to sit in front. And at one point I thought I saw some sand walking when we were driving through the Atlas Mountains in Morocco. And it turned out to be my very first chameleon I saw. I was also very inspired by natural history plates and 19th century explorers and the art they made, especially the aesthetic part of the plates, the combination of the illustrations and the typography.

Anupama Chandrasekaran: 06:42 What were some of your first field experiences that made you think that, “Well, this could be it”?

Joris De Raedt: 06:51 I got two, actually, what I can think of. The first one was still when I was very young. We were on this trip in Scandinavia and we had the canoes with us, and at some point we saw a small island offshore, which had a big colony of puffins on there. And my parents decided like, “Oh, wow, we want to see that.” And we took the canoes on the sea, which they aren’t really built for. But anyway, we went and we went very close and they were flying by us and they were so curious. And then it didn’t turn out very good when we returned because the boats flipped in the waves when we went back to shore because they weren’t really built for it.

07:32 But anyway, in the evening I made sketches of these puffins, and that was really one moment during my youth that I was like, “Wow, this is really, really what I love to do.” And then later on when I made the switch from biology to visual arts at uni, I really tried to include nature in my work. And so the summer before my bachelor project, the first project that I could really choose the entire thing, what I would do, we were traveling to Australia, so I had the dream of doing something with bowerbirds. They’re like the artist of the birds. They build these cool structures and decorate it.

Anupama Chandrasekaran: 08:17 They’re stunning, aren’t they?

Joris De Raedt: 08:18 Yeah, they’re just amazing. And then finding the first bower was extremely hard for me. I didn’t know what to look for. I read about them, but we were traveling in a group, as well. It was with my parents, with friends. But then after a while, I really got to learn the birds so good that, even from the car, when I saw a specific bush, I could say there would probably be a bower underneath. And I was right in many of the cases.

08:45 That’s when I really learned the importance of field work. The better your subject, the better your project will be, and you know what you’re talking about. I know there’s the internet today, so you can draw whatever you want. You find references enough. But if you don’t understand the species, I guess, I feel a bit handicapped.

Anupama Chandrasekaran: 09:20 You spoke of how important it is to be in the field. Could you connect that to your whole process of working and explain what it is like to work in the field by giving us some examples and why that is integral to your work?

Joris De Raedt: 09:35 If I worked on my Raptor & Owls book, for example, my parents have a little cottage in the forest in Sweden. So I lived there for two months during winter, which was pretty challenging because every time I needed to go to the supermarket, I had to get this old Land Rover started and get the snow chains on and see that I get off the hill safely. But it was great because it was minus 25 degrees Celsius out there. And I saw about an observation five days in a row of the great gray owl, and I always wanted to see them hunting in the snow.

10:15 So I was invited by these people, and in the morning I got to see these owls hunting. I think you can really study how they move, the tactics they use. Sometimes they sit on this birch before catching the mice. Sometimes they hover above the snow and then drop before getting up with the mice. But it’s these moments that really they inspire me. Not only do they inspire me to start at these illustrations, but also you get familiar with their anatomy and you also get a better sense of how you will visualize the action.

Anupama Chandrasekaran: 10:59 You need to show how cunning they are, right?

Joris De Raedt: 11:00 Yeah, yeah. And these expressions, I feel like the best way to learn their characters is just to see them move and see them do their thing.

Shane Hanlon: 11:16 I did fieldwork, as we’ve talked about before, but I wasn’t an animal behaviorist when I was a researcher. So I wouldn’t have thought observing and studying animal behavior would be so integral to illustrating, I guess.

Vicky Thompson: 11:31 That makes sense because I guess as much as it is about documenting everything correctly, it’s also about capturing the spirit of the thing that you’re drawing, too.

Anupama Chandrasekaran: 11:42 Yeah. I mean, no, I totally agree with you, Vicky. It is about the spirit and to actually show a snapshot of an animal behavior, you really need to observe it on the field, and you have to really imbibe those qualities of that plant or bird or animal or a cat or whatever you see. And well, having said that, his field work, Joris’ field work isn’t necessarily just about being outdoors. It’s also about, say for example, a visit to the museum where he goes behind the scenes and he checks out specimens. That also is part of his field work.

12:26 Can you tell me the different kinds of field work that you do, even going to the museum is field work, for instance, right?

Joris De Raedt: 12:43 Well, the most flexible kind is I travel and I keep a nature journal and everything that I see that it’s special or that catches my eye, I will sketch or I make notes of them. I keep these journals constantly, so I bring them with me. During these travels, it’s often a bit of finding a balance. Will I be sketching them from live the whole day or will I be photographing them, which gives me more time to explore more and see more species? That’s always a hard decision.

13:18 And then there are times that I need to draw species that are very hard to see or find, and then I can visit the archives of a museum. But, although I really love the atmosphere there, it’s not easy because the stuffed birds, they’re the static skins, actually. They’re all lying on their back, so you can’t open the wings or anything. The paws are dried up. They don’t have the proper color anymore. So it’s only good for specific research to go there, but still, it can help sometimes.

