Invisible forces: Weathering the (academic space) storm

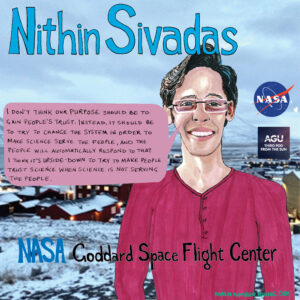

As a young child in India, Nithin Silvadas picked up Carl Sagan’s Cosmos, and it may have changed his life. From that moment on, he was enraptured with the universe. An undergraduate in engineering (where he literally helped build satellites) and PhD focused on radiation belts around planets (including Earth) later, he’s now a Research Scientist with NASA Goddard studying space weather.

As a young child in India, Nithin Silvadas picked up Carl Sagan’s Cosmos, and it may have changed his life. From that moment on, he was enraptured with the universe. An undergraduate in engineering (where he literally helped build satellites) and PhD focused on radiation belts around planets (including Earth) later, he’s now a Research Scientist with NASA Goddard studying space weather.

Wait, what’s space weather?

We talked with Nithin about plasma fields, how social class affects science, and who science really should serve.

This episode was produced by Shane M Hanlon, and mixed by Collin Warren. Artwork by Karen Romano Young. Interviews conducted by Jason Rodriguez.

Transcript

Shane Hanlon: 00:00 Hi, Vicky.

Vicky Thompson: 00:01 Hi, Shane.

Shane Hanlon: 00:03 What’s the most impressive thing you’ve built, like let’s say built by hand?

Vicky Thompson: 00:09 Oh, like from scratch?

Shane Hanlon: 00:12 I don’t know.

Vicky Thompson: 00:13 What is that even?

Shane Hanlon: 00:13 Take the prompt where you want to go.

Vicky Thompson: 00:15 Okay.

Shane Hanlon: 00:15 All right.

Vicky Thompson: 00:18 Thanks.

Shane Hanlon: 00:18 Choose your own adventure.

Vicky Thompson: 00:19 Choose your own adventure. Okay. Well, most recently, I’m not going to name the brand of basketball hoop because I don’t want to disparage a company, but Brian’s mom got Olivia a basketball hoop for her birthday, but we had to build it. It was the most insane adventure. It was terrible. The instructions were not clear, the pieces didn’t fit together. It’s one of those things that largely exists on tension, which is impossible to put together.

00:54 There was one point where we got part of it, two of the pipes stuck together, and then we realized they were on the wrong way. But then they wouldn’t come apart to the point where we built a mechanism and strung it between my car and my dad’s van and we’re trying to winch it apart. And then when that didn’t work, my dad was like, “Should we pull the cars in opposite directions?” I was like, well, as long as we’re not going to get mad when our windows break, when it snaps and our windows break, which didn’t happen, but it didn’t come apart either.

Shane Hanlon: 01:28 Oh my gosh.

Vicky Thompson: 01:28 We just ended up drilling new holes in the position that we had put the pipe, because we couldn’t get it apart. It was weeks of trauma. There was so much fighting, so much sweating, and just anger. It was terrible.

Shane Hanlon: 01:47 Did you get it built? Is there a final product?

Vicky Thompson: 01:49 It’s built. It’s built, and it’s one of those ones that you can adjust the height. It’s lovely.

Shane Hanlon: 01:53 Oh sure, yeah.

Vicky Thompson: 01:54 But I H-A-T-E it.

Shane Hanlon: 01:58 This is the worst IKEA experience anyone has ever had times 100.

Vicky Thompson: 02:03 Oh my gosh, yes. Because of all of the tension and you needed all these tools that they didn’t say you needed. We had to go to the hardware store multiple times. It was terrible.

Shane Hanlon: 02:13 I feel like it created figurative and literal tension for y’all.

Vicky Thompson: 02:20 Oh my gosh, yes, so much. But now it is built and now we will have wonderful afternoons of horse or whatever it is you do with basketball hoops.

Shane Hanlon: 02:31 You don’t even know what you do with basketball. Science is fascinating, but don’t just take my word for it. Join us as we hear stories from scientist or everyone. I’m Shane Hanlon.

Vicky Thompson: 02:31 And I’m Vicky Thompson.

Shane Hanlon: 02:51 And this is Third Pod from the Sun. Vicky, are you proud of your accomplishment at the end?

Vicky Thompson: 03:04 No, not really. Maybe. Maybe. I guess I should be. I guess Brian should be. I feel like he was the leader. I solved some key problems while we were doing it, so I guess I’m proud of that. I did some very intricate taping and chalking, like a little chalk line to make sure we got the new holes that we had to drill in the exact right spot. So yeah, I’m proud of that.

