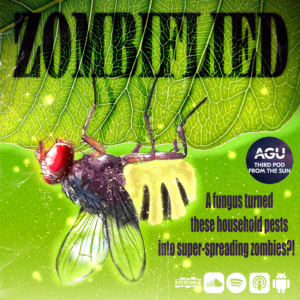

Tales from the (manus)crypt: Zombie-making fungi

Carolyn Elya is the Zombiologist in Chief, aka incoming Assistant Professor in Molecular and Cellular Biology at Harvard University. She’s been obsessed with parasites for a while, but it was the flies zombified by a fungus that made them climb, perch, and die that really caught her fancy. We talked with Carolyn about how fungi control flies and other insects, and the evolutionary implications for the zombie-making fungus and its doomed victims.

Biology at Harvard University. She’s been obsessed with parasites for a while, but it was the flies zombified by a fungus that made them climb, perch, and die that really caught her fancy. We talked with Carolyn about how fungi control flies and other insects, and the evolutionary implications for the zombie-making fungus and its doomed victims.

This episode was produced by Devin Reese and mixed by Collin Warren. Art by Jace Steiner.

Transcript

Shane:

Hi, Vicky.

Vicky:

Hi, Shane.

Shane:

What’s one time when you didn’t feel in control?

Vicky:

Oh, I have a list.

Shane:

A list? Oh, goodness.

Vicky:

I feel like I pass out more than the average person.

Shane:

Oh, we have touched on this before, but haven’t really…

Vicky:

Dove into it?

Shane:

… dove into it, yeah.

Vicky:

Yeah, so it’s like my fight or flight response.

Shane:

Oh, interesting.

Vicky:

I pass out.

Shane:

Just play dead?

Vicky:

Yeah. So, two times… or no, one time recently and one time in the past. So one time I was on the PATH Train and it was super, super crowded. It was St. Patrick’s Day in Hoboken, so it was that crowded.

Shane:

Oh, goodness. Okay.

Vicky:

I was coming back from somewhere in the morning, from staying at somebody’s house, and I suddenly got really hot and motion sick and everything all at once-

Shane:

Oh, no.

Vicky:

… and I knew I was going to pass out. I pass out enough that I know when it’s going to happen.

Shane:

Sure.

Vicky:

I just feel it happening. I just looked around for someone that looked trustworthy-

Shane:

Okay.

Vicky:

… or something, and went over to this person who I ultimately terrified and said, “I’m going to pass out. Can you just watch me? Just keep your eyes on me-”

Shane:

Okay.

Vicky:

“… keep me safe.”

Shane:

Yeah.

Vicky:

And I just sat down on the floor in front of them amongst all of these already inebriated young people-

Shane:

Oh, my goodness.

Vicky:

… in the PATH Train, and then came on the brink of passing out. And when I came back to, the person was clutching their purse, just looking at me

Shane:

Okay, I was like this person-

Vicky:

Because they had no context. What is going to happen next? She said, “I’m going to pass out. Keep your eyes on me.” I don’t know. I feel like I terrified this woman.

Shane:

Oh my goodness.

Vicky:

And then we didn’t speak any further about it. I just stayed sitting there. Yeah. And then my last Covid shot, I passed out on the floor in the CVS and they called the ambulance.

Shane:

Oh my gosh.

Vicky:

Yeah. I was just laying on the floor in CVS for a very long time.

Shane:

Did you warn… Well, I guess you couldn’t have known, but did they know that you had a history of just passing out?

Vicky:

No. So it doesn’t happen… It happens with the shots, but not every time. So I don’t mention it necessarily.

Shane:

You don’t want to make a thing of it, if it’s not a thing.

Vicky:

Oh, I also had a really, really bad reaction when I got some travel shots before I went to Thailand during the summer. That was really-

Shane:

This is so-

Vicky:

My blood pressure was-

Shane:

This is so much more content than I ever could have asked for.

Vicky:

Sorry.

Shane:

No, no, no, I don’t mean that in a bad way.

Vicky:

So yes, I do have times when I… The answer is yes. Let me just list all the times that I’ve laid on the floor in weird places.

Shane:

No, we’re…

I had a whole thing about…

Vicky:

Sorry.

