Invisible forces: Gravity of the (Venus) situation

What goes up must come down, right? Well, what if things go up and come down slightly slower than you might expect? Are there balloons attached? Filled with helium?

What goes up must come down, right? Well, what if things go up and come down slightly slower than you might expect? Are there balloons attached? Filled with helium?

Are you on Venus?

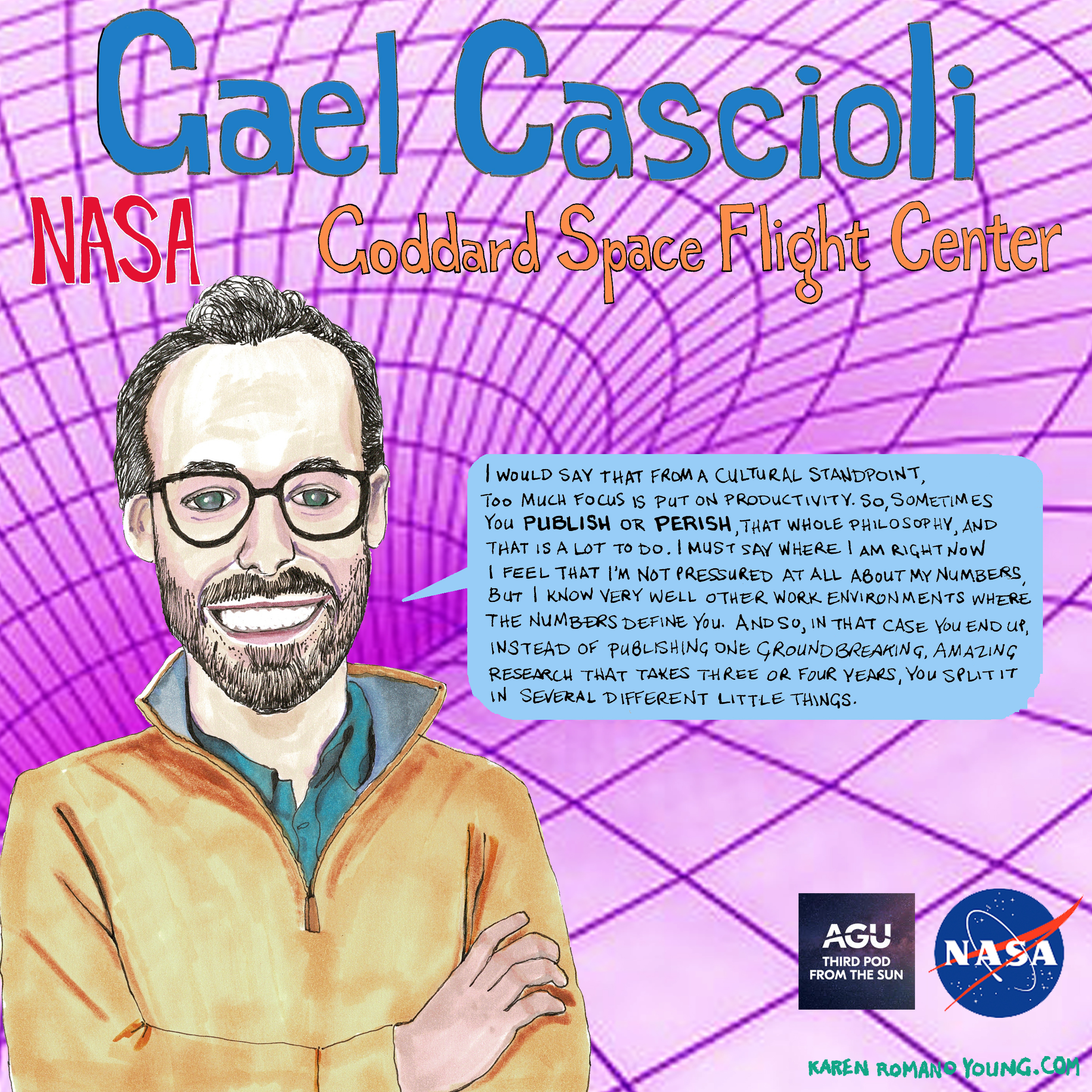

Probably not, but the planet does have a similar gravity to Earth and its planetary scientist Gael Cascioli’s job to learn about gravity on Venus and beyond. We talked with Gael about an upcoming mission to Venus, the importance of diverse collaborations, and why we shouldn’t put some much emphasis on the “publish or perish” model.