Shane Hanlon: 03:27 Okay. Well, no, that’s good. But not to rain on your parade or achievements, I think, immediately, that achievement, or frankly, anything, I could probably come up with for myself, might be put to shame by what our guest was building, or at least part of building in college.

Vicky Thompson: 03:50 In college? Did he build a computer?

Shane Hanlon: 03:51 Oh, I mean, maybe, but think bigger.

Vicky Thompson: 03:54 Oh, a car. I was in a class where I was going to have to be in charge of turning a car engine to a plant-based biodiesel thing, and I was so stressed out, I dropped the class. Did he build a car?

Shane Hanlon: 04:11 I feel like this says something about you that we don’t need to dig into. No, not a car. Think bigger.

Vicky Thompson: 04:20 No, I don’t have anything else.

Shane Hanlon: 04:22 Well, okay, I guess you don’t have to, so we’ll just get into the interview to figure out what’s going on. Our interviewer was Jason Rodriguez.

Nithin Sivadas: 04:29 I am Nithin Sivadas. I’m a research scientist affiliated with the Catholic University of America, and I work at NASA Goddard Space Flight Center. I broadly work in space weather. I’m in the Space Weather Lab. One way to explain what space weather is is basically outside our atmosphere, just outside at the edge of space, there is still gas. We don’t call it gas. They’re really, really high temperature gas, so it’s plasma. And that plasma and the electric and magnetic fields that the plasma exists in can affect spacecrafts, can affect human missions out into space.

05:33 We want to be able to know and predict and understand the weather of space around us. That is the broad project that I’m involved in right now. I grew up in India in a state called Kerala in the southwest coast. My parents were both engineers. When I was very young, my mom had this book called Cosmos by Carl Sagan. I was maybe 10 years old. I picked it up and I started reading. It really, really blew my mind. It just opened my mind. I was so fascinated by the universe.

06:20 Many kids are fascinated by the space, sky and the night sky, so I was also.But when you dig into the history of science and also just the depth of the universe, it captures your imagination. That is probably what always pushed me into the direction of science. My undergraduate was in engineering, and that was double validation from me that I liked science more and I like thinking more than necessarily building something specific.

Shane Hanlon: 07:08 What were you reading around age 10? Were you reading at age 10?

Vicky Thompson: 07:14 Yeah, I was always a reader. I think probably like The Baby-Sitters Club.

Shane Hanlon: 07:18 Oh, sure. What’s funny as you mentioned that, for me it was probably… My version of that was probably Goosebumps, honestly.

Vicky Thompson: 07:28 Yes, Goosebumps.

Shane Hanlon: 07:28 Yeah, Goosebumps were great. But I have this fairly vivid memory of my mom making, let’s say encouraging, love my mom, me to read Mutiny on the Bounty when I was probably around that age. I can picture it was framed or geared towards children as it’s very pretty cover. It was a little bit thicker, bigger print. I have no idea why. But yeah, I have this vivid memory of reading Mutiny into Bounty when I was young, some age.

Vicky Thompson: 08:00 That’s amazing.

Shane Hanlon: 08:03 Yeah, I have no idea why. I couldn’t honestly tell you. I know the main themes of Mutiny on the Bounty. I get it. It’s Mutiny into Bounty. I don’t know.

Vicky Thompson: 08:10 Just the gist of it.

Shane Hanlon: 08:14 Yeah, I don’t know why that was a thing, but honestly, it doesn’t really compare… I would say personally, that doesn’t compare to reading Cosmos at age 10. And if that wasn’t impressive enough, this is actually where the what’s the most impressive thing you’ve built prompt comes in.

Vicky Thompson: 08:14 Okay, let’s do it.

Nithin Sivadas: 08:38 In undergraduate, I got involved in building a student satellite. Many universities around the world, especially in India, during the time that I was beginning to do my undergraduate started working on university satellite development. That involvement in that project really… The satellite we were building was going to measure energy particles in space, and that’s what got me into plasma physics, particle physics, and then eventually space physics. I was like, okay, I want to study this.

09:16 My first PhD area of study was Auroral Physics. It was on how the northern lights and the southern lights were being formed and why they had the color they had and why did they move the way they moved. I had a particular project in mind and I was trying to work on that during my undergraduate, sorry, PhD program. Suddenly, I found something in the data that was very strange, and it was these really, really faint auroral signatures that nobody else had noticed before. We couldn’t immediately find an explanation for it.

09:58 That changed my whole project. I was trying to figure out what is this thing. It turned out, and I believe this to be the case and I’ve published a paper trying to provide evidence for this, that the earth has radiation belts around it. These are really high energy charge particles that surround the earth like a donut shape. This is dangerous for all spacecrafts and man missions that go through this. Now, this faint auroral arc is produced by energy particles at the boundary, the outer edge of this radiation belt, at least that’s my finding.