Shane:

No, no, no. Again, sometimes I have things I actually want to get across, and then sometimes I don’t need to say the thing. Mine’s not super exciting. It’s just, one time when I was in grad school, I was driving with a friend somewhere, and I guess it was on a road that was black icy, but I didn’t know that… I think I’m a good driver. I think I recognize these things. It was in Memphis, and so I don’t know. It doesn’t really do that there, but we’re literally going around a cloverleaf and all of a sudden I realized that the back end of my car is tailing around me, and I look to my left and I can see the back end of my car as we are going in a circle, essentially. And it’s just one of those things where I haven’t really been in an accident per se, but I have spun out, I’ve tailed, I grew up in an area that gets snow and all of that.

Vicky:

Rural Pennsylvania.

Shane:

Rural Pennsylvania. And yeah, I saw the car coming around behind me and I looked at my friend and he’s just terrified. And I was like, we’ll see…

Vicky:

Where are we going to end up?

Shane:

We just did a couple loops and then stopped, still on this cloverleaf, facing backwards. So there were cars coming behind us. And so we just stopped, facing this other car, and I just kind of waved at him and did a three point turn and then got on the highway.

Vicky:

Okay. So I have to stop and just say, what’s a cloverleaf?

Shane:

No, an entrance to a highway or a road or something. Clover, like an on-ramp.

Vicky:

The loop?

Shane:

On-ramp.

Vicky:

Okay.

Shane:

Yeah. So, a cloverleaf-

Vicky:

Oh, okay. No, no, no. Okay, okay, okay. Okay. If you’re in the sky.

Shane:

Science is fascinating, but don’t just take my word for it. Join us as we hear stories from scientists for everyone. I’m Shane Hanlin.

Vicky:

And I’m Vicky Thompson.

Shane:

And this is Third Pod From The Sun.

All right, so we’re talking control today, not just to learn so much about you, Vicky. Really, I thought I knew so many things and it’s always such a wonderful discovery… Well, I won’t say wonderful. I’m glad you can laugh about you passing out everywhere, but it’s just… I also learned something new. But yeah, we’re talking about not being in control in this context because Halloween is coming.

Vicky:

Wait. I don’t… I thought… Okay, Halloween’s coming. So we’re talking about being out of control.

Shane:

Halloween is coming, so I’m starting to get that kind of creepy October feeling with the darkened tree limbs, the shortening of days, dead leaves underfoot. Halloween’s coming.

Vicky:

That just made me think of cemeteries. Creepy, spooky… So are we talking about zombies?

Shane:

We are talking about zombies, yeah, of course we are.

Vicky:

Okay. Did you see that there’s a new zombie movie out that’s fun for the whole family, called Zombie Town?

Shane:

Fun for the whole family? No. Legitimately, I missed this one, which is surprising because I watch a lot of movies and TV. No, but I’ve seen many, I guess, other zombie movies over the years and I don’t really know what it is about zombies. We’ve talked about this frankly already in this series. We seem to be obsessed with the undead, how they’re manipulated by some unseen force, how they are controlled, the beginning theme of this…

Vicky:

Okay. Yeah. There you go.

Shane:

Honestly, we’re just going to embrace it. And today we’re talking about zombies with Devin Reese.

Hi, Devin.

Devin Reese:

Hey, Shane.

Vicky:

All right, Devin, what are we talking about today?

Devin Reese:

My conversation with a zombiologist. It was a real eye-opener. Don’t worry, I am still alive. An incoming professor at Harvard in Organismic and Evolutionary Biology.

Vicky:

Zombiologist, I don’t think I’ve ever heard that before, or met one. Do I want to meet a zombiologist?

Devin Reese:

You do. Carolyn Elya tells incredible stories about how fungi take control of certain organisms.

Shane:

All right. So I’m glad that this is an audio interview and not in person. So let’s get into it.

Carolyn Elya:

My name is Dr. Carolyn Elya and I am currently a postdoc in the de Bivort Lab at Harvard in the Department of Organismic and Evolutionary Biology. But I’m starting my own group in January in the Department of Molecular and Cell Biology, also at Harvard.

Devin Reese:

Congratulations. And I noticed, in terms of starting your own group, that your new title might have something in it like Zombiologist in Chief, which I thought might be the best title I’ve heard. So let’s dig into that a little bit. In terms of your background, at what point in your life did you become interested in this?

Carolyn Elya:

So I guess, in terms of when did I become interested, as soon as I learned about this stuff. Who could not be interested in zombie-making organisms? So I guess just generally, these systems, once they came on my radar, they weren’t going to leave.

