Invisible forces: Fielding Earth’s magnetic mysteries

What was the first big project you worked on at your job? An important report? An interesting experiment?

What was the first big project you worked on at your job? An important report? An interesting experiment?

How about helping to build a satellite?

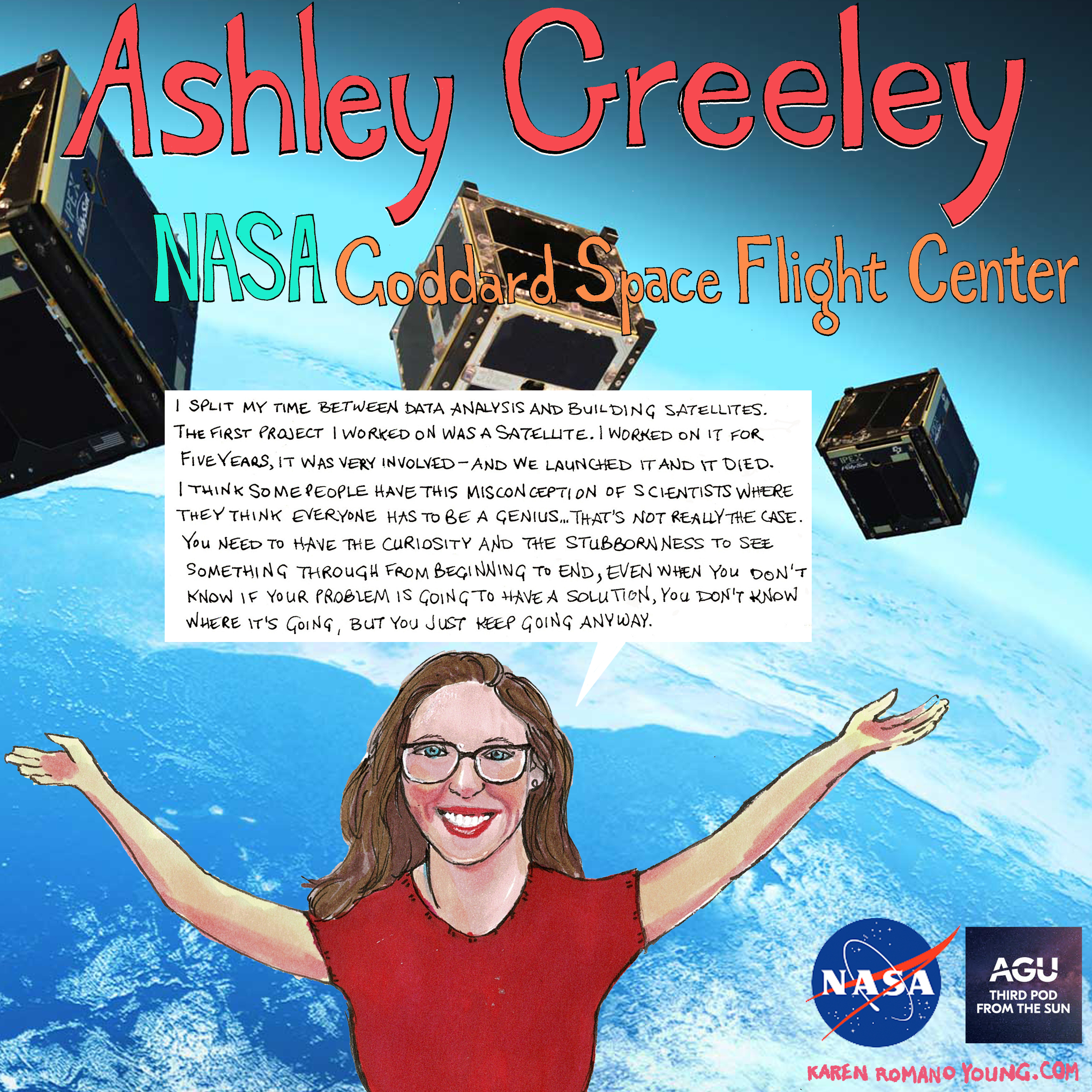

Ashley Greeley, research scientist in the Heliophysics Division at NASA Goddard Space Flight Center, joined us to talk about becoming an expect in talking about imposter syndrome, building innovative devices that measure radiation from space weather, and how stubbornness can be an asset for a budding scientist.

