Invisible forces: Sharpening our cosmic vision

When you look up into the night sky, what do you see? Is it a clear picture? Do you see anything at all? What if we could enhance our view of the cosmos and develop technology that promises to clear away cosmic blur?

When you look up into the night sky, what do you see? Is it a clear picture? Do you see anything at all? What if we could enhance our view of the cosmos and develop technology that promises to clear away cosmic blur?

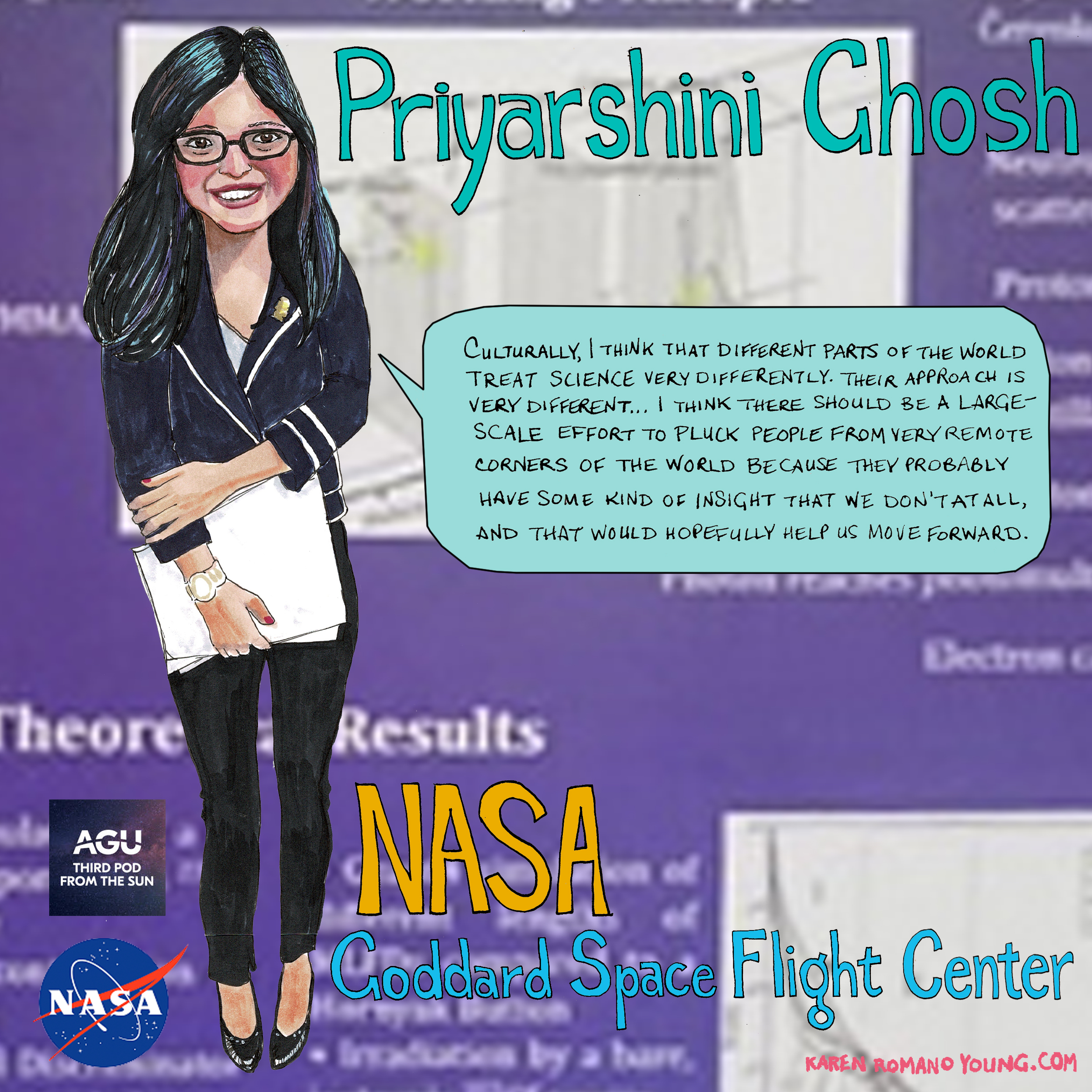

We talked with astrophysicist and nuclear engineer Priya Ghosh, a postdoctoral researcher at NASA Goddard Space Flight Center, who builds and develops radiation detectors to detect neutrons and gamma rays, and also studies and analyzes cosmic ray data to understand better the chemical composition of the galaxy. We chatted with her about changing the narrative on nuclear energy, writing magical realism fiction, and trying to build a good pair of eyeglasses so the galaxy becomes less blurry.