Devin Reese:

So it’s fair to say that maybe you need to tell us something about some experience you had with a zombie that meant that you could never leave this alone, but we’ll leave that for now. When you were a kid, could you have anticipated that you’d be studying these zombie-making organisms for your career?

Carolyn Elya:

I think if you would’ve told me as a kid that this is what I would wind up doing, I would have not believed you. First of all, I liked science as a kid, but I liked it less and less as I went higher and higher in my primary educations. And by the time I graduated from high school, I had pretty much decided I was probably done with science and that what I would be working on as an undergraduate would be more in the realm of the humanities. So I sort of went off to college thinking I would be a Spanish major. And then I got to college and found out that I had to take these general education requirements, one of which was chemistry. And I was really mad, but I signed up for it because I had to do it. And I walked into that lecture ready to hate chemistry, and the professor started talking and all of the things she said made a lot of sense and were actually super interesting. And so then I sort of got back on the science train.

Devin Reese:

I’m excited for you and for the field, that you found your way back to science despite that kind of experience because I think that this does happen a lot.

So then in college you realized that chemistry was exciting.

Carolyn Elya:

I think chemistry is so, so cool, but one of the things that I recognized or at the time was thinking is, chemistry is wonderful, but a lot of the problems in chemistry have been solved. And where chemical applications are being most heavily utilized nowadays is in the realm of medicine and biology. And so if I want to do something useful, then maybe I need to know biology as well. And so then I took a biology course, and so ultimately I wound up majoring in biochemistry and molecular biology.

Devin Reese:

Okay. And so then when did you first hear about these zombie-making relationships?

Carolyn Elya:

After I had graduated from college, I was listening to a podcast, which I still listen to, and they had an episode on different parasites. And one of the parasites they were talking about was actually a parasite that I was working with in the lab where I was a technician. And then when I went to grad school, I was interested in, just generally this idea that things that we cannot see, other organisms that are constantly around us are influencing the way that we behave. And so that falls in this space of behavior manipulation.

Devin Reese:

So were you thinking about it in terms of humans as well, at that time?

Carolyn Elya:

Yeah. So at the time, it was becoming very apparent that we’re constantly populated by millions of bacteria. So I think this really started with the revelations about the human microbiome, but then it sort of expanded to, well, every creature has a microbiome. There’s microbiome of the exterior of the animal, and the gut certainly is very usually populated. And so it seems that if there’s some way that these microbes that are associated with us and sort of rely on our actions for their fitness to change our actions, then there’s no reason why they wouldn’t evolve that ability.

Devin Reese:

Sounds a little creepy. Do you find it a little creepy?

Carolyn Elya:

I actually don’t. I think there’s so many things that influence our behavior, and microbes just trying to get by, power to them. If that’s what they need to do, and they figured out how to do it, I’m not going to stand in your way.

Devin Reese:

Well, I’m thinking that if you were actually working on human zombies, Harvard would not have hired you, right? You’d probably be in the clinker. So what will you be studying as a Zombiologist in Chief?

Carolyn Elya:

I’m going to be heading a group, and our main focus is going to be on understanding how the heck this little fungus that can’t think and has basically just been pushed around by evolution, has come to figure out how to manipulate fruit flies in these really complex and interesting ways in order to benefit its own fitness.

Devin Reese:

And so specifically, I know you have been working on fruit flies, correct? And the fungi. So when did that become the subject of your interest?

Carolyn Elya:

The first one of these systems I heard about was the zombie ant. So that was sort of like, “Oh my gosh, that’s so cool.” And when I learned that this also happens in flies, I actually couldn’t believe it. And I was actually doing an experiment for this gut microbe project that necessitated the collection of “wild” flies. I put wild in quotes just because these were flies from my backyard in Berkeley, so I’m not sure how wild they actually are, but flies from nature. And so I was basically trying to get flies to come to my backyard by enticing them with rotten fruit. And then I was grabbing them using glorified crazy straw aspirator and bringing them to the lab to grind them up and see what sort of bacteria they were carrying. And I was done with this experiment, but I didn’t really want to deal with my nasty gross pile of rotting fruit, and so I was actually out of town for a week and I came back and I was like, “Oh, I guess I need to deal with this now.” And I went and I started poking around in it and I actually noticed a bunch of dead flies.

And these flies were interesting, not because they were dead, but because they had their wings up and they had a bunch of crap on their backs. And the crap was in this sort of banded pattern. And because I was sort of interested in this realm of microbes that alter our behavior, I recognized that this was probably intermopthera muskie that had killed them, and so got really, really excited and basically decided that I needed to get this isolate into the lab so that I could start working with it.