This episode was produced by Shane M Hanlon, and mixed by Collin Warren. Artwork by Karen Romano Young. Interviews conducted by Jason Rodriguez.

Transcript

Shane Hanlon: 00:00 Hi, Vicky.

Vicky Thompson: 00:01 Hi, Shane.

Shane Hanlon: 00:02 What’s your favorite planet? I don’t know how we haven’t talked about this before, considering what we do.

Vicky Thompson: 00:07 Yeah, that seems like a real natural question.

Shane Hanlon: 00:09 Do you have a favorite planet that’s not Earth? It can’t be Earth. Besides Earth. We live here.

Vicky Thompson: 00:15 Besides Earth.

Shane Hanlon: 00:16 Right.

Vicky Thompson: 00:16 So I have a favorite, yes. Pluto.

Shane Hanlon: 00:19 Oh.

Vicky Thompson: 00:19 It has always been my favorite planet. Don’t try to ask me things about Pluto because I know nothing about Pluto. But I think I always related to it being the furthest away and also the smallest, like far away and small, and now nobody likes it. And it’s not a planet anymore, right? So.

Shane Hanlon: 00:38 You just went full circle on that whole thing. I was going to say you don’t know much about it, considering that it’s actually not considered a planet anymore.

Vicky Thompson: 00:46 No, but it’ll always be a planet to me.

Shane Hanlon: 00:49 Yeah. So that’s funny. I think Pluto is up there for me. Again, even though it’s considered by most not technically a planet. I don’t traditionally think a ton about space. Jupiter’s neat, but that’s mostly because a lot of realistic science fiction, that’s not quite the word for it, but takes place around Jupiter because of all the moons. It’s this idea, “Oh, if there’s life, it might be on some of Jupiter’s moons,” or things like that. So I think that’s interesting. And then there’s from the time of me being, I don’t know, 10 to maybe now, a special place in my heart for Uranus.

Vicky Thompson: 01:31 Uranus.

Shane Hanlon: 01:32 I can’t tell you why. There’s just something about it.

Vicky Thompson: 01:34 Uranus.

Shane Hanlon: 01:34 Maybe that’s it.

Vicky Thompson: 01:39 Uranus? I’ve never heard someone say it that way.

Shane Hanlon: 01:44 Okay, we’re going to figure this out, the actual… Because that’s the thing. People laugh about the pronunciation of it, but I always thought we just pronounced it wrong, and that’s why people would laugh. It’s like, “Oh, this isn’t actually how you pronounce it. You pronounce it this other way.”

Vicky Thompson: 02:02 Oh.

Shane Hanlon: 02:03 Maybe I’m wrong there, but we’ll do some digging and we’ll get some facts on this podcast.

Vicky Thompson: 02:07 Okay. A little offline googling.

Shane Hanlon: 02:08 Right. Science is fascinating, but don’t just take my word for it. Join us as we hear stories from scientists for everyone. I’m Shane Hanlon.

Vicky Thompson: 02:23 And I’m Vicky Thompson.

Shane Hanlon: 02:24 And this is Third Pod from the Sun. All right, Vicky. So I did some very important research, and turns out there is still disagreement on it. What I could find, and-

Vicky Thompson: 02:39 We can’t agree on anything.

Shane Hanlon: 02:41 Well, so what I could find is that it should be, and traditionally and historically was, Uranus.