10:41 And that’s really cool because you have to go through the radiation belts to know where the radiation belts are at a particular point. It’s not static. It’s very dynamic. It grows and it swings. You want to know the extent of the radiation belt. But now if you can see it in aurora, that means you can see it using cameras, visible like optical cameras. You can image where the outer boundary of the radiation belt is and where it meets our atmosphere. That becomes really interesting and cool, but that changed my trajectory of my PhD program.

Vicky Thompson: 10:41 A satellite? Are you kidding?

Shane Hanlon: 11:32 No. No. Yeah, in college he was helping to build a satellite. I was probably building towers of solo cups if we’re being honest.

Vicky Thompson: 11:41 Houses of cards.

Shane Hanlon: 11:42 Literal houses of cards.

Vicky Thompson: 11:44 I can’t imagine what else he’s been working on.

Shane Hanlon: 11:47 Yeah. Actually shifting away from the hard research side of things, Nithin is really interested in how we think about science, specifically productivity in science. This kind of goes along with what Gael from last week was talking about the potentially flawed idea of publish or perish. Nithin is interested in the idea of “productivity” being a good measure or a measure of good science versus just getting a lot of papers out there. He actually wrote an article about it.

Nithin Sivadas: 12:20 The title was, Does the way we do science foster discovery? That was the question. The paper actually goes on to do a small toy model. There is a Monte Carlo model, and what it argues is that when we have a system that tries to maximize one parameter, so in science, in academia, we try to maximize certain things like the number of citations. The primary product of a scientist usually is a research paper that gets published in a journal. And that research paper will then be used by other scientists to do their research.

13:05 And then when they do that, they cite your work in their paper. The number of counts of those citations and the number of papers you publish, these are what usually mark how good of a scientist you are. When we have a system that maximizes this, the conclusion of my paper is that what you actually do is end up using the possibility of discovery instead of actually increasing it. The reason for this is actually fairly simple. If you think about it, if you do a new research that nobody else is working on, why would they care about the paper that you publish?

13:54 It would be so far away from their fields or their areas or their interests that they’re not going to cite your paper. But the thing is, you discover new things when you go astray. You have an infinite space. It’s like trying to find a lost shoe in a forest. You don’t know where that shoe is. You’ve got to do some random walks. You have to explore the area. But if you’re going to follow the other person who’s just walked in front of you, you reduce the chances of finding the shoe. This happens in science, is what I believe, and I feel like I’ve observed and I think we can make a case for this.

14:42 Things like this, which when I was young, I was very idealist might be the word, but like, oh yeah, discovery. You go out there and you can find things and it’d so beautiful and amazing. Everybody around you would love it when you go and do something that nobody else has done. But the opposite is true. If you go and do something that nobody else is doing, you will not get funding. You will not get research grants and citations, and people might not even understand what you’re talking about.

15:15 You have that pressure that goes in one direction. People with fewer papers and fewer citations who do work that is different from others who get fewer citations. There’ll be, again, a hierarchy. The people with the most power will call the shots, will decide what research should be funded into the future and what research should not be funded and so on.

Shane Hanlon: 15:51 I have a lot of thoughts on science as an institution coming from that institution, but perhaps I’ll just let Nithin’s very thoughtful words speak for themselves.

Vicky Thompson: 16:03 You don’t want to get in trouble.

Shane Hanlon: 16:05 I don’t want to get myself in trouble now.

Vicky Thompson: 16:06 We’ve highlighted all the great work Nithin has done, but it couldn’t have just been smooth sailing the entire time.

Jason Rodriguez: 16:14 When you think back on it, what has been one of the biggest obstacles for you to be where you are today?

Nithin Sivadas: 16:23 I was going to say immigration, but this question is interesting because where you are, there’s an assumption behind it. That’s what always interests me. This is clearly a ladder. It’s hard to climb the ladder, and I’m somewhere up in the ladder and what was difficult. Obviously climbing the ladder is difficult. You have to put this energy, you have to network with people. You have to have contacts. You have to develop certain ability to persuade others, have good certain writing skills.

17:08 There’s a mixture of these things you’ve got to do to climb this ladder. But I can tell you what are the things that actually affect, I think, the vast majority of people who don’t make it to these positions and who we usually never get to hear from. I think primarily that’s money, your class position in the society. If you look at me, I come from a small town in some part of India. I could talk about, oh, I come from this small town and I had no opportunities, blah, blah, blah, but it’s not true actually.

17:46 If you inspected closely, my parents were both engineers, and that would mean that in India, they would already become the top 10% of the economic population. And that would mean that I would have gotten a good opportunity to get education. In India, the public schools are very good, the top public schools, and they are very cheap. They definitely used to be very cheap. You didn’t need a lot of money to go to the top institutions in the country. That’s a big leg up. And then once you get to such positions and it becomes easier for you.