Devin Reese:

This intermopthera, is that how you say it? This intermopthera muskie you mentioned. Is that a fungus, then?

Carolyn Elya:

That’s right.

Devin Reese:

When you saw the flies with this strange banding, you already had enough context that right away you’re like, “That’s this fungus.” Not just this fungus, but the particular species of fungus.

Carolyn Elya:

There’s a really sort of serendipitous path to why I was able to know that that was intermopthera muskie. Someone in my lab that was doing another project, that had come back from the field and one of their flies had mysteriously died and burst open with all of this white stuff, and they came into the lab with this dead fly and we’re like, “Oh my gosh, I don’t know what happened to my fly. It looks like it’s covered in crystals.” And my lab-mate said, “That’s intermopthera.” So I knew that it was out there, and to keep my eyes open for it.

Vicky:

So as a zombiologist who studies how fungi turn flies into zombies, I guess she’s probably always on the lookout.

Shane:

Yeah, there might be a different perspective on the world, expecting to see little fly zombies at every turn. Yeah. And I get really excited when I come across, I don’t know, a neat-looking frog. Carolyn gets excited when she comes across flies with white stuff spilling out of their bodies. It’s like return of the living dead, just with mold, I guess.

Devin Reese:

What did you do, Carolyn, after you found those creepy-looking flies?

Carolyn Elya:

I grabbed some of the dead flies the minute I realized what I had. I lived pretty close to lab. It was a weekend, but I ran to lab with my flies and I threw them under, just the dissecting microscope, to see if I could get a better look at the crap coming out of their back. And I could see that there were spores that had landed and the spores were long dead, but it looked… I was sort of gaining more and more confidence that this was intermopthera.

Devin Reese:

Did you literally physically run or did you drive?

Carolyn Elya:

I probably speed-walked. I don’t know if I ran ran, but I definitely hustled. It was, I was living five blocks away or something. Really convenient. So I scooted over there and the lab was empty, but I was there with my dish of dead flies… Or Tupperware, I guess I threw it in a Tupperware because I didn’t have any dishes at home. Yeah. And just checked him out.

Devin Reese:

When you get stopped, maybe you get a jaywalking ticket and you’re trying to explain to the officer, “But see, these dead flies, I need to get these to the lab because of this white stuff,” and they would think you were just nuts.

Carolyn Elya:

There’s many reasons to think that I’m nuts, but yeah, I can see that scenario playing out.

Devin Reese:

Tell me more about why these flies that you found on the rotting fruit had this white fungus exploding out of them. What had happened to these unfortunate individuals?

Carolyn Elya:

Yeah. So they are unlucky flies indeed, in that they had been infected by intermopthera and killed by intermopthera. So the way that intermopthera infects flies is by actively dispersing infectious propagules, which I’ll sometimes call kinedia, or sometimes called spores, into the environment. So one of these spores just has to land on the skin of a fly. The fly doesn’t have to eat the spore. The spore doesn’t have to land on a cut or an abrasion on the fly’s skin. It just lands on the skin and then it secretes this cocktail of enzymes that serve to effectively melt the surrounding cuticle and make it soft enough for the fungus to grow this sort of passageway that we call a germ tube that gets into the fly’s open circulatory system, which is called the haemocoel. And so it gets into the haemocoel, and we don’t know how this happens, but somehow it recognizes different tissue types and it only starts devouring one specific tissue type, which is the fat body. So in flies, the fat body is kind of analogous to the liver in vertebrates. It has an energy storage function and also has a little bit of an immune function. And so the fungus starts chomping down on this organ, which the flies don’t need to live. So this is sort of a sneaky strategy in eating this particular tissue.

Devin Reese:

So that’s pretty wild, what you just said. It sort of puts a fungus in a whole new light. So some of the things you mentioned… The fungus lands on the fly and essentially bores a hole through it. When you say the fungus eats, since they don’t have mouths, does that mean it’s just sort of soaking up nutrients from the fat body?

Carolyn Elya:

So we don’t know precisely, but my best guess is that the fungus is secreting metabolic enzymes to first basically kill the cells and then scavenge their insides. It’s also possible that fungal cells are engulfing the fat body, though we don’t have any evidence that that’s the case. So I think it more of just sort of like a barf on your food, kind of approach.