Vicky Thompson: 02:47 Right.

Shane Hanlon: 02:48 But because there were some really well-known media events, like there were missions to Uranus, and basically folks got tired of people like me giggling about it.

Vicky Thompson: 03:02 Sure.

Shane Hanlon: 03:03 And so there was this shift to Uranus to prevent literally me from being me in my adolescence. And so I believe… And please don’t at us. I’m probably wrong. You’re probably right, but that’s the confusion, or confusion on my part. I will own all of this. If I am the one who’s in the wrong, I apologize to the space community. But here we are.

Vicky Thompson: 03:33 Just say it’s your Pennsylvania accent.

Shane Hanlon: 03:35 Oh, we could do that. All right, let’s go with that. It’s my Yinzer-not-quite-Yinzer accent.

03:41 But beyond loving the opportunity to be an adolescent boy, we are talking about planets for a reason, but not any of the ones we’ve mentioned. We’re talking about Venus. What do you think about Venus?

Vicky Thompson: 03:53 Ooh. I’ve always liked Venus. Is Venus cloudy?

Shane Hanlon: 03:58 Venus is cloudy, yes.

Vicky Thompson: 04:00 Okay. Well, I’ve always liked Venus because it starts with a V.

Shane Hanlon: 04:04 Oh.

Vicky Thompson: 04:05 And Vicky starts with a V.

Shane Hanlon: 04:06 That makes sense.

Vicky Thompson: 04:06 Yeah.

Shane Hanlon: 04:07 I don’t know a ton about Venus, but our guest today does, among numerous other things. So let’s just get into it. Our interviewer was Jason Rodriguez.

Gael Cascioli: 04:21 So I’m Gael Cascioli. I work for University of Maryland, Baltimore County and NASA Goddard Space Flight Center. I’m a planetary scientist. Actually, I’m a aerospace engineer by training. We can talk about it later. But right now, I’m a planetary scientist. In particular, I focus on planetary geodesy. That is the task of measuring the gravity field and the shape of a planet.

04:48 Well, I’m just back from a two weeks field campaign in Iceland with the JPL-led mission, VERITAS, that is set up to fly to Venus in the next years. And we were there to characterize lava flows and to calibrate our synthetic aperture radar that we will fly. It is, let’s say, a mock-up or a very similar device with respect to the one that we will fly on Venus. So we were there flying the airplane with the radar on it, and we were on the ground trying to get the ground truth for these radar measurements in order to calibrate the instrument. And that was really exciting because it’s getting a little outside of the usual routine of waking up, going to the office, turning on the computer. In that case, we were in the middle of nowhere in the middle of Iceland. And it was really exciting, I must say.

05:35 And it’s a JPL-led mission with collaboration from the Italian Space Agency, the German Space Agency, and the French Space Agency, which is set up to launch in the next years. We don’t have a launch date yet, but it will be around the 2030s. And we are going to orbit Venus. For the first time, a NASA mission will orbit Venus after Magellan. That was in 1994, 1998, more or less. And we are really excited because this will be an amazing mission that will gather foundational data to really understand better the Earth’s twin planet.

06:10 So the basic idea of VERITAS is to provide the most updated and most detailed mapping of the surface of Venus that we have until now and also to understand what are the physical processes on the planet itself. Because one thing that is not clear until now, one of the many things, there are many questions, I can speak for hours about this, but one of the things that we don’t understand is that the surface of Venus is relatively young. But until now, no tectonic processes have been observed. So the question is, how does this work? We don’t know. How is it possible that this surface is so young without active tectonic processes? So this is one of the things that we want to observe.

06:50 And indeed, the radar will do the so-called repeat pass interferometry. So it will pass exactly over the same patch of ground few times, and so we can compare the radar images one with the other and observe change detection to a fairly high level of accuracy. So that will give us the idea of, is there something moving? Is there some tectonic process going on?