This episode was produced by Shane M Hanlon, and mixed by Collin Warren. Artwork by Karen Romano Young. Interviews conducted by Jason Rodriguez.

Transcript

Shane Hanlon: 00:00 Hi, Vicky.

Vicky Thompson: 00:01 Hi, Shane.

Shane Hanlon: 00:02 When you think of radiation, as much as one does in their everyday lives, what comes to mind?

Vicky Thompson: 00:10 Is radon the same as radiation?

Shane Hanlon: 00:13 Vicki, don’t. Stop. No, the answer is no. I was going to say, don’t ask me questions I don’t know the answer to. The answer is-

Vicky Thompson: 00:20 It’s not.

Shane Hanlon: 00:20 It’s not the same thing. See, this is the thing.

Vicky Thompson: 00:24 See, now we don’t know.

Shane Hanlon: 00:25 I know.

Vicky Thompson: 00:25 Because that’s what came to mind.

Shane Hanlon: 00:27 No. But what I know, I mean, people get radon and stuff in their basements and that’s bad, but it’s not radiation bad.

Vicky Thompson: 00:31 It’s not radiation bad.

Shane Hanlon: 00:35 We’ll do some digging and come back to this.

Vicky Thompson: 00:37 Okay. Yeah, we’ll figure it out.

Shane Hanlon: 00:38 Okay. So you think of something that may or may not have anything to do with radiation. For me, I think of The Incredible Hulk. Have you ever read comics or watched the shows or any of the movies? Any of the Marvel stuff?

Vicky Thompson: 00:51 Yes. I know The Incredible Hulk.

Shane Hanlon: 00:53 Okay.

Vicky Thompson: 00:53 Not watched the comics, but have you seen the She-Hulk ones?

Shane Hanlon: 00:57 Watched the comics?

Vicky Thompson: 00:57 Oh, watched the comics. Read the comics.

Shane Hanlon: 00:59 You’ve watched the comics. Have I seen-

Vicky Thompson: 01:00 Have you-

Shane Hanlon: 01:01 … the show?

Vicky Thompson: 01:01 She-Hulk, yeah.

Shane Hanlon: 01:02 Oh my gosh, I love the show. Did you see the show?

Vicky Thompson: 01:05 Oh, do you? Just the coming attractions. It makes me giggle.

Shane Hanlon: 01:11 So you brought it up to make a point, and then you didn’t even end up watching the show.

Vicky Thompson: 01:15 Oh, I didn’t bring it up to make any kind of point. I almost never bring things up to make points.

Shane Hanlon: 01:19 You were just curious.

Vicky Thompson: 01:21 It just came into my head, so it came out of my mouth.

Shane Hanlon: 01:24 I have to say, I like Marvel stuff. I watch the movies and the shows and all of that, and I have thoughts on Hulk, whatever. But She-Hulk, I actually really liked She-Hulk. Well, here’s the thing. I like good entertainment. Or I like entertainment, good or otherwise. I wasn’t really a comics person. I think the gender politics in the comics weren’t great, honestly.

Vicky Thompson: 01:49 Sure. Right.

Shane Hanlon: 01:49 A lot of things in the comics weren’t great, frankly. But the show, say what you will about it, it did a really good job at addressing some of those historic issues in a really poignant, but yet, I think, fun and entertaining way.

Vicky Thompson: 02:05 Okay. Well, I’m glad we had this opportunity to talk about She-Hulk.

Shane Hanlon: 02:10 Yeah, I am excited you actually brought it up. I was going to bring it up first. So look at us. We’re on the same wavelength today.

02:21 Science is fascinating, but don’t just take my word for it. Join us as we hear stories from scientists, for everyone. I’m Shane Hanlon.

Vicky Thompson: 02:30 And I’m Vicky Thompson.

Shane Hanlon: 02:32 And this is Third Pod from the Sun.