This episode was produced by Shane M Hanlon, and mixed by Collin Warren. Artwork by Karen Romano Young. Interviews conducted by Jason Rodriguez.

Transcript

Shane Hanlon: 00:00 Hi, Vicky.

Vicky Thompson: 00:00 Hi, Shane.

Shane Hanlon: 00:02 Today we’re talking about branches of physics.

Vicky Thompson: 00:06 Oh.

Shane Hanlon: 00:07 Yeah, I know. And I have a quiz for you.

Vicky Thompson: 00:13 No.

Shane Hanlon: 00:14 That was so much better than I could have imagined. So I’m just going to ignore your protestations and I’ve given you a word bank ahead of time with a handful of different branches of physics. And I mean asterisk on branches of physics. I don’t want anyone adding me, but things that are associated with physics.

Vicky Thompson: 00:33 So technical branches?

Shane Hanlon: 00:36 I’m not going to get into it. Do you want to read them out for the listeners?

Vicky Thompson: 00:40 Yes. Heliophysics, optical physics, astrophysics, geophysics.

Shane Hanlon: 00:49 Okay. To start, what is the study of matter-matter and light-matter interactions?

Vicky Thompson: 00:56 I just want you to say matter again.

Shane Hanlon: 00:58 Matter-matter.

Vicky Thompson: 00:59 Matter-matter? Optical physics.

Shane Hanlon: 01:01 Roger roger. Yes. Good job, Vicky. Okay, so the next one.

Vicky Thompson: 01:07 Okay.

Shane Hanlon: 01:08 Physics in the universe, including the properties and interactions of celestial bodies.

Vicky Thompson: 01:14 Astrophysics.

Shane Hanlon: 01:16 I wish people could see how proud of yourself you are right now.

Vicky Thompson: 01:20 So weirdly last week my sister gave me a big foam finger and I wish that it was closer to me right now. Okay.

Shane Hanlon: 01:31 Next, the sciences of physical relations on our planet.

Vicky Thompson: 01:39 See, you said that in a tricky way. Our planet, geophysics.

Shane Hanlon: 01:43 Yes.

Vicky Thompson: 01:43 Okay.

Shane Hanlon: 01:45 And finally, I guess by process of elimination, the science of understanding the sun and its interactions with earth and the solar system, including space weather.

Vicky Thompson: 01:55 Heliophysics.

Shane Hanlon: 01:55 Good job, Vicky.

Vicky Thompson: 01:56 Thank you.

Shane Hanlon: 01:56 I’m so proud of you.

Vicky Thompson: 01:58 I’ve worked at AGU for 12 years.

Shane Hanlon: 02:00 You’re number one in my book.

Vicky Thompson: 02:01 That’s literally the only reason I know. Thank you. I don’t even need my foam finger.

Shane Hanlon: 02:10 Science is fascinating, but don’t just take my word for it. Join us as we hear stories from scientists or everyone. I’m Shane Hanlon.

Vicky Thompson: 02:20 And I’m Vicky Thompson.

Shane Hanlon: 02:21 And this is Third Pod from the Sun. Okay, so before I made this caveat up top, but before anyone can comment that some of these aren’t perfect comparisons and arguably not physics, I know. Just I know.

Vicky Thompson: 02:40 I think that I was going to say we should be really accurate because we’re communicating science. We’re a science communication podcast, but I feel like actually where you and I are not consistently accurate, so I think it’s okay.

Shane Hanlon: 02:56 Well, we’re not trying to spread falsehoods or anything by any means. It’s a game. I like to have fun sometimes at your or, frankly, sometimes at my expense. So here we are, but there was a purpose to all of this. So of these words I gave you in this word bank, we’re talking today with someone who studies heliophysics. So she works with Vicky.

Vicky Thompson: 03:21 Wait, I have to scroll back up. Physics in the universe, including the properties and interactions of celestial bodies.