07:25 And also, other questions that we want to answer. For example, regarding the rotational motion of Venus, because Venus is, I mean, a very curious object because it’s very similar to the Earth in terms of dimension, surface gravity, the distance from the sun. Of course it’s different, but it’s not that different because the Earth is at one astronomical unit. Venus is, what, is at 0.7. So it’s not that much of a different to justify the fact that Venus is rotating in the opposite sense. And so the sun, instead of rising east, rises west. And so this is something interesting. We don’t know why that happens.

08:02 And also, there is another thing that is happening that all the planetary bodies eventually end up in the so-called tidally lock state. So every planet is not completely symmetric. They’re all, I’ll show it this way, a little bit squished, let’s say. They have a bulge. This bulge eventually, over million, millions and billions of years, tends to align with the central body. So in this case, the sun.

08:28 For the case of Venus, if you do the full computation, you would see that its period of rotation if in a resonance state, that is the one that I just described with the sun and the earth, should be a number. Now that we have precise measurements of its rotational state, we see that it’s slightly off that, but constantly slightly off that. And we don’t have a clear explanation yet about why that’s happening. There are several theories, and we want to test them.

08:52 One of these is that Venus has a very thick atmosphere, very dense atmosphere, and this has strong winds. It is rotating with respect to the planet. And this is due among other effects to the fact that Venus is a slow rotator. So the face that is sunlit and the face that is not sunlit, that is in shade, at very different temperatures. So you have different densities of the atmosphere, and so you have a rearranging of the atmospheric mass. This creates a torque that is in the opposite direction of the torque that would like to stabilize the rotation of Venus. So the idea is that this is the effect that actually keeps Venus in a non-resonant state, but we actually think it could be that. We don’t have a conclusive argument for that.

09:37 And so this is one of the things that we will measure, and I’m really excited to measure [inaudible 00:09:42] in the short-term future. And of course there are many, many, many other questions that we want to answer, but I don’t want to [inaudible 00:09:49].

Jason Rodriguez: 09:48 Thanks for that.

Vicky Thompson: 09:56 So here’s my question. Why should we care about Venus?

Shane Hanlon: 10:01 Well, I mean, Venus is a very important planet that most certainly can show us insights into things like-

Vicky Thompson: 10:08 Okay, stop. You have no idea what you’re talking about.

Shane Hanlon: 10:11 I have no idea, but I know someone who does.

Gael Cascioli: 10:16 So in the wider field, Venus is a key piece in the jigsaw of understanding rocky planets. Because in our solar system, we have Mercury, Venus, Earth, and Mars as rocky planets, and that’s all. And so we need to gather as much information as possible on rocky planets, for example, to understand also what is happening outside our solar system. Indeed, Venus is defined often as the exoplanet in our backyard because it is indeed, in terms of dimensions and shape and temperature, it’s very similar to many exoplanets that we are observing right now. And we have it in our backyard.

10:56 I mean, it’s here. It’s very fast going there. It takes just six months that in space travel, is like nothing. So we can go there almost whenever we want.

11:05 And we want to understand it way better because it has the same shape as the earth, but it’s extremely different. So this is why we want to study it very well, to characterize and try to understand where does this diversity come from and possibly apply this understanding also to exoplanets, of which we just know very few information. In general, temperature, atmospheric composition, dimension, and distance from the star. And if you were to look only at those parameters, many of these would match for the Earth and Venus. Not, of course, the temperature and the composition, but many of those would match. So we want to understand what is it that gives you this broad spectrum within the same dimension, shape, and more or less the same distance from the central star.

Shane Hanlon: 11:59 Does that answer your question?

Vicky Thompson: 12:02 Yeah, I think it does. But I don’t know that I knew Venus was a rocky planet.

Shane Hanlon: 12:07 Honestly, same. I know that it’s not a gas giant. Duh. But for some reason-

Vicky Thompson: 12:13 Duh.