02:38 I really love the idea of the fact that in the prompt, I had actually written down that I wanted to talk about She-Hulk. And Vicki, you just brought it up unprompted.

Vicky Thompson: 02:49 Just out with it.

Shane Hanlon: 02:50 Oh my gosh.

Vicky Thompson: 02:51 Just out with it.

Shane Hanlon: 02:51 Look at us. But we should move from my nerdy nerd fandom corner, and we’ll get back to science corner for this episode.

Vicky Thompson: 03:02 We’re not going to go rogue and just do nerdy nerd, Marvel nerd.

Shane Hanlon: 03:06 No, no. There’s enough of those kind of Phantom podcasts out there.

Vicky Thompson: 03:11 Sure.

Shane Hanlon: 03:11 And I listen to many of them. And honestly, I don’t think AGU would be too happy about me just turning this into a Marvel podcast.

Vicky Thompson: 03:19 Sure.

Shane Hanlon: 03:20 We don’t need that. But we are here today to talk about radiation. That’s where we started. So there is a tie-in here.

Vicky Thompson: 03:29 And I know how happy it makes you to connect seemingly unconnected topics.

Shane Hanlon: 03:34 Oh, I love a segue. It brings me so much joy. So with that, let’s get into it. Our interviewer was Jason Rodriguez.

Priya Ghosh: 03:44 My name is Priya. I am a postdoctoral researcher at NASA Goddard Space Flight Center, and my position is a astrophysicist and a nuclear engineer. I build and develop radiation detectors to detect neutrons and gamma rays, and also I study and analyze cosmic ray data to understand better the chemical composition of the galaxy.

Jason Rodriguez: 04:14 That’s great. And within all that, if you could sum it down, what exactly do you do in all of that?

Priya Ghosh: 04:23 I actually do two separate things. One part is the engineer part, where I am building radiation detectors, and these are mostly employed, for example, I’ll give you an example. So we all know about lightning and stuff, or we think we know, but recently, we found out that lightnings also emit gamma radiation, but we don’t know anything about it. So one of the things we’re doing right now is we’re building a detector, and we’re flying it on an airplane above the Caribbean, where we know there will be lightning strikes. And so we want to study the gamma radiation coming from lightning, and also to understand what exactly is happening within lightning, which a lot of it we actually do not know. So my job would be to build those gamma radiation detector and put it on board the plane and make sure it works.

Jason Rodriguez: 05:16 I was reading something that you said, I have a quote here. You say, “I’m trying to build a good pair of eyeglasses so the galaxy becomes less blurry.” So what’s so important about understanding these cosmic rays and what you’re studying?

Priya Ghosh: 05:29 So if we look at, say, 1930s, when the golden age of physics was happening, there were a lot of new discoveries, like new particles, new laws. I mean, Einstein’s greatest laws and stuff. And those are the biggest discoveries that gave us a picture of what could be out there, but we still didn’t know. Suppose people predicted there could be things like a black hole and all. But now, so cosmic rays, these are just charged particles. So you have the periodic table, all the elements on the periodic table. So they’re strewn all over the galaxy.

06:07 And so an event happens like, say, a supernova, death of a star. They emit these highly charged particles from all over the periodic table. And so we collect these data. Some of them we collect on Earth, some of them we collect from the ISS. And so these detectors collect this cosmic radiation. And so when we study how much of a certain element is there, like suppose Iron-56, we try to see how much of iron there is, how much of, say, zinc there is. And that can give us an idea of how these elements are distributed across the galaxy. And then we can tell, okay, “So this much of iron exists” or “This much of zinc exists.”

Shane Hanlon: 06:56 Vicky, how much iron do you think exists in our galaxy?

Vicky Thompson: 07:01 What a wild question to ask somebody.

Shane Hanlon: 07:06 Your face.

Vicky Thompson: 07:07 I just got whiplash.

Shane Hanlon: 07:10 “What?”

Vicky Thompson: 07:13 What? How dare you ask me that.

Shane Hanlon: 07:14 No, seriously, how much? What are we talking about here? What even units of measurement are you going to give me for this?

Vicky Thompson: 07:20 No, I don’t know.

Shane Hanlon: 07:20 Are we talking about cubic feet of iron?

Vicky Thompson: 07:23 In the galaxy.