Anupama Chandrasekaran: 13:59 Do you have any funny or memorable experiences from field?

Joris De Raedt: 14:05 Yeah, let’s take you back to Australia, because two years ago I was there for a year.

Anupama Chandrasekaran: 14:12 Two years ago? That’s during the pandemic.

Joris De Raedt: 14:15 Yes, I’ve been stuck on Tasmania for seven months. Not stuck. I didn’t mind, though. There were worse places to be stuck. Even when we arrived in 2019, in November, there were huge bush fires so we had to change plans from our tour that we wanted to make from the start. So then we went to Tasmania, and when the pandemic broke out, we were there. Later that year, we made it back to Queensland. And I remember this time that I had a lot of assignments coming in because I work freelance. I don’t always know when a commission will come in.

14:57 And I was working on this campsite with my foldable table underneath a rooftop tent in the shade near a rainforest and I heard something behind me. I was really scared at a point because there was this huge southern cassowary behind me. I’m not sure if you know these birds, but they can be so aggressive. It came toward me and it was looking at my screen because I was drawing a leaf or something. And I really feared for my laptop screen for a second, but luckily it was more interested in the food that was in the trunk, so that was weird. That’s a special moment.

Anupama Chandrasekaran: 15:42 Can you describe some moments where you were really awestruck with the beauty of what you saw, where you just kept your pen down and you just watched without drawing, because that is what this kind of canvas deserved?

Joris De Raedt: 15:57 I actually often have that feeling, but the thing that pops up in mind now is last summer I was in Iceland and we hiked to this cliff where there was a huge colony of gannets just in front of us, not so far off. They’re so massive and so many of them, and we were so close and there was no one else. I wanted to start working at my painting and started sketching, but I just couldn’t. I was just observing them for an hour or so before I took up my pen.

16:36 In Australia, I had the same moment when I was looking at riflebirds. This is a kind of bird of paradise and they’re doing this dance, and I wanted to see that for such a long time. So when I was there, it took me a long time before I saw them doing the dance, though. But even when I saw the birds for the first time, it just blew my mind, observing them, seeing all these beautiful details, the way they were moving. I couldn’t believe that I was there. I felt like in a BBC documentary or something.

Shane Hanlon: 17:16 That’s wild. I’ve had some compelling memories in the field, but nothing compares to this. I knew some folks who studied scrub jays. These are really smart birds in central Florida who have wild and, frankly, scary memories, but they’re honestly not really much to look at.

Vicky Thompson: 17:34 Oh, I only have scary memories of raccoons and rats in the city. I feel like that’s all I have.

Shane Hanlon: 17:43 What’s funny is I didn’t really grow up with rats, being out in the country, but we definitely had a lot of raccoons.

Vicky Thompson: 17:48 Raccoons?

Shane Hanlon: 17:50 But I feel like we’re getting off-topic. I’ll swing things back to Anupama.

Anupama Chandrasekaran: 17:56 No, no. I mean, rats really, I can totally recollect an episode where we were in the Andaman Islands and we lost our oil bottles, and it was because of a huge rat, which we never really thought it was a rat. We just thought somebody among the staff stole it. But coming back to Joris, another thing that really struck me about him and about the way he works is what he is doing to actually be authentic to his work. And what he told me was that he no longer just jets in and out of places to do his field trip, but he actually spends a lot of time.

18:32 When I spoke to him, he was actually in this long hiatus in Greece where he was studying and drawing things. I mean, he is really taking time to do things a little slowly, and I think that really makes his field work quite serious. And it’s really about spending many months in some places, sometimes even as long as a year in the field.

18:54 Could you list your wishlist or your bucket list of places and field-work sites that you would like to go to actually do drawings of specific creatures that you have been very intrigued by?

Joris De Raedt: 19:18 Yeah. Well, I think on the top of the list, it’s top one New Guinea to see the birds-of-paradise and bowerbirds. This group of birds have always fascinated me so much. They’re just like the top of the mountain when it comes to evolution. I’ve been in Australia and actually one of my biggest idols, William T. Cooper, he’s an Australian artist who painted all the birds-of-paradise and bowerbirds. He made amazing, amazing books about them. I actually visited his studio two years ago, which was very cool, and I will go back there later this year.

19:56 But what I loved for the last few years, I’ve been able to stay for a longer time in a certain place, and that’s really my dream for the future. I don’t want to visit a country for two weeks and go back home, so I’ve got the stress of wanting to see all of these species in a small time. I can work from wherever in the world, so why not work from there for a while? Like I’m in Greece now for a few months. It’s just great exploring new terrain, finding new species, and getting connected with the people and seeing how nature still or doesn’t live in their culture.

Anupama Chandrasekaran: 20:39 Yeah. No, that makes sense. That makes sense. Give me a sense of how you have incorporated technology or digital tools in your work.