Devin Reese:

And then the fly survives even as its fat body gets all eaten up?

Carolyn Elya:

So the fungus eats this tissue. But then we also know that while these cells are initially chomping down on the fat body, as soon as two days after the fungus and the fly are introduced to each other, let’s say, the fungus winds up invading the fly’s nervous system. So the fungal cells are actually inside the fly’s brain and the fly’s ventral nerve cord. So the ventral nerve cord is sort of like the insect analog to the spinal cord. So it’s all up in the nervous system. And this is well before anything obviously wrong has started to happen behaviorally. So the fungus is in the nervous system and it’s in the body cavity and the fungus in the body cavity just continues to proliferate and proliferate and eat that fat body and just basically grow, exponentially. Eventually, the fungus runs out of fat body and so it then takes off the breaks and now it will eat the gut and the gonads.

And it does that as it’s preparing to leave the fly because it’s recognized that this fly is no longer useful. Food is run out. And so this is when all of the things that I’m really interested in, happen. So this fungus coordinates this extremely crafty exit strategy, which involves breaking down these internal organs, shifting morphology, so it puts on a cell wall because it’s getting ready to basically go back out into the very unforgiving world. And then it elicits a series of stereotyped behavior manipulations in the fly. And these behavior manipulations ultimately wind up positioning the fly, ideally, for the fungus to then burst out of the fly and spread its spores everywhere to get more flies sick.

Devin Reese:

So over a period of two days, then, the fungus is entering the fly, consuming its fat bodies, and then moving on to the rest of its body. But you mentioned the behavior modification. So what is the fly doing during this process?

Carolyn Elya:

So just remember that the fungus is already in the brain two days in, but we really don’t see a whole lot happening in terms of behavioral changes until the very end of the fly’s life. So, first the fungus makes the fly do what we call summiting behavior. So climbing something. Fancy word for climbing, and that’s sort of in the name, right? If you summit a mountain, you’ve climbed the mountain. So summit disease is just getting up high. And then when this happens, the fungus makes the fly do its second thing, which is to extend its mouth parts or proboscis. And so the proboscis gets extended and when it makes contact with the surface that the fly is standing on, there’s actually some glue, some gluey substance that comes out of the proboscis that serves to anchor the fly in place. And we don’t know what this glue is made of, and we don’t know who makes it, though I suspect it’s probably the fungus.

So now you have a fly that’s stuck up high, literally stuck up high, and the last thing that the fungus makes the fly do is to move its wings up and away from its back. So it lifts them up in this very uncanny, pretty rapid transition from flies normally having their wings sort of parallel to their body axis, flat across their back, to this sort of upward, very sort of conspicuous positioning. And then the flies die. And then after the flies die, the fungus grows out through the flies’ cuticle, and it forms these, usually bands of these spore launching structures called kinedia phores. And these bands actually tend to emerge underneath where the fly’s wings would’ve been, had they not been raised. And one of the creepiest, and one of my favorite things, about this system is that not only is this strategy sort of multifaceted and complex, but it also has a specific timing. So the fungus only kills the fly and it only makes the fly do these behaviors as the sun is going down. So there’s this really sort of weird clock element to this whole story.

Devin Reese:

So are you suggesting that a fungus then has some sensory capability, some circadian rhythm, some way to know what time of day it is?

Carolyn Elya:

Yes. And this is well known for many fungi. Across the tree of life, clocks are a thing. That’s important. Time of day is extremely important for survival. And so it makes a lot of sense why most organisms have mechanisms for detecting, “Oh, it’s morning. This is the time where I should be going out and gathering food,” or, “It’s evening. This is the time that I should be settling down,” if it’s a diurnal animal.

Devin Reese:

So even a fungus has a circadian clock. And when you said that might be… It’s sort of the optimal time, why would it be optimal for the fungus to induce this fly behavior at dusk?

Carolyn Elya:

So we think it’s optimal for the fungus to time these behaviors and the subsequent death of the animal and then eruption from the animal to line up so that basically the fungus is emerging at night because the fungus really likes it to be sort of cooler. So it does better in cooler temperatures. And it also needs high humidity in order to best germinate to actually sort of infect the next round of hosts.

Devin Reese:

So I do want to make sure we talk a little more about the mechanisms that you’ve studied. So I hear that the fungus makes it into the nervous system of the fly and causes it to do this weird summiting behavior and for the wings to go up. But once it gets to the nervous system, what is the fungus doing to cause that behavior? It sounds like a pretty sophisticated interaction.