18:26 The doors open more easily for you. But instead, if you were somebody who were from a poor family, whether in India or whether in the United States, most doors are closed for you. I think that’s one of the biggest hurdles. But usually when we talk about these hurdles, people often focus on all the other things other than class. Usually it’s focused on identity, your sexuality, your gender. They do play a role. But to me, the evidence is in the demographics. How many people do you think are in NASA from the bottom 50% of the country in terms of class?

19:14 I’m sure it’s disproportionate. I don’t have the number, but simply based on my peer group, I can tell most people, the hardest thing, the thing that stops you, is money.

Shane Hanlon: 19:32 This I feel like is something we don’t talk enough, or maybe I’ll say I instead of we, but still, there are barriers in place for some that just don’t exist for others.

Vicky Thompson: 19:43 Oh yeah, 100%. We could talk forever on that. On the opposite end, some are affected by science in different ways or to different extents than others.

Nithin Sivadas: 19:55 I think the biggest challenge in the way we do science is that who science serves, who does science serve? I mean, this is the question I think we should all ask, especially when we claim to live in a democracy. I think what ends up happening because of the system that we talked about, the economic system, science ends up serving the people who own most of the resources.

20:28 When a company wants to market non-stick cookware, whether the chemicals from those non-stick cookware that fall into the ocean, cause cancer is not something that scientists are encouraged to or funded to delve into. When and if then they do, there are forces that push them out of doing that research. But instead, they would do the research on the non-stick cookware and how to make it marketable and make profit. So then it does not end up serving the people. It does not end up serving the demos.

21:14 I think that is our major problem. It does not serve the people. How can we make it serve the people is the question that we should answer. I say I don’t want to answer that question simply because I think a lot of people need to individually seek an answer to this question. My only advice is to politically educate yourself. Politics is not some field that is separate from us. In fact, it affects all of us, everyone, including chickens and cows. It affects every living being, because politics is the science of governing ourselves.

22:10 The only way is to educate ourselves politically, and that is the only way to make sure that all the things in our society, including science, and I think people have a good infusion to realize that the science is not serving the people. And that is why many people don’t trust scientists and science. I don’t think our purpose should be to try to gain people’s trust. Instead, it should be to try to change the system in order to make science serve the people. The people will automatically respond to that. I think it’s upside down to try to make people trust science when science is not serving the people.

Shane Hanlon: 23:10 A big part of why we do this podcast is to humanize science and scientists and hopefully instill trust in science. I think that’s a great point that science needs to serve the people if we’re trying to get people to trust science.

Vicky Thompson: 23:28 We really didn’t have to do much in this episode from a let’s provide commentary on what our guest said perspective.

Shane Hanlon: 23:35 No, no, we didn’t, but that’s not a bad thing and an indication of a great guest.

Vicky Thompson: 23:44 If we get great guests, then you’ll be out of a job.

Shane Hanlon: 23:49 Oh, no. I will always find something to talk about, and that’s literally for another day. With that, that is all from Third Pod from the Sun.

Vicky Thompson: 24:02 Special thanks to Jason Rodriguez for conducting the interview and to NASA for sponsoring the series.

Shane Hanlon: 24:08 This episode was produced by me with audio engineering from Collin Warren and artwork by Karen Romano Young.

Vicky Thompson: 24:15 We’d love to hear your thoughts, so please rate and review us. You can find new episodes on your favorite podcasting app or at thirdpodfromthesun.com.

Shane Hanlon: 24:23 Thanks, all, and we’ll see you next week. Yeah, this is just reminding me, one of the most impressive things that I didn’t quite realize how impressive it was at the time that my dad built… My dad was an electrician. He basically kind of built our house, so that’s very impressive. But one thing I didn’t appreciate was our basketball hoop. Our driveway was just this long narrow driveway with a turnaround in it.

24:56 Literally it was just like a half court basketball court kind of thing, so you could back out and turn around. He built a basketball hoop there. Everything except for the backboard and hoop, it was all wood and it stepped back probably six feet off the edge of the driveway. It was basically a giant, maybe eight by eight, and then it was all wooden. That thing lasted for… I mean, it was my brothers. It was through my brothers and then through me. That thing was probably there for 30 years.

25:35 I mean, he would update things here and there. It was one of the things we just had it growing up, but I never quite realized until I saw what you’re talking about, the metal ones, the modular ones, even ones that people would nail or cement in the ground. My dad was just like that. He’s like, “I could have a better way of doing this. It’s probably cheaper and easier and whatever else,” but it was just cool. I just never quite appreciated it until I was older how cool it was. I was like, good job, dad.

Vicky Thompson: 26:02 Good job, dad.

Shane Hanlon: 26:04 Good job, dad. Oh man. Okay, so let’s keep doing this.