Shane Hanlon: 07:24 In the galaxy.

Vicky Thompson: 07:25 So I feel like four Earths’ worth.

Shane Hanlon: 07:27 Whoa. That’s-

Vicky Thompson: 07:29 I don’t know.

Shane Hanlon: 07:30 I have no idea, either, but that’s really good social math. That’s a unit of measurement that, yeah, that’s good communication right there.

Vicky Thompson: 07:37 Thanks.

Shane Hanlon: 07:38 Yeah. In all fairness, I don’t even know how much iron exists inside of me, so I’ll just leave those bigger questions to Priya. But we were wondering how, or frankly, why did she even get into asking those big questions?

Jason Rodriguez: 07:54 And so how did that land you at NASA?

Priya Ghosh: 07:57 Actually, it’s funny, because I was not going to come to NASA. I got a job at Berkeley Lab, where I really did want to go, because I had a set project there, and I knew the people there. But my advisor did not wish for me to take that job. And so I had to actually look for something else. But luckily, I found NASA, and it was the perfect project for me, because it was an amalgamation of all the skills that I had learned up till then. And I could also fulfill my dream of being, well, not a space scientist, but working in astrophysics in some manner. So that’s how I ended up at NASA.

08:39 Actually, my mom helped me get the job, because I told her that I was very interested in doing something in astrophysics, finally. And so my parents are both very supportive. So my mom, she keeps searching the internet and she’s like, “Hey, would you be interested in this?” And then I emailed the person who was on that job list, the scientist, and she’s my boss now.

Jason Rodriguez: 09:03 Wow. Thanks, Mom. So you just sent a cold email and then here you are?

Priya Ghosh: 09:07 I mean, yes. She interviewed me and everything, but yes.

Shane Hanlon: 09:15 Have you ever had a parent help you out with job, getting a job? In a job?

Vicky Thompson: 09:21 Yeah, actually my mom, I would say, got me my first office internship-

Shane Hanlon: 09:30 Oh.

Vicky Thompson: 09:30 … when I was in college at a book publisher.

Shane Hanlon: 09:33 Oh, that’s cool.

Vicky Thompson: 09:33 Yeah.

Shane Hanlon: 09:34 Do you like it?

Vicky Thompson: 09:35 Yeah, I loved it.

Shane Hanlon: 09:36 Oh.

Vicky Thompson: 09:36 I really did. Yeah, it was fun.

Shane Hanlon: 09:38 Well, that’s nice.

Vicky Thompson: 09:40 Yeah.

Shane Hanlon: 09:40 Growing up, I definitely had an assist. I worked on a neighbor’s ranch. I probably talked about this before, but basically, I was a legacy employee. I am four of four in my family.

Vicky Thompson: 09:53 Right.

Shane Hanlon: 09:53 I have three brothers, and so I was the fourth one to work on this ranch.

Vicky Thompson: 09:58 Yeah. So you had to? Or they had to let you?

Shane Hanlon: 10:03 Oh, interesting. No, I basically think I had to. Some of my brothers worked longer there than others, but it was just assumed that you were going to go work at the ranch. Yeah.

Vicky Thompson: 10:13 Yeah. So did you do anything on the ranch that you’re super-proud of?

Shane Hanlon: 10:23 I mowed. I was really great at mowing and weed-eating. I was fantastic at it.

Vicky Thompson: 10:30 Weed eating.

Shane Hanlon: 10:30 Weed eating, weed whacking, I don’t know what people call it these days, but I never did anything that quite stacks up to some of the stuff that Priya has done.

Priya Ghosh: 10:39 So I was on an internship at Idaho National Lab, and me and my boss, we invented a very novel, first-of-its-kind quantum dot neutron detector. It’s the first neutron detector which employs quantum dots, which is a very new frontier in technology. Quantum dots are on TV. It makes your TV screens brighter, but we’re using it as a neutron detector, and we’re using it for security purposes, to detect materials like bombs and stuff. But this could be of far more efficient detectors than the type of materials we use right now. And so we just patented it two months ago.

Jason Rodriguez: 11:20 Wow.

Priya Ghosh: 11:20 So that is a very big professional achievement for me.

Jason Rodriguez: 11:25 Congratulations.