Shane Hanlon: 03:30 No, that’s not the right one.

Vicky Thompson: 03:32 I scrolled up too far.

Shane Hanlon: 03:34 This is so much better.

Vicky Thompson: 03:38 No.

Shane Hanlon: 03:38 Yeah. No, that’s astrophysics.

Vicky Thompson: 03:43 Okay. Okay. Okay. The science of understanding the sun and its interactions, including space weather and blah, blah, blah. The earth and the solar system.

Shane Hanlon: 03:50 Very good, Vicky.

Vicky Thompson: 03:51 Thank you.

Shane Hanlon: 03:52 All right, so before we dig ourselves into a deeper hole, we’ll just get into it. Our interviewer was Jason Rodriguez.

Ashley Greeley: 04:07 My name is Ashley Greeley. I work for Goddard Space Flight Center with NASA and I’m a research scientist. So I’m in the heliophysics division and that spans a whole range of topics all the way from the sun to the earth because the sun does interact with our earth, its magnetic fields, its atmosphere. So what I study in particular tends towards the magnetic fields surrounding the earth called the radiation belts. I study particles, what they do, how they change, how those populations can affect us. And on a practical matter, I sort of split my time between data analysis and building satellites. So it’s kind of fun to get the hardware and the data analysis in there.

Shane Hanlon: 05:04 Vicky, what amazing thing do you split your time with? So there’s talking to me and then what else?

Vicky Thompson: 05:13 Wait, okay. So in this comparison, are you the satellite or are you the busy work?

Shane Hanlon: 05:19 Goodness, that’s a great question. I’ll be the more mundane stuff.

Vicky Thompson: 05:24 Okay.

Shane Hanlon: 05:25 I’ll own that.

Vicky Thompson: 05:26 Yeah, so in AGU land I work to help members connect with the programs that AGU puts together that they really want to support. I think that that’s like a satellite. That’s like building a satellite.

Shane Hanlon: 05:41 That’s a really great answer, Vicky. What happens when all the great work you’re doing doesn’t quite yield the desired results?

Ashley Greeley: 05:51 The first project I worked on was a satellite that I worked on for five years was very involved and we launched it and it died. So that was called CERES. It was a CubeSat that my then advisor had proposed right as I was arriving at NASA. We got a quick signal from it and then lost communications and never heard from it again. And that was really disappointing and we did a lot of rethinking over was there things we could have done differently. Did this need to go the way it did? And ultimately, it’s hard to say because we don’t really know what happened, but that’s just the way it goes sometimes. So it was a really cool experience because when I say CubeSat, I’m talking literally the size of a shoebox. It was small. And because it was so small, I was able to get in the ground floor of a project very early on in my career, see it from start to finish.

06:50 It was intending to look at electrons and protons in earth’s radiation belt. I started in doing simulations to we have these computer packages so that we can sort of figure out in advance how the particles are going to interact with matter, do some calibrations of the detectors, put the whole thing together. It was really cool to touch an instrument that was going to go into space as a grad student. That was just so crazy. I did just get some funding. It’s my first proposal, actually, which was really exciting.

Jason Rodriguez: 07:23 Wow. Congratulations.

Ashley Greeley: 07:24 Thank you. It was an internal funding to develop a space weather instrument. So my CoI and I will be, that’s coinvestigator, will be looking into finding the optimal design for a new space weather particle instrument where electronics and computers have improved so much in the past decades that we’re able to do some really cool, interesting science in some really compact packages and really small instruments. So we’re seeing how high of an energy we can get to basically while still keeping the instrument fairly small so that it costs us money. There’s a little less development into it. We could hopefully get it off the ground figuratively and literally quicker.

Jason Rodriguez: 08:09 No, that’s amazing. If you can share with us, what is the mission or the goal of this project, of this proposal?