Carolyn Elya:

Yeah. So there’s still a lot of things we don’t know about this mechanism, but I can tell you what I’ve learned so far. I picked summiting as the behavior to focus on, because you can imagine that there’s no sort of way that a fungus could just push on a muscle and make a fly summit. Summiting is a complex behavior. It involves knowing where you are in your environment, being able to differentiate up from down. All of these different things. Whereas putting your wings up is kind of a dumb behavior. You can imagine just pushing on a muscle and making a wing move. And similarly with proboscis extension. Proboscis extension could be driven by changes to neural activity, or it could just be, “Oh, man, I’m really bloated and I really need to just put my proboscis out, because it’s got nowhere to go, otherwise.” I was able to actually watch what happens when a fly is performing that summiting behavior, and what actually happens is that the fly starts to move like crazy. They become very, very active, whereas prior to summiting, they’re pretty lethargic, which makes sense because they’re very, very sick. But during summiting they have sort of this burst of activity and basically just stop moving afterwards. And so this burst of activity actually turns out to be the hallmark of summiting behavior.

Devin Reese:

And by this time, the fungus is in the brain of the fly, making it get really active?

Carolyn Elya:

I was able to run a screen in order to identify neural components within the fly that are important for this behavior. And so I’ve mapped out this little circuit that we think that the fungus is manipulating in order to drive this activity in the fly.

Devin Reese:

And how can you possibly, with this organism the size that a fly is, be talking to me about figuring out which part of their neural circuitry is being manipulated by the fungus?

Carolyn Elya:

So this is because there have been thousands, probably more like tens or hundreds of thousands of scientists that have worked on fruit flies and that have contributed to developing tools that we can use in the fly to access particular cell types, including just handfuls of neurons, and to manipulate those cell types in very specific ways. So I can basically go to a website and I can look up a list of all of the flies that are available that people have generated, and I can basically shop for flies and have these flies delivered to me. I call this Fly Amazon. And so the flies come and I can use these flies for my experiments. And so I can take a fly that I know basically will allow me to have access to a particular subset of neurons, and I can combine those flies, basically mate those flies, to another fly that has an effector that will kill those neurons, silence those neurons, activate those neurons. And so you have this really exquisite control over the manipulations that you can make in flies.

So even though they’re extremely tiny, we have all of these combinations of things that we can do with them because of all of the work that people have put into the system.

Devin Reese:

And that allows you to really target down to, literally groups of nerve cells. And so what have you found about what parts of the brain are being impacted by the fungus?

Carolyn Elya:

The circuit involves, we think some neurons within the fly’s circadian system, some neurons within the fly’s neurosecretory system, and then a particular neural hemal organ called the corporalata, which produces a hormone called juvenile hormone. And despite its name, juvenile hormone, it actually does a lot more than just sort of maintain juvenile identity in insects, to the point where we don’t totally understand everything that juvenile hormone does. But we think that basically the fungus triggers the circuitry to release juvenile hormone and that this is driving this increase in locomotion.

Devin Reese:

So the fungus is really taking advantage of the fly’s existing time-adapted system to make this behavior change. Because you’re talking about the fly’s neurosecretory cells so those are neurons that are secreting chemicals which can then have an effect elsewhere in the fly’s brain and then drive the behavior.

Carolyn Elya:

Yeah, that’s right. Sort of just thinking from first principles, if you are a fungus, what is the easiest way in order to change the behavior of a host? And the easiest way is use what the host already has, against it. It’s not to make something from scratch, it’s to just turn something on at an inappropriate time that winds up favoring your own fitness.

Devin Reese:

So aren’t there certain advantages to a parasitic organism not killing its host, and yet in this case it clearly does kill its host?

Carolyn Elya:

Yeah, absolutely. So I don’t think that emuskie is an ideal parasite at all. I think that it’s sort of cobbled together a way of life that works well enough, but man, it needs a lot of things to go right in order to succeed. So like you said, killing your hosts, not a great idea. Then you have to find another one. You’re just creating problems for yourself. The fact that it has this particular timing, it requires a host to be present at the time when it’s actively spreading. The spores that are launched can’t survive for very long after they’re launched. If they don’t land on a host, they’re basically just going to dry up and die. So all of these things mean that really, it’s kind of a diva fungus, in a way, in that it needs a lot of very specific things to happen in order for it to succeed. So I don’t think it’s an example of the ideal parasite, for sure.