Priya Ghosh: 11:27 Thank you. Thank you so much. I would be happy to tell you more about it if anyone’s ever interested in it. But personally, I think, there’s-

Jason Rodriguez: 11:35 Oh, and what was it called?

Priya Ghosh: 11:37 It’s called SHINE. It’s actually gel detector. So it can be made into any shape and size that the application requires, which is also a first. And it has quantum dots, which are so small, they’re on nanoscale level. They’re so small, their properties are actually size-dependent. So depending on the nanoparticle size, you can change their properties and color properties, the colors they emit. And so the radiation, basically, the neutrons or gamma radiation basically is turned into light.

Jason Rodriguez: 12:16 Wow.

Priya Ghosh: 12:16 And so I think it will be a very big new technology, given that it’s far more efficient than regular scintillator detectors, which is a very common gamma radiation detector, a neutron detector as well. But also the fact that it is like a shapeshifter. It can change shapes.

Jason Rodriguez: 12:35 Oh, wow.

Priya Ghosh: 12:35 So based on whatever application you want. So I think that’s going to be a huge new technology. And even though I don’t work on it anymore, I no longer work there, I still talk about it to people and give talks about it. When I first moved to the US to do nuclear engineering, I think my friends and family were a little concerned that I would be around radiation all the time, and so was I, because going to be around gamma ray sources and neutron sources all the time.

13:06 So I think they were a little concerned, but as I kept studying the field, and I also did a lot of advocacy for nuclear energy. So slowly over time, I think my friends and family, they not only know that I’m not in any danger, they fully understand the benefits of nuclear energy, and I think they have gone around telling their friends and family about nuclear energy, about its benefits. About how it’s not as scary as a comic book would portray it.

Jason Rodriguez: 13:40 So what makes this important to you, this change in narrative on nuclear energy?

Priya Ghosh: 13:55 So when I first started out in 2015, a lot of nuclear power plants, especially in the US, were actually being shut down. Some of the reasons are obviously economic, and building a nuclear power plant is actually very expensive. Starting it and building it, the infrastructure cost. But the energy itself is actually very cheap once it’s built, and it’s also very, very safe. But accidents like the Three Mile Island, Chernobyl, Nobel, Fukushima, they have had a negative impact on how public view nuclear energy. And a lot of people have been a little wary of it, wary of having their energy supplied from nuclear energy, or having nuclear power plants in their country. But it really isn’t as dangerous as has been portrayed or has been communicated. And so I think it is very important that we do significantly have more nuclear power plants, because solar and all the renewables, they’re not very reliable.

15:03 What if you have a cloudy day? Or what if you don’t have wind or areas that don’t have wind? Obviously, coal and everything, they are non-renewable, but nuclear energy is actually very, very clean. It’s actually cleaner than even renewables, like solar and wind. And so I think it is important that people learn to trust the science of nuclear energy without having to understand the little details about atomic physics. But people need to trust it, which at this point, a lot of people don’t. So I think it would be great for people to be more trustful. So anything anyone can do, advocacy would be great. So I think, yeah, that’s why I did some advocacy for it.

Vicky Thompson: 16:03 I feel like nuclear isn’t talked about in the same way like solar or wind.

Shane Hanlon: 16:08 Right. And like Priya mentioned, it’s probably because the stigma associated with the handful of really well-known disasters. I mean, Three Mile Island in Pennsylvania happened only a couple of hours from where we are right now. But it’s not going away. And it’s a good reminder, it’s good to have folks like Priya to communicate the facts, rather than people like us talking about, I don’t know, Hulk or Godzilla or something like that.

Vicky Thompson: 16:37 You use “us” pretty liberally there. I think I don’t want to be included in the us.

Shane Hanlon: 16:42 Okay. Fair. Just me. People like me using things like Hulk and Godzilla. I guess I just really like a good story. And as it turns out, so does Priya.

Priya Ghosh: 16:53 I’m also a fiction writer. I used to write for a newspaper, nonfiction when I was back in India. I used to write for a paper. But after I moved here, I’ve been a little preoccupied with my PhD. But now that I have a job, I’m getting back into it, and I’ve gotten back to writing fiction and waiting to publish.

Shane Hanlon: 17:14 Nice. What kind of fiction, can I ask?