Shane Hanlon: 12:16 We talked about it cloudy. In my mind, for some reason, I had in mind that they were similar somehow.

Vicky Thompson: 12:23 Wow. Yeah, I guess look at us always learning something new.

Shane Hanlon: 12:29 Yeah, yeah. We really appreciate that. Thanks, Gael. But even as skilled and knowledgeable as he is, even he messes up sometimes, right?

Gael Cascioli: 12:40 Well, I mean, many times because you always find a bug in your code. It always happens, right? And sometimes you catch it early, sometimes you catch it a little bit too late.

12:51 And once in particular, I caught one of my bugs a little bit too late. But luckily, I mean, with pulling a few all-nighters, everything was all right, but it required a lot of effort. We were working for VERITAS and we were finalizing the last step of NASA’s decision process to select and then launch the mission where at the end, we had to file the final report, and I had to compute some numbers from simulations. And while they were just finalizing the report, I was going through my code again just to check it, and I found a pretty significant bug, meaning that all the results that I had at that point were not correct. Luckily, I spent many hours without sleeping, but I fixed it and just it works.

Vicky Thompson: 13:45 So Shane, have you ever coded?

Shane Hanlon: 13:48 I would certainly not call myself a coder, no. The closest I ever got was with stats programs when I was a researcher. And I can certainly sympathize from painful personal experience of messing up a small part of the code and it just ruining everything else.

Vicky Thompson: 14:09 Yeah, I remember talking about R, I think. We were talking about R, right?

Shane Hanlon: 14:13 Yes. Yeah.

Vicky Thompson: 14:14 Yes.

Shane Hanlon: 14:15 R was the bane… I liked it when it worked, but was the bane of my existence when it didn’t.

Vicky Thompson: 14:21 Yeah, so you probably weren’t really proud of yourself when you messed everything up, huh?

Shane Hanlon: 14:27 No, no, no. I was not.

Vicky Thompson: 14:31 No. But I bet Gael’s proud of some things that he worked on.

Gael Cascioli: 14:36 And, I mean, in general, also, things that I’m proud of is having set up collaborations with people coming from so many different fields and also personal relationships. That’s what I like, because you can have a very satisfactory professional collaboration without interpersonal, let’s say, closeness.

Jason Rodriguez: 14:57 sure.

Gael Cascioli: 14:58 But you can also have the opposite. And sometimes, the best collaborations that I had were with people that I really care about in general as friends or scientific friends. Let’s call them that way. And that’s something that I really appreciate about this field, this line of work. You get to know a lot of people from all different walks of lives and you also get to know very different cultures. And as I told you at the beginning, first thing I said, I’m a curious person. So that’s perfect for me.

Shane Hanlon: 15:33 Teamwork makes the dream work, Vicky. Your silence is just deafening.

Vicky Thompson: 15:39 Well, it just made me think. I’ve said that before out loud in a real situation and was faced with-

Shane Hanlon: 15:43 Earnestly?

Vicky Thompson: 15:44 Yeah, and was faced with blinking silence. So anyway. So.

Shane Hanlon: 15:53 Oh my gosh.

Vicky Thompson: 15:55 So I just fell completely flat on that. But anyway, back to business.

Shane Hanlon: 15:59 Back to business.

Vicky Thompson: 16:00 Back to business. I was wondering what some of these collaborations and professional relationships really look like.

Gael Cascioli: 16:07 I was at one of my first conferences. I was presenting a poster. And so this guy comes to me with and he had his name tag covered, so I couldn’t read the name. And I was like, “Oh, I like your poster, blah, blah, blah. Let’s talk about something else. If you were to… had the ability of deciding the next mission, where would you send it?” I was like, “Oh, I think that Triton, the moon of Neptune, is very interesting because, I don’t know if you know, it could host a subsurface ocean.” And so he stops and he looks at me and he’s like, “Do you know [inaudible 00:16:40]?” Like, “Oh no.” And he was actually Christian Curana, which was one of the folks involved in discovering the subsurface ocean on the Galilean moon. So I was like, “Okay. Yeah, sorry. I should have seen that coming, but I didn’t know that.” So that was interesting because he was, of course, totally fine-

Jason Rodriguez: 17:00 Yeah, yeah, yeah.