Shane:

So, ideal parasite is not two words that I… Well, I guess most folks would typically combine. I like disease ecology stuff, I think it’s fascinating, but yeah, for most part, I feel like that’s not super common. But I guess by not killing your host, you would ensure that there are more hosts available in the long run.

Devin Reese:

True. True. But I think these parasite-host relationships are continually evolving, right, Shane? It’s not static. Because each one must adapt to get a survival leg up on the other.

Vicky:

Yeah, and it’s hard to imagine how the relationship between this fungus and fruit flies evolved when it’s really just so bad for the fruit fly who gets nothing out of the arrangement.

Carolyn Elya:

I think we need to know more about the ecology of the fungus in order to understand how the fungus and the flies are influencing each other’s evolution. I think one of the things that I’ve heard about and I’ve seen with this fungus is again, the hallmark of a really bad parasite. What it tends to do is it tends to take down local populations of flies. So you can imagine if it murders everyone, then there’s no way that you can actually learn from that and evolve resistance to it. The relationship between the fly and the fungus has been going on for a very, very long time. So we imagine probably at least tens of millions of years, more likely hundreds of millions of years. So there’s been a lot of time for the fungus to proverbially figure out how to sort of get all of these different things to go.

Devin Reese:

Do you specifically mean this species of fungus and fruit flies, when you say the relationship has been going on for a long time?

Carolyn Elya:

We know that certainly between emuskie and flies, that this relationship is very longstanding, but it’s presently not totally clear what we’re dealing with. When we say emuskie and a house fly or emuskie and a fruit fly. It seems very likely, given the genetic data that we’re capturing now, that what we’re talking about are actually pretty distinct lineages of emuskie. So we could be talking about different species when we’re talking about emuskie that infects fruit flies versus emuskie that infects house flies.

Devin Reese:

Are there other fungi that infect other insects and cause similar types of zombie-like behavior?

Carolyn Elya:

There are. So I mentioned the zombie ant, which was sort of my foray into this area. So this is caused by a fungus called of ophiocordyceps. And in the case of ophiocordyceps, there’s actually a bunch of different species of ophiocordyceps, and each species is thought to infect a different host species of ant. And we might very well wind up finding something similar with intermopthera but we don’t have the level of resolution that exists for ophiocordyceps taxonomy. What’s really cool about ophiocordyceps is that it is about as distantly related as we are from fruit flies, to intermopthera, and yet it causes very similar behavioral changes in the ants. So similarly, the ants wander, climb up somewhere, and they don’t have probosces, they have little jaws, they bite down and they have lock jaw, so they wind up being basically, again, fixed in place. And then after they die, the fungus sprouts out of their head, forming this fruiting body, which basically looks like a mushroom, that sporulates and gets all of their little ant friends sick.

Devin Reese:

And so are there also non-fungi, like other types of pathogens, that cause organisms to act like zombies? Or is this really a fungi thing?

Carolyn Elya:

There’s a bunch of different cool examples out there. So some of my favorites, there are these worms that infect crickets and grasshoppers and make them jump into bodies of water because the worms themselves need to be in water to sort of complete their life cycle. And the consequences for the crickets can be the cricket drowns because it basically flings itself into water. Sometimes the crickets make it out okay, but most of the time it’s not a super happy story for them. There are wasps. There are so many wasps that do really interesting things. My favorite wasp is the jewel wasp, which, this is super crazy, it needs to feed its babies, as we all do, and so it uses a cockroach for that. And so what it does is it finds a cockroach and it stings the cockroach, just anywhere, at first to sort of stun the cockroach.

And while the cockroach is kind of like, “Whoa, what’s going on,” the jewel wasp then gives it a second sting. This one, it’s able to target very precisely into a particular region of its brain in order to effectively make the cockroach its willing slave. So it does this and the cockroach no longer seems to have any sort of sense of self-preservation because then the wasp will walk it back to its little nest and it will lay its babies on the cockroach and seal the whole thing in like some twisted Edgar Allen Poe story. And then the babies will eat the cockroach and then become adults themselves, and the whole thing begins again.

Devin Reese:

So these really gruesome tales, again, seem to be really in insects and invertebrates more than in vertebrates. And yet of course, we have seen plenty of shows and movies about zombies. Are there any concerns about taking this fungus home? Could it ever act on a vertebrate brain?