Ashley Greeley: 08:18 Yeah. This is a little farther out in space than my usual instruments, which are in the radiation belts. So we’ll go out into space. It is still looking at solar, wind products. We’re hoping to solar energetic particles, SCPs and GCR is galactic cosmic rays. Some of those have pretty high energies, much higher than I’m used to dealing with. And so we want to be able to measure the spectra, the higher range of ions and protons because there’s a couple of missions that are reaching their end of life. And so we’re going to have sort of a gap there in the future where we’re not taking those measurements. And that’s really important to do. Not just to have the observational capabilities to do that for pure science research, but one of NASA’s goals is to study space hazards and radiation in the lunar region for the future Artemis missions. So we really need to fully understand those higher energy ions and how they’re acting so that we can protect our astronauts and our instruments that are going to be out near the moon.

Vicky Thompson: 09:42 Would you ever want to go into space?

Shane Hanlon: 09:44 I feel like we’ve talked about this before, but hard no. Absolutely not. There are too many things to worry about. I mean, beyond the whole vacuum of space thing, which is terrifying, I didn’t even think about high energy ions. I can’t imagine those being good for us.

Vicky Thompson: 10:03 No, probably not. But as Ashley is thinking about these big important concepts, does doubt ever settle in that maybe she can’t do it?

Shane Hanlon: 10:12 Yeah. Yeah, definitely. And she talked about that she’s experienced some pretty major imposter syndrome, but has also had some really great opportunities to be part of the conversation around it.

Ashley Greeley: 10:23 I think one of my favorite moments I guess as far as making progress in people’s understanding of imposter syndrome was at a conference. We had some round tables with students and later career people and I asked the senior scientists if they had ever experienced imposter syndrome. They were all immediately uncomfortable, but they also all said that, yes, they had. And just the look on the student’s face, you could tell it was really important for them to hear that. So I mean, I’m still working on it myself as well.

Jason Rodriguez: 11:00 Me, too.

Ashley Greeley: 11:01 You, too. Yeah. It’s a shame, really, because we’re doing really cool stuff where I love the research I’m doing, but there’s just something that’s still it’s me holding me back and it’s really hard to get rid of.

Shane Hanlon: 11:24 Do you have a favorite in-person, in public personal achievement, like a moment when you were in front of a crowd or a group and did or said something that you were especially proud of?

Vicky Thompson: 11:35 No, I don’t think I have any of those. I actually have to, probably not as much as you, but I have to talk in front of crowds of people quite a bit, especially at AGU meetings and things. And I’m just excited when I get off the stage without any major problems.

Shane Hanlon: 11:54 I mean, that’s an achievement. The stakes can be whatever you make them. If it’s important to you, it’s important to everyone else, right?

Vicky Thompson: 12:01 Sure.

Shane Hanlon: 12:02 Yeah. And I mean, for Ashley, that moment talking about imposter syndrome was a really big deal, but I mean, she’s also had some incredible moments when it comes to research.

Ashley Greeley: 12:14 Personal achievements. I hate to kind of tie it back into the science, but really getting my PhD was huge. I didn’t come from a family that had a lot of higher education. My mom is an extremely talented artist, but she didn’t go to college. And my dad got his associates when I was a young child, so that was something that my parents were always just really supportive and really proud. But I kind of bumbled my way through it, maybe a little more than someone whose parents both went to school. I didn’t really know what I was doing with student loans, for example. That was fun. And so just experiencing that with my family was really important to me. I think my dad might’ve even been prouder than I was when I got my degree and that was just really special. It was a little disappointing.

13:15 Both my parents were at my thesis defense, which was at the end of 2019, but then I was supposed to have my graduation ceremony May 2020. So I didn’t walk, which for some people wasn’t important, but for me it was something that I just wanted to experience with my family. I had already bought the hood and the gown and everything, the silly hat. So I brought them down over Christmas, took some pictures of the family and just to recreate that a little bit because it was something that was really important for me to share with them. So I guess I see it through the eyes of my family and so that’s why I’m so proud of that.

Vicky Thompson: 14:00 Shane, did you walk for your graduation?

Shane Hanlon: 14:03 Well, for a PhD, no. I didn’t go to my ceremony because I graduated midyear and I would’ve had to come back. I graduated early, which like ha-ha. Anyways, but for undergrad, my class, I went to a big public university and my class was so big that no one walked. Literally just all of the biology majors stood up and then people clapped and then we all sat down. Yeah.