Gael Cascioli: 17:02 He was joking about it. But at the moment, I was like, “Oh no, I can’t.”

Vicky Thompson: 17:10 So has that ever happened to you at a conference?

Shane Hanlon: 17:12 It hasn’t, but mostly because I just try not to talk to people.

Vicky Thompson: 17:16 I feel the same way at conferences, actually.

Shane Hanlon: 17:18 Yeah.

Vicky Thompson: 17:18 [inaudible 00:17:20].

Shane Hanlon: 17:20 This is my preferred medium, frankly.

Vicky Thompson: 17:21 Yeah.

Shane Hanlon: 17:22 I’m outgoing, but not.

Vicky Thompson: 17:23 Right. You’re an extroverted introvert.

Shane Hanlon: 17:26 I-

Vicky Thompson: 17:26 Well, that’s what I am.

Shane Hanlon: 17:27 Nope, that’s what I am. Yeah.

Vicky Thompson: 17:28 Yeah, yeah. Well anyway, given his success and awkward interactions, do you think he ever thinks about doing something different?

Gael Cascioli: 17:37 So I think I love higher education policy. I was quite a bit involved as much as I could back in Italy, and that’s a field that I really care about. That’s something that really needs to be, the whole system in Italy, for example, but I’m sure many other countries, needs to be reformed. And that’s something that I really strongly care about and have strong ideas about that.

Jason Rodriguez: 18:08 What drives those strong beliefs in education policy?

Gael Cascioli: 18:14 I think that I got so much from the university in general, both as a professional and as a person that… And I always been, since high school, involved in school politics somehow. So I saw that there is possibility for change. Even if it’s small, it’s very small, but there is always possibility for change. If you want to do something, you have a strong idea, you think that that way of teaching something or that way of evaluating students is not optimal, you can work with that. And I’ve got to know very, very good teachers along my career that were extremely involved in that. And sometimes, they had to sacrifice their research career to be in committees, to write down proposal for changing the order of the lessons or to propose new projects or new ideas for new courses and so on. And, I mean, their commitment for me was so… I don’t know. I don’t even know the word. It was so important to the community and so underrepresented to the outside.

19:27 Many other professors, they were just focused on research, research, and “Yeah, I have to teach, but just because I am forced to. It’s not my passion.” They tended to dismiss these other teachers because “Yeah, yeah. They’re just wasting their time. They like being important or whatever.” But actually, I’ve witnessed with my own eyes true change. And we as a committee of students went to those peoples and said, “This thing is not working at all.” And after talking for a few weeks, they understood our real struggle. And they actually worked so hard to change it, and it changed. And talking with the younger students the years after, they could really… I mean, they had this change, and something changed for them.

20:11 And I’ve come across many people that told me, “Oh, why are you doing this? Nothing will ever change. I mean, you’re not the minister of education or whatever.” There is always space to change. There’s always room to change. And I think it’s something, at least in the system where I come from, it’s mainly based on voluntary people, just people that love it, that have a strong passion for it and do it just for the sake of doing it. Because you’re not rewarded. You’re not paid. Sometimes, people hate you because you’re doing that, because you’re messing their routine. And so I think that’s something that really needs to be picked up, but it needs to be done by people that care about it, not people that do it because they get a salary out of it. So I’d love to do that.

Shane Hanlon: 20:56 This is just a powerful thought, and I was wondering if it influenced how he thinks about science now.