Carolyn Elya:

Well, the short answer is no. I think I’ve been working with, and I’ve surely inhaled spores during my time working with the fungus, and I am not glued to the ceiling by my tongue. So I think that’s a good indication that this is not efficacious against vertebrates. But even in the absence of knowing that, I’ve been fine working with this. There’s so many reasons why this fungus would fail to infect a vertebrate. Our skin is different. That’s how they get in, right? Fly skin, human skin, completely different. You need different enzymes in order to access the insides of a human. Humans are hot, flies aren’t. Fungus doesn’t like hot temperatures. I told you that one of the reasons we think that the fungus times the course of events the way it does is because it likes it cool. And it’s not going to find that inside of a human host. And then of course, we have amazing immune systems. We have the ability to adapt to new antigens that are presented, whereas flies don’t have this ability. They don’t have antibodies. They have an innate immune system but you can imagine that this is a lot less flexible and potentially efficacious.

Devin Reese:

So you’ve seen the show, The Last of Us, or episodes of it?

Carolyn Elya:

I have, and I’ll say I was not going to watch it because there’s enough sadness in our world that I didn’t think I needed to watch something that was that much of a bummer. However, I was interviewing for jobs and everyone was asking me about it. And so it seemed pretty apparent that I needed to have something intelligible to say about it. And so I turned to my spouse and I said, “I think I need to watch this for work. Will you watch it with me?” And so we watched it.

We use the term zombies mostly because it’s a thing that people already sort of have scaffolding for in their brain. They know what we mean by zombies. But here, these flies are not undead. They are definitely dead and they’re not moving after they die. But their behavior has been changed in a way that they’re no longer acting sort of on their own, out of their own interests. They’re acting out of the fungus interests.

Devin Reese:

Now that you’re doing this work with this particular fungi, you’re not finding yourself climbing more mountains, hanging out on the summits or anything? I’m just checking.

Carolyn Elya:

No, the biggest way that my behavior has changed is just to take care of the fungus. And so maybe someone could argue that that’s a behavior modification in and of itself, that I’m propagating this organism that I didn’t have any interactions with, prior to.

Shane:

Vicky, so next time I do something that annoys you or makes you angry, which, I don’t know, might be five seconds from now, I’m just going to-

Vicky:

Right now.

Shane:

Right this very second. I’m just going to blame it on a fungus that’s controlling me.

Vicky:

Okay. So does that mean you’ll be climbing on top of tall things, buildings, for no reason? I’ll just watch out for that.

Shane:

Well, I am going on a hiking trip this weekend and we’ll be on the top of some mountains, but I am so risk-adverse that I imagine even a zombie version of me would be afraid of putting myself out there like that, let’s say.

Vicky:

Okay. I don’t know if imagining you as a zombie is a good thing to do, but I think I’m going to be thinking a lot about that from now on.

Shane:

Oh. From now on.

Vicky:

Yeah.

Shane:

Through spooky season and beyond…

Vicky:

Just always.

Shane:

… it’s just zombie Shane. Maybe I now have a… I was going to say I have now a Halloween costume, but I would like to see you go as me being zombie Shane for Halloween.

Vicky:

That’s really deep.

Shane:

It is really deep. Yeah. Good luck with the meta angle with that. And so with that, we’ll stop there. And that is all from Third Pod from The Sun.

Vicky:

Thanks so much to Devin for bringing us this story and to Carolyn for sharing her work with us.

Shane:

This episode was produced by Devin with audio engineering from Colin Warren, and artwork by Jay Steiner.

Vicky:

We’d love to hear your thoughts on the podcast. So please rate and review us, and you can find new episodes on your favorite podcasting app or at thirdpodfromthesun.com.

Shane:

Thanks all, and we’ll see you next week.

Vicky:

Have you ever passed out?

Shane:

No, but I’ve gotten close a couple of times, yeah. No, not to my knowledge.

Vicky:

I’m trying to think. I passed out in the nurse’s office in high school. I passed out in countless doctors’ offices. I passed out on the floor of CVS, on the floor of Claire’s…

Shane:

Oh, that’s fun.

Vicky:

… getting my ears pierced. On the boardwalk in New Jersey. On the PATH Train. In the bathroom.

Shane:

This is like the worst of the greatest hits.

Vicky:

Yeah. In the travel doctor’s office, as I said. Maybe a plane, or almost on a plane. Anyway.

Shane:

All right. Well, I love this for you.