Priya Ghosh: 17:16 Yeah, I write on the magic realism genre.

Shane Hanlon: 17:20 Yes.

Priya Ghosh: 17:20 And I like to write about the human mind and how we work, how we react to certain situations, why we react to certain situations. Just about the human mind, and how interesting and non-interesting people operate. I even know somebody who came from fashion designing into science, because that person worked on a lot of fabrics, different kinds of fabrics in his fashion designing time. And then when he moved to science, he was working with a particular type of fabric that could help generate energy. I’m not sure exactly how, but such a transition is even more extreme. But it’s fascinating, because why would you want to always think, “Oh, physics, I should be in physics,” or this or so interchanging fields. I find that very fascinating.

Shane Hanlon: 18:21 I feel like I’m the opposite of the person that Priya was talking about that she knows. I transitioned from science into podcasting, or I guess at least partially.

Vicky Thompson: 18:31 Right. But there’s room for both things, like both sides of your brain.

Shane Hanlon: 18:34 Yeah. No, I mean, I hope so at least. And I still love science. I get to learn about things every day. And honestly, I sat in, I was in the background for this interview. I was running the tech while Jason and Priya were talking, and it was super-interesting. I was especially learning a bunch of things when I was listening to interviews for folks as interesting as Priya.

Priya Ghosh: 18:56 So most of our galaxy, more than 80% is made of hydrogen, and then there’s a bit of helium. So if you look at the periodic table, there’s hydrogen, helium, and then all sorts of other elements in ascending order of weight. So we know hydrogen, we know helium, we know boron, carbon, but we know lesser of what’s going on with these elements which are higher weight. And once we get to know what amount of these higher elements are, we will get to know, for example, iron. If we do find a good percentage of iron, which is also quite heavyweight, we will be able to uncover further the mechanisms of, say, a supernova. So we know a lot about it, but there’s a lot we don’t know.

19:55 So there was a scientist, I forgot who it was, who said that all the discoveries in science has already been made. What we need now is more precise data. Because again, we do have a picture. It’s a very blurry picture. And so we’re trying to get more accurate data of these higher elements so that we can get a much more cleaner picture. Actually, right now, I don’t know if you have the same issue with my video, but I think my internet’s bad, and I see a very blurry image of you. And that’s what we see right now of the galaxy. We have a very blurry vision, but if the internet works, I will see you clearly again. And that’s what our detector right now that’s going to go up to ISS is going to try to do. It’s going to try to make it less blurry.

Jason Rodriguez: 20:44 That’s lovely. And what’s the hope of getting this more crisp picture out of it, out of the universe?

Priya Ghosh: 20:59 What do you mean? What’s the hope?

Jason Rodriguez: 20:59 Why is it so important to see it in such a broad spectrum and not so blurry? What are we hoping to truly understand, or what is the project trying to find, I suppose?

Priya Ghosh: 21:10 Again, a greater understanding, because we have a limited understanding of what’s there in the galaxy. We don’t know a lot of processes. And not only do we not know what processes there are, the cosmic rays coming from wherever their origin is, like, say, the supernova in coming to between there and being detected at our detector on Earth or on orbit, there’s a lot of things happening in the middle to those cosmic radiation, whatever it goes through. And we do not know a lot of those mechanisms. Is it accelerating? Is it getting deflected somewhere else? Is it diffusing? We have very less idea. And so this will give us an idea of a little clearer image of what might be happening.

Vicky Thompson: 22:01 Okay. So Shane, as a self-proclaimed lover of science knowledge, would you like to expand on the work that Priya’s doing?

Shane Hanlon: 22:09 Like to? Yeah. Able to? Absolutely not.

Vicky Thompson: 22:14 That’s probably for the best. So I imagine that Priya had some advice on how best to work together to keep doing some really great science.

Priya Ghosh: 22:23 Culturally, I think that even different parts of the world treat science very differently. Their approach is very different. And I mean, not like it doesn’t happen right now, but I think it would be even better if this was a more common thing to do, but to hire people from places or from experiences where we generally would not pick someone from. For example, somebody, say, who’s not had much education in science or does not even have the means to have education in science, but is very intelligent in day-to-day matters, or is good with people problems. I think there should be a large-scale effort to pluck people from very remote corners of the world, because they probably have some kind of insight that we don’t at all, and that would hopefully help us move forward.