Vicky Thompson: 14:31 Bummer.

Shane Hanlon: 14:32 Yeah.

Vicky Thompson: 14:33 But did you do well in college? Would you have gotten acclimates on stage?

Shane Hanlon: 14:38 Well enough, let’s say. I mean, I ended up getting a PhD, so I guess I did okay. Right?

Vicky Thompson: 14:44 Good enough.

Shane Hanlon: 14:45 Yeah. I mean, honestly, though, I think a lot more went into my success beyond just getting good grades.

Ashley Greeley: 14:53 Yeah. Actually, I think that sort of the quality that can make for a good research scientist is being stubborn, getting your teeth into a problem and then not being willing to let it go until you figure it out. I always find it interesting. I think some people have this misconception of scientists, where they think that everyone has to be a genius, got A pluses all through school or something like that and that’s not really the case. They have the curiosity and they have the stubbornness to see something through from beginning to end, even when you don’t know if your problem’s going to have a solution, you don’t really know where it’s going to go, but just to keep going anyway.

Shane Hanlon: 15:41 Are you a stubborn person? Would you consider yourself a stubborn person?

Vicky Thompson: 15:45 Oh, my God, you know the answer to that. I’m so stubborn. I’m like to spite myself stubborn person. Yeah.

Shane Hanlon: 15:55 That’s interesting.

Vicky Thompson: 15:55 Yeah. Are you stubborn?

Shane Hanlon: 15:58 Yeah, I am. I’d like to think that I’ve gotten better, that I pick my battles these days. I think I care about less or fewer small things, which is probably a good thing.

Vicky Thompson: 16:09 That’s really good.

Shane Hanlon: 16:09 But it does creep in once in a while. I mean, there was just even recently, I was messing around with a door that goes into our back. We have a screened in porch and it’s just off. And I finally realized that the door itself, it’s skewed a little bit. It’s warped a little bit and so nothing I could do could make it square, but I was so obsessed with it that I ended up missing lunch with a friend. And literally she texted me, she’s like, “Hey, I’m here.” I said, “No.” I said, “Here’s the deal.” And I told her what happened. She said, “Yeah, you’re awful, but I also understand that. So we’ll just reschedule.” So yeah, sometimes to my own detriment, but hopefully not as much as it used to be.

Vicky Thompson: 16:54 See, but the door won.

Shane Hanlon: 16:57 The door did win. But now honestly, the door is still kind of messed up and I could just get a new one. But also, we might be doing some stuff to the porch. It doesn’t matter. So literally it’s turning into a … It’s doing this. What is that, a parallelogram? It’s turning into a parallelogram almost, where it used to be a rectangle and now one side’s shifting up and one side shifting down. And so I keep sawing off the bottom so it doesn’t drag. So now I’m just correcting it. I’m not even obsessing with it anymore.

Vicky Thompson: 17:29 Well, we can discuss further solutions later, but it’s laughing at you.

Shane Hanlon: 17:34 And with that, that is all from Third Pod from the Sun.

Vicky Thompson: 17:40 Special thanks to Jason Rodriguez for conducting the interview and to NASA for sponsoring the series.

Shane Hanlon: 17:45 This episode was produced by me with audio engineering from Colin Warren and artwork by Karen Romano Young.

Vicky Thompson: 17:53 We’d love to hear your thoughts, so please rate and review us. And you can find new episodes on your favorite podcasting app or at thirdpodfromthesun.com.

Shane Hanlon: 18:01 Thanks all and we’ll see you next week. What happens when all of the great work you’re doing doesn’t quite yield the desired results? Okay, you’re not supposed to answer that.

Vicky Thompson: 18:17 I know.

Shane Hanlon: 18:17 Okay.

Vicky Thompson: 18:19 I knew because there was no space and because you put your hand up so aggressively.

Shane Hanlon: 18:24 Well, I mean, sometimes you don’t read ahead and sometimes you do inappropriately, so I never know with you. You’re kind of a wild card when it comes to script reading.