Gael Cascioli: 21:11 I would say that from a cultural standpoint, I think that in some work environments, too much focus is put on productivity. So sometimes you publish just… Publish or perish, right, that whole philosophy.

Jason Rodriguez: 21:29 Yeah.

Gael Cascioli: 21:33 And that has a lot to do… And this is why I come back to higher education, because in some countries, that’s the way of evaluating teachers, which is counterintuitive. You need to teach, right?

Jason Rodriguez: 21:44 Yeah.

Gael Cascioli: 21:44 So I should evaluate you on your teaching skills, not on your h-index or number of citations. So that’s something that I think if you don’t pay attention to that and if you don’t work in a work environment that doesn’t really care about that… And I must say, I mean, where I’m right now I feel that I’m not pressured at all about my numbers, but I know very well other work environments where the numbers define you, right?

Jason Rodriguez: 22:10 Yeah.

Gael Cascioli: 22:11 And so in that case, you end up… Instead of publishing one groundbreaking, amazing research that takes three or four years, you split it in several different little things. And it also doesn’t give you the time to do high-risk research, because that’s an issue. I want to do, let’s say, high-risk research. That means that if I get to the final goal that I was thinking, this will be really groundbreaking. But we need to account for the fact that maybe this funding for four years will be just lost because it is a high-risk research. And in some environment, this has been not favored because of productivity, right? Because universities get funded based on their productivity numbers. So of course, I also understand the head of a department saying, “You can’t spend four years on one paper,” because yeah, that’s good for science, but that’s not good for business. I mean, I understand that. It’s not the fault of the people that apply the rules. It’s the fault of the rules themselves.

Jason Rodriguez: 23:19 Yeah.

Gael Cascioli: 23:20 So this is why I strongly feel about a change in the overall philosophy of higher education and higher research.

Vicky Thompson: 23:39 So is this how you feel about academia?

Shane Hanlon: 23:42 As an independent individual not affiliated with any organization, 100% yes. My personal opinion, let’s say.

Vicky Thompson: 23:55 You were like, “This is not my legal advice. All of my tweets are my own.”

Shane Hanlon: 23:58 Yeah. That was that version. Yeah.

Vicky Thompson: 24:00 Yeah.

Shane Hanlon: 24:01 Put that in my… I was going to say Twitter profile. X profile. Whatever.

Vicky Thompson: 24:06 Oh, it’s not Twitter. Yeah.

Shane Hanlon: 24:07 But if you type in twitter.com, it takes you there. So.

Vicky Thompson: 24:10 Well, that’s just good business.

Shane Hanlon: 24:12 That is a good redirect. But seriously, he definitely does have a point. Yes, we want to get science out there, but we want to get good science out there.

Vicky Thompson: 24:20 Right.

Shane Hanlon: 24:20 And I think there’s definitely a balance there. And frankly, that’s probably a great place to end for us. So with that, that is all from Third Pod from the Sun.

Vicky Thompson: 24:31 Special thanks to Jason Rodriguez for conducting the interview and to NASA for sponsoring the series.

Shane Hanlon: 24:37 This episode was produced by me with audio engineering from Collin Warren and artwork by Karen Romano Young.

Vicky Thompson: 24:44 We’d love to hear your thoughts, so please rate and review us. And you can find new episodes on your favorite podcasting app or at thirdpodfromthesun.com.

Shane Hanlon: 24:51 Thanks all, and we’ll see you next week.

Vicky Thompson: 24:59 Uranus. I thought that was the way that someone said it when they didn’t want to say Uranus.

Shane Hanlon: 25:04 See? This is… Well, we’re going to find out.

Vicky Thompson: 25:06 Also, I feel like I was making so many faces while you were talking about realistic science fiction on Jupiter. Like, please. Come on.

Shane Hanlon: 25:17 Hold on. I’m looking up a YouTube video.

Vicky Thompson: 25:22 Uranus, Uranus.

Shane Hanlon: 25:26 On how to pronounce Uranus.