Shane Hanlon: 23:34 I love this idea of looking outside our circles to find the best folks at the job. I mean, it sounds intuitive as the words leave my mouth, but honestly, I don’t know how often this happens.

Vicky Thompson: 23:48 Yeah, I mean, on a much smaller scale, and maybe less important scale, I guess. I don’t know. You asked me to be your co-host, and I’m not a science communicator.

Shane Hanlon: 23:57 Oh, not on a smaller scale. It means so much to me, Vicky.

Vicky Thompson: 24:00 Aww.

Shane Hanlon: 24:01 True. Yeah, sure. That’s true from a, I guess, profession level. But you’re especially great at calling me on my BS, and that’s probably a more necessary skill to have, frankly.

Vicky Thompson: 24:13 It’s half my job.

Shane Hanlon: 24:17 Oh, you say that with such relish.

Vicky Thompson: 24:20 Yeah.

Shane Hanlon: 24:20 Oh, well, before we bring you too much glee, let’s wrap it up. So with that, that’s all from Third Pod from the Sun.

Vicky Thompson: 24:29 Special thanks to Jason Rodriguez for conducting the interview and to NASA for sponsoring the series.

Shane Hanlon: 24:34 This episode was produced by me, with audio engineering from Colin Warren and artwork by Karen Romano Young.

Vicky Thompson: 24:41 We’d love to hear your thoughts. So please rate and review us, and you can find new episodes on your favorite podcasting app or at ThirdPodfromtheSun.com.

Shane Hanlon: 24:49 Thanks, all, and we’ll see you next week.

Vicky Thompson: 24:57 About radon.

Shane Hanlon: 24:59 About radon, because we were going to come back to it and we never came back to it.

Vicky Thompson: 25:02 Oh, okay. Okay. Did you go back to it? Did you look it up?

Shane Hanlon: 25:10 Yeah. So I did some Googling. And from the CDC, radon is an odorless, invisible, radioactive gas, naturally released from rocks, soil, and water. Radon can get into homes and buildings through small cracks or holes and build up in the air. Over time, breathing in high levels of radon can can cause lung cancer. So you’re right.

Vicky Thompson: 25:40 Sorry, I didn’t know what to say at the end.

Shane Hanlon: 25:44 I’m so cheery about this-

Vicky Thompson: 25:46 Lung cancer.

Shane Hanlon: 25:46 … really terrible thing. Well, so I’m in my basement, my studio is in my basement and our-

Vicky Thompson: 25:54 Do you have a mitigation system?

Shane Hanlon: 25:56 No, but the smoke detector we have down here is also a radon detector and other things. And I guess our whole house should be like this. I don’t know. When we moved in, it was like this, but it’s the only one that it has more than a battery. It’s actually looped into our power system, because fires are bad, obviously. But for detecting gas and radon and things like that is especially bad, if you’re breathing in and over time. So not a mitigation system. And growing up, I know we had a little bit of an issue with radon. We had to do something, but I think underground basements, they’re just supposed to have detectors for it.

Vicky Thompson: 26:43 Yeah, really, I mean, I live in Maryland, and I know it’s super-common in Maryland. So our house has a mitigation system, and actually, something’s wrong with our gauge right now. So that’s pretty cool.

Shane Hanlon: 27:00 What is the mitigation?

Vicky Thompson: 27:05 I wonder if I’m calling it the wrong thing, now that you asked me that.

Shane Hanlon: 27:08 We’ll just add it to another episode. We’ll just keep, radon will be-

Vicky Thompson: 27:11 It’s a thing that goes on the ground, and then it goes out of the house.

Shane Hanlon: 27:17 Oh, it might be a pump of some sort or something like that?

Vicky Thompson: 27:19 Yeah. Maybe it just lets it out. Because it-

Shane Hanlon: 27:22 It vents it?

Vicky Thompson: 27:23 Yeah.

Shane Hanlon: 27:25 Look how much we’re learning.

Vicky Thompson: 27:27 Yeah. I still don’t feel like I know, but-

Shane Hanlon: 27:33 We’re done learning for today.

Vicky Thompson: 27:35 Okay.

Shane Hanlon: 27:35 All right.

Vicky Thompson: 27:36 No more of that.