Joris De Raedt: 20:54 Well, when I grew up, I went to art school in the weekends, one day a week, and that was all traditional, of course. But then the summer when I decided to start my master’s in graphic design, I had a holiday job in the Breeding Center for Endangered Arabian Wildlife in the UAE. I spent two weeks in the birth department and two weeks in the reptile department and the head of reptiles, he was working on a field guide at the time of the snakes of the UAE, and he was a digital artist, so I could see his work. He was working on this with this Wacom tablet. I never saw that, this big tablet.

21:32 So I decided to put all my earnings that I made that month in my first Wacom tablet. In the field, I’ve tried to work on an iPad, for example, but it just didn’t work for me. I still love these traditional techniques, feeling the paper underneath my hand and trying to control the watercolor. I just miss that in my digital work often.

Anupama Chandrasekaran: 21:57 Yeah, yeah. And I mean, for me, the big lesson has also been how being on the field, because one would think, being an illustrator, being at your desk and drawing, is all. Because one of the points you mentioned, actually, if you want to address that bit, why does it require so much of homework, so much of field work to make a meaningful single drawing?

Joris De Raedt: 22:24 Yeah. Well, I look at a lot of work of other artists, and I can almost immediately tell when a painting is made from photos and they don’t have seen their actual animal. Not always, but often I can see it, just because the posture is not very typical for that species or there’s something wrong with how it’s visualized with the background. I don’t know. It’s both a thing of importance for my work, I guess, as it is just highly motivating to be out in the field and inspirational to start at your work. Most of my inspiration of drawings that I’m doing for myself or even for clients, like behavioral things, they just come up in the field without me knowing it before I started, before I went there.

Vicky Thompson: 23:41 Shane, did you ever draw anything that you studied?

Shane Hanlon: 23:43 Oh, no, absolutely not. That is not a skill that I possess, and I recognize that you don’t have to be “good” at drawing, but frankly, it just wasn’t for me. Though our colleague, Olivia, who has drawn some stuff for the podcast, she’s a great example of someone who is good at drawing and can actually draw what she studied in the field. Anupama, do you draw? Is this a thing that you possess?

Anupama Chandrasekaran: 24:13 I do, and I actually find it a way of just mulling over the subject that I’m working on. For instance, when I did a podcast on fossils, I used to actually draw some of these fossils, and then as you draw, you just get ideas and you understand it a little better or questions crop up. So, again, I’m not a great artist, but it actually helps me kind of digest that subject a little bit more when I draw.

Shane Hanlon: 24:41 And, Vicky, you’re a visual artist.

Vicky Thompson: 24:43 Yeah, I really like that. I was actually painting some shells earlier in the week, and I feel like I never… Sometimes you’re around something so much and you don’t really look at it, and when you draw it, you realize, “Oh, I’ve looked at this, but I’ve never really looked at it,” until you start drawing it, so I like that.

Shane Hanlon: 25:02 Maybe this explains part of why I am the way I am, and I just don’t appreciate the visual beauty around me. That’s why I do audio, so I don’t have to actually look at things.

Anupama Chandrasekaran: 25:12 Wow. I’m sure there’s more to that.

Shane Hanlon: 25:15 I’m sure, yeah. Well, with that, that is all from Third Pod from the Sun.

Vicky Thompson: 25:21 Thanks so much to Anupama for bringing us the story, and to Joris for sharing his work with us.

Shane Hanlon: 25:25 This episode was produced by Anupama with audio engineering from Colin Warren and artwork by Jay Steiner.

Vicky Thompson: 25:31 We’d love to hear your thoughts on the podcast, so please rate and review us, and you can find new episodes on your favorite podcasting app or at thirdpodfromthesun.com.

Shane Hanlon: 25:39 Thanks all, and we’ll see you next week.

Vicky Thompson: 25:48 How tall are they? Are they like-

Shane Hanlon: 25:51 They’re actually not super big. They’re smaller. They’re emu-sized, I believe.

Vicky Thompson: 25:55 That’s pretty big. My eye just fell on dwarf cassowary.

Shane Hanlon: 26:01 Are they cuter? Are they like-

Vicky Thompson: 26:03 Oh, it’s just the word. I don’t know. Oh, wait. No. Oh, no. That is possibly worse. It’s got like a bulbus-

Shane Hanlon: 26:12 Oh, my gosh. Now I need-

Vicky Thompson: 26:15 It looks like its whole head is beak. I imagine it might not be hard, but it looks like perhaps its whole head is hard.

Shane Hanlon: 26:24 Oh, yeah.

Vicky Thompson: 26:24 They’ve got a big-

Shane Hanlon: 26:26 They’re prehistoric.

Vicky Thompson: 26:27 No, that’s true. Oh, my God. I just keep saying, “Oh, my God.”

Shane Hanlon: 26:35 “Cassowaries are 3.2 to 4.4 feet tall.”

Vicky Thompson: 26:40 They’ve got spike heads, spine heads.

Shane Hanlon: 26:48 This is one of the few times where I wish we were primarily a video medium, because just watching you click through things and your face. It’s just like the horror.

Vicky Thompson: 26:58 It’s like they really are prehistoric. They have dinosaur bits on top of their heads.

Shane Hanlon: 27:05 Yeah. Yep.